Papyrus 46

Papyrus 46 (in the Gregory-Aland numbering), scribal abbreviation 46, is an early Greek New Testament manuscript written on papyrus, with its 'most probable date' between 175 and 225.[1] Some leaves are part of the Chester Beatty Biblical Papyri ('CB' in the table below), and others are in the University of Michigan Papyrus Collection ('Mich.' in the table below).[2]

| New Testament manuscript | |

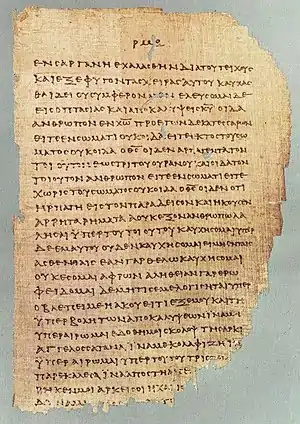

A folio from 46 containing 2 Corinthians 11:33–12:9. As with other folios of the manuscript, text is lacunose at the bottom. | |

| Name | P. Chester Beatty II; Ann Arbor, Univ. of Michigan, Inv. 6238 |

|---|---|

| Sign | 46 |

| Text | Pauline epistles |

| Date | c. 175–225 |

| Script | Greek |

| Now at | Dublin, University of Michigan |

| Cite | Sanders, A Third Century Papyrus Codex of the Epistles of Paul |

| Size | 28 cm by 16 cm |

| Type | Alexandrian text-type |

| Category | I |

| Note | Affinity with Minuscule 1739 |

Contents

46 contains most of the Pauline epistles, though with some folios missing. It contains (in order) "the last eight chapters of Romans; all of Hebrews; virtually all of 1–2 Corinthians; all of Ephesians, Galatians, Philippians, Colossians; and two chapters of 1 Thessalonians. All of the leaves have lost some lines at the bottom through deterioration."[3]

| Folio | Contents | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 1–7 | Romans 1:1–5:17 | Missing |

| 8 | Rom 5:17–6:14 | CB |

| 9-10 | Rom 6:14–8:15 | Missing |

| 11–15 | Rom 8:15–11:35 | CB |

| 16–17 | Rom 11:35–14:8 | Mich. |

| 18 (fragment) | Rom 14:9–15:11 | CB |

| 19–28 | Rom 15:11–Hebrews 8:8 | Mich. |

| 29 | Heb 8:9–9:10 | CB |

| 30 | Heb 9:10–26 | Mich. |

| 31–39 | Heb 9:26–1 Corinthians 2:3 | CB |

| 40 | 1 Cor 2:3–3:5 | Mich. |

| 41–69 | 1 Cor 3:6–2 Corinthians 9:7 | CB |

| 70–85 | 2 Cor 9:7–end, Ephesians, Galatians 1:1–6:10 | Mich. |

| 86–94 | Gal 6:10–end, Philippians, Colossians, 1 Thessalonians 1:1–2:3 | CB |

| 95–96 | 1 Thess 2:3–5:5 | Missing |

| 97 (fragment) | 1 Thess 5:5, 23–28 | CB |

| 98–104 | Thought to be 1 Thess 5:28–2 Thessalonians, and possibly Philemon; as for 1–2 Timothy, and Titus (see below) | Missing |

Dimensions

Folio size is approximately 28 by 16 centimetres (11.0 in × 6.3 in) with a single column of text averaging 11.5 centimetres (4.5 in). There are between 26 and 32 lines (rows) of text per page, although both the width of the rows and the number of rows per page increase progressively. Rows of text at the bottom of each page are damaged (lacunose), with between 1–2 lines lacunose in the first quarter of the MS, 2–3 lines lacunose in the central half, and up to seven lines lacunose in the final quarter. Unlike virtually every other ancient manuscript of any type known to exist, P46 contains the scribe's colophon on some pages, as well as page numbers of the codex, though many pages lack both due to damage.[4]

Missing contents

The manuscript was initially examined in micro graph form by renowned scholar Frederic G. Kenyon. Kenyon attempted to ascertain the tendencies of the scribe of P46, the number of lines per page, and letters per line to estimate the contents of the missing pages. This data would have been used by the scribe to calculate how much writing material was needed, as well as the fee the scribe collected (scribes charged by the line for their services).[4]

From the page numbers on existing pages, we know that seven leaves have been lost from the beginning of the codex, which accords perfectly with the length of the missing portion of Romans, which they undoubtedly contained. Since the codex is formed from a stack of papyrus sheets folded in the middle, magazine-style, what is lost is the outer seven sheets, containing the first and last seven leaves of the codex.

