Altstadt (Frankfurt am Main)

The Altstadt (old town) is a city district of Frankfurt am Main, Germany. It is part of the Ortsbezirk Innenstadt I.

Altstadt | |

|---|---|

Coat of arms | |

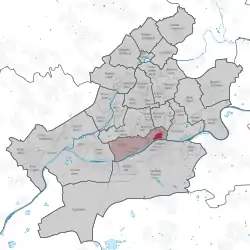

Location of the Altstadt (red) and the Ortsbezirk Innenstadt I (light red) within Frankfurt am Main  | |

Altstadt  Altstadt | |

| Coordinates: 50°06′49″N 08°41′04″E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Hesse |

| Admin. region | Darmstadt |

| District | Urban district |

| Town | Frankfurt am Main |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.477 km2 (0.184 sq mi) |

| Population (2007-12-31) | |

| • Total | 3,473 |

| • Density | 7,300/km2 (19,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal codes | 60311 |

| Dialling codes | 069 |

| Vehicle registration | F |

| Website | www.frankfurt.de |

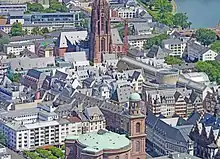

The Altstadt is located on the northern Main river bank. It is completely surrounded by the Innenstadt district, Frankfurt's present-day city centre. On the opposite side of the Main is the district of Sachsenhausen.

The historic old town of Frankfurt was one of the largest half-timbered towns in Germany until the extensive destruction in World War II with its around 1250 half-timbered houses, most of which date from the Middle Ages.[1] It was one of the most important tourist attractions for Germany. The historic old town was largely destroyed by the air raids on Frankfurt am Main in 1944. The streets and the entire district are predominantly characterized by quickly and easily erected buildings from the 1950s and 60s. A handful of the most important historic buildings, churches and squares were restored or reconstructed, especially around the main square, the Römerberg.

However, from 2012 to 2018, a small section of the old town was reconstructed. A construction project known as the Dom-Römer project, restored a small section of the old town between the Imperial Cathedral and the Römer town hall, following a decision by the city council in 2007. A few former streets and squares that once stood in the area were rebuilt, most notably the historical coronation route of German emperors through the old town from the cathedral.[2]

General information

Surface and Population

The Altstadt is the smallest district of Frankfurt, covering less than half a square kilometre. The area is completely built-up with the only open spaces being accounted for by the Main and the river bank, the streets, squares and backyards. The construction descends predominantly from the reconstruction phase of the post-war era, aside from which there are numerous historical buildings partly reconstructed after their destruction in the Second World War.

Approximately 3,400 people reside in the Altstadt of which an estimated 32% are of foreign origin. This is above the ratio of the entire town, but far under that of the other town quarters. The adjacent Neustadt, for example, is home to 44% non-German inhabitants.

Museums and theatres dominate the western part of Altstadt and service jobs are a major part of the economy, especially along Weißfrauenstraße and Berliner Straße. The centre of Altstadt is a hot spot for the city's tourism industry, with tours around the most meaningful sights such as Paulskirche, Römer, and the Frankfurt Cathedral, as well as being the seat of the city's administrative branch. In the north of the district the retail industry is well represented, particularly in Neue Kräme and Töngesgasse. Residential flats are found in the east in an area which also contains most of Frankfurt's art trade (Braubachstraße and Fahrgasse).

Economy

By far the largest employer in the old part of the city is the city's administration. Even today the Altstadt is the political centre of the city. The city council, magistrates and a considerable part of the city departments are located in Römer square, either in the town hall itself or in the surrounding properties.

In the past years, two other important facilities abandoned the Altstadt and the city as a whole: the German Federal Court of Auditors of Berliner Straße which was relocated to Bonn, and the headquarters of Degussa from Weißfrauenstraße which moved to Düsseldorf. While the monument-listed building of the German Federal Court of Auditors is currently being redeveloped, the former Degussa building had been torn down, and the area has been redeveloped into flats and offices.

Other important factors of the economy are the retail and tourist industries. Although there were still numerous small industrial businesses in the narrow lanes up until the Second World War, the retail sector now outweighs all other types of business. Particularly in Neue Kräme and Töngesgasse many niche eateries can be found. In Berliner Straße there a numerous shops specialised on Asian tourists who come to the city for extensive shopping trips. The Fahrgasse and the quarter around the Weckmarkt at the cathedral form the traditional centre for antique dealers in Frankfurt.

Traffic

The Altstadt is remarkably open because of its attachment to the suburban traffic network. The underground station "Dom/Römer", opened in 1974, connected the historical core of the city to the Underground lines 4 and 5. The building of the track and the station in the years 1968–74 represented a special technical challenge. The underground junction of Willy-Brandt-Platz connects parts of the Altstadt, the rapid-transit system of Hauptwache and Konstablerwache to the north.

Tram lines 11 and 12 operate along the central thoroughfare of Bethmannstrasse-Braubachstrasse-Battonnstrasse. At the start of the 20th century, two tram lines were laid through Altstadt, the first—the so-called Dienstmädchenlinie (Handmaid's line)—from the Zeil past the Trierischen Hof (hotel) in the direction of the cathedral, the other along the newly laid Brauchbachstrasse in an east to west direction. While the Dienstmädchen line was never successful and had been shut down after the First World War, the east–west line remained and is now known as the Altstadtstrecke. In 1986 its redundant status was brought to an end due to the intervention of the district president in Darmstadt. In the meantime the Altstadtstrecke gained a firm place in local public passenger transport, especially with the Ebbelwei-express, which serves an exclusive tourist route.

Three bridges lead out of the Altstadt over the Main; Alte Brücke, Eiserner Steg and Untermainbrücke.

The Mainkai (Main quay), as the name suggests, stands on the oldest harbour in the city. Ships are still moored there today; however, these only serve tourists along the Main and the Rhine. Ships transporting goods are instead found, as in the city's early days, in the main harbours of Frankfurt.

