Alassane Ouattara

Alassane Dramane Ouattara (French pronunciation: [alasan wataʁa] (![]() listen); born 1 January 1942) is an Ivorian politician who has been President of Ivory Coast (Côte d'Ivoire) since 2010. An economist by profession, Ouattara worked for the International Monetary Fund (IMF)[1] and the Central Bank of West African States (French: Banque Centrale des Etats de l'Afrique de l'Ouest, BCEAO), and he was the Prime Minister of Côte d'Ivoire from November 1990 to December 1993, appointed to that post by President Félix Houphouët-Boigny.[2][3][4][5] Ouattara became the President of the Rally of the Republicans (RDR), an Ivorian political party, in 1999.

listen); born 1 January 1942) is an Ivorian politician who has been President of Ivory Coast (Côte d'Ivoire) since 2010. An economist by profession, Ouattara worked for the International Monetary Fund (IMF)[1] and the Central Bank of West African States (French: Banque Centrale des Etats de l'Afrique de l'Ouest, BCEAO), and he was the Prime Minister of Côte d'Ivoire from November 1990 to December 1993, appointed to that post by President Félix Houphouët-Boigny.[2][3][4][5] Ouattara became the President of the Rally of the Republicans (RDR), an Ivorian political party, in 1999.

Alassane Ouattara | |

|---|---|

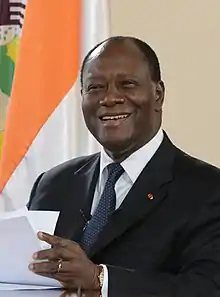

Alassane Ouattara in 2017 | |

| President of the Ivory Coast | |

| Assumed office 4 December 2010 | |

| Prime Minister | Guillaume Soro Jeannot Ahoussou-Kouadio Daniel Kablan Duncan Amadou Gon Coulibaly Hamed Bakayoko |

| Vice President | Daniel Kablan Duncan |

| Preceded by | Laurent Gbagbo |

| Prime Minister of the Ivory Coast | |

| In office 7 November 1990 – 9 December 1993 | |

| President | Félix Houphouët-Boigny |

| Preceded by | Félix Houphouët-Boigny |

| Succeeded by | Daniel Kablan Duncan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1 January 1942 Dimbokro, French West Africa (present-day Côte d'Ivoire) |

| Political party | Democratic Party (Before 1994) Rally of the Republicans (1994–present) |

| Spouse(s) | Dominique Nouvian (1991–present) |

| Alma mater | Drexel University University of Pennsylvania |

| Website | Official Presidential website |

| |

Early life

Ouattara was born on 1 January 1942[2][3] in Dimbokro in French West Africa.[6] He is a descendant on his father's side of the Muslim rulers of Burkina Faso, then part of the Kong Empire—also known as the Wattara (Ouattarra) Empire. Ouattara is of Muslim background[7] and is a member of the Dyula people.[8] He received a Bachelor of Science degree in 1965 from the Drexel Institute of Technology (now Drexel University), in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[2] Ouattara then obtained both his master's degree in economics in 1967 and a PhD in economics in 1972 from the University of Pennsylvania.[2]

In 1991, Ouattara married Dominique Nouvian, a French Catholic businesswoman of Jewish descent.[9] Their wedding was held in the town hall of the 16th arrondissement of Paris.

Career at financial institutions

He was an economist for the International Monetary Fund in Washington, D.C.[3] from 1968 to 1973, and afterwards he was the Chargé de Mission in Paris of the Banque Centrale des Etats de l’Afrique de l’Ouest (West African Central Bank) from 1973 to 1975.[2][3] With the BCEAO, he was then Special Advisor to the Governor and Director of Research from February 1975 to December 1982 and Vice Governor from January 1983 to October 1984. From November 1984 to October 1988 he was Director of the African Department at the IMF, and in May 1987 he additionally became Counsellor to the Managing Director at the IMF.[3] On 28 October 1988 he was appointed as Governor of the BCEAO, and he was sworn in on 22 December 1988.[10] Ouattara has a reputation as a hard worker, keen on transparency and good governance.[1]

