Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, commonly known as Interwar Poland, refers to the country of Poland in the period between the two World Wars (1918–1939). Officially known as the Republic of Poland (Polish: Rzeczpospolita Polska), the Polish state was re-established in 1918, in the aftermath of World War I. The Second Republic ceased to exist in 1939, when Poland was invaded by Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union and the Slovak Republic, marking the beginning of the European theatre of World War II.

Republic of Poland | |

|---|---|

| 1918–1939 | |

.svg.png.webp) Flag

(1927–1939) .svg.png.webp) Coat of arms

(1927–1939) | |

The Second Polish Republic in 1930 | |

| Capital and largest city | Warsaw 52°14′N 21°1′E |

| Official languages | Polish |

| Minority languages | |

| Religion (1931) | Majority: 64.8% Roman Catholicism Minorities: |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic (1918–1935) Unitary presidential constitutional republic (1935–1939) |

| President | |

• 1918–1922 | Józef Piłsudskia |

• 1922 | Gabriel Narutowicz |

• 1922–1926 | S. Wojciechowski |

• 1926–1939 | Ignacy Mościcki |

| Prime Minister | |

• 1918–1919 (first) | Jędrzej Moraczewski |

• 1936–1939 (last) | Felicjan S. Składkowski |

| Legislature | Sejm |

• Upper chamber | Senate |

• Lower chamber | Sejm |

| Establishment | |

| Historical era | Interbellum |

• End of World War I | 11 November 1918 |

| 28 June 1919 | |

| 18 March 1921 | |

| 1 September 1939 | |

| 17 September 1939 | |

| 28 September 1939 | |

| 6 October 1939 | |

| Area | |

| 1921 | 387,000 km2 (149,000 sq mi) |

| 1931 | 388,634 km2 (150,052 sq mi) |

| 1938 | 389,720 km2 (150,470 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 1921 | 27,177,000 |

• 1931 | 32,107,000 |

• 1938 | 34,849,000 |

| Currency | Marka (until 1924) Złoty (after 1924) |

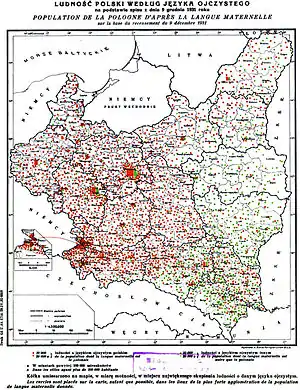

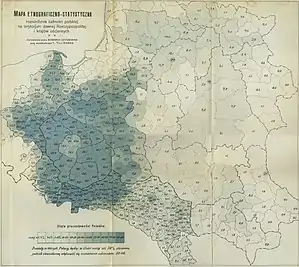

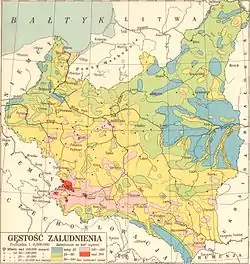

In 1938, the Second Republic was the sixth largest country in Europe. According to the 1921 census, the number of inhabitants was 27.2 million. By 1939, just before the outbreak of World War II, this had grown to an estimated 35.1 million. Almost a third of the population came from minority groups: 13.9% Ruthenians; 10% Ashkenazi Jews; 3.1% Belarusians; 2.3% Germans and 3.4% Czechs and Lithuanians. At the same time, a significant number of ethnic Poles lived outside the country's borders.

When, after several regional conflicts, the borders of the state were finalized in 1922, Poland's neighbors were Czechoslovakia, Germany, the Free City of Danzig, Lithuania, Latvia, Romania and the Soviet Union. It had access to the Baltic Sea via a short strip of coastline either side of the city of Gdynia, known as the Polish Corridor. Between March and August 1939, Poland also shared a border with the then-Hungarian governorate of Subcarpathia. The political conditions of the Second Republic were heavily influenced by the aftermath of World War I and conflicts with neighbouring states as well as the emergence of Nazism in Germany.

The Second Republic maintained moderate economic development. The cultural hubs of interwar Poland – Warsaw, Kraków, Poznań, Wilno and Lwów – became major European cities and the sites of internationally acclaimed universities and other institutions of higher education.

The political borders of interwar Poland were distinctly different from modern Poland, as it contained less territory in the west and more territory in the east.

Background

After more than a century of Partitions between the Austrian, the Prussian, and the Russian imperial powers, Poland re-emerged as a sovereign state at the end of the First World War in Europe in 1917–1918.[1][2][3] The victorious Allies of World War I confirmed the rebirth of Poland in the Treaty of Versailles of June 1919. It was one of the great stories of the 1919 Paris Peace Conference.[4] Poland solidified its independence in a series of border wars fought by the newly formed Polish Army from 1918 to 1921.[5] The extent of the eastern half of the interwar territory of Poland was settled diplomatically in 1922 and internationally recognized by the League of Nations.[6][7]

End of World War I

In the course of World War I (1914-1918), Germany gradually gained overall dominance on the Eastern Front as the Imperial Russian Army fell back. German and Austro-Hungarian armies seized the Russian-ruled part of what became Poland. In a failed attempt to resolve the Polish question as quickly as possible, Berlin set up a German puppet state on 5 November 1916, with a governing Provisional Council of State and (from 15 October 1917) a Regency Council (Rada Regencyjna Królestwa Polskiego). The Council administered the country under German auspices (see also Mitteleuropa), pending the election of a king. A month before Germany surrendered on 11 November 1918 and the war ended, the Regency Council had dissolved the Provisional Council of State and announced its intention to restore Polish independence (7 October 1918). With the notable exception of the Marxist-oriented Social Democratic Party of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL), most Polish political parties supported this move. On 23 October the Regency Council appointed a new government under Józef Świeżyński and began conscription into the Polish Army.[8]