Aeral view of the old town

Aeral view of the old town The Römerberg is the central square of the Altstadt

The Römerberg is the central square of the Altstadt Paulskirche

Paulskirche Metro station Dom/Römer

Metro station Dom/Römer

History

The old town in pre-medieval times

The city's founding legend names Charlemagne as the city's founder, which corresponds to the oldest surviving documentary mention on the occasion of a donation to the St. Emmeran monastery near Regensburg on February 22, 794, but not the archaeological finding. Accordingly, the Royal Palatinate Frankfurt was only created under the son of the legendary founder, Ludwig the Pious, between 815 and 822.

According to the current state of research, the core settlement was to be located on the Samstagsberg.

Archaeological findings on the Römerberg, and most recently in the area of the Old Nikolaikirche, showed slight remains of a wall to be considered Carolingian, which would presumably surround the settlement on the Samstagsberg and, in a continued process, would also satisfactorily explain the striking rounding of the plots on the former Goldhutgasse. If one follows this assumption, the wall in the south was roughly limited by the course of the later Bendergasse, the northern and western extent can only be guessed at. Overall, however, there is a typical, ring-like fortification, the former row of buildings in the eastern part until the destruction of the Second World War was reflected by the parcels within their former borders.

In the 9th century the Palatinate Franconofurd developed into one of the political centres of the eastern Franconian empire. Around the year 1000, the old town area was fortified under the Ottonian dynasty with a wider wall ring. It is unclear whether the core settlement had already expanded beyond the Carolingian wall at this time. Recent publications cautiously point out that at the earliest from the middle of the 10th century there was a very long transition from the post house to the half-timbered building with stone foundations, the scanty findings actually point to a slow expansion of the city limits at that time.

After the Carolingian Palatinate probably ended with a fire between 1017 and 1027 and the rulers of the Salians showed little interest in the city, the settlement activity only expanded again significantly with the active support of the Staufer in the 12th century. King Conrad III had a royal castle built on the Main in the middle of the 12th century with the Saalhof, which is still preserved in parts from this period . A little later, the urban area was enclosed with a wall named after the Swabian noble family, the course of which is still clearly visible in the shape of the city due to small remains above ground.

Until the destruction of the Second World War, the street map was still recognisable from this period. This is clear from an impression of the street network from the early 14th century which shows that the Altstadt had already taken the form it would take for centuries.

Most of the church and monastery foundations and the construction of the most important public buildings, most recently the town hall through reconstruction in 1405, fell into this first political and economic heyday through the acquisition of numerous imperial privileges.

The emergence of the Altstadt in the Middle Ages

The Altstadt is on the right bank of the Main on the outer edge of a soft bend in the river. Here was the ford which gave the city its name. In the place of today's cathedral was a raised, flood proof plateau, the so-called Dominsel (cathedral island). At the time it was protected in the north by a branch of the main, the Brauchbach. This island represents the historic origin of the city and was presumably settled in the Neolithic era. Archaeological excavations in the 1950s and 1990s brought to light the remainders of a Roman military camp, an Alamanni property yard and a Merovingian king's court. Legends of the city's founding name Karl the Great as the city's founder, which corresponds to the oldest known documents (Frankfurt council, 794), but contradicts the archaeological findings.

The area of the city initially grew out west around the start of the 2nd millennium (around the area west of today's Römerberg). One of the oldest city walls, the Staufenmauer, was erected connecting the area of these two expansions and equated to today's Altstadt. The adjacent district of the Innenstadt equated to the historic Neustadt, an expansion in 1333. On the border between the two was where the Jewish ghetto of the Judengasse was established.

The Altstadt in the Medieval Period

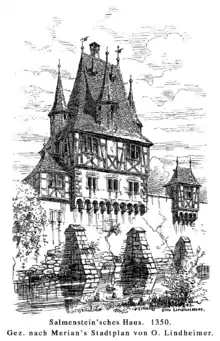

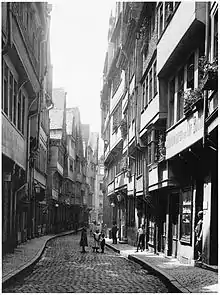

Over the course of the centuries, the population of the city always continued to increase, whereby the population density of the Altstadt continuously increased. The buildings finally had up to five full storeys and (due to the usual, very steep roofs) several attics. Each floor protruded outwards in excess of the one beneath it so the inhabitants of the highest floors could reach out and touch the hand of the person living on the other side of the alley.

The old town began to display a clear structure with three north–south axis identifiable: in the west the Kornmarkt ran between Bockenheimer Gate (to the church later erected and named Katharinenpforte) and Leonhardstor (tower) next to Leonhardskirche (church) on the Main. In the middle of the district Neue Kräme connected the two largest squares of the Altstadt, Liebfrauenberg to Römerberg and further towards the south lying Fahrtor on the bank of the Main and the harbour there. The Fahrgasse ran east of the cathedral from Bornheimer Gate near today's Konstablerwache to the Main bridge. It was one of the most busy streets for Frankfurt traffic in the 20th century.

The majority of Frankfurt's inhabitants lived in the densely populated Altstadt, while the Neustadt remained characteristically suburban until far into the 18th century with loose land development and agriculture featuring prominently in contrast with Altstadt. The city in general was divided into fourteen parts after the Fettmilch Rising of 1614. Seven of these formed the relatively small Altstadt, five belonged to the Neustadt (which made it three times bigger than the Altstadt) and two for Sachsenhausen. Each area placed a militarily organised citizen's resistance under the command of a civilian captain, which the only democratically elected department in the otherwise corporate composed imperial city.

Substantial changes to the cityscape only occurred after a large fire in 1719 when 430 houses burnt down in the north east Altstadt. In order to prevent such disasters in the future the council intensified construction specifications in 1720. Between 1740 and 1800 around 3,000 houses were either adapted or built anew. The number and width of overhangs were drastically limited. As well as that houses had to be built in future with the eaves side facing the road. Only small attics were certified as opposed to gabled dormers.