The contents of the seven missing leaves from the end is uncertain as they are lost. Kenyon calculated[5] that 2 Thessalonians would require two leaves, leaving only five remaining leaves (10 pages) for the remaining canonical Pauline literature — 1 Timothy (estimated 8.25 pages), 2 Timothy (6 pages), Titus (3.5 pages) and Philemon (1.5 pages) — totaling ten required leaves (19.25 pages). Thus Kenyon concluded that P46 did not include the pastorals. This view was dominant for several decades.

However, recent research has called into question Kenyon's analysis. Firstly, Kenyon did not account for the fact that the scribe's average letter per page was increasing deeper into the Codex. There are half again as many letters per page in the last leaves than in the middle leaves. But this is partially due to the fact that the outer leaves are wider than the inner leaves. Nevertheless, there are more letters in the back outer leaves than the front outer leaves, showing that at least some compression did take place. And this seems to suggest that the scribe was aware of the problem he had created for including the pastorals and he began to compensate upon realizing his mistake.[6]

Secondly, the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts (CSNTM) was able to take high resolution images of the original Codex leaves. Upon examining the new images, the CSNTM determined that Kenyon's lower quality microfilm was slightly skewed, leading Kenyon to over estimate how much writing space the scribe was using to complete his work. At least three of Kenyon's measurements were off by 3 mm, and one was off by 5 mm.[4] This measuring error then was compounded over the rest of the codex causing Kenyon to then underestimate how much space the scribe needed to complete his work. Daniel B. Wallace, only performing measurements on a few leaves, noted that further research was needed.

Interpunction

Throughout Romans, Hebrews and the latter chapters of 1 Corinthians are found small and thick strokes or dots, usually agreed to be from the hand of a reader rather than the producer of the manuscript since the ink is always much paler than that of the text itself.[7] They appear to mark sense divisions (similar to verse numbering found in Bibles) and are also found in portions of 45, possibly evidence of reading in the community which held both codices. Edgar Ebojo made a case that these "reading marks" with or without space-intervals were an aid to readers, most likely in a liturgical context.[8]

Nomina Sacra

46 uses an extensive and well-developed system of nomina sacra.[1] Griffin argued against Kim, in part, that such an extensive usage of the nomina sacra system nearly eliminates any possibility of the manuscript dating to the 1st century. He admitted, however, that Kim's dating cannot be ruled out on this basis alone, since the exact provenance of the nomina sacra system itself is not well-established.[1]

On the other hand, Comfort (preferring a date c. 150–175) notes indications that the scribe's exemplar made limited use of nomina sacra or none at all.[9]:131–139, 223, 231–238 In several instances, the word for Spirit is written out in full where the context should require a nomen sacrum, suggesting that the scribe was rendering nomina sacra where appropriate for the meaning but struggling with Spirit versus spirit without guidance from the exemplar. Further, the text inconsistently uses either the short or the long contracted forms of Christ.