Formation of the Republic

In 1918–1919, over 100 workers' councils sprang up on Polish territories;[9] on 5 November 1918, in Lublin, the first Soviet of Delegates was established. On 6 November socialists proclaimed the Republic of Tarnobrzeg at Tarnobrzeg in Austrian Galicia. The same day the Socialist, Ignacy Daszyński, set up a Provisional People's Government of the Republic of Poland (Tymczasowy Rząd Ludowy Republiki Polskiej) in Lublin. On Sunday, 10 November at 7 a.m., Józef Piłsudski, newly freed from 16 months in a German prison in Magdeburg, returned by train to Warsaw. Piłsudski, together with Colonel Kazimierz Sosnkowski, was greeted at Warsaw's railway station by Regent Zdzisław Lubomirski and by Colonel Adam Koc. Next day, due to his popularity and support from most political parties, the Regency Council appointed Piłsudski as Commander in Chief of the Polish Armed Forces. On 14 November, the Council dissolved itself and transferred all its authority to Piłsudski as Chief of State (Naczelnik Państwa). After consultation with Piłsudski, Daszyński's government dissolved itself and a new government formed under Jędrzej Moraczewski. In 1918 Italy became the first country in Europe to recognize Poland's renewed sovereignty.[10]

Centers of government that formed at that time in Galicia (formerly Austrian-ruled southern Poland) included the National Council of the Principality of Cieszyn (established in November 1918), the Republic of Zakopane and the Polish Liquidation Committee (28 October). Soon afterward, the Polish–Ukrainian War broke out in Lwów (1 November 1918) between forces of the Military Committee of Ukrainians and the Polish irregular units made up of students known as the Lwów Eaglets, who were later supported by the Polish Army (see Battle of Lwów (1918), Battle of Przemyśl (1918)). Meanwhile, in western Poland, another war of national liberation began under the banner of the Greater Poland uprising (1918–19). In January 1919 Czechoslovak forces attacked Polish units in the area of Zaolzie (see Polish–Czechoslovak War). Soon afterwards the Polish–Lithuanian War (ca 1919-1920) began, and in August 1919 Polish-speaking residents of Upper Silesia initiated a series of three Silesian Uprisings. The most critical military conflict of that period, however, the Polish–Soviet War (1919-1921), ended in a decisive Polish victory.[11] In 1919 the Warsaw government suppressed the Republic of Tarnobrzeg and the workers' councils.

Politics and government

.jpg.webp)

The Second Polish Republic was a parliamentary democracy from 1919 (see Small Constitution of 1919) to 1926, with the President having limited powers. The Parliament elected him, and he could appoint the Prime Minister as well as the government with the Sejm's (lower house's) approval, but he could only dissolve the Sejm with the Senate's consent. Moreover, his power to pass decrees was limited by the requirement that the Prime Minister and the appropriate other Minister had to verify his decrees with their signatures. Poland was one of the first countries in the world to recognize women's suffrage. Women in Poland were granted the right to vote on 28 November 1918 by a decree of Józef Piłsudski.[12]

The major political parties at this time were the Polish Socialist Party, National Democrats, various Peasant Parties, Christian Democrats, and political groups of ethnic minorities (German: German Social Democratic Party of Poland, Jewish: General Jewish Labour Bund in Poland, United Jewish Socialist Workers Party, and Ukrainian: Ukrainian National Democratic Alliance). Frequently changing governments (see 1919 Polish legislative election, 1922 Polish legislative election) and other negative publicity the politicians received (such as accusations of corruption or 1919 Polish coup attempt), made them increasingly unpopular. Major politicians at this time, in addition to Piłsudski, included peasant activist Wincenty Witos (Prime Minister three times) and right-wing leader Roman Dmowski. Ethnic minorities were represented in the Sejm; e.g. in 1928 – 1930 there was the Ukrainian-Belarusian Club, with 26 Ukrainian and 4 Belarusian members.

After the Polish – Soviet war, Marshal Piłsudski led an intentionally modest life, writing historical books for a living. After he took power by a military coup in May 1926, he emphasized that he wanted to heal the Polish society and politics of excessive partisan politics. His regime, accordingly, was called Sanacja in Polish. The 1928 parliamentary elections were still considered free and fair, although the pro-Piłsudski Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government won them. The following three parliamentary elections (in 1930, 1935 and 1938) were manipulated, with opposition activists sent to Bereza Kartuska prison (see also Brest trials). As a result, pro-government party Camp of National Unity won huge majorities in them. Piłsudski died just after an authoritarian constitution was approved in the spring of 1935. During the last four years of the Second Polish Republic, the major politicians included President Ignacy Mościcki, Foreign Minister Józef Beck and the Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Army, Edward Rydz-Śmigły. The country was divided into 104 electoral districts, and those politicians who were forced to leave Poland, founded Front Morges in 1936. The government that ruled Second Polish Republic in its final years is frequently referred to as Piłsudski's colonels.[13]

|

Presidents and Prime ministers (November 1918 – September 1939)  President of Poland Ignacy Mościcki (left), Warsaw, 10 November 1936, awarding the Marshal's buława to Edward Rydz-Śmigły

Chief of State

Presidents

Prime ministers

|

Military

Interwar Poland had a considerably large army of 950,000 soldiers on active duty: in 37 infantry divisions, 11 cavalry brigades, and two armored brigades, plus artillery units. Another 700,000 men served in the reserves. At the outbreak of the war, the Polish army was able to put in the field almost one million soldiers, 4,300 guns, 1,280 tanks and 745 aircraft.[14]

The training of the Polish Army was thorough. The non-commissioned officers were a competent body of men with expert knowledge and high ideals. The officers, both senior and junior, constantly refreshed their training in the field and in the lecture-hall, where modern technical achievement and the lessons of contemporary wars were demonstrated and discussed. The equipment of the Polish army was less developed technically than that of Nazi Germany and its rearmament was slowed down by confidence in Western European military support and by budget difficulties.[15]

Economy

After regaining its independence, Poland was faced with major economic difficulties. In addition to the devastation brought by World War I, the exploitation of the Polish economy by the German and Russian occupying powers, and the sabotage performed by retreating armies, the new republic was faced with the task of economically unifying disparate economic regions, which had previously been part of different countries.[16] Within the borders of the Republic were the remnants of three different economic systems, with five different currencies (the German mark, the Russian ruble, the Austrian crown, the Polish marka and the Ostrubel)[16] and with little or no direct infrastructural links. The situation was so bad that neighboring industrial centers as well as major cities lacked direct railroad links, because they had been parts of different nations. For example, there was no direct railroad connection between Warsaw and Kraków until 1934. This situation was described by Melchior Wańkowicz in his book Sztafeta.

