Bonn

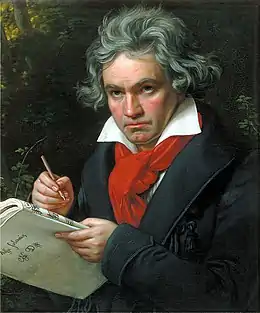

The Federal city of Bonn (German pronunciation: [bɔn] (![]() listen) Latin: Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About 24 km (15 mi) south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ruhr region, Germany's largest metropolitan area, with over 11 million inhabitants. It is famously known as the birthplace of Ludwig van Beethoven in 1770 as well as the capital city of West Germany until 1990.

listen) Latin: Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About 24 km (15 mi) south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ruhr region, Germany's largest metropolitan area, with over 11 million inhabitants. It is famously known as the birthplace of Ludwig van Beethoven in 1770 as well as the capital city of West Germany until 1990.

Bonn | |

|---|---|

A view over the Bundesviertel (English: "Federal Quarter": the location of the German federal government presence in Bonn) | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Bonn within North Rhine-Westphalia  | |

Bonn  Bonn | |

| Coordinates: 50°44′N 7°6′E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | North Rhine-Westphalia |

| Admin. region | Cologne |

| District | Urban district |

| Founded | 1st century BC |

| Government | |

| • Lord Mayor | Katja Dörner (Greens) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 141.06 km2 (54.46 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 60 m (200 ft) |

| Population (2019-12-31)[1] | |

| • Total | 329,673 |

| • Density | 2,300/km2 (6,100/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal codes | 53111–53229 |

| Dialling codes | 0228 |

| Vehicle registration | BN |

| Website | www.bonn.de |

Founded in the 1st century BC as the Roman settlement Germania Inferior, Bonn is one of Germany's oldest cities. From 1597 to 1794, Bonn was the capital of the Electorate of Cologne, and residence of the Archbishops and Prince-electors of Cologne. From 1949 to 1990, Bonn was the capital of West Germany, and Germany's present constitution, the Basic Law, was declared in the city in 1949. The era when Bonn served as the capital of West Germany is referred to by historians as the Bonn Republic.[2] From 1990 to 1999, Bonn served as the seat of government – but no longer capital – of reunited Germany.

Due to a political compromise (Berlin-Bonn Act) following the reunification, the German federal government maintains a substantial presence in Bonn. Roughly a third of all ministerial jobs are located in Bonn as of 2019,[3] and the city is considered a second, unofficial, capital of the country.[4] Bonn is the secondary seat of the President, the Chancellor, the Bundesrat and the primary seat of six federal government ministries and twenty federal authorities. The title of Federal City (German: Bundesstadt) reflects its important political status within Germany.[5]

The headquarters of Deutsche Post DHL and Deutsche Telekom, both DAX-listed corporations, are in Bonn. The city is home to the University of Bonn and a total of 20 United Nations institutions, the highest number in all of Germany.[6] These institutions include the headquarters for Secretariat of the UN Framework Convention Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Secretariat of the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), and the UN Volunteers programme.[7]

Geography

Topography

Situated in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ruhr region, Germany's largest metropolitan area with over 11 million inhabitants, Bonn lies within the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, on the border with Rhineland-Palatinate. Spanning an area of more 141.2 km2 (55 sq mi) on both sides of the river Rhine, almost three-quarters of the city lies on the river's left bank.

To the south and to the west, Bonn is bordering the Eifel region which encompasses the Rhineland Nature Park. To the north, Bonn borders the Cologne Lowland. Natural borders are constituted by the river Sieg to the north-east and by the Siebengebirge (also known as the Seven Hills) to the east. The largest extension of the city in north–south dimensions is 15 km (9 mi) and 12.5 km (8 mi) in west–east dimensions. The city borders have a total length of 61 km (38 mi). The geographical centre of Bonn is the Bundeskanzlerplatz (Chancellor Square) in Bonn-Gronau.

Administration

The German state of North Rhine-Westphalia is divided into five governmental districts (German: Regierungsbezirk), and Bonn is part of the governmental district of Cologne (German: Regierungsbezirk Köln). Within this governmental district, the city of Bonn is an urban district in its own right. The urban district of Bonn is then again divided into four administrative municipal districts (German: Stadtbezirk). These are Bonn, Bonn-Bad Godesberg, Bonn-Beuel and Bonn-Hardtberg. In 1969, the independent towns of Bad Godesberg and Beuel as well as several villages were incorporated into Bonn, resulting in a city more than twice as large as before.

| Municipal district (Stadtbezirk) | Coat of arms | Population (as of December 2014)[8] | Sub-district (Stadtteil) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bad Godesberg | 73.172 | Alt-Godesberg, Friesdorf, Godesberg-Nord, Godesberg-Villenviertel, Heiderhof, Hochkreuz, Lannesdorf, Mehlem, Muffendorf, Pennenfeld, Plittersdorf, Rüngsdorf, Schweinheim | |

| Beuel | 66.695 | Beuel-Mitte, Beuel-Ost, Geislar, Hoholz, Holtorf, Holzlar, Küdinghoven, Limperich, Oberkassel, Pützchen/Bechlinghoven, Ramersdorf, Schwarzrheindorf/Vilich-Rheindorf, Vilich, Vilich-Müldorf | |

| Bonn | 149.733 | Auerberg, Bonn-Castell (known until 2003 as Bonn-Nord), Bonn-Zentrum, Buschdorf, Dottendorf, Dransdorf, Endenich, Graurheindorf, Gronau, Ippendorf, Kessenich, Lessenich/Meßdorf, Nordstadt, Poppelsdorf, Röttgen, Südstadt, Tannenbusch, Ückesdorf, Venusberg, Weststadt | |

| Hardtberg | 33.360 | Brüser Berg, Duisdorf, Hardthöhe, Lengsdorf |

Climate

Bonn has an oceanic climate (Cfb).[9] In the south of the Cologne lowland in the Rhine valley, Bonn is in one of Germany's warmest regions.

