Amarna Tomb 3

Amarna Tomb 3 is a rock-cut cliff tomb located in Amarna, Upper Egypt. The tomb belonged to the Ancient Egyptian noble Ahmes (Ahmose), who served during the reign of Akhenaten.[1] The tomb is situated at the base of a steep cliff and mountain track at the north-eastern end of the Amarna plains.[2] It is located in the northern side of the wadi that splits the cluster of graves known collectively as the Northern tombs.[3] Amarna Tomb 3 is one of six elite tombs belonging to the officials of Akhenaten.[4] It was one of the first Northern tombs, built in Year 9 of the reign of Akhenaten.[5]

| Amarna Tomb 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Burial site of Ahmose | |||

Tomb of Ahmose | |||

Amarna Tomb 3 | |||

| Coordinates | 27°38′43″N 30°53′47″E | ||

| Location | Tombs of the Nobles | ||

| Discovered | Open in antiquity | ||

| Layout | Cruciform Plan | ||

The Northern Tombs were first mapped and examined by Egyptologist John Gardiner Wilkinson in the early 1800s. The first comprehensive survey of Amarna Tomb 3 was performed by French Egyptologist Nestor L’Hôte in 1839.[6] L’Hôte made castings and copies of the reliefs within the tomb, contributing to contemporary analysis of the site as many of these images are no longer visible. The tomb of Ahmose provides insight into elite Egyptian burial customs and funerary architecture in the New Kingdom period.

Ahmose

| Ahmose in hieroglyphs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

iˁḥ-ms[7] Born of Iah | ||||||

Steward of Akhenaten, Sealbearer of the King of Lower Egypt, Fanbearer at the right hand of the King, etc | ||||||

Epithets inscribed within the tomb record Ahmose's official titles as an administrator of the palace. These included "Veritable Scribe of the King", "Fan-bearer on the right hand of the King", "Superintendent of the Court House", "Steward of the House of Akhenaten", "Royal Chancellor", "Sole Companion and First of the Companions", and "Follower of the feet of the Lord of the Two Lands”.[3] The hymns in the tomb state that Ahmose began working for Akhenaten as a youth, and served him until old age. The inscriptions also demonstrate that Ahmose had a son, Nefer-kheperu-ra. Other than this brief background, no information on the life of Ahmose is available.

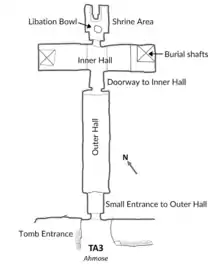

Layout of tomb

Amarna Tomb 3 is a symmetrical cruciform-plan tomb consisting of two rectangular halls and a shrine.[5] The sepulchre is located a short distance from the Tomb of Meryra, a High Priest. The entrance to the tomb looks on to the south-western part of the Amarna plains. The facade of the tomb consists of a simple doorframe of recessed rock which is decorated with hymns and prayers to the god Aten.[8] A three-sided, walled, brick courtyard is located at the front of the tomb’s entrance.[5] The lintel and jambs of the exterior door contain prayer inscriptions to the Pharaoh Akhenaten.[9] After passing through the doorway, a smaller decorated entrance leading towards the outer hall is reached. Remnants of colour indicate that painted designs once adorned the ceiling and walls of this entryway.[3] The outer hall consists of a deep rectangular chamber with plastered walls and a vaulted roof.[8] A corniced doorway leads towards the inner hall. The inner hall is positioned at a right angle to the outer hall, containing two burial shafts at either end. The first burial shaft measures approximately thirty feet deep.[8]

The inner hall leads to the back of the tomb, where the shrine area is located. The uppermost segment of the lintel of the shrine's doorway is decorated with a carving of the uraeus.[5] The lower portion shows unfinished carvings of a line of Djed-pillars.[10] The shrine houses an unfinished and disfigured limestone statue of Ahmose. In this statue-niche, the figure of Ahmose is seated, a characteristic pose of Egyptian burial sculpture which symbolises a willingness to receive offerings.[11] The empty recesses of the stone statue once consisted of coloured decorative elements carved out of faience.[10] A shallow libation bowl is carved in the floor at the foot of the statue, used for religious offerings to the gods.[5] The shrine area was closed off by wooden folding doors. The side wall of the statue-niche was cut in a perfect square, demonstrating expertise in stone masonry.[5] Throughout the tomb, the undecorated walls are mostly covered in Greek graffiti, which was scratched into the plaster.