Political career

Prime Minister

In April 1990, the IMF under the Structural Adjustment Program forced the Ivorian President, Félix Houphouët-Boigny, to accept Ouattara as Chairman of the Inter-ministerial Committee for Coordination of the Stabilization and Economic Recovery Programme of Côte d'Ivoire. While holding that position, Ouattara also remained in his post as BCEAO Governor. He subsequently became Prime Minister of Côte d'Ivoire on 7 November 1990, still under the IMF imposition,[3][10] after which Charles Konan Banny replaced him as Interim BCEAO Governor.[10] He also held the position of Minister of Economy and Finance from October 1990 to November 1993.[11]

While serving as Prime Minister, Ouattara also tried, illegally and against the constitution, to carry out presidential duties for a total of 18 months, including the period from March to December 1993, when Houphouët-Boigny was ill.[12] Houphouët-Boigny died on 7 December 1993, and Ouattara announced his death to the nation, saying that "Côte d'Ivoire is orphaned".[13][14] A brief power struggle ensued between Ouattara and Henri Konan Bédié, the President of the National Assembly, over the presidential succession in total disregard for the constitution that clearly gave Bedié the legal right to lead the country if Houphouet became unfit. Bédié prevailed and Ouattara resigned as Prime Minister on 9 December.[15] Ouattara then returned to the IMF as Deputy Managing Director, holding that post from 1 July 1994,[2][3] to 31 July 1999.[3]

1995 election

Prior to the October 1995 presidential election, the National Assembly of Côte d'Ivoire approved an electoral code that barred candidates if either of their parents were of a foreign nationality and if they had not lived in Côte d'Ivoire for the preceding five years. It was widely thought these provisions were aimed at Ouattara. Owing to his duties with the IMF, he had not resided in the country since 1990. Also, his father was rumoured to have been born in Burkina Faso. The Rally of the Republicans (RDR), an opposition party formed as a split from the ruling Democratic Party of Côte d'Ivoire (PDCI) in 1994, sought for Ouattara to be its presidential candidate. In late June 1995, RDR Secretary-General Djéni Kobina met with Ouattara, at which time, according to Kobina, Ouattara said: "I'm ready to join you."[16] The party nominated Ouattara as its presidential candidate on 3 July 1995[17] at its first ordinary congress.[18] The government would not change the electoral code, however,[16] and Ouattara declined the nomination.[19][20] The RDR boycotted the election, along with the Ivorian Popular Front (FPI) of Laurent Gbagbo, leaving the PDCI's candidate, incumbent president Henri Konan Bédié, to win an easy victory.[16]

President of the RDR

While serving as Deputy Managing Director at the IMF, in March 1998 Ouattara expressed his intention to return to Côte d'Ivoire and take part in politics again.[21] After leaving the IMF in July 1999, he was elected President of the RDR on 1 August 1999 at an extraordinary congress of the party,[22] as well as being chosen as its candidate for the next presidential election.[23] He said he was eligible to stand in the election, pointing to documents he said demonstrated that he and his parents were of Ivorian birth.

He was accused of forging these papers, however, and an investigation was begun.[24][25] President Bédié described Ouattara as a Burkinabé and said that Houphouët-Boigny "wanted Alassane Ouattara to concern himself only with the economy".[26] Ouattara's nationality certificate, issued in late September 1999,[27] was annulled by a court on 27 October.[27][28] An arrest warrant for Ouattara was issued on 29 November, although he was out of the country at the time; he nevertheless said that he would return by late December.[29]

On 24 December, the military seized power, ousting Bédié. Ouattara returned to Côte d'Ivoire after three months in France on 29 December, hailing Bédié's ouster as "not a coup d'état", but "a revolution supported by all the Ivorian people".[30][31]

A new constitution, approved by referendum in July 2000, controversially barred presidential candidates unless both of their parents were Ivorian,[32] and Ouattara was disqualified from the 2000 presidential election.[33] The issues surrounding this were major factors in the First Ivorian Civil War, which broke out in 2002.

