Alexandrian text-type

The Alexandrian text-type is one of several text types found among New Testament manuscripts. It is the text type favored by textual critics and it is the basis for modern Bible translations. The name of the text type comes from Codex Alexandrinus, a manuscript of this type.

Over 5,800 New Testament manuscripts have been classified into four groups by text type. Besides Alexandrian, the other types are the Western, Caesarean, and Byzantine. Compared to these later text types, Alexandrian readings tend to be abrupt, use fewer words, show greater variation among the synoptic gospels, and have readings that are considered difficult. That is to say, later scribes tended to polish scripture and tried to improve its literary style. Glosses would occasionally be added as verses during the process of copying a Bible by hand. From the ninth century onward, most surviving manuscripts are of the Byzantine type.[1]

The King James Version and other Reformation-era Bibles are translated from Textus Receptus, a Greek text created by Erasmus and based on various manuscripts of the Byzantine type. In 1721, Richard Bentley outlined a project to create a revised Greek text based on Alexandrinus.[2] This project was completed by Karl Lachmann in 1850.[3] B.F. Westcott and F.J.A. Hort of Cambridge published a text based on Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus in 1881. Novum Testamentum Graece by Eberhard Nestle and Kurt Aland, now in its 28th edition, generally follows the text of Westcott and Hort.

Manuscripts

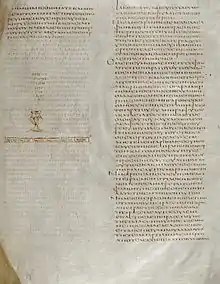

Up until the ninth century, Greek texts were written entirely in upper-case letters, referred to as uncials. During the ninth and tenth centuries, minuscules came to replace the older style. Most Greek uncial manuscripts were recopied in this period and their parchment leaves typically scraped clean for re-use. Consequently, surviving Greek New Testament manuscripts from before the ninth century are relatively rare, but nine (over half of the total that survive) witness a more-or-less pure Alexandrian text. These include the oldest near-complete manuscripts of the New Testament: Codex Vaticanus Graecus 1209 and Codex Sinaiticus (believed to date from the early fourth century).

A number of substantial papyrus manuscripts of portions of the New Testament survive from earlier still, and those that can be ascribed a text-type, such as 𝔓66 and 𝔓75 from the second to the third century, also tend to witness to the Alexandrian text.

The earliest Coptic versions of the Bible (into a Sahidic variety of the late second century) use the Alexandrian text as a Greek base; although other second and third century translations (into Latin and Syriac) tend rather to conform to the Western text-type. Although the overwhelming majority of later minuscule manuscripts conform to the Byzantine text-type; detailed study has, from time to time, identified individual minuscules that transmit the alternative Alexandrian text. Around 17 such manuscripts have been discovered so far and so the Alexandrian text-type is witnessed by around 30 surviving manuscripts, by no means all of which are associated with Egypt although in that area, Alexandrian witnesses are the most prevalent.

It was used by Clement of Alexandria,[4] Athanasius of Alexandria, and Cyril of Alexandria.

List of notable manuscripts represented Alexandrian text-type:

| Sign | Name | Date | Content |

| 𝔓45 | Chester Beatty I | 3rd | fragments of Gospels, Acts |

| 𝔓46 | Chester Beatty II | c. 200 | Pauline epistles |

| 𝔓47 | Chester Beatty III | 3rd | fragments of Revelation |

| 𝔓66 | Bodmer II | c. 200 | Gospel of John |

| 𝔓72 | Bodmer VII/VIII | 3rd/4th | Jude; 1-2 Peter |

| 𝔓75 | Bodmer XIV-XV | 3rd | Gospels of Luke and John |

| א | Codex Sinaiticus | 330-360 | NT |

| B | Codex Vaticanus | 325-350 | Matt. — Hbr 9, 14 |

| A | Codex Alexandrinus | c. 400 | (except Gospels) |

| C | Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus | 5th | (except Gospels) |