On top of this was the massive destruction left after both World War I and the Polish–Soviet War. There was also a great economic disparity between the eastern (commonly called Poland B) and western (called Poland A) parts of the country, with the western half, especially areas that had belonged to the German Empire being much more developed and prosperous. Frequent border closures and a customs war with Germany also had negative economic impacts on Poland. In 1924 Prime Minister and Economic Minister Władysław Grabski introduced the złoty as a single common currency for Poland (it replaced the Polish marka), which remained a stable currency. The currency helped Poland to control the massive hyperinflation. It was the only country in Europe able to do this without foreign loans or aid.[17] The average annual growth rate (GDP per capita) was 5.24% in 1920–29 and 0.34% in 1929–38.[18]

| Year | Int$. |

|---|---|

| 1922 | 1,382 |

| 1929 | 2,117 |

| 1930 | 1,994 |

| 1931 | 1,823 |

| 1932 | 1,658 |

| 1933 | 1,590 |

| 1934 | 1,593 |

| 1935 | 1,597 |

| 1936 | 1,626 |

| 1937 | 1,915 |

| 1938 | 2,182 |

Hostile relations with neighbors were a major problem for the economy of interbellum Poland. In the year 1937, foreign trade with all neighbors amounted to only 21% of Poland's total. Trade with Germany, Poland's most important neighbour, accounted for 14.3% of Polish exchange. Foreign trade with the Soviet Union (0.8%) was virtually nonexistent. Czechoslovakia accounted for 3.9%, Latvia for 0.3%, and Romania for 0.8%. By mid-1938, after the Anschluss of Austria, Greater Germany was responsible for as much as 23% of Polish foreign trade.

The basis of Poland's gradual recovery after the Great Depression was its mass economic development plans (see Four Year Plan), which oversaw the building of three key infrastructural elements. The first was the establishment of the Gdynia seaport, which allowed Poland to completely bypass Gdańsk (which was under heavy German pressure to boycott Polish coal exports). The second was construction of the 500-kilometer rail connection between Upper Silesia and Gdynia, called Polish Coal Trunk-Line, which served freight trains with coal. The third was the creation of a central industrial district, named COP – Central Industrial Region (Centralny Okręg Przemysłowy). Unfortunately, these developments were interrupted and largely destroyed by the German and Soviet invasion and the start of World War II.[20] Other achievements of interbellum Poland included Stalowa Wola (a brand new city, built in a forest around a steel mill), Mościce (now a district of Tarnów, with a large nitrate factory), and the creation of a central bank. There were several trade fairs, with the most popular being Poznań International Fair, Lwów's Targi Wschodnie, and Wilno's Targi Północne. Polish Radio had ten stations (see Radio stations in interwar Poland), with the eleventh one planned to be opened in the autumn of 1939. Furthermore, in 1935 Polish engineers began working on the TV services. By early 1939, experts of the Polish Radio built four TV sets. The first movie broadcast by experimental Polish TV was Barbara Radziwiłłówna, and by 1940, regular TV service was scheduled to begin operation.[21]

Interbellum Poland was also a country with numerous social problems. Unemployment was high, and poverty in the countryside was widespread, which resulted in several cases of social unrest, such as the 1923 Kraków riot, and 1937 peasant strike in Poland. There were conflicts with national minorities, such as Pacification of Ukrainians in Eastern Galicia (1930), relations with Polish neighbors were sometimes complicated (see Soviet raid on Stołpce, Polish–Czechoslovak border conflicts, 1938 Polish ultimatum to Lithuania). On top of this, there were natural disasters, such as the 1934 flood in Poland.

Major industrial centers

.JPG.webp)

Interbellum Poland was unofficially divided into two parts – better developed "Poland A" in the west, and underdeveloped "Poland B" in the east. Polish industry was concentrated in the west, mostly in Polish Upper Silesia, and the adjacent Lesser Poland's province of Zagłębie Dąbrowskie, where the bulk of coal mines and steel plants was located. Furthermore, heavy industry plants were located in Częstochowa (Huta Częstochowa, founded in 1896), Ostrowiec Świętokrzyski (Huta Ostrowiec, founded in 1837–1839), Stalowa Wola (brand new industrial city, which was built from scratch in 1937 – 1938), Chrzanów (Fablok, founded in 1919), Jaworzno, Trzebinia (oil refinery, opened in 1895), Łódź (the seat of Polish textile industry), Poznań (H. Cegielski – Poznań), Kraków and Warsaw (Ursus Factory). Further east, in Kresy, industrial centers included two major cities of the region – Lwów and Wilno (Elektrit).[22]

Besides coal mining, Poland also had deposits of oil in Borysław, Drohobycz, Jasło and Gorlice (see Polmin), potassium salt (TESP), and basalt (Janowa Dolina). Apart from already-existing industrial areas, in the mid-1930s, an ambitious, state-sponsored project of Central Industrial Region was started under Minister Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski. One of characteristic features of Polish economy in the interbellum was gradual nationalization of major plants. This was the case of Ursus Factory (see Państwowe Zakłady Inżynieryjne), and several steelworks, such as Huta Pokój in Ruda Śląska – Nowy Bytom, Huta Królewska in Chorzów – Królewska Huta, Huta Laura in Siemianowice Śląskie, as well as Scheibler and Grohman Works in Łódź.[22]

Transport

According to the 1939 Statistical Yearbook of Poland, the total length of railways of Poland (as of 31 December 1937) was 20,118 kilometres (12,501 miles). Rail density was 5.2 kilometres (3.2 miles) per 100 square kilometres (39 square miles). Railways were very dense in the western part of the country, while in the east, especially Polesie, rail was non-existent in some counties. During the interbellum period, the Polish government constructed several new lines, mainly in the central part of the country (see also Polish State Railroads Summer 1939). Construction of extensive Warszawa Główna railway station was never finished due to the war, and Polish railroads were famous for their punctuality (see Luxtorpeda, Strzała Bałtyku, Latający Wilnianin).

In the interbellum, the road network of Poland was dense, but the quality of the roads was very poor – only 7% of all roads was paved and ready for automobile use, and none of the major cities were connected with each other by a good-quality highway. In 1939 the Poles built only one highway: 28 km of straight concrete road connecting the villages of Warlubie and Osiek (mid-northern Poland). It was designed by Italian engineer Piero Puricelli.