When asked in an interview about Ouattara's nationality, Burkinabé President Blaise Compaoré responded, "For us things are simple: he does not come from Burkina Faso, neither by birth, marriage, or naturalization. This man has been Prime Minister of Côte d'Ivoire."

President Gbagbo affirmed on 6 August 2007 that Ouattara could stand in the next Ivorian presidential election.[34] Ouattara was designated as the RDR's presidential candidate at its Second Ordinary Congress on 1–3 February 2008; he was also re-elected as President of the RDR for another five years. At the congress, he invited the former rebel New Forces, from whom he had previously distanced himself, to team up with the RDR for the election.[35]

At the time, Ouattara said publicly that he did not believe Gbagbo would organize transparent and fair elections.[36]

The RDR and the PDCI are both members of the Rally of Houphouëtistes, and while Ouattara and Bédié ran separately in the first round, each agreed to support the other if only one of them made it into a potential second round.[35]

2010 presidential election and aftermath

The presidential elections that should have been organized in 2005 were postponed until November 2010. The preliminary results announced independently by the president of the Electoral Commission from the headquarters of Ouattara due to concern about fraud in that commission. They showed a loss for Gbagbo in favour of former prime minister Alassane Ouattara.[37]

The ruling FPI contested the results before the Constitutional Council, charging massive fraud in the northern departments controlled by the rebels of the New Forces. These charges were contradicted by United Nations observers (unlike African Union observers). The report of the results led to severe tension and violent incidents. The Constitutional Council, which consisted of Gbagbo supporters, declared the results of seven northern departments unlawful and that Gbagbo had won the elections with 51% of the vote – instead of Ouattara winning with 54%, as reported by the Electoral Commission.[37] After the inauguration of Gbagbo, Ouattara—who was recognized as the winner by most countries and the United Nations—organized an alternative inauguration. These events raised fears of a resurgence of the civil war; thousands of refugees fled the country.[37]

The African Union sent Thabo Mbeki, former President of South Africa, to mediate the conflict. The United Nations Security Council adopted a resolution recognising Alassane Ouattara as winner of the elections, based on the position of the Economic Community of West African States, which suspended Ivory Coast from all its decision-making bodies[38] while the African Union also suspended the country's membership.[39]

In 2010, a colonel of the Ivory Coast armed forces, Nguessan Yao, was arrested in New York in a year-long U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement operation charged with procuring and illegal export of weapons and munitions: 4,000 9 mm handguns, 200,000 rounds of ammunition, and 50,000 tear-gas grenades, in violation of a UN embargo.[40] Several other Ivory Coast officers were released because they had diplomatic passports. His accomplice, Michael Barry Shor, an international trader, was located in Virginia.[41][42]

The 2010 presidential election led to the 2010–2011 Ivorian crisis and the Second Ivorian Civil War. International organizations reported numerous human-rights violations by both sides. In the city of Duékoué, hundreds of people were killed. In nearby Bloléquin, dozens were killed.[43] UN and French forces took military action against Gbagbo.[44] Gbagbo was taken into custody after a raid into his residence on 11 April 2011. The country was severely damaged by the war, and observers say it will be a challenge for Ouattara to rebuild the economy and reunite Ivorians.[45]

The developments in the country were welcomed by world leaders. U.S. President Barack Obama applauded news of the developments in Côte d'Ivoire and CNN quoted U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton as saying Gbagbo's capture "sends a strong signal to dictators and tyrants.... They may not disregard the voice of their own people".[46]

2012 marriage law row

In a controversial move in November 2012, President Ouattara sacked his government in a row over a new marriage law that would make wives joint heads of the household. His own party supported the changes but the elements of the ruling coalition resisted, with the strongest opposition coming from the Democratic Party of Côte d'Ivoire.[47]

Second term, 2015–2020

Alassan Ouattara won a second five-year term in 2015 with almost 84% of the vote. With 2,118,229 votes, or 83.66% of votes cast, and a 54.63% turnout, Ouattara's victory was a landslide compared to the 50% required to avoid a run-off and the 9% of his closest rival, FPI leader Pascal Affi N'Guessan.