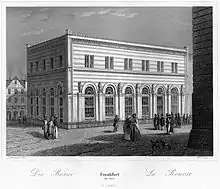

In 1785, Johann Georg Christian Hess took office as city architect. In 1809 he wrote a set of articles for the city of Frankfurt on behalf of the Grand Duke Carl Theodor von Dalberg, which basically remained in force until 1880. It made classicism mandatory as an architectural style. Hess was influenced by the spirit of the Enlightenment and campaigned radically for the architecture of classicism. He refused to preserve the numerous medieval buildings in Frankfurt because they did not meet his hygienic and aesthetic requirements. In the new town and in the new neighbourhoods emerging outside of the city walls, which were torn from 1804 to 1808, he effortlessly prevailed with his ideas, but in the old town he encountered stubborn resistance from conservative citizens. Only the new public buildings emerging in the old town, e.g. B. the Paulskirche (1833) or the Alte Börse (1843) on Paulsplatz corresponded to his classicist ideal.

The decline of the Altstadt in the 19th century

In the 19th century, Frankfurt was considered one of the most beautiful cities in Germany due to the numerous classical buildings. The medieval old town, on the other hand, was considered backward and outdated.

Goethe made Mephisto scoff at the old town:

- I chose a capital like this In the core citizen food horror. Crowds of alleyways, steep gables, Restricted market, cabbage, beets, onions; Meat banks where the Schmeissen live, To feast on the fat roasts; You will find it there at all times Certainly smell and activity. (Faust. The tragedy, part four, act four. High mountains)

The city historian Anton Kirchner also wrote in 1818 in his panel work Views of Frankfurt am Main about the buildings of the old town. The classicist zeitgeist is clear from the description:

The overload with carving and lappy artistry and the shapeless three- and four-story roofs make them easily recognizable by the eye. They do not belong to any order of architecture.

The loss of image corresponded to a political and economic decline. The Frankfurt fair, which was held twice a year in the old town, had passed to Leipzig in the middle of the 18th century. With the end of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, imperial coronations no longer took place.

The economic and political focus of Frankfurt has been the Neustadt since the Napoleonic Wars. After the restoration of the Free City of Frankfurt at the Vienna Congress, the Bundestag took its seat here in the Palais Thurn and Taxis.

Frankfurt became the European financial centre with the banking houses Bethmann, Rothschild and Gontard. The trade fair business no longer played a role in goods traffic; instead, the city's good transport links became the engine of the economic upswing. Around 1830 steam shipping was introduced on the Main, in 1836 Frankfurt joined the German Customs Union and as early as 1839 there was an important node in the emerging German rail network.

This economic boom passed the old town. At the latest after the annexation of Frankfurt by Prussia in 1866, the wealthy citizens moved to the new districts outside the ramparts, especially to the Westend. The city centre gradually shifted to the new town, where numerous Wilhelminian style buildings were erected at the Hauptwache, the Zeil and the Roßmarkt. The former exhibition halls in the buildings of the old town were transformed into warehouses or second-hand shops, the long-established craftsmen were forced to move to the new town with their customers. When the new small market hall between Fahrengasse and Hasengasse was built between 1877 and 1878, the traditional parapets also disappeared. The former Coronation Trail Markt no longer deserved its name, which was a symbol of the beginning social and structural deterioration of the old town. The horse-drawn tram, which started operating in 1872, did not reach the old town either.

The early photographs of the old town, for example by Carl Friedrich Mylius, or the watercolors by Carl Theodor Reiffenstein not only show the picturesque and beautiful sides of the old town, but are also witnesses of their decay.

The first street widenings were made in the second half of the 19th century in order to better open the old town to traffic. In 1855 the Liebfrauengasse between Liebfrauenberg and Zeil was built, in 1872 the Weißfrauengasse in the west to connect the old town with the train stations at the Taunusanlage. The associated loss of historical building substance, in particular the demolition of the white deer, was accepted.

The Lower Main Bridge and the Upper Main Bridge were built in 1874 and 1878. The Old Bridge and Fahrgasse lost their importance because the traffic flowed around the old town as far as possible.

The medieval houses, not to mention their backyards, were now often in poor condition. The hygienic conditions improved with the construction of an alluvial sewage system based on the English model from 1867. More and more houses were connected to the drinking water network, especially after the construction of a pipeline from Vogelsberg in 1873. In the course of industrialisation after 1870, numerous workers flocked to the city who quickly found cheap housing in the dilapidated buildings. Large parts of the old town were now considered to be the residential area of the proletariat and poorer petty bourgeois, where poverty, prostitution and crime were rampant.

At the same time, however, one began to discover the picturesque sides of the old town and open it up to tourism. On many half-timbered buildings, the plaster applied in the early 19th century was removed and the compartment was often painted historically afterwards. The painting preferred to refer to Frankfurt's important past, so that well-known postcard motifs were created in the touristically important places such as the Roseneck or the Five-Finger Square.

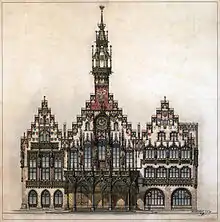

As in the classicist era, however, many measures were limited to public buildings: in 1874, the medieval city scales were demolished. Cathedral master builder Franz Josef Denzinger created a neo-Gothic, much larger new building until 1877. Other large medieval buildings such as churches or patrician houses were restored or decorated with historic jewelry. The best-known example is the conversion of the Roman by Max Meckel (1896–1900).

The old town in the early 20th century

By the beginning of the 20th century, the structure of the old town had remained largely unchanged since the Middle Ages, as a comparison with Merian copper engravings shows. In the old town alone there were around 2,000 historic buildings. The wooden half-timbered houses were still predominant, although there were a few stone patrician houses and numerous public buildings. Almost all stone buildings were made of local red sandstone.

The first really far-reaching structural change in the old town took place in the years 1904–1908 with the creation of a new road breakthrough; Braubachstrasse. This was in order to better open up the old town to traffic, especially for the tram. Around 100 old town houses, including art-historical complexes that date back to the Middle Ages, such as the Nürnberger Hof or the Hof Rebstock, were demolished. Representative new buildings were created, whichin their historizing architecture in turn (albeit on a larger and more magnificent scale) incorporated motifs from the old town. The corner house Braubachstrasse / Neue Kräme from 1906, for example, copies the typical Frankfurt town house around 1700.