_w_Gda%C5%84sku.JPG.webp)

In the mid-1930s, Poland had 340,000 kilometres (211,266 miles) of roads, but only 58,000 had a hard surface (gravel, cobblestone or sett), and 2,500 were modern, with an asphalt or concrete surface. In different parts of the country, there were sections of paved roads, which suddenly ended, and were followed by dirt roads.[23] The poor condition of the roads was the result of both long-lasting foreign dominance and inadequate funding. On 29 January 1931, the Polish Parliament created the State Road Fund, the purpose of which was to collect money for the construction and conservation of roads. The government drafted a 10-year plan, with road priorities: a highway from Wilno, through Warsaw and Kraków, to Zakopane (called Marshal Piłsudski Highway), asphalt highways from Warsaw to Poznań and Łódź, as well as a Warsaw ring road. However, the plan turned out to be too ambitious, with insufficient money in the national budget to pay for it. In January 1938, the Polish Road Congress estimated that Poland would need to spend three times as much money on roads to keep up with Western Europe.

In 1939, before the outbreak of the war, LOT Polish Airlines, which was established in 1929, had its hub at Warsaw Okęcie Airport. At that time, LOT maintained several services, both domestic and international. Warsaw had regular domestic connections with Gdynia-Rumia, Danzig-Langfuhr, Katowice-Muchowiec, Kraków-Rakowice-Czyżyny, Lwów-Skniłów, Poznań-Ławica, and Wilno-Porubanek. Furthermore, in cooperation with Air France, LARES, Lufthansa, and Malert, international connections were maintained with Athens, Beirut, Berlin, Bucharest, Budapest, Helsinki, Kaunas, London, Paris, Prague, Riga, Rome, Tallinn, and Zagreb.[24]

Agriculture

Statistically, the majority of citizens lived in the countryside (75% in 1921). Farmers made up 65% of the population. In 1929, agricultural production made up 65% of Poland's GNP.[25] After 123 years of partitions, regions of the country were very unevenly developed. Lands of former German Empire were most advanced; in Greater Poland and Pomerelia, crops were on Western European level.[26] The situation was much worse in parts of Congress Poland, Eastern Borderlands, and former Galicia, where agriculture was most backward and primitive, with a large number of small farms, unable to succeed in either the domestic and international market. Another problem was the overpopulation of the countryside, which resulted in chronic unemployment. Living conditions were so bad in several eastern regions, such as counties inhabited by the Hutsul minority, that there was permanent starvation.[27] Farmers rebelled against the government (see: 1937 peasant strike in Poland), and the situation began to change in the late 1930s, due to construction of several factories for the Central Industrial Region, which gave employment to thousands of countryside residents.

German trade

Beginning in June 1925 there was a customs' war with the revanchist Weimar Republic imposing trade embargo against Poland for nearly a decade; involving tariffs, and broad economic restrictions. After 1933 the trade war ended. The new agreements regulated and promoted trade. Germany became Poland's largest trading partner, followed by Britain. In October 1938 Germany granted a credit of Rm 60,000,000 to Poland (120,000,000 zloty, or £4,800,000) which was never realized, due to the outbreak of war. Germany would deliver factory equipment and machinery in return for Polish timber and agricultural produce. This new trade was to be in addition to the existing German-Polish trade agreements.[28][29]

Education and culture

In 1919, the Polish government introduced compulsory education for all children aged 7 to 14, in an effort to limit illiteracy, which was widespread especially in the former Russian Partition and the Austrian Partition of eastern Poland. In 1921, one-third of citizens of Poland remained illiterate (38% in the countryside). The process was slow, but by 1931, the illiteracy level had dropped to 23% overall (27% in the countryside) and further down to 18% in 1937. By 1939, over 90% of children attended school.[22][30] In 1932, Minister of Religion and Education Janusz Jędrzejewicz carried out a major reform which introduced two main levels of education: common school (szkoła powszechna), with three levels – 4 grades + 2 grades + 1 grade; and middle school (szkoła średnia), with two levels – 4 grades of comprehensive middle school and 2 grades of specified high school (classical, humanistic, natural and mathematical). A graduate of middle school received a small matura, while a graduate of high school received a big matura, which enabled them to seek university-level education.

Before 1918, Poland had three universities: Jagiellonian University, University of Warsaw and Lwów University. Catholic University of Lublin was established in 1918; Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, in 1919; and finally, in 1922, after the annexation of Republic of Central Lithuania, Wilno University became the Republic's sixth university. There were also three technical colleges: the Warsaw University of Technology, Lwów Polytechnic and the AGH University of Science and Technology in Kraków, established in 1919. Warsaw University of Life Sciences was an agricultural institute. By 1939, there were around 50,000 students enrolled in further education. Women made up 28% of university students, the second highest proportion in Europe.[31]

Polish science in the interbellum was renowned for its mathematicians gathered around the Lwów School of Mathematics, the Kraków School of Mathematics, as well as Warsaw School of Mathematics. There were world-class philosophers in the Lwów–Warsaw school of logic and philosophy.[32] Florian Znaniecki founded Polish sociological studies. Rudolf Weigl invented a vaccine against typhus. Bronisław Malinowski counted among the most important anthropologists of the 20th century.

In Polish literature, the 1920s were marked by the domination of poetry. Polish poets were divided into two groups – the Skamanderites (Jan Lechoń, Julian Tuwim, Antoni Słonimski and Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz) and the Futurists (Anatol Stern, Bruno Jasieński, Aleksander Wat, Julian Przyboś). Apart from well-established novelists (Stefan Żeromski, Władysław Reymont), new names appeared in the interbellum – Zofia Nałkowska, Maria Dąbrowska, Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, Jan Parandowski, Bruno Schultz, Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Witold Gombrowicz. Among other notable artists there were sculptor Xawery Dunikowski, painters Julian Fałat, Wojciech Kossak and Jacek Malczewski, composers Karol Szymanowski, Feliks Nowowiejski, and Artur Rubinstein, singer Jan Kiepura.

Theatre was immensely popular in the interbellum, with three main centers in the cities of Warsaw, Wilno and Lwów. Altogether, there were 103 theaters in Poland and a number of other theatrical institutions (including 100 folk theaters). In 1936, different shows were seen by 5 million people, and main figures of Polish theatre of the time were Juliusz Osterwa, Stefan Jaracz, and Leon Schiller. Also, before the outbreak of the war, there were approximately one million radios (see Radio stations in interwar Poland).