| Q | Codex Guelferbytanus B | 5th | fragments Luke — John |

| T | Codex Borgianus | 5th | fragments Luke — John |

| I | Codex Freerianus | 5th | Pauline epistles |

| Z | Codex Dublinensis | 6th | fragments of Matt. |

| L | Codex Regius | 8th | Gospels |

| W | Codex Washingtonianus | 5th | Luke 1:1–8:12; J 5:12–21:25 |

| 057 | Uncial 057 | 4/5th | Acts 3:5–6,10-12 |

| 0220 | Uncial 0220 | 6th | NT (except Rev.) |

| 33 | Minuscule 33 | 9th | Romans |

| 81 | Minuscule 81 | 1044 | Acts, Paul |

| 892 | Minuscule 892 | 9th | Gospels |

- Other manuscripts

Papyri: 𝔓1, 𝔓4, 𝔓5, 𝔓6, 𝔓8, 𝔓9, 𝔓10, 𝔓11, 𝔓12, 𝔓13, 𝔓14, 𝔓15, 𝔓16, 𝔓17, 𝔓18, 𝔓19, 𝔓20, 𝔓22, 𝔓23, 𝔓24, 𝔓26, 𝔓27, 𝔓28, 𝔓29, 𝔓30, 𝔓31, 𝔓32, 𝔓33, 𝔓34, 𝔓35, 𝔓37, 𝔓39, 𝔓40, 𝔓43, 𝔓44, 𝔓49, 𝔓51, 𝔓53, 𝔓55, 𝔓56, 𝔓57, 𝔓61, 𝔓62, 𝔓64, 𝔓65, 𝔓70, 𝔓71, 𝔓74, 𝔓77, 𝔓78, 𝔓79, 𝔓80 (?), 𝔓81, 𝔓82, 𝔓85 (?), 𝔓86, 𝔓87, 𝔓90, 𝔓91, 𝔓92, 𝔓95, 𝔓100, 𝔓104, 𝔓106, 𝔓107, 𝔓108, 𝔓110, 𝔓111, 𝔓115, 𝔓122.

Uncials: Codex Coislinianus, Porphyrianus (except Acts, Rev), Dublinensis, Sangallensis (only in Mark), Zacynthius, Athous Lavrensis (in Mark and Cath. epistles), Vaticanus 2061, 059, 068, 071, 073, 076, 077, 081, 083, 085, 087, 088, 089, 091, 093 (except Acts), 094, 096, 098, 0101, 0102, 0108, 0111, 0114, 0129, 0142, 0155, 0156, 0162, 0167, 0172, 0173, 0175, 0181, 0183, 0184, 0185, 0189, 0201, 0204, 0205, 0207, 0223, 0225, 0232, 0234, 0240, 0243, 0244, 0245, 0247, 0254, 0270, 0271, 0274.

Minuscules: 20, 94, 104 (Epistles), 157, 164, 215, 241, 254, 256 (Paul), 322, 323, 326, 376, 383, 442, 579 (except Matthew), 614, 718, 850, 1006, 1175, 1241 (except Acts), 1243, 1292 (Cath.), 1342 (Mark), 1506 (Paul), 1611, 1739, 1841, 1852, 1908, 2040, 2053, 2062, 2298, 2344 (CE, Rev), 2351, 2427, 2464.[5]

According to the present critics codices 𝔓75 and B are the best Alexandrian witnesses, which present the pure Alexandrian text. All other witnesses are classified according to whether they preserve the excellent 𝔓75-B line of text. With the primary Alexandrian witnesses are included 𝔓66 and citations of Origen. With the secondary witnesses are included manuscripts C, L, 33, and the writings of Didymus the Blind.[6]

Characteristics

All extant manuscripts of all text-types are at least 85% identical and most of the variations are not translatable into English, such as word order or spelling. When compared to witnesses of the Western text-type, Alexandrian readings tend to be shorter and are commonly regarded as having a lower tendency to expand or paraphrase. Some of the manuscripts representing the Alexandrian text-type have the Byzantine corrections made by later hands (Papyrus 66, Codex Sinaiticus, Codex Ephraemi, Codex Regius, and Codex Sangallensis).[7] When compared to witnesses of the Byzantine text type, Alexandrian manuscripts tend:

- to have a larger number of abrupt readings, such as the shorter ending of the Gospel of Mark, which finishes in the Alexandrian text at Mark 16:8 (".. for they were afraid.") omitting verses Mark 16:9-20; Matthew 16:2b–3, John 5:4; John 7:53-8:11;