Frankfurts old town was gradually recognised for its cultural and historical value as one of the best preserved old towns in Central Europe.

The resurgence and the "old town recovery"

The National Socialists planned to replace parts of the old town, until 1933 also a communist stronghold, with historicized new buildings. A citizens' initiative, the association of active friends of the old town founded in 1922 under the direction of art historian Fried Lübbecke, opposed these efforts. The federal government has had numerous old town buildings restored since 1926. However, as a pure association, it was limited in its resources, so that it was largely a matter of less substantial measures such as cleaning or repainting old buildings. Only with external financial help can comparatively important campaigns such as the purchase and renovation of the important Gothic patrician house Fürsteneck in Fahrgasse. Until the measures came to a complete standstill as a result of the war in the early 1940s, more than 600 buildings were thoroughly renovated, historically unsuitable extensions were removed and wells were repaired. Fried Lübbecke in particular described in detail how this made the old town into the good Stubb of Frankfurt within just a decade. Even facilities such as the unemployed kitchen, summer parties and Christmas presents for the old town children or the artist Christmas market made many old town residents feel proud of their homeland again.

After the National Socialist seizure of power in 1933, the new regime raised the so-called old town recovery to a prestige project.[3] In Nazi Germany, word creation was an umbrella term for measures taken by the city administration to preserve the old town as an overall monument; they took place simultaneously in Hamburg, Cologne, Braunschweig, Kassel and Hanover, among others. In Frankfurt am Main, a distinction was made between:

- Evictions,

- New buildings or reconstructive additions and

- Half-timbered exposures

The clearing out was a euphemism for in part extensive gutting measures, in modern usage the "renovation by demolition" that was common until the 1970s, which was carried out in some of the courtyards that were completely built up over the centuries. The Nazi city administration under Mayor Friedrich Krebs used the project to change the social structure of the old town in terms of its ideology. Old-established residents of the old town should be displaced in new housing developments on the outskirts of the city and the renovated old town apartments should primarily be awarded to traders, craftsmen and party members.[4] In doing so, the city also wanted to correspond to its Nazi honorary title awarded in 1935 as the city of German crafts. Fried Lübbecke and the poet Alfons Paquet opposed the destruction of medieval buildings. Her submissions were disqualified as "shouting from old town fanatics who judge things of community life not even out of bad will but from a limited view".[5][3]

As a result of the clearing out, behind the five-finger biscuit the handicraft farm between Goldhutgasse, Markt, Langer Schirn and Bendergasse as well as the cherry orchard between Großer and Kleiner Fischergasse and Mainkai south of the cathedral. The Hainer Hof to the north-east of the cathedral was also almost completely replaced by new buildings, some of which can still be seen today due to the minor war damage there. Likewise, the green space around the choir of the Carmelite Church is not a result of the war, but the goal of further evacuation, which eliminated numerous 19th-century extensions there.

Completely new buildings such as those in the Hainer Hof were rarely seen as part of the renovation. Mostly, it was a question of reconstructions or additions using traditional technology, which were necessary, in particular, after the cores had been removed to provide facades for the houses in the newly created courtyards. In the case of the half-timbered buildings in particular, however, entire rotten beam layers often had to be completely replaced. A good example of a reconstruction is the restoration of the Renaissance gable at the Haus Klein-Limpurg on the corner of Limpurger Gasse and Römerberg. It was based on illustrations of the building on old engravings, and during the construction work, substance from the Renaissance was actually uncovered, which had been reshaped during the classicist redesign of the building around 1800.

Finally, there were numerous half-timbered buildings in the entire old town area. Since many of them only took place in the late 1930s or early 1940s, they are hardly documented, let alone known, even in popular pictures of the old town. Among other things, exposures were made at the house Zur golden Weinrebe on the corner of Liebfrauenberg / Töngesgasse, at the house Zum Feigenbaum on the corner of Wildemannsgasse / Schnurgasse or at the Pesthaus at the five-finger cookie. The latter had been given a thematic repaint by the Altstadtbund just ten years earlier. Planned reconstructions of carefully stored half-timbered houses, such as the Great Warehouse or the Heydentanz House, on selected parcels of the old town no longer occurred.

The destruction in World War II

Template: main article At the latest since February 14, 1942, with the adoption of the British Area Bombing Directive, it became apparent that the old town of Frankfurt am Main could also become the target of the bomb war. The Federation of Friends of the Old Town, therefore, often with the help of external institutions such as the students from the Frankfurt School of Engineering or retired architects, had the entire existing building stock photographed and drawn as of summer 1942.

The first serious air raid on Frankfurt am Main hit the old town on October 4, 1943. The Romans and the Area between Liebfrauenberg, Töngesgasse and Hasengasse. Further attacks on December 20, 1943 and January 29, 1944 caused only minor damage in the old town, but destroyed the city archive with a large part of the archive material. On March 18, 1944, 846 British aircraft dropped their aerial bombs over Frankfurt. They mainly hit the eastern part of the old town and completely destroyed the area around Fahrgasse. They also caused severe damage in the western old town, the Paulskirche burned down completely.

The worst blow was yet to come: On March 22, 1944, another British air raid of 816 aircraft destroyed large parts of the old town that had previously been spared, including all churches except the Old Nikolaikirche and Leonhardskirche. According to official information, 500 air mines, 3,000 heavy explosive bombs and 1.2 million incendiary bombs were dropped on the city in just under an hour, with a clear focus on the city centre. As with previous air raids, this was part of the tactic: the majority of all houses in the old town were built in half-timbered construction, so that they largely burned completely in the unleashed firestorm. But patrician buildings from the Middle Ages built of stone, such as the canvas house or the stone house, were also destroyed by explosive devices. This air raid is also reproduced in a chalk drawing by the painter Karl Friedrich Lippmann, who painted what was happening on the Sachsenhausen side. The drawing shows how the old town and sky are brightly lit due to the fire.[6] The artist's house and emergency shelter were also bombed out.