Administrative division

The administrative division of the Republic was based on a three-tier system. On the lowest rung were the gminy, local town and village governments akin to districts or parishes. These were then grouped together into powiaty (akin to counties), which, in turn, were grouped as województwa (voivodeships, akin to provinces).

| Polish voivodeships (1 April 1937) | |||||

| Car plates (starting 1937) |

Voivodeship or city |

Capital | Area (1930) in 1,000s km2 |

Population (1931) in 1,000s | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 00–19 | City of Warsaw | Warsaw | 0.14 | 1,179.5 | |

| 85–89 | warszawskie | Warsaw | 31.7 | 2,460.9 | |

| 20–24 | białostockie | Białystok | 26.0 | 1,263.3 | |

| 25–29 | kieleckie | Kielce | 22.2 | 2,671.0 | |

| 30–34 | krakowskie | Kraków | 17.6 | 2,300.1 | |

| 35–39 | lubelskie | Lublin | 26.6 | 2,116.2 | |

| 40–44 | lwowskie | Lwów | 28.4 | 3,126.3 | |

| 45–49 | łódzkie | Łódź | 20.4 | 2,650.1 | |

| 50–54 | nowogródzkie | Nowogródek | 23.0 | 1,057.2 | |

| 55–59 | poleskie (Polesia) | Brześć nad Bugiem | 36.7 | 1,132.2 | |

| 60–64 | pomorskie (Pomeranian) | Toruń | 25.7 | 1,884.4 | |

| 65–69 | poznańskie | Poznań | 28.1 | 2,339.6 | |

| 70–74 | stanisławowskie | Stanisławów | 16.9 | 1,480.3 | |

| 75–79 | śląskie (Silesian) | Katowice | 5.1 | 1,533.5 | |

| 80–84 | tarnopolskie | Tarnopol | 16.5 | 1,600.4 | |

| 90–94 | wileńskie | Wilno | 29.0 | 1,276.0 | |

| 95–99 | wołyńskie (Volhynian) | Łuck | 35.7 | 2,085.6 | |

| The borders of several western and central voivodeships were revised on 1 April 1938 | |||||

Demographics

Historically, Poland was a nation of many nationalities. This was especially true after independence was regained in the wake of World War I and the subsequent Polish–Soviet War ending at Peace of Riga. The census of 1921 shows 30.8% of the population consisted of ethnic minorities,[35] compared with a share of 1.6% (solely identifying with a non-Polish ethnic group) or 3.8% (including those identifying with both the Polish ethnicity and with another ethnic group) in 2011.[36] The first spontaneous flight of about 500,000 Poles from the Soviet Union occurred during the reconstitution of sovereign Poland. In the second wave, between November 1919 and June 1924 some 1,200,000 people left the territory of the USSR for Poland. It is estimated that some 460,000 of them spoke Polish as the first language.[37] According to the 1931 Polish Census: 68.9% of the population was Polish, 13.9% were Ukrainian, around 10% Jewish, 3.1% Belarusian, 2.3% German and 2.8% other, including Lithuanian, Czech, Armenian, Russian, and Romani. The situation of minorities was a complex subject and changed during the period.[5]

Poland was also a nation of many religions. In 1921, 16,057,229 Poles (approx. 62.5%) were Roman (Latin) Catholics, 3,031,057 citizens of Poland (approx. 11.8%) were Eastern Rite Catholics (mostly Ukrainian Greek Catholics and Armenian Rite Catholics), 2,815,817 (approx. 10.95%) were Greek Orthodox, 2,771,949 (approx. 10.8%) were Jewish, and 940,232 (approx. 3.7%) were Protestants (mostly Lutheran).[38]

By 1931, Poland had the second largest Jewish population in the world, with one-fifth of all the world's Jews residing within its borders (approx. 3,136,000).[35] The urban population of interbellum Poland was rising steadily; in 1921, only 24% of Poles lived in the cities, in the late 1930s, that proportion grew to 30%. In more than a decade, the population of Warsaw grew by 200,000, Łódź by 150,000, and Poznań – by 100,000. This was due not only to internal migration, but also to an extremely high birth rate.[22]

Largest cities in the Second Polish Republic

| City | Population | Voivodeship | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,289,000 | Warsaw Voivodeship | |

| 2 | 672,000 | Łódź Voivodeship | |

| 3 | 318,000 | Lwów Voivodeship | |

| 4 | 272,000 | Poznań Voivodeship | |

| 5 | 259,000 | Kraków Voivodeship | |

| 6 | 209,000 | Wilno Voivodeship | |

| 7 | 141,000 | Poznań Voivodeship later Pomeranian Voivodeship | |

| 8 | 138,000 | Kielce Voivodeship | |

| 9 | 134,000 | Silesian Voivodeship | |

| 10 | 130,000 | Kielce Voivodeship | |

| 11 | 128,000 | Silesian Voivodeship | |

| 12 | 122,000 | Lublin Voivodeship | |

| 13 | 120,000 | Pomeranian Voivodeship | |

| 14 | 107,000 | Białystok Voivodeship | |

| 15 | 81,000 | Poznań Voivodeship | |

| 16 | 78,000 | Kielce Voivodeship | |

| 17 | 62,000 | Pomeranian Voivodeship | |

| 18 | 60,000 | Stanisławów Voivodeship | |

| 19 | 58,000 | Kielce Voivodeship | |

| 20 | 56,000 | Pomeranian Voivodeship | |

| 21 | 54,000 | Pomeranian Voivodeship | |

| 22 | 51,000 | Polesie Voivodeship | |

| 23 | 51,000 | Łódź Voivodeship | |

| 24 | 51,000 | Lwów Voivodeship |

Prewar population density

| Date | Population | Percentage of rural population | Population density (per km2) | Ethnic minorities (total) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 September 1921 (census) | 27,177,000 | 75.4% | 69.9 | 30,77%[35] |

| 9 December 1931 (census) | 32,348,000 | 72.6% | 82.6 | 31.09% |

| 31 December 1938 (estimate) | 34,849,000 | 70.0% | 89.7 | Upward trend in immigration |