| Climate data for Bonn | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 4.7 (40.5) |

6.1 (43.0) |

9.9 (49.8) |

14.1 (57.4) |

18.6 (65.5) |

21.8 (71.2) |

23.2 (73.8) |

22.8 (73.0) |

19.8 (67.6) |

14.7 (58.5) |

9 (48) |

5.8 (42.4) |

14.2 (57.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.4 (36.3) |

2.8 (37.0) |

6.3 (43.3) |

9.7 (49.5) |

14.0 (57.2) |

16.7 (62.1) |

18.8 (65.8) |

18.3 (64.9) |

14.6 (58.3) |

10.5 (50.9) |

6.2 (43.2) |

3.1 (37.6) |

10.3 (50.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.6 (30.9) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

1.6 (34.9) |

4.5 (40.1) |

8.1 (46.6) |

11.3 (52.3) |

13 (55) |

12.5 (54.5) |

10 (50) |

6.4 (43.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

0.6 (33.1) |

5.9 (42.5) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 61.0 (2.40) |

54.0 (2.13) |

64.0 (2.52) |

54.0 (2.13) |

72.0 (2.83) |

86.0 (3.39) |

78.0 (3.07) |

78.0 (3.07) |

72.0 (2.83) |

63.0 (2.48) |

66.0 (2.60) |

68.0 (2.68) |

816.0 (32.13) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 51.0 | 76.0 | 110.0 | 163.0 | 190.0 | 195.0 | 209.0 | 194.0 | 141.0 | 104.0 | 55.0 | 41.0 | 1,529 |

| Source 1: Deutscher Wetterdienst (Bonn-Rohleber, period 1971– 2010) | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Climate-Data.org, high and low averages (altitude: 64m)[9] | |||||||||||||

History

Founding and Roman times

The history of the city dates back to Roman times. In about 12 BC, the Roman army appears to have stationed a small unit in what is presently the historical centre of the city. Even earlier, the army had resettled members of a Germanic tribal group allied with Rome, the Ubii, in Bonn. The Latin name for that settlement, "Bonna", may stem from the original population of this and many other settlements in the area, the Eburoni. The Eburoni were members of a large tribal coalition effectively wiped out during the final phase of Caesar's War in Gaul. After several decades, the army gave up the small camp linked to the Ubii-settlement. During the 1st century AD, the army then chose a site to the north of the emerging town in what is now the section of Bonn-Castell to build a large military installation dubbed Castra Bonnensis, i.e., literally, "Fort Bonn". Initially built from wood, the fort was eventually rebuilt in stone. With additions, changes and new construction, the fort remained in use by the army into the waning days of the Western Roman Empire, possibly the mid-5th century. The structures themselves remained standing well into the Middle Ages, when they were called the Bonnburg. They were used by Frankish kings until they fell into disuse. Eventually, much of the building materials seem to have been re-used in the construction of Bonn's 13th-century city wall. The Sterntor (star gate) in the city center is a reconstruction using the last remnants of the medieval city wall.

To date, Bonn's Roman fort remains the largest fort of its type known from the ancient world, i.e. a fort built to accommodate a full-strength Imperial Legion and its auxiliaries. The fort covered an area of approximately 250,000 square metres (62 acres). Between its walls it contained a dense grid of streets and a multitude of buildings, ranging from spacious headquarters and large officers' quarters to barracks, stables and a military jail. Among the legions stationed in Bonn, the "1st", i.e. the Prima Legio Minervia, seems to have served here the longest. Units of the Bonn legion were deployed to theatres of war ranging from modern-day Algeria to what is now the Russian republic of Chechnya.

The chief Roman road linking the provincial capitals of Cologne and Mainz cut right through the fort where it joined the fort's main road (now, Römerstraße). Once past the South Gate, the Cologne–Mainz road continued along what are now streets named Belderberg, Adenauerallee et al. On both sides of the road, the local settlement, Bonna, grew into a sizeable Roman town. Bonn is shown on the 4th century Peutinger Map.

In late antiquity, much of the town seems to have been destroyed by marauding invaders. The remaining civilian population then took refuge inside the fort along with the remnants of the troops stationed here. During the final decades of Imperial rule, the troops were supplied by Franci chieftains employed by the Roman administration. When the end came, these troops simply shifted their allegiances to the new barbarian rulers, the Kingdom of the Franks. From the fort, the Bonnburg, as well as from a new medieval settlement to the South centered around what later became the minster, grew the medieval city of Bonn. Local legends arose from this period that the name of the village came from Saint Boniface via Vulgar Latin *Bonnifatia, but this proved to be a myth.

Middle Ages and Early Modern times

Between the 11th and 13th centuries, the Romanesque style Bonn Minster was built, and in 1597 Bonn became the seat of the Archdiocese of Cologne. The city gained more influence and grew considerably. The city was subject to a major bombardment during the Siege of Bonn in 1689. The elector Clemens August (ruled 1723–1761) ordered the construction of a series of Baroque buildings which still give the city its character. Another memorable ruler was Max Franz (ruled 1784–1794), who founded the university and the spa quarter of Bad Godesberg. In addition he was a patron of the young Ludwig van Beethoven, who was born in Bonn in 1770; the elector financed the composer's first journey to Vienna.

In 1794, the city was seized by French troops, becoming a part of the First French Empire. In 1815 following the Napoleonic Wars, Bonn became part of the Kingdom of Prussia. Administered within the Prussian Rhine Province, the city became part of the German Empire in 1871 during the Prussian-led unification of Germany. Bonn was of little relevance in these years.