Tomb decoration

Outer wall: Ahmes in prayer

The outer wall of the tomb depicts two images of Ahmose wearing the traditional dress of an Egyptian noble. The scenes and texts have suffered a lot of damage, but early copies show that Ahmose was depicted on both sides of the entrance on the wall thickness.[3] He is clothed in a long robe with a decorated sash tied around the waist, laced sandals, a long, straight wig, a tall headdress and a gold necklace.[3] Ahmose is pictured in adoration of the cartouche of Aten and adorned with the symbol of the Pharaoh.[12] In the images, Ahmose holds ritual objects which demonstrate his official role within the palace. He holds a fan, an object connected to his duty as “the fan bearer at the right hand of the king’”.[9] He is pictured with an Egyptian battle-axe, referring to his position in the military.[3] The fan and an axe are tied together, secured to a strap and carried over his shoulder.[13] This scene is accompanied by prayers of Ahmose which pay respect to the god Aten and the royal family. Ahmose’s prayers for his own family’s prosperity, in particular for his son Nefer-kheperu-ra,[3] are presented alongside these inscriptions.

Upper west wall: A royal visit to the Temple of Aten

This partly preserved bas-relief sculpture depicts a royal visit to the temple of Aten by the King and his consort. The royal family are shown in a horse-drawn chariot accompanied by a military escort.[12] Akhenaten wears a Khepresh crown, while Nefertiti is shown wearing her flat topped blue crown. The four rows of soldiers are led by a trumpeter. These troops are fronted by a row of soldiers with spears, and followed by officers wielding sickle-swords and batons.[3] Egyptologist Norman de Garis Davies stated that the accuracy of the military formation within this relief was indicative of Ahmose's military experience.[3] The army is diverse, composed of Egyptian and foreign troops, distinguished by their different hairstyles and military accessories. The Nubian bowmen are illustrated with shaved heads and gold earrings while the Libyan archers are drawn with a feather in their hair. The pointed beards characterise the Syrian officers holding spears.[8] This military imagery contributed to the warrior-pharaoh image of King Akhenaten, which is also present in the noble tombs of Panehesy, Mahu, and Meryre I.[14] The depiction of the royal chariot is outlined with red paint, a remnant of the relief’s original draft work. As the chariot approaches the temple, the royal entourage is received by religious officials, who are depicted offering cattle and other sacred animals to the royal family. A small architectural model of the temple layout is located on the left side of the carving. This artistic representation of the temple provides insight into New Kingdom religious architecture. The temple comprises royal statues, a sacrificial altar, a chapel, a sacrificial butcher house, an altar holding the benben stone and an outdoor courtyard.[8] The right part of the relief has not survived.[3]

Lower west wall: The royal family at home

This scene depicts a royal banquet in the hall of the palace. In Ancient Egyptian tomb decoration, banquet scenes were used as a show of elitism and grandeur. Banquet tomb scenes held religious significance as they signified a connection between the living and the deceased through the offering of food and drink.[15] In the relief, elite guests are waited on by servants and entertained by musicians playing the bow-harp and the lute.[14] The King and Queen are seated on high, throne-like chairs. Sun rays pierce the roof of the hall and settle upon Akhenaten and his wife Nefertiti, emphasising the connection of the royal family to the sun-god Aten.[3] Ahmose is bowed, attending King Akhenaten and Queen Nefertiti as they eat various meats.[14] Akhenaten is shown seated eating what appears to be a roasted duck. Behind him we see Nefertiti seated with one of the princesses on her lap. She is holding a cut of meat. Next to Nefertiti we see two more princesses seated on chairs. This scene may have been included to show Ahmose in his role as the Steward to Akhenaten.[3] Akhenaten, Nefertiti and their daughters are depicted on a much larger scale than Ahmose, an example of the ancient art convention of hierarchical proportion. More servants attend the King and Queen, including a cupbearer holding a drinking goblet, a group of nursemaids and a band of entertainers.[3]