Text

The Greek text of the codex is a representative of the Alexandrian text-type. Kurt Aland placed it in Category I.[2]

In Romans 16:15 it has singular reading Βηρεα και Αουλιαν for Ιουλιαν, Νηρεα.[10]

In 1 Corinthians 2:1 it reads μυστηριον along with א, Α, C, 88, 436, ita,r, syrp, copbo. Other manuscripts read μαρτυριον or σωτηριον.[11]

In 1 Corinthians 2:4 it reads πειθοις σοφιας (plausible wisdom) for πειθοις σοφιας λογοις (plausible words of wisdom), the reading is supported only by Codex Boernerianus (Greek text).[11]

In 1 Corinthians 7:5 it reads τη προσευχη (prayer) along with 11, א*, A, B, C, D, F, G, P, Ψ, 6, 33, 81, 104, 181, 629, 630, 1739, 1877, 1881, 1962, it vg, cop, arm, eth. Other manuscripts read τη νηστεια και τη προσευχη (fasting and prayer) τη προσευχη και νηστεια (prayer and fasting).[12][13]

In 1 Corinthians 12:9 it reads εν τω πνευματι for εν τω ενι πνευματι.[14]

In 1 Corinthians 15:47 it has singular reading reads δευτερος ανθρωπος πνευματικος for δευτερος ανθρωπος (א*, B, C, D, F, G, 0243, 33, 1739, it, vg, copbo eth); or δευτερος ανθρωπος ο κυριος (אc, A, Dc, K, P, Ψ, 81, 104, 181, 326, 330, 436, 451, 614, 629, 1241, 1739mg, 1877, 1881, 1984, 1985, 2127, 2492, 2495, Byz, Lect).[15]

In 2 Corinthians 1:10 it reads τηλικουτων θανατων, along with 630, 1739c, itd,e, syrp,h, goth; majority reads τηλικουτου θανατου.[16]

Galatians 6:2 — αναπληρωσατε ] αποπληρωσετε[17]

Ephesians 4:16 — κατ ενεργειας ] και ενεργειας.[18]

Ephesians 6:12 — αρχας προς τας εξουσιας ] μεθοδιας[19]

However, it significantly also contains a non-Alexandrian reading in the following location, for which it is an important witness:

Romans 8:28 - παντα συνεργει ό θεος εις αγαθον[20] (God always works together in good).

Provenance

The provenance of the papyrus is unknown, although it was probably originally discovered in the ruins of an early Christian church or monastery.[21][22] Following the discovery in Cairo, the manuscript was broken up by the dealer. Ten leaves were purchased by Chester Beatty in 1930; the University of Michigan acquired six in 1931 and 24 in 1933. Beatty purchased 46 more in 1935, and his acquisitions now form part of the Chester Beatty Biblical Papyri, eleven codices of biblical material.

Date

As with all manuscripts dated solely by palaeography, the dating of 46 is uncertain. The first editor of parts of the papyrus, H. A. Sanders, proposed a date possibly as late as the second half of the 3rd century.[23] F. G. Kenyon, editor of the complete editio princeps, preferred a date in the first half of the 3rd century.[24] The manuscript is now sometimes dated to about 200.[25] Young Kyu Kim[26] has argued for an exceptionally early date of c. 80.[27] Kim's dating has been widely rejected.[28][29][9]:180ff.[30] Griffin critiqued and disputed Kim's dating,[1] placing the 'most probable date' between 175–225, with a '95% confidence interval' for a date between 150–250.[31]

Comfort and Barrett[32] have claimed that 46 shares affinities with the following:

- P. Oxy. 8 (assigned late 1st or early 2nd century),

- P. Oxy. 841 (the second hand, which cannot be dated later than 125–150),

- P. Oxy. 1622 (dated with confidence to pre-148, probably during the reign of Hadrian (117–138), because of the documentary text on the verso),

- P. Oxy. 2337 (assigned to the late 1st century),

- P. Oxy. 3721 (assigned to the second half of the 2nd century),

- P. Rylands III 550 (assigned to the 2nd century), and

- P. Berol. 9810 (early 2nd century).

This, they conclude, points to a date during the middle of the 2nd century for 46.

See also

- List of New Testament papyri

- Collections of papyri

- Chester Beatty Papyri

- University of Michigan Papyrus Collection

References

- Griffin, Bruce W. (1996), "The Paleographical Dating of P-46"

- Aland, Kurt; Aland, Barbara (1995). The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism. Erroll F. Rhodes (trans.). Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-8028-4098-1.