Characteristic of the force of the attack is the fact that in the morning hours of March 24, 1944, there was not a single house in Tuchgaden, where practically all the ground floors consisted of massive stone vaults. Of the approximately 2,000 half-timbered houses, only one - the Wertheim am Fahrtor house - remained undamaged. The fire department had protected it with a water curtain to keep the escape route from Römerberg to the banks of the Main open.

The last major attack of the month followed on March 24, this time a daily attack by 262 aircraft of the American Air Force. In total, more than 1,500 people were killed in the attacks in March 1944. The main reason for the fact that the number of victims was not higher than in other cities was that, since the summer of 1940, the solidly built cellars of the old town houses had been interconnected. An emergency exit at the Fountain of Justice on the Römerberg alone saved around 800 people.

An impression of the destruction can be obtained from the historic model of the Treuner brothers exhibited in the Historical Museum, who in the years before the destruction had measured and reconstructed most of the houses in the old town on a scale of 1: 200. The debris model shown next shows the extent of the destruction of this bombing night. However, it should be viewed with caution, since contemporary photographs show significantly more surviving building remains.

The post-war period: reconstruction and second destruction

Large parts of the old town were completely rebuilt after the destruction of the Second World War, so that very few buildings with historical buildings remain are. After the clearing, modernisers and keepers faced each other - as is often the case at this time - so that there was initially a construction stop until 1952. Even the keepers, essentially represented by the Bund of old town friends, did not campaign for extensive reconstruction, but above all called for the preservation of the old road network with a small-scale new construction and the reconstruction of some important buildings.

Finally, albeit with a clear tendency towards modernisation, a mixed solution was found: some prominent monuments were reconstructed, the first being the Paulskirche in 1947 and the Goethe House in 1949. After 1952 followed the landmark of Frankfurt, the Roman, as well as the Staufen wall, the stone house, the Saalhof, the Carmelite monastery and the canvas house. From the destroyed endowment churches located in the old town, the cathedral, the Old Nikolaikirche, the Liebfrauenkirche and the Dominican monastery were rebuilt from urban funds from 1952 to 1962. The burnt-out ruins of the Gothic Weißfrauenkirche and the classicist German-Reformed church were removed in 1953.

Of the reconstructed buildings, only the Goethe House was largely restored to the original. Most other reconstructions were more or less simplified (for example the houses Silberberg, Frauenstein and Salzhaus in the Roman complex) or with modern additions (for example the stone house). Much of the former old town was built on in the simple style of the 1950s. The main result was multi-storey houses, partly as block perimeter development, partly as loosened row buildings, often with green inner courtyards. In addition, large-scale functional buildings such as the Federal Audit Office building in Frankfurt am Main, the Kleinmarkthalle and numerous parking garages were erected, including in 1956 the parking garage Hauptwache as Germany's first public parking garage.

Furthermore, new main roads were pulled through the wreckage, rejecting the historical floor plan. This should make car-friendly Frankfurt, which was often desired even before the war, a reality. This was realized in the form of the east–west axis, inaugurated on November 16, 1953 as the street at the Paulskirche and from 1955 until today known as Berliner Straße. It connects the also widened Weißfrauenstrasse with the north–south axis of Kurt-Schumacher-Strasse that runs through the inner city center. In 1955, the ten-story high-rise was completed at the intersection of Berliner Strasse and Fahrgasse. At 30 meters, it is the tallest residential building in the old town.

The area between the cathedral and the Römer initially remained a wasteland, the development of which was long debated. In the early 1970s, the Technical City Hall (1972–1974) and the Historical Museum (1971/72) were two large, monolithic buildings in a brutalist concrete style, regardless of historical layouts and shapes.

Reconstruction of historical buildings

In 1981 to 1983, the historic east side of the Römerberg was reconstructed with five half-timbered buildings, above all the famous town house Großer Engel. The other reconstructions, which are particularly fortunate to represent all forms of the local half-timbered building from Gothic to Classicism, can be seen as prototypical for the urban effect of the development of the entire district that was preserved until 1944.

Unlike the historical models, the facades of the new buildings with their half-timbering remained unplastered. Some of its structure is extrapolated from known individual constructive forms, photographs and analogue conclusions, since building plans have not been preserved for all buildings. Since the beams and their infill were traditionally plastered or slated, decorative forms were installed in the now visible half-timbering, which were borrowed from other buildings of comparable construction.

After just a few years, there was considerable structural damage that required extensive renovation. As it turned out, the contracted construction companies no longer had the essential skills for a half-timbered building. For example, the timber from Alsace was not dried long enough and the beams were not properly connected.

The Kunsthalle Schirn and the postmodern new buildings on Saalgasse were created simultaneously with the historicizing reconstructions. In 1991 the Museum of Modern Art opened on Braubachstrasse. The Haus am Dom, an educational center of the Catholic diocese of Limburg, was built in 2007 on Domstrasse on the preserved substructure of the former main customs office from 1927.

After the decision of the city council to demolish the Technical City Hall,[7] A technical and emotional discussion about the reconstruction of this old town district began when almost the entire historical nucleus of the city between the cathedral and the Roman became an open space again. In 2007, the factions of the CDU and Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen, ruling since the municipal elections in Frankfurt in 2006, reached an agreement with the FDP and the free voters against the votes of the SPD and Die Linke for the new construction of the Dom-Römer area[8] on a compromise.

The city had eight historical buildings reconstructed as the client, with "the historical district floor plan largely being used as the basis for planning", including the Haus zur Goldenen Waage and the Neue Rote Haus am Markt, the Haus zum Esslinger (also as the aunt's house) Marked Melber) at the Hühnermarkt and the Goldene Lämmchen. In addition, the city had the Alter Esslinger house, the Klein Nürnberg house and parts of the Rebstock farm, located between the latter two. The remaining 32 parcels were awarded to builders who had 7 further reconstructions built. For the new buildings, with which well-known architects were commissioned to plan, there was a strict design statute that stipulated, among other things, the shape of the roof, the height of the buildings and the materials used.

Construction started in 2012. At the end of 2017, the buildings were completed externally. In September 2018, the New Old Town was opened with a three-day festival

The concrete building of the Historical Museum was demolished in 2012 and replaced by a new building opened in October 2017.