Status of ethnic minorities

Jews

From the 1920s the Polish government excluded Jews from receiving government bank loans, public sector employment, and obtaining business licenses. From the 1930s measures were taken against Jewish shops, Jewish export firms, Shechita as well as limitations were placed on Jewish admission to the medical and legal professions, Jews in business associations and the enrollment of Jews into universities. The far-right National Democracy (Endecja from the abbreviation "ND") often organized anti-Jewish boycotts.[39] Following the death of Józef Piłsudski in 1935, the Endecja intensified their efforts which triggered violence in extreme cases in smaller towns across the country.[39] In 1937, the National Democracy movement passed resolutions that "its main aim and duty must be to remove the Jews from all spheres of social, economic, and cultural life in Poland".[39] The government in response organized the Camp of National Unity (OZON), which in 1938 took control of the Polish Sejm and subsequently drafted anti-Semitic legislation similar to the Anti-Jewish laws in Germany, Hungary, and Romania. OZON advocated mass emigration of Jews from Poland, numerus clausus (see also Ghetto benches), and other limitation on Jewish rights. According to William W. Hagen by 1939, prior to the war, Polish Jews were threatened with conditions similar to those in Nazi Germany.[40]

Ukrainians

The pre-war government also restricted rights of people who declared Ukrainian nationality, belonged to the Eastern Orthodox Church and inhabited the Eastern Borderlands of the Second Polish Republic.[41][42][43] The Ukrainian language was restricted in every field possible, especially in governmental institutions, and the term "Ruthenian" was enforced in an attempt to ban the use of the term "Ukrainian".[44] Ukrainians were categorized as uneducated second-class peasants or third world people and rarely settled outside the Eastern Borderland region due to the prevailing Ukrainophobia and restrictions imposed. Numerous attempts at restoring the Ukrainian state were suppressed and any existent violence or terrorism initiated by the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists was emphasized to create an image of a "brutal Eastern savage".[45]

Geography

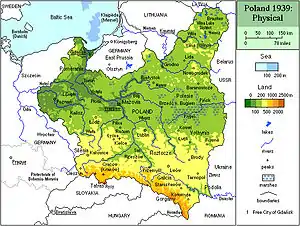

The Second Polish Republic was mainly flat with average elevation of 233 metres (764 ft) above sea level, except for the southernmost Carpathian Mountains (after World War II and its border changes, the average elevation of Poland decreased to 173 metres (568 ft)). Only 13% of territory, along the southern border, was higher than 300 metres (980 ft). The highest elevation in the country was Mount Rysy, which rises 2,499 metres (8,199 ft) in the Tatra Range of the Carpathians, approximately 95 kilometres (59 miles) south of Kraków. Between October 1938 and September 1939, the highest elevation was Lodowy Szczyt (known in the Slovak language as Ľadový štít), which rises 2,627 metres (8,619 ft) above sea level. The largest lake was Lake Narach.

The country's total area, after the annexation of Zaolzie, was 389,720 square kilometres (150,470 sq mi). It extended 903 kilometres (561 miles) from north to south and 894 kilometres (556 miles) from east to west. On 1 January 1938, total length of boundaries was 5,529 kilometres (3,436 miles), including: 140 kilometres (87 miles) of coastline (out of which 71 kilometres (44 miles) were made by the Hel Peninsula), the 1,412 kilometres (877 miles) with Soviet Union, 948 kilometers with Czechoslovakia (until 1938), 1,912 kilometres (1,188 miles) with Germany (together with East Prussia), and 1,081 kilometres (672 miles) with other countries (Lithuania, Romania, Latvia, Danzig). The warmest yearly average temperature was in Kraków among major cities of the Second Polish Republic, at 9.1 °C (48.4 °F) in 1938; and the coldest in Wilno (7.6 °C or 45.7 °F in 1938). Extreme geographical points of Poland included Przeświata River in Somino to the north (located in the Braslaw county of the Wilno Voivodeship); Manczin River to the south (located in the Kosów county of the Stanisławów Voivodeship); Spasibiorki near railway to Połock to the east (located in the Dzisna county of the Wilno Voivodeship); and Mukocinek near Warta River and Meszyn Lake to the west (located in the Międzychód county of the Poznań Voivodeship).

Waters

Almost 75% of the territory of interbellum Poland was drained northward into the Baltic Sea by the Vistula (total area of drainage basin of the Vistula within boundaries of the Second Polish Republic was 180,300 square kilometres (69,600 square miles), the Niemen (51,600 square kilometres or 19,900 square miles), the Odra (46,700 square kilometres or 18,000 square miles) and the Daugava (10,400 square kilometres or 4,000 square miles). The remaining part of the country was drained southward, into the Black Sea, by the rivers that drain into the Dnieper (Pripyat, Horyn and Styr, all together 61,500 square kilometres or 23,700 square miles) as well as Dniester (41,400 square kilometres or 16,000 square miles)

German–Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939

.jpg.webp)

The Second World War in 1939 ended the sovereign Second Polish Republic. The German invasion of Poland began on 1 September 1939, one week after Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed the secret Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. On that day, Germany and Slovakia attacked Poland, and on 17 September the Soviets attacked eastern Poland. Warsaw fell to the Nazis on 28 September after a twenty-day siege. Open organized Polish resistance ended on 6 October 1939 after the Battle of Kock, with Germany and the Soviet Union occupying most of the country. Lithuania annexed the area of Wilno, and Slovakia seized areas along Poland's southern border - including Górna Orawa and Tatranská Javorina - which Poland had annexed from Czechoslovakia in October 1938. Poland did not surrender to the invaders, but continued fighting under the auspices of the Polish government-in-exile and of the Polish Underground State. After the signing of the German–Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Demarcation on 28 September 1939, Polish areas occupied by Nazi Germany either became directly annexed to the Third Reich, or became part of the General Government. The Soviet Union, following Elections to the People's Assemblies of Western Ukraine and Western Belarus (22 October 1939), annexed eastern Poland partly to the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, and partly to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (November 1939).

Polish war plans (Plan West and Plan East) failed as soon as Germany invaded in 1939. The Polish losses in combat against Germans (killed and missing in action) amounted to ca. 70,000 men. Some 420,000 of them were taken prisoners. Losses against the Red Army (which invaded Poland on 17 September) added up to 6,000 to 7,000 of casualties and MIA, 250,000 were taken prisoners. Although the Polish army – considering the inactivity of the Allies – was in an unfavorable position – it managed to inflict serious losses to the enemies: 20,000 German soldiers were killed or MIA, 674 tanks and 319 armored vehicles destroyed or badly damaged, 230 aircraft shot down; the Red Army lost (killed and MIA) about 2,500 soldiers, 150 combat vehicles and 20 aircraft. The Soviet invasion of Poland, and lack of promised aid from the Western Allies, contributed to the Polish forces defeat by 6 October 1939.