- Omitted verses: Matt 12:47; 17:21; 18:11; Mark 9:44.46; 11:26; 15:28; Luke 17:36; Acts 8:37; 15:34; 24:7; 28:29.[8]

- In Matthew 15:6 omitted η την μητερα (αυτου) (or (his) mother): א B D copsa;[9]

- In Mark 10:7 omitted phrase και προσκολληθησεται προς την γυναικα αυτου (and be joined to his wife), in codices Sinaiticus, Vaticanus, Athous Lavrensis, 892, ℓ 48, syrs, goth.[10]

- Mark 10:37 αριστερων (left) instead of ευωνυμων (left), in phrase εξ αριστερων (B Δ 892v.l.) or σου εξ αριστερων (L Ψ 892*);[11]

- In Luke 11:4 phrase αλλα ρυσαι ημας απο του πονηρου (but deliver us from evil) omitted. Omission is supported by the manuscripts: Sinaiticus, B, L, f1, 700, vg, syrs, copsa, bo, arm, geo.[12]

- In Luke 9:55-56 it has only στραφεις δε επετιμησεν αυτοις (but He turned and rebuked them): 𝔓45 𝔓75 א B C L W X Δ Ξ Ψ 28 33 565 892 1009 1010 1071 Byzpt Lect

- to display more variations between parallel synoptic passages, as in the Lukan version of the Lord's Prayer (Luke 11:2), which in the Alexandrian text opens "Father.. ", whereas the Byzantine text reads (as in the parallel Matthew 6:9) "Our Father in heaven.. ";

- to have a higher proportion of "difficult" readings, as in Matthew 24:36, which reads in the Alexandrian text "But of that day and hour no one knows, not even the angels of heaven, nor the Son, but the Father only"; whereas the Byzantine text omits the phrase "nor the Son", thereby avoiding the implication that Jesus lacked full divine foreknowledge. Another difficult reading: Luke 4:44.

The above comparisons are tendencies, rather than consistent differences. There are a number of passages in the Gospel of Luke in which the Western text-type witnesses a shorter text, the Western non-interpolations. Also, there are a number of readings where the Byzantine text displays variation between synoptic passages, that is not found in either the Western or Alexandrian texts, as in the rendering into Greek of the Aramaic last words of Jesus, which are reported in the Byzantine text as "Eloi, Eloi.." in Mark 15:34, but as "Eli, Eli.." in Matthew 27:46.

Evaluations of text-types

Most textual critics of the New Testament favor the Alexandrian text-type as the closest representative of the autographs for many reasons. One reason is that Alexandrian manuscripts are the oldest found; some of the earliest Church Fathers used readings found in the Alexandrian text. Another is that the Alexandrian readings are adjudged more often to be the ones that can best explain the origin of all the variant readings found in other text-types.

Nevertheless, there are some dissenting voices to this consensus. A few textual critics, especially those in France, argue that the Western text-type, an old text from which the Vetus Latina or Old Latin versions of the New Testament are derived, is closer to the originals.

In the United States, some critics have a dissenting view that prefers the Byzantine text-type, such as Maurice A. Robinson and William Grover Pierpont. They assert that Egypt, almost alone, offers optimal climatic conditions favoring preservation of ancient manuscripts while, on the other hand, the papyri used in the east (Asia Minor and Greece) would not have survived due to the unfavourable climatic conditions. Thus, it is not surprising that ancient Biblical manuscripts that are found would come mostly from the Alexandrian geographical area and not from the Byzantine geographical area.

The argument for the authoritative nature of the latter is that the much greater number of Byzantine manuscripts copied in later centuries, in detriment to the Alexandrian manuscripts, indicates a superior understanding by scribes of those being closer to the autographs. Eldon Jay Epp argued that the manuscripts circulated in the Roman world and many documents from other parts of the Roman Empire were found in Egypt since the late 19th century.[13]

The evidence of the papyri suggests that, in Egypt, at least, very different manuscript readings co-existed in the same area in the early Christian period. Thus, whereas the early 3rd century papyrus 𝔓75 witnesses a text in Luke and John that is very close to that found a century later in the Codex Vaticanus, the nearly contemporary 𝔓66 has a much freer text of John; with many unique variants; and others that are now considered distinctive to the Western and Byzantine text-types, albeit that the bulk of readings are Alexandrian. Most modern text critics therefore do not regard any one text-type as deriving in direct succession from autograph manuscripts, but rather, as the fruit of local exercises to compile the best New Testament text from a manuscript tradition that already displayed wide variations.