20th century and the "Bonn Republic"

During the Second World War, Bonn acquired military significance because of its strategic location on the Rhine, which formed a natural barrier to easy penetration into the German heartland from the west. The Allied ground advance into Germany reached Bonn on 7 March 1945, and the US 1st Infantry Division captured the city during the battle of 8–9 March 1945.[10]

After the Second World War, Bonn was in the British zone of occupation. Following the advocacy of West Germany's first chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, a former Cologne Mayor and a native of that area, Bonn became the de facto capital, officially designated the "temporary seat of the Federal institutions," of the newly formed Federal Republic of Germany in 1949. However, the Bundestag, seated in Bonn's Bundeshaus, affirmed Berlin's status as the German capital. Bonn was chosen as the provisional capital and seat of government despite the fact that Frankfurt already had most of the required facilities and using Bonn was estimated to be 95 million DM more expensive than using Frankfurt. Bonn was chosen because Adenauer and other prominent politicians intended to make Berlin the capital of the reunified Germany, and felt that locating the capital in a major city like Frankfurt or Hamburg would imply a permanent capital and weaken support in West Germany for reunification.

In 1949, the Parliamentary Council in Bonn drafted and adopted the current German constitution, the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany. As the political centre of West Germany, Bonn saw six Chancellors and six Presidents of the Federal Republic of Germany. Bonn's time as the capital of West Germany is commonly referred to as the Bonn Republic, in contrast to the Berlin Republic which followed reunification in 1990.[11]

Bonn in the "Berlin Republic"

German reunification in 1990 made Berlin the nominal capital of Germany again. This decision, however, did not mandate that the republic's political institutions would also move. While some argued for the seat of government to move to Berlin, others advocated leaving it in Bonn – a situation roughly analogous to that of the Netherlands, where Amsterdam is the capital but The Hague is the seat of government. Berlin's previous history as united Germany's capital was strongly connected with the German Empire, the Weimar Republic and more ominously with Nazi Germany. It was felt that a new peacefully united Germany should not be governed from a city connected to such overtones of war. Additionally, Bonn was closer to Brussels, headquarters of the European Economic Community. Former chancellor and mayor of West Berlin Willy Brandt caused considerable offence to the Western Allies during the debate by stating that France would not have kept the seat of government at Vichy after Liberation.[12]

The heated debate that resulted was settled by the Bundestag (Germany's parliament) only on 20 June 1991. By a vote of 338–320,[13] the Bundestag voted to move the seat of government to Berlin. The vote broke largely along regional lines, with legislators from the south and west favouring Bonn and legislators from the north and east voting for Berlin.[14][15] It also broke along generational lines as well; older legislators with memories of Berlin's past glory favoured Berlin, while younger legislators favoured Bonn. Ultimately, the votes of the eastern German legislators tipped the balance in favour of Berlin.[16]

From 1990 to 1999, Bonn served as the seat of government of reunited Germany. In recognition of its former status as German capital, it holds the name of Federal City (German: Bundesstadt). Bonn currently shares the status of Germany's seat of government with Berlin, with the President, the Chancellor and many government ministries (such as Food & Agriculture and Defence) maintaining large presences in Bonn. Over 8,000 of the 18,000 federal officials remain in Bonn.[4] A total of 19 United Nations (UN) institutions operate from Bonn today.

Politics

City council

The city council of Bonn used to be based in the Rococo-style and 1737 built Altes Rathaus (old city hall) adjacent to Bonn's central market square. However, due to the enlargement of Bonn in 1969 through the incorporation of Beuel and Bad Godesberg, it moved into the larger Stadthaus facilities further up north. This was necessary for the city council to accommodate the increased number of representatives. The mayor of Bonn still sits in the Altes Rathaus, which is also used for representative and official purposes.

As of the 2020–2025 election cycle, the Christian Democrats (CDU) and the Greens (Bündnis'90/Die Grünen) hold 17 seats respectively, followed by the Social Democrats (SPD) with 11 seats, the local Bürgerbund Bonn with 5 seats, the Liberals (FDP) and Volt with 3 seats respectively, the Left (Die Linke) with 4 seats, , the Alternative for Germany (AfD) with 2 seats, and independent candidates with a total of 4 seats. There are currently 66 seats in the city council of Bonn.[17]

The mayor is Katja Dörner (Bündnis '90/Die Grünen), elected in 2020.[18]

Landtag election

Four delegates represent the Federal city of Bonn in the Landtag of North Rhine-Westphalia. The last election took place in May 2017. The current delegates are Guido Déus (CDU), Christos Katzidis (CDU), Joachim Stamp (FDP) and Franziska Müller-Rech (FDP).

German federal election

Bonn's constituency is called Bundeswahlkreis Bonn (096). In the German federal election 2017, Ulrich Kelber (SPD) was elected a member of German Federal parliament, the Bundestag by direct mandate. It is his fifth term. Katja Dörner representing Bündnis 90/Die Grünen and Alexander Graf Lambsdorff for FDP were eleceted as well. Kelber resigned in 2019 because he was appointed Federal Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information. As Dörner was elected Lord Mayer of Bonn in September 2020, she resigned as a member of parliament after her entry into office.

Culture

Beethoven's birthplace is located in Bonngasse near the market place. Next to the market place is the Old City Hall, built in 1737 in Rococo style, under the rule of Clemens August of Bavaria. It is used for receptions of guests of the city, and as an office for the mayor. Nearby is the Kurfürstliches Schloss, built as a residence for the prince-elector and now the main building of the University of Bonn.

The Poppelsdorfer Allee is an avenue flanked by Chestnut trees which had the first horsecar of the city. It connects the Kurfürstliches Schloss with the Poppelsdorfer Schloss, a palace that was built as a resort for the prince-electors in the first half of the 18th century, and whose grounds are now a botanical garden (the Botanischer Garten Bonn). This axis is interrupted by a railway line and Bonn Hauptbahnhof, a building erected in 1883/84.

The Beethoven Monument stands on the Münsterplatz, which is flanked by the Bonn Minster, one of Germany's oldest churches.

The three highest structures in the city are the WDR radio mast in Bonn-Venusberg (180 m or 590 ft), the headquarters of the Deutsche Post called Post Tower (162.5 m or 533 ft) and the former building for the German members of parliament Langer Eugen (114.7 m or 376 ft) now the location of the UN Campus.