Districts and sights of the Altstadt

There are numerous sights in the old town - although most of the buildings are only reconstructions after severe war destruction. All sights are close together and can be reached by tram and subway.

Römerberg and surroundings

The Römerberg is the centre of the old town. Here stands the Römer, the historic town hall and symbol of the city. It was acquired in 1405 by the city, which needed a new town hall, as the previous town hall had to be demolished to build the cathedral tower. By 1878 the ten neighboring houses were also acquired by the city and structurally connected to the Roman. The five houses next to each other, whose facade faces the Römerberg, are called Alt Limpurg, Zum Römer, Löwenstein, Frauenstein and Salzhaus. Before its destruction, the salt house was one of the most beautiful half-timbered houses in Germany. It was rebuilt in a simplified manner after the war was destroyed.

In the middle of the square is the Justice Fountain, which was built from sandstone in the 17th century. The construction was replaced in 1887 by a bronze replica. His name comes from the statue of Justitia that crowns him. In contrast to her depictions, Justitia was not blindfolded in Frankfurt. According to tradition, the fountain was fed with red and white wine at imperial coronations.

Since the Middle Ages, the square has been surrounded by residential and commercial buildings - the reconstructed half-timbered houses of the Samstagsberg (also known as the Ostzeile ), including the houses Großer and Kleiner Engel and Schwarzer Stern, are particularly worth mentioning here.

The Wertheim House (around 1600), is the only completely undamaged preserved half-timbered house in the old town. It is an ornate three-story Renaissance house with the stone ground floor common in Frankfurt. Opposite is the Rententurm, an important Frankfurt port building, where customs duties and port fees were collected. It was completed in 1456.

North of the Römerberg on Paulsplatz is the New Town Hall, built around 1900 with rich Neo-Renaissance and Neo-Baroque decor, as well as the Paulskirche, where the German National Assembly met in 1848/1849.

Cathedral area

Around 300 meters east of the Römerberg rises the largest and most important church in the city, the Catholic imperial cathedral St. Bartholomew with its 95 meter high west tower. The majority of German kings were chosen here since the Middle Ages. From 1562 to 1792, 10 emperors of the Holy Roman Empire were crowned in the Bartholomäuskirche. The market (Kramgasse in the Middle Ages) runs between the cathedral and Römerberg, the main street of the old town that was rebuilt more than 70 years after its destruction. The Coronation Trail ran here, which the Emperor took after the coronation to celebrate the Römerberg.

In front of the west tower of the cathedral is the archaeological garden, which was built over 2012 to 2015 with the town house on the market, in which the remains of the foundations of the Roman military camp, the Carolingian Palatinate and medieval town houses are open to the public. The streets behind the Lämmchen, Neugasse and the Hühnermarkt, which have been resurrected after the demolition of the Technical Town Hall, with their new buildings and reconstructions have been accessible again since May 2018. With the House of the Golden Waage and the New Red House, two of the most famous half-timbered buildings in the old town were rebuilt. Further reconstructions are the houses Grüne Linde, Würzgarten and Rotes Haus am Markt. Striking new buildings are the Großer Rebstock houses on the market next to the Haus am Dom, Neues Paradies on the corner of the Hühnermarkt, Altes Kaufhaus, the city of Milan and Zu den Drei Römer on the western edge of the new development area.

On the north side of the Old Market is the Stone House, a 15th-century Gothic patrician building. It is the seat of the Frankfurter Kunstverein. A gate passage from the Nürnberger Hof (around 1410), the trade fair quarter of the Nuremberg merchants, has been preserved near the Stone House.

The Kunsthalle Schirn, opened in 1986, stretches south of the market, for example along the former Bendergasse. In the same block, on the north side of Saalgasse, townhouses were built in the proportions of the former old town, but in the postmodern architectural style of the time. South of the cathedral on Weckmarkt is the canvas house, architecturally related to the stone house, which today houses the Museum of Comic Art.

Between the cathedral, Fahrgasse and Main was built in the style of the time in the 1950s. Most of the historic streets of the former butcher's quarter were lost. Quiet, green courtyards were created, whose irregular design and small passageways could remind people with a lot of imagination of the enchanted old town streets. In the former old town there were numerous small fountains, many of which could be saved and put back in the courtyards.

Western old town

The most striking building in the western old town is the Leonhardskirche, the only church in downtown Frankfurt that remained undamaged in the Second World War. The north portal and the two east towers are still Romanesque, the basilica itself is late Gothic. Cathedral choir Madern Gerthener designed the high choir.

A few steps away is the former Carmelite monastery, today the seat of the Institute for Urban History and the Archaeological Museum.[9]

The Goethe House, the poet's birthplace, is located north of Berliner Strasse in the Großer Hirschgraben.

Northern old town

The northern old town is the area between today's Berliner Straße and the Staufenmauer, the former course of which can be seen on the Graben streets (Hirschgraben, Holzgraben). It is the area that the city gained through the second expansion in the 12th century. In contrast to the older part in the area of the former Carolingian Palatinate, which has an irregular road network, the northern old town had an almost right-angled road structure.

Most of the northern part of the old town was destroyed on June 26, 1719 during the "Great Christian Fire" (eight years earlier to distinguish it from the "Great Jewish Fire" in Judengasse). In the area between Fahrgasse, Schnurgasse and Töngesgasse, 282 people died and 425 houses were destroyed.[10] However, the area was quickly rebuilt on the old, small plots.

Eastern old town

The main street of the eastern old town was the Fahrgasse. It ran from the Bornheim gate at the Konstablerwache to the Old Bridge; all traffic over the only Main crossing between Mainz and Aschaffenburg passed through this street.

To the east of Fahrgasse is the former Dominican monastery, rebuilt from 1953 to 1957 on the old floor plan, with the Church of the Holy Spirit. It is the seat of the Evangelical City Deanery and the Evangelical Regional Association Frankfurt. To the east of it is Börneplatz, the largest and busiest square in the district. Under changing names, it was the centre of Jewish life in Frankfurt. The Judengasse ended here, since 1882 the Börneplatz synagogue, destroyed in the November pogroms in 1938, was here, and the Old Jewish Cemetery, Battonnstrasse, whose oldest grave monuments date from 1272, is still located here today. In the Judengasse Museum, part of the Frankfurt Jewish Museum, excavated remains of the ghetto and the synagogue can be viewed.