History of research

Griesbach produced a list of nine manuscripts which represent the Alexandrian text: C, L, K, 1, 13, 33, 69, 106, and 118.[14] Codex Vaticanus was not on this list. In 1796, in the second edition of his Greek New Testament, Griesbach added Codex Vaticanus as witness to the Alexandrian text in Mark, Luke, and John. He still thought that the first half of Matthew represents the Western text-type.[15]

Johann Leonhard Hug (1765–1846) suggested that the Alexandrian recension was to be dated about the middle of the 3rd century, and it was the purification of a wild text, which was similar to the text of Codex Bezae. In result of this recension interpolations were removed and some grammar refinements were made. The result was the text of the codices B, C, L, and the text of Athanasius and Cyril of Alexandria.[16][17]

Starting with Karl Lachmann (1850), manuscripts of the Alexandrian text-type have been the most influential in modern, critical editions of the Greek New Testament, achieving widespread acceptance in the text of Westcott & Hort (1881), and culminating in the United Bible Society 4th edition and Nestle-Aland 27th edition of the New Testament.

Until the publication of the Introduction of Westcott and Hort in 1881 remained opinion that the Alexandrian text is represented by codices B, C, L. The Alexandrian text is one of the three ante-Nicene texts of the New Testament (Neutral and Western). The text of the Codex Vaticanus stays in closest affinity to the Neutral Text.

After discovering the manuscripts 𝔓66 and 𝔓75 the Neutral text and Alexandrian text were unified.[18]

See also

References

- Anderson, Gerry, Ancient New Testament Manuscripts Understanding Text-Types"

- Bentley, Richard, Dr. Richard Bentley's proposals for printing a new edition of the Greek Testament and St. Hierom's Latin version, London, 1721.

- Lachmann, Karl, Novum testamentum graece et latine, Cambridge Univ Press, 2010. Originally published in two volumes in 1842 and 1850.

- P. M. Barnard, The Quotations of Clement of Alexandria from the Four Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles, Texts & Studies, vol. 5, no. 4 (Cambridge, 1899).

- David Alan Black, New Testament Textual Criticism, Baker Books, 2006, p. 64.

- Bruce M. Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption and Restoration, Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 278.

- E. A. Button, An Atlas of Textual Criticism, Cambridge, 1911, p. 13.

- Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft: Stuttgart 2001), pp. 315, 388, 434, 444.

- NA26, p. 41.

- UBS3, p. 164.

- NA26, p. 124.

- UBS3, p. 256.

- Eldon Jay Epp, A Dynamic View of Testual Transmission, in: Studies & Documents 1993, p. 280

- J. J. Griesbach, Novum Testamentum Graecum, vol. I (Halle, 1777), prolegomena.

- J. J. Griesbach, Novum Testamentum Graecum, 2 editio (Halae, 1796), prolegomena, p. LXXXI. See Edition from 1809 (London)

- J. L. Hug, Einleitung in die Schriften des Neuen Testaments (Stuttgart 1808), 2nd edition from Stuttgart-Tübingen 1847, p. 168 ff.

- John Leonard Hug, Writings of the New Testament, translated by Daniel Guildford Wait (London 1827), p. 198 ff.

- Gordon D. Fee, P75, P66, and Origen: THe Myth of Early Textual Recension in Alexandria, in: E. J. Epp & G. D. Fee, Studies in the Theory & Method of NT Textual Criticism, Wm. Eerdmans (1993), pp. 247-273.

Further reading

- Bruce M. Metzger & Bart D. Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption and Restoration, Oxford University Press, 2005, pp. 277–278.

- Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament: A Companion Volume to the United Bible Societies' Greek New Testament, 1994, United Bible Societies, London & New York, pp. 5*, 15*.

- Carlo Maria Martini, La Parola di Dio Alle Origini della Chiesa, (Rome: Bibl. Inst. Pr. 1980), pp. 153–180.

- Gordon D. Fee, P75, P66, and Origen: The Myth of Early Textual Recension in Alexandria, in: Studies in the Theory and Method of New Testament Textual Criticism, vol. 45, Wm. Eerdmans 1993, pp. 247–273.