Churches

- Bonn Minster[19]

- Doppelkirche Schwarzrheindorf built in 1151

- Old Cemetery Bonn (Alter Friedhof), one of the best known cemeteries in Germany[20]

- Kreuzbergkirche, built in 1627 with Johann Balthasar Neumann's Heilige Stiege, it is a stairway for Christian pilgrims[21]

- St. Remigius, where Beethoven was baptized

Modern buildings

- Beethovenhalle

- Bundesviertel (federal quarter) with many government structures including

- Post Tower, the tallest building in the state North Rhine-Westphalia, housing the headquarters of Deutsche Post/DHL

- Maritim Bonn, five-star hotel and convention centre

- Schürmann-Bau, headquarters of Deutsche Welle

- Langer Eugen, since 2006 the centre of the United Nations Campus, formerly housing the offices of the members of the German parliament

- Deutsche Telekom headquarters

- T-Mobile headquarters

- Kameha Grand, five-star hotel

Museums

Just as Bonn's other four major museums, the Haus der Geschichte or Museum of the History of the Federal Republic of Germany, is located on the so-called Museumsmeile ("Museum Mile"). The Haus der Geschichte is one of the foremost German museums of contemporary German history, with branches in Berlin and Leipzig. In its permanent exhibition, the Haus der Geschichte presents German history from 1945 until the present, also shedding light on Bonn's own role as former capital of West Germany. Numerous temporary exhibitions emphasize different features, such as Nazism or important personalities in German history.[24]

The Kunstmuseum Bonn or Bonn Museum of Modern Art is an art museum founded in 1947. The Kunstmuseum exhibits both temporary exhibitions and its permanent collection. The latter is focused on Rhenish Expressionism and post-war German art.[25] German artists on display include Georg Baselitz, Joseph Beuys, Hanne Darboven, Anselm Kiefer, Blinky Palermo and Wolf Vostell. The museum owns one of the largest collections of artwork by Expressionist painter August Macke. His work is also on display in the August-Macke-Haus, located in Macke's former home where he lived from 1911 to 1914.

The Bundeskunsthalle (full name: Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland or Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany), focuses on the crossroads of culture, arts, and science. To date, it attracted more than 17 million visitors.[26] One of its main objectives is to show the cultural heritage outside of Germany or Europe.[27] Next to its changing exhibitions, the Bundeskunsthalle regularly hosts concerts, discussion panels, congresses, and lectures.

The Museum Koenig is Bonn's natural history museum. Affiliated with the University of Bonn, it is also a zoological research institution housing the Leibniz-Institut für Biodiversität der Tiere. Politically interesting, it is on the premises of the Museum Koenig where the Parlamentarischer Rat first met.[28] The Deutsches Museum Bonn, affiliated with one of the world's foremost science museums, the Deutsches Museum in Munich, is an interactive science museum focusing on post-war German scientists, engineers, and inventions.[29] Other museums include the Beethoven House, birthplace of Ludwig van Beethoven,[30] the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn (Rhinish Regional Museum Bonn),[31] the Bonn Women's Museum, the Rheinisches Malermuseum and the Arithmeum.

Nature

There are several parks, leisure and protected areas in and around Bonn. The Rheinaue is Bonn's most important leisure park, with its role being comparable to what Central Park is for New York City. It lies on the banks of the Rhine and is the city's biggest park intra muros.[32] The Rhine promenade and the Alter Zoll (Old Toll Station) are in direct neighbourhood of the city centre and are popular amongst both residents and visitors. The Arboretum Park Härle is an arboretum with specimens dating to back to 1870. The Botanischer Garten (Botanical Garden) is affiliated with the university and it is here where Titan arum set a world record.[33] The natural reserve of Kottenforst is a large area of protected woods on the hills west of the city centre. It is about 40 square kilometres (15 square miles) in area and part of the Rhineland Nature Park (1,045 km2 or 403 sq mi).[34]

In the very south of the city, on the border with Wachtberg and Rhineland-Palatinate, there is an extinct volcano, the Rodderberg, featuring a popular area for hikes. Also south of the city, there is the Siebengebirge which is part of the lower half of the Middle Rhine region. The nearby upper half of the Middle Rhine from Bingen to Koblenz is a UNESCO World Heritage Site with more than 40 castles and fortresses from the Middle Ages and important German vineyards.

Transportation

Air traffic

Named after Konrad Adenauer, the first post-war Chancellor of West Germany, Cologne Bonn Airport is situated 15 kilometres (9.3 miles) north-east from the city centre of Bonn. With around 10.3 million passengers passing through it in 2015, it is the seventh-largest passenger airport in Germany and the third-largest in terms of cargo operations. By traffic units, which combines cargo and passengers, the airport is in fifth position in Germany.[35] As of March 2015, Cologne Bonn Airport had services to 115 passenger destinations in 35 countries.[36] The airport is one of Germany's few 24-hour airports, and is a hub for Eurowings and cargo operators FedEx Express and UPS Airlines.

The federal motorway (Autobahn) A59 connects the airport with the city. Long distance and regional trains to and from the airport stop at Cologne/Bonn Airport station. Other major airports within a one-hour drive by car are Frankurt International Airport and Düsseldorf International Airport.

Rail and bus system

.jpg.webp)

Bonn's central railway station, Bonn Hauptbahnhof, serves urban (S-Bahn, U-Bahn, sharing the same network with the neighbouring city of Cologne), regional (Regionalbahn), and long-distance destinations (ICE) such as Berlin, Hamburg, Munich, Zurich, Vienna, Brussels, Amsterdam and Paris. Daily, more than 67,000 people travel via Bonn Hauptbahnhof. In late 2016, around 80 long distance and more than 165 regional trains departed to or from Bonn every day.[37][38][39] The other major railway station (Siegburg/Bonn) lies on the high-speed rail line between Cologne and Frankfurt.