A popular myth is that Polish cavalry armed with lances charged German tanks during the September 1939 campaign. This often repeated account, first reported by Italian journalists as German propaganda, concerned an action by the Polish 18th Lancer Regiment near Chojnice. This arose from misreporting of a single clash on 1 September 1939 near Krojanty, when two squadrons of the Polish 18th Lancers armed with sabers surprised and wiped out a German infantry formation with a mounted saber charge. Shortly after midnight the 2nd (Motorized) Division was compelled to withdraw by Polish cavalry, before the Poles were caught in the open by German armored cars. The story arose because some German armored cars appeared and gunned down 20 troopers as the cavalry escaped. Even this failed to persuade everyone to reexamine their beliefs—there were some who thought Polish cavalry had been improperly employed in 1939.

Between 1939 and 1990, the Polish government-in-exile operated in Paris and later in London, presenting itself as the only legal and legitimate representative of the Polish nation. In 1990 the last president in exile, Ryszard Kaczorowski handed the presidential insignia to the newly elected President, Lech Wałęsa, signifying continuity between the Second and Third republics.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Second Polish Republic. |

- History of Poland (1918–39)

- 1938 in Poland

- 1939 in Poland

- Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also known as the "First Polish Republic" and described as a "republic under the presidency of the King"

References

- Mieczysław Biskupski. The history of Poland. Greenwood Publishing Group. 2000. p. 51. ISBN 0313305714

- Norman Davies. Heart of Europe: The Past in Poland's Present. Oxford University Press. 2001. pp. 100-101. ISBN 0192801260

- Piotr S. Wandycz. The Lands of Partitioned Poland 1795-1918. University of Washington Press. 1974. p. 368. ISBN 0295953586

- MacMillan, Margaret (2007). "17: Poland Reborn". Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World. New York: Random House. p. 207. ISBN 9780307432964.

The rebirth of Poland was one of the great stories of the Paris Peace Conference.

- Norman Davies, God's Playground, Columbia University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-231-12819-3, Google Print, p.299

- Mieczysław B. Biskupski. The origins of modern Polish democracy. Ohio University Press. 2010. p. 130.

- Richard J. Crampton. Atlas of Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century. Routledge. 1997. p. 101. ISBN 1317799518.

- Richard M. Watt, Bitter Glory: Poland and Its Fate, 1918–1939 (1998)

- "Rady Delegatów Robotniczych w Polsce". Internetowa encyklopedia PWN. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- Andrzej Garlicki (1995), Józef Piłsudski, 1867–1935.

- Norman Richard Davies, White Eagle, Red Star: the Polish-Soviet War, 1919–20 (2nd ed. 2003)

- A. Polonsky, Politics in Independent Poland, 1921–1939: The Crisis of Constitutional Government (1972)

- Peter Hetherington, Unvanquished: Joseph Piłsudski, Resurrected Poland, and the Struggle for Eastern Europe (2012); W. Jędrzejewicz, Piłsudski. A Life for Poland (1982)

- David G. Williamson (2011). Poland Betrayed: The Nazi-Soviet Invasions of 1939. Stackpole Books. p. 21. ISBN 9780811708289.

- Walter M. Drzewieniecki,"The Polish Army on the Eve of World War II," Polish Review (1981) 26#3 pp 54–64 in JSTOR

- Nikolaus Wolf, "Path dependent border effects: the case of Poland's reunification (1918–1939)", Explorations in Economic History, 42, 2005, pgs. 414–438

- Godzina zero. Interview with professor Wojciech Roszkowski, Tygodnik Powszechny, 04.11.2008"Także reformę Grabskiego przeprowadziliśmy sami, kosztem społeczeństwa, choć tym razem zapłacili obywatele z wyższych sfer, głównie posiadacze ziemscy."

- Stephen Broadberry, Kevin H. O'Rourke. The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Europe: Volume 2, 1870 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. 2010. pp. 188, 190.

- (1929-1930) Angus Maddison. The World Economy Volume 1: A Millennial Perspective Volume 2: Historical Statistics. Academic Foundation. 2007. p. 478.

- Atlas Historii Polski, Demart Sp, 2004, ISBN 83-89239-89-2

- 70 years of television in Poland, TVP INFO, 26.08.2009

- Witold Gadomski, Spłata długu po II RP. Liberte.pl (in Polish).

- Piotr Osęka, Znoje na wybojach. Polityka weekly, July 21, 2011

- Urzędowy Rozkład Jazy i Lotów, Lato 1939. Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Komunikacji, Warszawa 1939

- Sprawa reformy rolnej w I Sejmie Âlàskim (1922–1929) by Andrzej Drogon

- Godzina zero, interview with Wojciech Roszkowski. 04.11.2008

- Białe plamy II RP, interview with professor Andrzej Garlicki, December 5, 2011

- Wojna celna (German–Polish customs' war) (Internet Archive), Encyklopedia PWN, Biznes.

- Keesing's Contemporary Archives Volume 3, (October 1938) p. 3283.

- Norman Davies (2005), God's Playground A History of Poland: Volume II: 1795 to the Present. Oxford University Press, p. 175. ISBN 0199253390.

- B. G. Smith. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History: 4 Volume Set. Oxford University Press. 2008 p. 470.

- Maria Carla Galavotti, Elisabeth Nemeth, Friedrich Stadler (2013). European Philosophy of Science - Philosophy of Science in Europe and the Viennese Heritage. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 408, 175–176, 180–183. ISBN 978-3319018997.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) Also in: Sandra Lapointe, Jan Wolenski, Mathieu Marion, Wioletta Miskiewicz (2009). The Golden Age of Polish Philosophy: Kazimierz Twardowski's Philosophical Legacy. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 127, 56. ISBN 978-9048124015.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Maliszewski, Edward (1916). Polskość i Polacy na Litwie i Rusi (in Polish) (2nd ed.). PTKraj. pp. 13–14.

- Michael Ellman (2005), Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932-33 Revisited. Europe-Asia Studies. PDF file.

- Joseph Marcus, Social and Political History of the Jews in Poland, 1919–1939, Mouton Publishing, 1983, ISBN 90-279-3239-5, Google Books, p. 17

- "Przynależność narodowo-etniczna ludności – wyniki spisu ludności i mieszkań 2011" [Ethnic makeup of Polish citizenry according to census of 2011] (PDF). Materiał Na Konferencję Prasową W Dniu 2013-01-29: 3, 4 – via PDF file, direct download 192 KB.