Inscriptions

Exterior door posts

Although the inscriptions on the exterior jambs of the door have been badly mutilated, fragments of Ahmose’s hymns are still legible.[1] The hymns on the external door posts concern the praise of the King Akhenaten, his receiving of offerings and his ability to grant eternal life for his steward Ahmose. The inscriptions are written in a conventional offering formula for funerary hymns called the “King’s Formula”,[16] composed in the structure: “an offering (or: boon) which the King has given…”.[16] One of the hymns on the left side of the door post expresses Ahmose’s desire for his soul to live on in the palace of the King: “A boon [offering] which the king gives of Hor-Aten and Neferkheprure-Waenre [King Akhenaton]: may he grant entry and exit in the king’s house, limbs being filled with joy everyday. For the Ka of the true king’s scribe, overseer of the front hall and steward of the House of Akhenaten, long in his lifetime, Ahmose”.[9] The following hymns are repetitive and retain this same structure, further stating the feelings of “happiness, joy and exultation”,[9] and the offerings of food which the King bestowed upon Ahmose.

Exterior lintel

The inscription on the lintel of the outer door is almost identical to the hymn on the exterior doorframe of Amarna Tomb 5.[9] The funerary hymns within the Tombs of the Nobles are noticeably similar, demonstrating an adherence to kingly and religious epigraphic conventions. This inscription offers a short prayer to the god Aten and King Akhenaten. Ahmose presents more of his noble titles within this hymn, including the “Royal Chancellor”, “the Sole Companion”, and the “possessor of reward”.[3]

Thickness of east wall: “Hymn to the Setting Sun”

The “Hymn to the Setting Sun” is an adoration to the sun-god Aten, depicting his creation of the world and solidification of peace between Upper and Lower Egypt - “in the peace of the two lands”.[1] The hymn states that Aten allowed Ahmose to dutifully serve the king everyday and granted him a “goodly burial after old age in the cliff of Akhenaten”.[3] This hymn provides details regarding the life of Ahmose, of which we have little information. From this inscription, we see that he lived to experience old age and attended the Pharaoh until his death. The hymn states that Ahmose began attending Akhenaten from a young age - “he [Akhenaten] fostered me when I was a youth until I attained honoured old age…”.[3] This inscription demonstrates the religious reformation under Akhenaten, moving from the worship of Amun to the monotheistic cult of the sun-god Aten, a religion known as Atenism. According to Professor James K. Hoffmeier, the hymns to Aten which appear within the Northern Tombs at Amarna reflected “Atenism’s ultimate expression” and “religious revolution”.[17] The “Hymn to the Setting Sun” and “Rising Sun” in the tomb of Ahmose resemble the Great Hymn to Aten inscribed on the west well of the tomb of the noble Ay, Southern Tomb 25.[18]

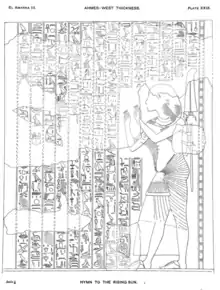

Thickness of west wall: “Hymn to the Rising Sun”

The inscription on the west wall of Amarna Tomb 3 is a prayer to the god Ra-Horakhty,[3] the combination of the gods Ra, the sun god, and Horus, the god of the sky and horizon. Like the “Hymn to the Setting Sun”, this inscription covers the creation of mankind and animals by the god Ra. This inscription is primarily concerned with the health and prosperity of Ahmose’s “beloved son, Nefer-kheperu-ra”.[3] Ahmose prays for his son’s wellbeing and success, calling on the god to “grant to him Sed festivals”, a celebration of Pharaonic rule and kingly power, “years of peace” and a “burial of his giving”.[3] Egyptologist Jan Assman stated that inscriptions of sun hymns in tombs became an established practice during the New Kingdom period.[19] He commented that the presentation of these hymns in burial contexts was a “fulfilment of a prescribed norm”,[19] not a reflection of individual religious piety. According to Assman, the sun hymns in the tomb of Ahmose are based upon a standard funerary text belonging to the cult of Aten.[19]