The bus system of Bonn is composed of roughly 30 lines which operate on a regular basis. During peaks, buses usually run every 5 minutes; off-peak buses run every 20 minutes. Several lines offer night services, especially during the weekends. Bonn is part of the Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Sieg (Rhine-Sieg Transport Association) which is the public transport association covering the area of the Cologne/Bonn Region.

Road network

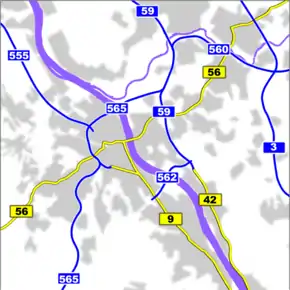

Four Autobahns run through or are adjacent to Bonn: the A59 (right bank of the Rhine, connecting Bonn with Düsseldorf and Duisburg), the A555 (left bank of the Rhine, connecting Bonn with Cologne), the A562 (connecting the right with the left bank of the Rhine south of Bonn), and the A565 (connecting the A59 and the A555 with the A61 to the southwest). Three Bundesstraßen, which have a general 100 kilometres per hour (62 miles per hour) speed limit in contrast to the Autobahn, connect Bonn to its immediate surroundings (Bundesstraßen B9, B42 and B56).

With Bonn being divided into two parts by the Rhine, three bridges are crucial for inner-city road traffic: the Konrad-Adenauer-Brücke (A562), the Friedrich-Ebert-Brücke (A565), and the Kennedybrücke (B56). In addition, regular ferries operate between Bonn-Mehlem and Königswinter, Bonn-Bad Godesberg and Niederdollendorf, and Graurheindorf and Mondorf.

Port

Located in the northern sub-district of Graurheindorf, the inland harbour of Bonn is used for container traffic as well as oversea transport. The annual turnover amounts to around 500,000 t (490,000 long tons; 550,000 short tons). Regular passenger transport occurs to Cologne and Düsseldorf.

Economy

The head offices of Deutsche Telekom, its subsidiary T-Mobile,[40] Deutsche Post, Haribo, German Academic Exchange Service, and SolarWorld are in Bonn.

Education

The Rheinische Friedrich Wilhelms Universität Bonn (University of Bonn) is one of the largest universities in Germany. It is also the location of the German research institute Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) offices and of the German Academic Exchange Service (Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst – DAAD).

Private schools

- Aloisiuskolleg, a Jesuit private school in Bad Godesberg with boarding facilities

- Amos-Comenius-Gymnasium, a Protestant private school in Bad Godesberg

- Bonn International School (BIS), a private English-speaking school set in the former American Compound in the Rheinaue, which offers places from kindergarten to 12th grade. It follows the curriculum of the International Baccalaureate.

- Libysch Schule, private Arabic high school

- Independent Bonn International School, (IBIS) private primary school (serving from kindergarten, reception, and years 1 to 6)

- École de Gaulle - Adenauer, private French-speaking school serving grades pre-school ("maternelle") to grade 4 (CM1)

- Kardinal-Frings-Gymnasium (KFG), private catholic school of the Archdiocese of Cologne in Beuel

- Liebfrauenschule (LFS), private catholic school of the Archdiocese of Cologne

- Sankt-Adelheid-Gymnasium, private catholic school of the Archdiocese of Cologne in Beuel

- Clara-Fey-Gymnasium, private Catholic school of the Archdiocese of Cologne in Bad Godesberg

- Ernst-Kalkuhl-Gymnasium, private boarding and day school in Oberkassel

- Otto-Kühne-Schule ("PÄDA"), private day school in Bad Godesberg

- Collegium Josephinum Bonn ("CoJoBo"), private catholic day school

- Akademie für Internationale Bildung, private higher educational facility offering programs for international students

- Former

- King Fahd Academy, private Islamic school in Bad Godesberg

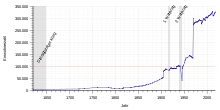

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1620 | 4,500 | — |

| 1720 | 6,535 | +45.2% |

| 1732 | 8,015 | +22.6% |

| 1760 | 13,500 | +68.4% |

| 1784 | 12,644 | −6.3% |

| 1798 | 8,837 | −30.1% |

| 1808 | 8,219 | −7.0% |

| 1817 | 10,970 | +33.5% |

| 1849 | 17,688 | +61.2% |

| 1871 | 26,030 | +47.2% |

| 1890 | 39,805 | +52.9% |

| 1910 | 87,978 | +121.0% |

| 1919 | 91,410 | +3.9% |

| 1925 | 90,249 | −1.3% |

| 1933 | 98,659 | +9.3% |

| 1939 | 100,788 | +2.2% |

| 1950 | 115,394 | +14.5% |

| 1961 | 143,850 | +24.7% |

| 1970 | 274,518 | +90.8% |

| 1987 | 276,653 | +0.8% |

| 2011 | 305,765 | +10.5% |

| 2017 | 325,490 | +6.5% |

| Population size may be affected by changes in administrative divisions. source:[41] | ||

As of 2011, Bonn had a population of 327,913. About 70% of the population was entirely of German origin, while about 100,000 people, equating to roughly 30%, were at least partly of non-German origin. The city is one of the fastest-growing municipalities in Germany and the 18th most populous city in the country. Bonn's population is predicted to surpass the populations of Wuppertal and Bochum before the year 2030.[42]

The following list shows the largest groups of origin of minorites with "migration background" in Bonn as of 31 December 2017.[43]

| Rank | Nationality | Population (31 December 2018) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8,319 | |

| 2 | 7,846 | |

| 3 | 7,218 | |

| 4 | 5,742 | |

| 5 | 3,812 | |

| 6 | 3,758 | |

| 7 | 3,165 | |

| 8 | 2,924 | |

| 9 | 2,517 | |

| 10 | 2,205 | |

| 11 | 2,065 | |

| 12 | 1,912 | |

| 13 | 1,850 | |

| 14 | 1,844 | |

| 15 | 1,762 | |

| 16 | 1,681 | |

| 17 | 1,679 | |

| 18 | 1,676 | |

| 19 | 1,664 | |

| 20 | 1,597 | |

| 21 | 1,334 | |

| 22 | 1,253 | |

| 23 | 1,200 | |

| 24 | 1,196 | |

| 25 | 1,164 | |

| 26 | 1,157 | |

Sports

Bonn is home of the Telekom Baskets Bonn, the only basketball club in Germany that owns its arena, the Telekom Dome.[44] The club is a regular participant at international competitions such as the Basketball Champions League.