- PWN (2016). "Rosja. Polonia i Polacy". Encyklopedia PWN. Stanisław Gregorowicz. Polish Scientific Publishers PWN.

- Powszechny Spis Ludnosci r. 1921

- Timothy Snyder, The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-10586-X p.144

- Hagen, William W. "Before the" final solution": Toward a comparative analysis of political anti-Semitism in interwar Germany and Poland." The Journal of Modern History 68.2 (1996): 351-381.

- Revyuk, Emil (8 July 1931). "Polish Atrocities in Ukraine". Svoboda Press – via Google Books.

- Skalmowski, Wojciech (8 July 2003). For East is East: Liber Amicorum Wojciech Skalmowski. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9789042912984 – via Google Books.

- "The Polish Review". Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences in America. 8 July 2001 – via Google Books.

- Radziejowski, Janusz; Studies, University of Alberta Canadian Institute of Ukrainian (8 July 1983). The Communist Party of Western Ukraine, 1919-1929. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, University of Alberta. ISBN 9780920862254 – via Internet Archive.

ukrainophobia poland rights.

- "II RP nie lubiła Ukraińców?". klubjagiellonski.pl.

Further reading

- Davies, Norman. God's Playground. A History of Poland. Vol. 2: 1795 to the Present. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981. pp 393–434

- Latawaski, Paul. Reconstruction of Poland 1914–23 (1992)

- Leslie, R. F. et al. The History of Poland since 1863. Cambridge U. Press, 1980. 494 pp.

- Lukowski, Jerzy and Zawadzki, Hubert. A Concise History of Poland. Cambridge U. Press, 2nd ed 2006. 408pp. excerpts and search

- Pogonowski, Iwo Cyprian. Poland: A Historical Atlas. Hippocrene, 1987. 321 pp. new designed maps

- Stachura, Peter D. Poland, 1918–1945: An Interpretive and Documentary History of the Second Republic (2004) online

- Stachura, Peter D. ed. Poland Between the Wars, 1918–1939 (1998) essays by scholars

- Watt, Richard M. Bitter Glory: Poland and Its Fate, 1918–1939 (1998) excerpt and text search, comprehensive survey

Politics and diplomacy

- Cienciala, Anna M. "The Foreign Policy of Józef Pi£sudski and Józef Beck, 1926–1939: Misconceptions and Interpretations," The Polish Review (2011) 56#1 pp. 111–151 in JSTOR; earlier version

- Cienciala, Anna M. (1968), Poland the Western Powers, 1938–1939. A Study in the Interdependence of Eastern and Western Europe. PDF, Kansas U. Press.

- Cienciala, Anna M., and Titus Komarnicki (1984), From Versailles to Locarno, Keys to Polish Foreign Policy, 1919–1925 PDF, Kansas U. Press.

- Drzewieniecki, Walter M. "The Polish Army on the Eve of World War II," Polish Review (1981) 26#3 pp 54–64.

- Garlicki, Andrzej. Józef Piłsudski, 1867–1935 (New York: Scolar Press 1995), scholarly biography; one-vol version of 4 vol Polish edition

- Hetherington, Peter. Unvanquished: Joseph Pilsudski, Resurrected Poland, and the Struggle for Eastern Europe (2012) 752pp excerpt and text search

- Jędrzejewicz, W. Piłsudski. A Life for Poland (1982), scholarly biography

- Kantorosinski, Zbigniew. Emblem of Good Will: a Polish Declaration of Admiration and Friendship for the United States of America. Washington, DC: Library of Congress (1997)

- Polonsky, A. Politics in Independent Poland, 1921–1939: The Crisis of Constitutional Government (1972)

- Riekhoff, H. von. German-Polish Relations, 1918–1933 (Johns Hopkins University Press 1971)

- Rothschild, J. Piłsudski's Coup d'État (New York: Columbia University Press 1966)

- Wandycz, P. S. Polish Diplomacy 1914–1945: Aims and Achievements (1988)

- Wandycz, P. S. Soviet-Polish Relations, 1917–1921 (Harvard University Press 1969)

- Wandycz, P. S. The United States and Poland (1980)

- Zamoyski, Adam. Warsaw 1920: Lenin's Failed Conquest of Europe (2008) excerpt and text search

Social and economic topics

- Abramsky, C. et al. eds. The Jews in Poland (Oxford: Blackwell 1986)

- Blanke, R. Orphans of Versailles. The Germans in Western Poland, 1918–1939 (1993)

- Gutman, Y. et al. eds. The Jews of Poland Between Two World Wars (1989).

- Landau, Z. and Tomaszewski, J. The Polish Economy in the Twentieth Century (Routledge, 1985)

- Moklak, Jaroslaw. The Lemko Region in the Second Polish Republic: Political and Interdenominational Issues 1918–1939 (2013); covers Old Rusyns, Moscophiles and National Movement Activists, & the political role of the Greek Catholic and Orthodox Churches

- Olszewski, A. K. An Outline of Polish Art and Architecture, 1890–1980 (Warsaw: Interpress 1989.)

- Roszkowski, W. Landowners in Poland, 1918–1939 (Cambridge University Press, 1991)

- Staniewicz, Witold. "The Agrarian Problem in Poland between the Two World Wars," Slavonic and East European Review (1964) 43#100 pp. 23–33 in JSTOR

- Taylor, J. J. The Economic Development of Poland, 1919–1950 (Cornell University Press 1952)

- Wynot, E. D. Warsaw Between the Wars. Profile of the Capital City in a Developing Land, 1918–1939 (1983)

- Żółtowski, A. Border of Europe. A Study of the Polish Eastern Provinces (London: Hollis & Carter 1950)

- Eva Plach, "Dogs and dog breeding in interwar Poland," Canadian Slavonic Papers 60. no 3-4

Primary sources

- Small Statistical Yearbook, 1932 (Mały rocznik statystyczny 1932) complete text (in Polish)

- Small Statistical Yearbook, 1939 (Mały rocznik statystyczny 1939) complete text (in Polish)

Historiography

- Kenney, Padraic. "After the Blank Spots Are Filled: Recent Perspectives on Modern Poland", Journal of Modern History (2007) 79#1 pp 134–61, in JSTOR

- Polonsky, Antony. "The History of Inter-War Poland Today," Survey (1970) pp143–159.