Greek graffiti

Fifty-nine instances of Greek graffiti have been scratched into the lower plaster of the tomb’s corridors.[8] The graffiti was discovered in 1835 by Sir John Gardiner Wilkinson.[3] Barry Kemp, the Director of Excavations at Amarna, has stated that this graffiti can be dated to the Ptolemaic Period.[20] The graffiti records the messages and names of the tomb's visitors, most of which are presumed to have been soldiers. A graffito in the corridor records a message from a Greek visitor; “I come. Year 37”.[3] The most well-known Greek graffito from the tomb is located next to the exterior door frame of the tomb. The inscription reads: “having ascended here, Catullinus has engraved this in the doorway, marvelling at the art of the holy quarriers”.[3] This graffito provides insight into later Greek perspectives on the art, technology and architecture of the Ancient Egyptians. Another message is a Coptic Christian graffito, providing evidence for the coptic occupation of the site.[21] Coptic Christians coopted the site of the North Tombs in the fifth and sixth centuries AD.[20] They inhabited the tomb of Ahmose, as evidenced by two low exterior walls which were built by later settlers.[22]

References

- Breasted, James Henry (1906). Ancient Records of Egypt, Vol II (PDF). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 413–414.

- "North Tombs - Amarna The Place - Amarna Project". www.amarnaproject.com. Retrieved 2020-09-29.

- Davies, Norman de Garis (1903). The Rock Tombs of El-Amarna. London: Egypt Exploration Society. pp. 4–33.

- Stevens, Anna (2016). "Tell el-Amarna". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology.

- Badawy, Alexander (1968). A History of Egyptian Architecture. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 422–427.

- "The Amarna Discovery Timeline". AMARNA:3D. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- Ranke, Hermann (1935). Die Ägyptischen Personennamen, Bd. 1: Verzeichnis der Namen (PDF). Glückstadt: J.J. Augustin. p. 12. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- The Amarna Project. Guide Book to the North Tombs (PDF). The Amarna Trust. p. 8.

- Murnane, William J. (1995). Texts from the Amarna Period in Egypt. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press. pp. 120–122.

- The Amarna Trust (2014). Horizon: The Amarna Project and Amarna Trust Newsletter, vol. 14. pp. 7-8. https://www.amarnaproject.com/documents/pdf/horizon-newsletter-14.pdf

- Watts, Edith W. (1998). The Art of Ancient Egypt, A Resource for Educators. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art Publications. p. 37.

- Porter, Bertha; Moss, Rosalind (1934). Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings, IV. Lower and Middle Egypt. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. p. 214.

- Kemp, Barry (2012) The City of Akhenaten and Nefertiti: Amarna and its People, Thames and Hudson, p. 111.

- Clifton, Rebecca (2019). Art and Identity in the Age of Akhenaten. Melbourne, VIC: University of Melbourne. pp. 149-265.

- Khalifa, Sherif Shaban (2014). "Banquets in Ancient Egypt". Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology. 2: 474.

- Franke, Detlef (2003). "The Middle Kingdom Offering Formulas: A Challenge". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 89: 39–57. doi:10.1177/030751330308900104. S2CID 159578775.

- Hoffmeier, James K (2015). Akhenaten and the Origins of Monotheism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 213.

- "Amarna Belief". www.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- Assman, Jan (1994). Egyptian Solar Religion in the New Kingdom: Re, Amun and the crisis of polytheism. London, UK: Kegan Paul International. pp. 1–2.

- Kemp, Barry (2013). "The Rock Tombs of Amarna". The Akhenaten Sun. The Amarna Research Foundation. 19: 8.

- Jones, Michael (1991). "The Early Christian Sites at Tell El-Amarna and Sheikh Said". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 77: 129–144. doi:10.1177/030751339107700111. S2CID 193602882.

- Sigl, Johanna (2011). "Weaving Copts in the North Tombs of Tell el-Amarna". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. 40: 357–386. ISSN 0340-2215. JSTOR 41812325.

External links

- UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology

- The Amarna Project In-depth information about current excavation and research at Amarna.

- The Archaeology of Amarna by Dr Anna Stevens. Provides a comprehensive overview of the modern and historic excavation of Amarna.

- History of Research at Amarna