The city also has a semi-professional football team Bonner SC which was formed in 1965 through the merger of Bonner FV and Tura Bonn. The Bonn Gamecocks American football team play at the 12,000-capacity Stadion Pennenfeld.

The headquarters of the International Paralympic Committee has been located in Bonn since 1999.

International relations

Since 1983, the City of Bonn has established friendship relations with the City of Tel Aviv, Israel, and since 1988 Bonn, in former times the residence of the Princes Electors of Cologne, and Potsdam, Germany, the formerly most important residential city of the Prussian rulers, have established a city-to-city partnership.

Central Bonn is surrounded by a number of traditional towns and villages which were independent up to several decades ago. As many of those communities had already established their own contacts and partnerships before the regional and local reorganisation in 1969, the Federal City of Bonn now has a dense network of city district partnerships with European partner towns.

The city district of Bonn is a partner of the English university city of Oxford, England, UK (since 1947), of Budafok, District XXII of Budapest, Hungary (since 1991) and of Opole, Poland (officially since 1997; contacts were established 1954).

The district of Bad Godesberg has established partnerships with Saint-Cloud in France, Frascati in Italy, Windsor and Maidenhead in England, UK and Kortrijk in Belgium; a friendship agreement has been signed with the town of Yalova, Turkey.

The district of Beuel on the right bank of the Rhine and the city district of Hardtberg foster partnerships with towns in France: Mirecourt and Villemomble.

Moreover, the city of Bonn has developed a concept of international co-operation and maintains sustainability oriented project partnerships in addition to traditional city twinning, among others with Minsk in Belarus, Ulaanbaatar in Mongolia, Bukhara in Uzbekistan, Chengdu in China and La Paz in Bolivia.

Twin towns – sister cities

The city of Bonn is twinned with:[45]

Bonn city district has partnerships with:

Oxford, United Kingdom, since 1947[45][47]

Oxford, United Kingdom, since 1947[45][47] Budapest, Budafok, Hungary, since 1991[45]

Budapest, Budafok, Hungary, since 1991[45] Opole, Poland, since 1997[45][48]

Opole, Poland, since 1997[45][48]

Bad Godesberg district has partnerships with:[45][49]

Saint-Cloud, France, since 1957

Saint-Cloud, France, since 1957 Frascati, Italy, since 1957

Frascati, Italy, since 1957.svg.png.webp) Kortrijk, Belgium, since 1957

Kortrijk, Belgium, since 1957 Windsor and Maidenhead, United Kingdom, since 1960

Windsor and Maidenhead, United Kingdom, since 1960

The city of Bonn also has project partnerships with:

Notable residents

Up to the 19th century

- Johann Peter Salomon, baptized 20 February 1745 † 25 November 1815 in London, musician

- Franz Anton Ries, * 10 November 1755 † 1 November 1846 in Bonn, violinist and violin teacher

- Ludwig van Beethoven, * 16 December 1770 † 26 March 1827 in Vienna, composer

- Salomon Oppenheim, Jr., * 19 June 1772 † 8 November 1828 in Mainz, banker

- Peter Joseph Lenné, * 29 September 1789 † 23 January 1866 in Potsdam, gardener and landscape architect

- Friedrich von Gerolt, * 5 March 1797 † 27 July 1879 in Linz, diplomat

- Karl Joseph Simrock, * 28 August 1802 † 18 July 1876 in Bonn, writer and specialist in German

- Wilhelm Neuland, * July 1806 † 28 December 1889 in Bonn, composer and conductor

- Johanna Kinkel, * 8 July 1810 † 15 November 1858 in London, composer and writer

- Moses Hess, * 21 June 1812 † 6 April 1875 in Paris, philosopher and writer

- Johann Gottfried Kinkel, * 11 August 1815 † 12 November 1882 in Zürich, theologian, writer, and politician

- Alexander Kaufmann, * 14 May 1817 † 1 May 1893 in Wertheim, author and archivist

- Leopold Kaufmann, * 13 March 1821 † 27 February 1898 in Bonn, mayor

- Julius von Haast, * 1 May 1822 † 16 August 1887 in Christchurch, New Zealand, professor of geology

- Dietrich Brandis, * 31 March 1824 † 28 May 1907 in Bonn, botanist

- Balduin Möllhausen, * 27 January 1825 † 28 May 1905 in Berlin, traveler and writer

- Maurus Wolter, * 4 June 1825 † 8 July 1890 in Beuron, Benedictine, founder and first abbot of the Abbey of Beuron and Beuronese Congregation

- August Reifferscheid, * 3 October 1835 † 10 November 1887 in Strasbourg, philologist

- Antonius Maria Bodewig, * 2 November 1839 † 8 January 1915 in Rome, Jesuit missionary and founder

- Nathan Zuntz, * 7 October 1847 † 23 March 1920 in Berlin, physician

- Alexander Koenig, * 20 February 1858 † 16 July 1940 in Blücherhof, Klocksin, zoologist, founder of Museum Koenig in Bonn

- Alfred Philippson, * 1 January 1864 † 28 March 1953 in Bonn, geographer

- Johanna Elberskirchen, * 11 April 1864 † 17 May 1943 in Rüdersdorf, feminist writer and activist