Former and reconstructed buildings

Many architectural monuments as well as striking buildings or street corners or entire streets of the old town were lost as a result of the Second World War or due to demolition, some of them were rebuilt or reconstructed - some more than 70 years after their destruction. Here are a few of the most important:

- The old stock exchange on Paulsplatz was a building of late classicism, built in 1843, burned out in 1944 and demolished in 1952.

- The old bridge was first mentioned in 1222. It has been destroyed and rebuilt at least 18 times over the centuries. In 1914 the only beautiful monument from earlier times (Goethe) worthy of such a large city was demolished. The New Old Bridge, inaugurated in its place in 1926, was simply rebuilt after the war was destroyed in 1965.

- Bendergasse was the epitome of an old town alley with numerous five- to six-story half-timbered buildings from the 16th to 18th centuries. Destroyed in 1944, the site was cleared until 1950. Today the Schirn art gallery is located here.

- The Five-Finger Square was a popular postcard motif, a tiny old town square near the Römerberg (burned out in 1944).

- The Haus zum Esslinger on the Chicken Market was a baroque altered, late Gothic half-timbered building in which Goethe's aunt Johanna Melber lived in the 18th century, which he also described in his autobiographical work Poetry and Truth. The building burned down in 1944 and the ruins were removed in 1950. The reconstruction opened in 2018 is the seat of the Struwwelpeter Museum.

- The Fürsteneck house was a Gothic patrician stone building from the 13th century. Extensively restored in the 1920s, it burned out in 1944. The remains were torn down after the war.

- The House of the Golden Scales in Höllgasse west of the cathedral was an elaborately decorated Renaissance half-timbered building. Built between 1618 and 1619, it was renovated at the beginning of the 20th century. The Golden Scales burned out in 1944 and its remains were cleared in 1950. The reconstruction of the Golden Scales will reopen in 2018 as a branch of the Historical Museum.

- The Lichtenstein house was a Gothic patrician stone house on the south-western Römerberg, which was changed in the 18th century in the Baroque style. It burned down in 1944, the well-preserved but unsecured ruin was badly damaged in a storm in 1946 and, shortly thereafter, was torn down despite the planned reconstruction.

- The Rebstock farm was a half-timbered building from the 17th century and one of the most important inns in the old town. The poet Friedrich Stoltze was born here in 1816. Large parts were demolished at the beginning of the 20th century for the breakthrough of Braubachstrasse, the rest were destroyed in 1944.

- Behind the Lämmchen was the name of a narrow alley between the Nürnberger Hof and the Chicken Market, in which some of the most important half-timbered houses in the city were located, including the houses Zum Nürnberger Hof, Zum Mohrenkopf and Goldenes Lämmchen. From 1974 to 2010, the entire area with the Technical Town Hall was built over.

- The Chicken Market between the cathedral and the Römer was a picturesque ensemble of half-timbered houses from the 17th and 18th centuries: the most important were the Old Red House and the New Red House at the entrance to the Tuchgaden. Both have since been reconstructed. The Stoltze Fountain stood on the chicken market until 1944, which returned to its regular place in 2016. The Schildknecht house on Hühnermarkt, built around 1405, had the largest overhang of all Frankfurt half-timbered houses at almost two meters.

- From 1462 to 1796, Judengasse was the Frankfurt ghetto. Their remains were burned down and rebuilt several times between 1874 and 1888. Only the synagogue and the Rothschildhaus were initially preserved. The synagogue fell victim to the November pogroms in 1938, the Rothschildhaus in 1944 to the bombing.

- The herb market was a place at the exit of Bendergasse to the cathedral. The baroque stone houses of the late 18th century were completely destroyed in 1944.

- The market was historically the most important old town alley in Frankfurt. The coronation route of the German emperors from the cathedral to the Roman ran through him. The countless, mostly richly decorated half-timbered buildings from the 16th to the 18th centuries were destroyed in 1944. At the beginning of the 1970s, the area was built over with the Technical Town Hall and the Römer underground station. After the town hall was demolished, the market was built again. The houses Goldene Waage, Grüne Linde, Rotes Haus, Neues Rotes Haus, Schlegel and Würzgarten were reconstructed.

- The flour scale at Garküchenplatz was built in 1719. The flour was officially weighed and cleared on the ground floor, and the upper floors served as a city prison until 1866. The building was extensively renovated in 1938 and destroyed in 1944.

- The Nürnberger Hof was an extensive building complex from the 13th century. It was largely torn down when the Braubachstrasse was built in 1905. The rest suffered severe bomb damage in 1944 and was demolished in 1953 except for the baroque gate in favor of Berliner Strasse.

- The Roseneck was a very beautiful group of half-timbered houses south of the cathedral. It was completely destroyed in 1944.

- Saalgasse ran south of the Old Nikolaikirche parallel to Bendergasse. Its numerous multi-storey half-timbered buildings and some stone buildings from the 16th to the 18th centuries were destroyed in 1944 and the remains were cleared after the war. The south side was rebuilt in the 1950s, and a number of postmodern town houses were built on the north side in the early 1980s.

- The Scharnhäuser on Heilig-Geist-Plätzchen in Saalgasse were two baroque modified, late Gothic half-timbered buildings with public passageways on their ground floors on wooden pillars. In the 1770s, Johann Wolfgang Goethe conducted a successful lawsuit around one of the buildings. The buildings burned down in 1944 and were cleared until 1950.

- The Weckmarkt, south of the cathedral, was home to the canvas house built in 1399 and the former city scales from 1504, two of the most important medieval stone buildings in Frankfurt. The city scales were rebuilt around 1880 by cathedral architect Franz Josef Denzinger in the neo-Gothic style. It housed the city archive until it was destroyed in 1944. The ruins of the canvas house were rebuilt in 1982.