- Michael Marlowe, Papyrus 46

- Wallace, Dan (8 June 2013). "Some Notes on the Earliest Manuscript of Paul's Letters". Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts. Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- F. G. Kenyon, The Chester Beatty Biblical Papyri. III.1 Pauline Epistles and Revelation. Text, London: E. Walker, 1934

- Duff, Jeremy (1998). "46 and the pastorals: A Misleading Consensus?". New Testament Studies. University of Cambridge: Cambridge Core. 44 (4): 578–590. doi:10.1017/S0028688500016738. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- H. A. Sanders, A Third Century Papyrus Codex of the Epistles of Paul, (Ann Arbor, 1935), 17

- Edgar Ebojo, "When Nonsense Makes Sense: Scribal Habits in the Space-Intervals, Sense Pauses, and other Visual Features in P46," The Bible Translator August 2013 64: 128–150

- Comfort, Philip W. (2005). Encountering the Manuscripts: An Introduction to New Testament Paleography & Textual Criticism. Nashville: Broadman & Holman. ISBN 978-1-4336-7067-1.

- UBS3, p. 575.

- UBS3, p. 581.

- NA26, p. 450.

- UBS3, p. 591.

- UBS3, p. 605.

- UBS3, p. 616.

- UBS3, p. 622.

- UBS3, p. 661.

- NA26, p. 509.

- NA26, p. 513.

- UBS3, p.551.

- F. G. Kenyon, The Chester Beatty Biblical Papyri: I. General Introduction, (London: E. Walker), 1933, 5

- C.H. Roberts, Manuscript, Society and Belief in Early Christian Egypt, p. 7

- H. A. Sanders, A Third-Century Papyrus Codex of the Epistles of Paul (Ann Arbor, 1935), pp. 13–15.

- F. G. Kenyon, The Chester Beatty Biblical Papyri, part 3 (London, 1936), xiv–xv.

- Willker, Wieland "Complete List of Greek NT Papyri" Archived 2014-03-12 at the Wayback Machine Last Update: 17.04.2008. Retrieved 26/08/08.

- A thorough search of Google Books and the internet found nothing else from or about this author, except a 2015 thesis implying he was a professor at Calvin Theological Seminary.

- Kim, YK (1988), "Palaeographical Dating of P46 to the Later First Century," Biblica, 69, p. 248

- Royse, J.R. (2007). Scribal Habits in Early Greek New Testament Papyri. New Testament Tools, Studies and Documents. Brill. p. 199ff. ISBN 978-90-474-2366-9. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- Barker, Don (5 September 2011). "The Dating of New Testament Papyri". New Testament Studies. Cambridge University Press (CUP). 57 (4): 578f. doi:10.1017/s0028688511000129. ISSN 0028-6885.

- Evans, C.A. (2011). The World of Jesus and the Early Church: Identity and Interpretation in Early Communities of Faith. Hendrickson Publishers. p. 207. ISBN 978-1-59856-825-7. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- See email from Griffin added in 2005 to Griffin's 1996 paper.

- Comfort, Philip W. and Barrett, David P (2001) 'The Text of the Earliest New Testament Greek Manuscripts', Wheaton, Illinois: Tyndale House Publishers Incorporated, pp. 204–206.

Further reading

- Comfort, Philip W.; David P. Barrett (2001). The Text of the Earliest New Testament Greek Manuscripts. Wheaton, Illinois: Tyndale House Publishers. pp. 203–354. ISBN 978-0-8423-5265-9.

External links

- Official WWW of Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, concerning P46

- Robert B. Waltz. 'NT Manuscripts: Papyri, Papyri 46.'

- Leaves of 46 at the University of Michigan (with images in TIFF)

- Reading the Papyri: 46 from the University of Michigan Papyrus Collection

- At Evangelical Textual Criticism

- Klaus Wachtel, Klaus Witte, Das Neue Testament auf Papyrus: Gal., Eph., Phil., Kol., 1. u. 2. Thess., 1. u. 2 Tim., Tit., Phlm., Hebr, Walter de Gruyter, 1994, pp. L-LII.

- "Liste Handschriften". Münster: Institute for New Testament Textual Research. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- Tricky NT Textual Issues: Codex P46