- Max Alsberg, * 16 October 1877 † 10 September 1933, lawyer

- Kurt Wolff, * 3 March 1887 † 21 October 1963, publisher

- Hans Riegel (senior), * 3 April 1893 † 31 March 1945, entrepreneur

- Eduard Krebsbach, * 8 August 1894 † 28 May 1947 in Landsberg am Lech, SS doctor in Nazi Mauthausen concentration camp, executed for war crimes

- Paul Kemp, * 20 May 1896 † 13 August 1953 in Bonn, actor

1900–1950

- Hermann Josef Abs, * 15 October 1901 † 5 February 1994 in Bad Soden am Taunus, board member of the Deutsche Bank

- Paul Ludwig Landsberg, * 3 December 1901 † 2 April 1944 in Sachsenhausen concentration camp, philosopher

- Heinrich Lützeler, * 27 January 1902 † 13 June 1988 in Bonn, philosopher, art historian, and literary scholar

- Helmut Horten, * 8 January 1909 † , 30 November 1987, entrepreneur

- Theodor Schieffer, * 11 June 1910 † 9 April 1992, historian and medievalist

- Irene Sänger-Bredt, * 24 April 1911 † 20 October 1983 in Stuttgart, mathematician and physicist

- Ernst Friedrich Schumacher, * 16 August 1911 † 4 September 1977 in the train between Geneva and Lausanne, economist

- Klaus Barbie, * 25 October 1913 † 25 September 1991 in Lyon, Nazi SS and Gestapo war criminal, the "Butcher of Lyon"

- Karl-Theodor Molinari, * 7 February 1915 † 11 December 1993 in Dortmund, General and founding chairman of the German Armed Forces Association

- Karlrobert Kreiten, * 26 June 1916 in Bad Godesberg † 7 September 1943 in Berlin-Plotzensee, pianist

- Hans Walter Zech-Nenntwich * 10 July 1916 in Toruń, Second Polish Republic, SS Cavalry member and war criminal

- Walther Killy (1917–1985), German literary scholar, Der Killy

- Hannjo Hasse, * 31 August 1921 † 5 February 1983 in Falkirk, actor

- Walter Gotell, * 15 March 1924 † 5 May 1997 in London, actor

- Walter Eschweiler, born 20 September 1935, football referee

- Alexandra Cordes, * 16 November 1935 † 27 October 1986 in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, writer

- Joachim Bißmeier, born 22 November 1936, actor

- Roswitha Esser, born 18 January 1941, canoeist, gold medal winner at the Olympic Games in 1964 and 1968, Sportswoman of the Year 1964

- Heide Simonis, born 4 July 1943, politician (SPD), former Prime Minister of Schleswig-Holstein, since 2005 honorary chairman of UNICEF Germany

- Paul Alger, born 13 August 1943, football player

- Johannes Mötsch, born 8 July 1949, archivist and historian

- Klaus Ludwig, born 5 October 1949, race car driver

1951 to present

- Günter Ollenschläger, born 3 March 1951 in Beuel, medical and science journalist

- Hans "Hannes" Bongartz, born 3 October 1951, football player and coach

- Christa Goetsch, born 28 August 1952, politician (Alliance '90 / The Greens)

- Thomas de Maizière, born 21 January 1954, politician (CDU), former Minister of Defence and of the Interior

- Gerd Faltings, born 28 July 1954, mathematician, Fields Medal winner

- Olaf Manthey, born 21 April 1955, former touring car racing driver

- Michael Kühnen, * 21 June 1955 † 25 April 1991 in Kassel, Neo-Nazi

- Roger Willemsen, * 15 August 1955 † 7 February 2016 in Wentorf, publicist, author, essayist, and presenter

- Norman Rentrop, born 26 October 1957, publisher, author, and investor

- Markus Maria Profitlich, born 25 March 1960, comedian and actor

- Guido Westerwelle, * 27 December 1961 † 8 March 2016, politician (FDP), Foreign Minister and Vice Chancellor of Germany from 2009 to 2011

- Mathias Dopfner, born 15 January 1963, chief executive officer of Axel Springer AG

- Nikolaus Blome, born 16 September 1963, journalist

- Maxim Kontsevich, born 25 August 1964, mathematician, Fields Medal winner

- Johannes B. Kerner, born 9 December 1964, TV presenter, Abitur at the Aloisiuskolleg, and studied in Bonn

- Anthony Baffoe, born 25 May 1965 football player, sports presenter, and actor

- Sonja Zietlow, born 13 May 1968, TV presenter

- Burkhard Garweg, born 1 September 1968, member of the Red Army Faction

- Sabriye Tenberken, born 19 September 1970, Tibetologist, founder of Braille Without Borders

- Thorsten Libotte, born 20 July 1972, writer

- Tamara Gräfin von Nayhauß, born 23 July 1972, television presenter

- Silke Bodenbender, born 31 January 1974, actress

- Juli Zeh, born 30 June 1974, writer

- Oliver Mintzlaff, born 19 August 1975, track and field athlete and sports manager, CEO of RB Leipzig

- Markus Dieckmann, born 7 January 1976, beach volleyball player

- Bernadette Heerwagen, born 22 June 1977, actress

- Melanie Amann, born 1978, journalist

- Bushido, born 28 September 1978, musician and rapper

- Sebastian Stahl, born 20 September 1978, race car driver

- Sonja Fuss, born 5 November 1978, football player

- Andreas Tölzer, born 27 January 1980, judoka

- Jens Hartwig, born 16 April 1980, actor

- Natalie Horler, born 23 September 1981, front woman of the Dance Project Cascada

- Marcel Ndjeng, born 6 May 1982, football player

- Marc Zwiebler, born 13 March 1984, badminton player

- Benjamin Barg, born 15 September 1984, football player

- Alexandros Margaritis, born 20 September 1984, race car driver

- Ken Miyao, born 16 March 1986, pop singer

- Julia Reda, born 30 November 1986, politician

- Peter Scholze, born 11 December 1987, mathematician, Fields Medal winner

- Célia Okoyino da Mbabi, born 27 June 1988, football player

- Luke Mockridge, born 21 March 1989, comedian and author

- Pius Heinz, born 4 May 1989, poker player, 2011 WSOP Main Event champion

- Jonas Wohlfarth-Bottermann, born 20 February 1990, basketball player

- Levina, born 1 May 1991, singer

- Bienvenue Basala-Mazana, born 2 January 1992, football player

- Annika Beck, born 16 February 1994, tennis player

- James Hyndman, born 23 April 1962, stage actor

- Konstanze Klosterhalfen, born 18 February 1997, track and field athlete

References

- "Bevölkerung der Gemeinden Nordrhein-Westfalens am 31. Dezember 2019" (in German). Landesbetrieb Information und Technik NRW. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Anthony James Nicholls (1997). The Bonn Republic: West German Democracy, 1945–1990. Longman. ISBN 9780582492318 – via Google Books.