Culture

In the old town there are numerous museums that are part of the so-called museum bank along the Main, including the Jewish Museum, the Archaeological Museum in the Carmelite Monastery, the Historical Museum with a focus on city history, the Schirn Art Gallery and the Museum of Modern Art. The Steinerne Haus, seat of the Frankfurter Kunstverein, the canvas house and the Literature house Frankfurt in the old city library are important domiciles of the Frankfurt art scene, which are located in three reconstructed historical buildings.

Among the Frankfurt theatres, three, namely the comedy, the Volksbühne and the cabaret Die Schmiere, have their venues in the old town. In the past, the old town was generally not particularly busy in the evening, except for major events such as the Museumsuferfest. Public traffic has increased significantly since the beginning of the 21st century, especially among tourists. During the 2006 World Cup, numerous soccer games were broadcast in the specially built Main Arena, an open-air cinema for around 15,000 visitors on the northern bank of the Main.

Literature

- Johann Georg Battonn: Local description of the city of Frankfurt am Main - Volumes I – VI. Association for history and antiquity to Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 1861-1871

- Hartwig Beseler, Niels Gutschow: Fate of war in German architecture. Losses - damage - reconstruction. Documentation for the territory of the Federal Republic of Germany. Volume II: South. Panorama Verlag, Wiesbaden 2000, ISBN 3-926642-22-X.

- Friedrich Bothe: History of the city of Frankfurt am Main. Publishing house of Moritz Diesterweg, Frankfurt am Main 1913.

- Wilhelm Carlé (Bearb.): The new old town. 1926 yearbook of the federal government to old town friends Frankfurt a. Main. Holbein-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1926.

- Olaf Cunitz: Urban redevelopment in Frankfurt am Main 1933–1945. Final thesis to obtain the Magister Artium, Johann Wolfgang Goethe University Frankfurt am Main, Faculty 08 History / Historical Seminar, 1996 (online; PDF; 11,2 MB).

- Georg Hartmann, Fried Lübbecke: Old Frankfurt. A legacy. Verlag Sauer and Auvermann KG, Glashütten / Taunus 1971.

- Julius Hülsen, Rudolf Jung, Carl Wolff: The monuments in Frankfurt am Main. Self-publishing / Völcker, Frankfurt am Main 1896–1914.

- Georg Ludwig Kriegk: History of Frankfurt am Main in selected representations. Heyder and Zimmer, Frankfurt am Main 1871.

- Fried Lübbecke: The face of the city. Based on Frankfurt plans by Faber, Merian and Delkeskamp 1552–1864. Waldemar Kramer publishing house, Frankfurt am Main 1952.

- Walter Sage: The community center in Frankfurt a. M. until the end of the Thirty Years' War. Wasmuth, Tübingen 1959 (Das Deutsche Bürgerhaus 2).

- Philipp Sturm, Peter Cachola Schmal, ed. (2018), Die immer Neue Altstadt: Bauen zwischen Dom und Römer seit 1900 (in German), Berlin: Jovis Verlag, ISBN 978-3-86859-501-7. Katalog zur Ausstellung im Deutschen Architekturmuseum.

- Heinrich Völcker: The city of Goethe. Frankfurt am Main in the XVIII. Century. Blazek & Bergmann University Bookstore, Frankfurt am Main 1932.

- Magnus Wintergerst: Franconofurd. Volume I. The Findings of the Carolingian-Ottonian Palatinate from the Frankfurt Old Town Excavations 1953–1993. Archaeological Museum Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 3-88270-501-9 (Writings of the Archaeological Museum Frankfurt 22/1).

- Hermann Karl Zimmermann: The artwork of a city. Frankfurt am Main as an example. Verlag Waldemar Kramer, Frankfurt am Main 1963.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Frankfurt-Altstadt. |

- Virtual Altstadt (Animated model of Frankfurt's old town 1944)

- Frankfurt am Main in the bombing war

- Freunde Frankfurts – Successor association of the "Association of Friends of the Old Town"

- Reconstruction of the Frankfurt Old Town (Altstadtforum von Jürgen E. Aha)

- Documentation Altstadt: Planning area Dom-Römer, City planning office of the city Frankfurt am Main – October 2006 (PDF)

- New discovered color slides provide insight into what has not yet been destroyed Frankfurt, hr-fernsehen.de, 20. February 2018

References

- Gerner, Manfred (1979). Half-timbering in Frankfurt am Main. Frankfurter Sparkasse from 1822. Frankfurt am Main 1979: Verlag Waldemar Kramer, Frankfurt am Main. ISBN 3-7829-0217-3.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "domroemer website". 24 June 2020.

- Heike Drummer; Jutta Zwilling (2015-11-03). "Altstadtgesundung". Frankfurt 1933–1945. Institut für Stadtgeschichte. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- Theo Derlam (1983), Wolfgang Klötzer (ed.), "Die Frankfurter Altstadtgesundung", Die Frankfurter Altstadt. Eine Erinnerung (in German), Frankfurt am Main, pp. 315–323

- Gerner, Manfred (1979). Half-timbering in Frankfurt am Main . Frankfurter Sparkasse from 1822. Frankfurt am Main: Verlag Waldemar Kramer, Frankfurt am Main. ISBN 3-7829-0217-3.

- Abbildung der Zeichnung auf der Website frankfurt1933-1945.de ().

- "Vortrag des Magistrats an die Stadtverordnetenversammlung M 112 2007 vom 20. Juni 2007". PARLIS – Parlamentsinformationssystem der Stadtverordnetenversammlung Frankfurt am Main. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

- "Wortprotokoll über die 15. Plenarsitzung der Stadtverordnetenversammlung am Donnerstag, dem 6. September 2007 (16.02 Uhr bis 22.30 Uhr)". PARLIS – Parlamentsinformationssystem der Stadtverordnetenversammlung Frankfurt am Main. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

- Schomann, Heinz (1977), 111 Frankfurter Baudenkmäler schildern. (in German), Frankfurt am Main: Dieter Fricke, p. 28, ISBN 3-88184-008-7

- Chronik der Frankfurter Feuerwehr

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Frankfurt am Main/Altstadt und Innenstadt. |