Alcohols (medicine)

Alcohols, in various forms, are used within medicine as an antiseptic, disinfectant, and antidote.[1] Alcohols applied to the skin are used to disinfect skin before a needle stick and before surgery.[2] They may be used both to disinfect the skin of the person and the hands of the healthcare providers.[2] They can also be used to clean other areas[2] and in mouthwashes.[3][4][5] Taken by mouth or injected into a vein, ethanol is used to treat methanol or ethylene glycol toxicity when fomepizole is not available.[1]

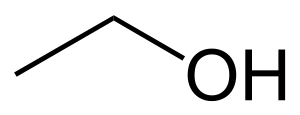

Ethanol is a commonly used medical alcohol. | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Topical, intravenous, by mouth |

| Drug class | Antiseptics, disinfectants, antidotes |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

Side effects of alcohols applied to the skin include skin irritation.[2] Care should be taken with electrocautery, as ethanol is flammable.[1] Types of alcohol used include ethanol, denatured ethanol, 1-propanol, and isopropyl alcohol.[6][7] Alcohols are effective against a range of microorganisms, though they do not inactivate spores.[7] Concentrations of 60 to 90% work best.[7]

Alcohol has been used as an antiseptic as early as 1363, with evidence to support its use becoming available in the late 1800s.[8] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[9] Commercial formulations of alcohol based hand rub or with other agents such as chlorhexidine are available.[7][10]

Medical uses

Applied to the skin, alcohols are used to disinfect skin before a needle stick and before surgery.[2] They may be used both to disinfect the skin of the person and the hands of the healthcare providers.[2] They can also be used to clean other areas,[2] and in mouthwashes.[3] Taken by mouth or injected into a vein ethanol is used to treat methanol or ethylene glycol toxicity when fomepizole is not available.[1]

Aside from these uses, ethanol has no other well-accepted medical uses.[11] This is partly because the therapeutic index of ethanol is 10:1.[12]

Methanol poisoning

Taken by mouth or injected into a vein ethanol is used to treat methanol or ethylene glycol toxicity when fomepizole is not available.[1]

Mechanism

Ethanol, when used for toxicity, competes with other alcohols for the alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme, lessening metabolism into toxic aldehyde and carboxylic acid derivatives, and reducing more serious toxic effect of the glycols to crystallize in the kidneys.[13]

History

Alcohol has been used as an antiseptic as early as 1363 with evidence to support its use becoming available in the late 1800s.[8] Since antiquity, prior to the development of modern agents, alcohol was used as a general anesthetic.[14]

References

- British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. pp. 42, 838. ISBN 9780857111562.

- World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 321. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- Hardy Limeback (11 April 2012). Comprehensive Preventive Dentistry. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-1-118-28020-1. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017.

- Moni Abraham Kuriakose (8 December 2016). Contemporary Oral Oncology: Biology, Epidemiology, Etiology, and Prevention. Springer. pp. 47–54. ISBN 978-3-319-14911-0. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017.

- Jameel RA, Khan SS, Kamaruddin MF, Abd Rahim ZH, Bakri MM, Abdul Razak FB (2014). "Is synthetic mouthwash the final choice to treat oral malodour?". Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan. 24 (10): 757–62. doi:10.2004/JCPSP.757762 (inactive 11 January 2021). PMID 25327922.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- McDonnell G, Russell AD (January 1999). "Antiseptics and disinfectants: activity, action, and resistance". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12 (1): 147–79. doi:10.1128/cmr.12.1.147. PMC 88911. PMID 9880479.

- Block, Seymour Stanton (2001). Disinfection, Sterilization, and Preservation. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 14. ISBN 9780683307405. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Bolon MK (September 2016). "Hand Hygiene: An Update". Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 30 (3): 591–607. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2016.04.007. PMID 27515139.

- Pohorecky LA, Brick J (1988). "Pharmacology of ethanol". Pharmacol. Ther. 36 (2–3): 335–427. doi:10.1016/0163-7258(88)90109-x. PMID 3279433.

- Becker DE (2007). "Drug therapy in dental practice: general principles. Part 2 - pharmacodynamic considerations". Anesth Prog. 54 (1): 19–23, quiz 24–5. doi:10.2344/0003-3006(2007)54[19:DTIDPG]2.0.CO;2. PMC 1821133. PMID 17352523.

- Barceloux DG, Bond GR, Krenzelok EP, Cooper H, Vale JA (2002). "American Academy of Clinical Toxicology practice guidelines on the treatment of methanol poisoning". J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 40 (4): 415–46. doi:10.1081/CLT-120006745. PMID 12216995. S2CID 26495651.

- Edmond I Eger II; Lawrence J. Saidman; Rod N. Westhorpe (14 September 2013). The Wondrous Story of Anesthesia. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-1-4614-8441-7. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017.