- tagesschau.de. "Bonn-Berlin-Gesetz: Dieselbe Prozedur wie jedes Jahr". tagesschau.de (in German). Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- Cowell, Alan (23 June 2011). "In Germany's Capitals, Cold War Memories and Imperial Ghosts". The New York Times.

- Bundestag, Deutscher. "Deutscher Bundestag: Berlin-Debatte / Antrag Vollendung der Einheit Deutschlands, Drucksache 12/815". webarchiv.bundestag.de (in German). Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Amt, Auswärtiges. "Übersicht: Die Vereinten Nationen (VN) in Deutschland". Auswärtiges Amt (in German). Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- "UNBonn.org".

- "Wohnberechtigte Bevölkerung in der Stadt Bonn am 31.12.2014". Bonn.de (in German). Stadt Bonn. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- "Average Temperature, weather by month, Bonn weather averages". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- Stanton, Shelby L. (2006). World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division, 1939–1946 (Revised ed.). Stackpole Books. p. 76. ISBN 9780811701570.

- Caborn, Joannah (2006). Schleichende Wende. Diskurse von Nation und Erinnerung bei der Konstituierung der Berliner Republik (in German). Unrast Verlag. p. 12. ISBN 9783897717398 – via Google Books.

- Barbara Marshall (18 December 1996). Willy Brandt: a Political Biography. Springer. p. 149. ISBN 9780230390096.

- "Bonn to Berlin move still controversial". The Local. 15 June 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Sebastian Lentz (17 June 2011). "Nationalatlas aktuell". Hauptstadtbeschluss. Archived from the original on 31 March 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- Laux, Hans-Dieter (1991). "Berlin oder Bonn? Geographische Aspekte eine Parlamentsentscheidung". Geographische Rundschau (in German). 43 (12): 740–743.

- Thompson, Wayne C. (2008). The World Today Series: Nordic, Central and Southeastern Europe 2008. Harpers Ferry, West Virginia: Stryker-Post Publications. ISBN 978-1-887985-95-6.

- "Rat. Ausschüsse". Bundesstadt Bonn (in German). Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- Germany, RP Media. "Bonn wird grün - Katja Dörner gewinnt Stichwahl". rp-online.de. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- "Das Bonner Münster @ Kirche in der City". Bonner-muenster.de. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- de:Alter Friedhof Bonn

- de:Kreuzbergkirche

- "Bonn Region – Sightseeing – Fortresses and castles – Godesburg mit Michaelskapelle (Fortress Godesburg with St. Michael Chapel)". 25 May 2005. Archived from the original on 25 May 2005. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- de:Godesburg

- "Stiftung Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Home". Hdg.de. 13 June 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- "Kunstmuseum Bonn – Overview". Kunstmuseum.bonn.de. n.d. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- "MUSEUMSMEILE BONN". museumsmeilebonn.de (in German). Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- "Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany – Bonn – English Version". Kah-bonn.de. Archived from the original on 9 May 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- de:Museum Koenig

- "MUSEUMSMEILE BONN". museumsmeilebonn.de (in German). Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- Fraunhofer-Institut für Medienkommunikation IMK (26 March 2002). "Beethoven digitally". Beethoven-haus-bonn.de. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- de:Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn

- de:Freizeitpark Rheinaue

- de:Botanischer Garten Bonn

- de:Kottenforst

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Sommerflugplan 2015: Sieben neue Ziele ab Flughafen Köln/Bonn". airliners.de. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- "Sanierung geht in die heiße Phase". General-Anzeiger. 4 November 2016. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016.

- Bettina Köhl (12 May 2017). "Der Hauptbahnhof Bonn wird saniert" [Bonn Central Station is being renovated]. General-Anzeiger (in German). Archived from the original on 1 December 2020.

- "Schöne Aussichten im Hauptbahnhof Bonn". Deutsche Bahn. 4 November 2016. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016.

- "Deutsche Telekom facts and figures". T-Mobile. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2009.

- Link

- "IHK Bonn/Rhein-Sieg: Bonn wächst weiter". 29 November 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- "Eckzahlen der aktuellen Bevölkerungsstatistik (Stichtag 31.12.2017)". www2.bonn.de. Statistikstelle der Bundesstadt Bonn. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- "Telekom Baskets Bonn – Telekom Dome – Übersicht" Archived 12 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Telekom-Baskets-Bonn.de. Retrieved 8 March 2014. (in German)

- "City Twinnings". Stadt Bonn. Archived from the original on 10 April 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- "Die Partnerstädte der Landeshauptstadt Potsdam". potsdam.de (in German). Archived from the original on 25 June 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- "Oxford's International Twin Towns". Oxford City Council. Archived from the original on 17 August 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- "Opole Official Website – Twin Towns". Urząd Miasta Opola. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- Bonn, Bundesstadt. "Stadt Bonn – Städtepartnerschaft". bonn.de (in German). Archived from the original on 14 December 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- "Cape Coast signs sister-city partnership with Bonn". Ghana News Agency (GNA). 13 April 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "Twin towns and Sister cities of Minsk [via WaybackMachine.com]" (in Russian). The department of protocol and international relations of Minsk City Executive Committee. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2013.