At the RDR's Third Ordinary Congress on 9–10 September 2017, it was expected that Ouattara would be elected as President of the RDR, but he instead proposed Henriette Diabaté for the post, and she was duly elected by acclamation.[48]

In March 2020, Ouattara announced to not run again at the presidential elections on 31 October 2020.,[49] and pushed forward the candidacy of Prime Minister Amadou Gon Coulibaly as the presidential candidate of the RDR. After the sudden death of Coulibaly on 8 August 2020, Ouattara considered putting forward Defense Minister Hamed Bakayoko, before renouncing due to alleged links to drug trafficking. In july, he announced to run for a third time in office. His candidacy was controversial as the Ivorian constitution only allow two terms. While the Constitutional Court ruled that the first one under a different constitution didn't count for the two term rule of the current one, allowing Ouattara to become candidate, it led to partially violent protests in Abidjan and throughout the country.[50] The election of October 2020 was thus boycotted by a large part of the opposition, and saw the reelection of Alassane Ouattara with 95.31% of the votes under a 53.90% turnout.

Honours

National honours

Ivory Coast:

Ivory Coast:

Grand Collar of the National Order of the Ivory Coast (4 December 2010)

Grand Collar of the National Order of the Ivory Coast (4 December 2010)

Foreign honours

Mali:

Mali:

Grand Cross of the National Order of Mali (3 September 2013)

Grand Cross of the National Order of Mali (3 September 2013)

Portugal:

Portugal:

Grand Collar of the Order of Prince Henry (12 September 2017)

Grand Collar of the Order of Prince Henry (12 September 2017)

References

- "Ivory Coast's Alassane Ouattara in profile", BBC News Online, 11 April 2011.

- "Profile at IMF website". Archived from the original on 21 December 2005. Retrieved 2011-04-11.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), 12 December 2005.

- CV at Ouattara's website Archived 9 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine (in French).

- "A tale of 2 presidents". CBC News. 25 March 2011.

- "Gbagbo: Preventing ECOWAS military misadventure in Cote d'Ivoire". Archived from the original on 8 July 2011.

- Laing, Aislinn, "Ivory Coast: Alassane Ouattara profile", The Telegraph, 6 April 2011.

- "Côte d'Ivoire's new president - The king of Kong - Alassane Ouattara takes charge but can he keep the peace?" He studied at the High School Zinda Kaboré in Ouaga (Burkina Faso) The Economist, 20 April 2011.

- Oved, Marco Chown (28 November 2010). "How ethnicity colors the Ivory Coast election". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- Smith, David (15 April 2011). "Alassane Ouattara reaches summit but has more mountains to climb". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "Basic texts and milestones" Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, bceao.int.

- "Historique". finances.gouv.ci.

- "Houphouët-Boigny et ADO: du comité interministériel à la Primature", ado.ci (in French).

- "Décès du Président Félix Houphouët-Boigny", ado.ci (in French).

- "African Leader Dies", Newsday, 8 December 1993.

- "Prime minister decides to quit", Associated Press (San Antonio Express-News), 10 December 1993.

- Mundt, Robert J. (1997). "Côte d'Ivoire: Continuity and Change in a Semi-Democracy". In Clark, John Frank; Gardinier, David E. (eds.). Political Reform in Francophone Africa. Boulder: Westview Press. pp. 194–197. ISBN 0-8133-2785-7.

- "Jul 1995 - Selection of Ouattara as RDR presidential candidate", Keesing's Record of World Events, Volume 41, July 1995 Cote d'Ivoire, p. 40630.

- Brahima, Coulibaly, "Côte d'Ivoire: Organisation du 2ème congrès ordinaire du Rdr, des cadres manoeuvrent pour le report", Nord-Sud (allAfrica.com), 27 July 2007 (in French).

- "ADO est élu Président du RDR, le 1er Août 1999", ado.ci (in French).

- "Oct 1995 - Presidential elections", Keesing's Record of World Events, Volume 41, October 1995 Cote d'Ivoire, p. 40759.

- "Ivorian ex-premier to quit IMF for return to politics", BBC News Online, 30 March 1998.

- Biography at Ouattara's website (in French).

- "Ivorian opposition elects former premier as presidential candidate", Associated Press, 1 August 1999.

- "Côte d'Ivoire: Police arrest scores outside politician's home", IRIN, 15 September 1999.

- "Ivory Coast opposition leader under investigation", BBC News Online, 22 September 1999.

- "Côte d'Ivoire: Former political foes strike pact to oust Gbagbo", IRIN, 18 May 2005.

- "Cote d'Ivoire: Court annuls presidential candidate's nationality certificate", AFP, 27 October 1999.

- "Opposition leader blasts 'undemocratic' government", BBC News Online, 29 October 1999.

- "Côte d'Ivoire: Arrest warrant issued for opposition politician", IRIN, 9 December 1999.

- "Ivory Coast coup a 'popular revolution'", BBC News Online, 29 December 1999.

- "COTE D'IVOIRE: Former Prime Minister returns home", IRIN, 4 January 2000.

- "Jul 2000 – Referendum on new constitution", Keesing's Record of World Events, Volume 46, July 2000 Cote d'Ivoire, p. 43661.

- Daddieh, Cyril K. (2001). "Elections and Ethnic Violence in Côte d'Ivoire: The Unfinished Business of Succession and Democratic Transition". African Issues. 29 (1–2): 14–19. doi:10.2307/1167104.

- "La présidentielle envisagée par Gbagbo pour fin 2007", L'Humanité, 8 August 2007 (in French).

- "Alassane Ouattara prêt à s'associer aux ex-rebelles", AFP, 3 February 2008.

- ""We Don't Believe Gbagbo Will Organise Transparent Elections" Michael Deibert interviews Alassane Ouattara". Inter Press Service. 23 October 2007. Archived from the original on 26 August 2011.

- "Thousands flee Ivory Coast for Liberia amid poll crisis". BBC News. 26 December 2010. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- "Final Communique on the Extraordinary Session of the Authority of Heads of State and Government on Cote D’Ivoire" Archived 3 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), 7 December 2010.

- "Communique of the 252nd Meeting of the Peace and Security Council" Archived 6 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine, African Union, 9 December 2010.

- "ICE deports Ivory Coast army colonel convicted of arms trafficking". Immigration and Customs Enforcement. 30 November 2012.

- "FBI nabbed colonel on official business", UPI, 21 September 2010.

- United States Court of Appeals Memorandum, 18 December 2015.

- DiCampo, Peter (27 April 2011). "An Uncertain Future". Ivory Coast: Elections Turn to War. Pulitzer Center.

- Lynch, Colum; Branigin, William (11 April 2011). "Ivory Coast strongman arrested after French forces intervene". The Washington Post. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- Griffiths, Thalia (11 April 2011). "The war is over — but Ouattara's struggle has barely begun". The Guardian. London.

- "Obama, Clinton welcome new developments". CNN. 11 April 2011. Archived from the original on 12 April 2011. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- Ouattara dissolves Ivorian government over marriage law, United Kingdom: BBC News, 2012, retrieved 16 November 2012

- Sylvestre-Treiner, Anna, "Côte d’Ivoire : Alassane Ouattara choisit Henriette Dagri Diabaté pour présider son parti", Jeune Afrique, 10 September 2017 (in French).

- Ivorians react to Ouattara’s exit. africanews.com, 6 March 2020

- Ivory Coast court clears President Ouattara's contentious third-term bid. Deutsche Welle (dw.com), 15 September 2020

External links

(in French) Alassane Ouattara.com Political Web site from Ouattara's circle of influence.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Félix Houphouët-Boigny |

Prime Minister of the Ivory Coast 1990–1993 |

Succeeded by Daniel Kablan Duncan |

| Preceded by Laurent Gbagbo |

President of the Ivory Coast 2010–2020 |

Succeeded by Henri Konan Bédié |

| Diplomatic posts | ||

| Preceded by Goodluck Jonathan |

Chairperson of the Economic Community of West African States 2012–2014 |

Succeeded by John Dramani Mahama |