Ambigram

An ambigram is a calligraphic design that has several interpretations as written.[1]

Etymology

The word ambigram was coined by Douglas Hofstadter, an American scholar of cognitive science, best known as the Pulitzer Prize winning author of the book Gödel, Escher, Bach.

An ambigram is a visual pun of a special kind: a calligraphic design having two or more (clear) interpretations as written words. One can voluntarily jump back and forth between the rival readings usually by shifting one’s physical point of view (moving the design in some way) but sometimes by simply altering one’s perceptual bias towards a design (clicking an internal mental switch, so to speak). Sometimes the readings will say identical things, sometimes they will say different things.[1]

Hofstadter describes an ambigram as a "calligraphic design that manages to squeeze two different readings into the selfsame set of curves."

Different ambigram artists (sometimes called ambigramists) may create distinctive ambigrams from the same words, differing in both style and form.

History

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_-_comics_The_Upside_Downs_of_Little_Lady_Lovekins_and_Old_Man_Muffaroo_-_At_the_house_of_the_writing_pig.jpg.webp)

Although the term is recent, the existence of mirror ambigrams has been attested since at least the first millennium. They are generally palindromes stylized to be visually symmetrical.

In ancient Greek, the phrase "νιψον ανομηματα μη μοναν οψιν" (wash the sins, not only the face), is a palindrome[3] found in several locations, including the site of the church Hagia Sophia,[2] in Istanbul, Turkey. It is sometimes turned into a mirror ambigram when written in capital letters with the removal of spaces, and the stylization of the letter N (Ͷ).

The first sator square palindrome was found in the ruins of Pompeii, that means it was created before 79 AD. A sator square using the mirror writing for the representation of the letters S and N was carved in a stone wall in Oppède (France) between the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages [4]

A boustrophedon is a type of bi-directional text, mostly seen in ancient manuscripts and other inscriptions. Every other line of writing is flipped or reversed, with reversed letters. Rather than going left-to-right as in modern European languages, or right-to-left as in Arabic and Hebrew, alternate lines in boustrophedon must be read in opposite directions. Also, the individual characters are reversed, or mirrored. It was a common way of writing in stone in Ancient Greece.

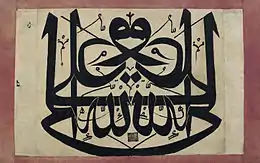

Mirror writing in Islamic calligraphy flourished during the early modern period, but its origins may stretch as far back as pre-Islamic mirror-image rock inscriptions in the Hejaz.

The earliest known non-natural rotational ambigram dates to 1893 by artist Peter Newell. Although better known for his children's books and illustrations for Mark Twain and Lewis Carroll, he published two books of reversible illustrations, in which the picture turns into a different image entirely when flipped upside down. The last page in his book Topsys & Turvys contains the phrase THE END, which, when inverted, reads PUZZLE. In Topsys & Turvys Number 2 (1902), Newell ended with a variation on the ambigram in which THE END changes into PUZZLE 2.

In March 1904 the Dutch-American comic artist Gustave Verbeek used ambigrams in three consecutive strips of The UpsideDowns of old man Muffaroo and little lady Lovekins.[5] His comics were ambiguous images, made in such a way that one could read the 6 panel comic, flip the book and keep reading. In The Wonderful Cure of the Waterfall[6] (13 March 1904) an indian medicine man says 'Big waters would make her very sound', while when flipped the medicine man turns into an Indian woman who says 'punos dery, eay apew poom, serlem big'.[7] Which is explained as, 'poor deary' several foreign words that meant that she would call the 'Serlem Big'. The next comic called At the House of the Writing Pig (20 March 1904), where two ambigram word balloons are featured. The first features an angry pig trying to make the main protagonist leave by showing a sign that says; 'big boy go away, dis am home of mr h hog', up side down it reads 'Boy yew go away. We sip. Home of hog pig.'.[8] The protagonist asks the pig if it wants a big bun, upon which it replies 'Why big buns? Am mad u!', which flips into 'In pew we sang big hym'.[9] Finally in The Bad Snake and the Good Wizard[10] (1904 Mar 27) there are two more ambigrams. The first turns 'How do you do' into the name of a wizard called 'Opnohop Moy', the second features a squirrel telling the protagonist 'Yes further on' only to inform it that there are 'No serpents here' on his way back.[11] These ambigrams are all relatively simple compared to contemporary designs, but given the constraints that Verbeek had due to the drawing and story they are impressive nevertheless. In a 2012 Swedish remake of the book,[12] the artist Marcus Ivarsson redraws The Bad Snake and the Good Wizard in his own style. He removes the squirrel, but keeps the other ambigram. 'How do you do' is replaced by 'Nejnej' (Swedish for no no) and the wizard is now called 'Laulau'.

From June to September 1908, the British monthly The Strand published a series of ambigrams by different people in its "Curiosities" column.[13] Of particular interest is the fact that all four of the people submitting ambigrams believed them to be a rare property of particular words. Mitchell T. Lavin, whose "chump" was published in June, wrote, "I think it is in the only word in the English language which has this peculiarity," while Clarence Williams wrote, about his "Bet" ambigram, "Possibly B is the only letter of the alphabet that will produce such an interesting anomaly."[13]

Rotational faces as optical illusion are very old, since metal coins with reversible figures were produced in 1550, and maybe earlier. In this perspective, a 180° rotational ambigram "¡OHO!" was published in 1946 for the cover of a book gathering reversible drawings by Rex Whistler.

Popularity

In 1969, Raymond Loewy designed the rotational New Man ambigram logo,[14][15] which is still in use in 2020.[16] The mirror ambigram DeLorean Motor Company logo was first used in 1975.[17][18]

John Langdon and Scott Kim also each believed that they had invented ambigrams in the 1970s.[19] Langdon and Kim are probably the two artists who have been most responsible for the popularization of ambigrams. John Langdon produced the first mirror image logo "Starship" in 1975.[20] Robert Petrick, who designed the invertible Angel logo in 1976,[21] was also an early influence on ambigrams.

The earliest known published reference to the term ambigram was by Hofstadter, who attributed the origin of the word to conversations among a small group of friends during 1983–1984. The original 1979 edition of Hofstadter's Gödel, Escher, Bach featured two 3-D ambigrams on the cover.

Ambigrams became more popular as a result of Dan Brown incorporating John Langdon's designs into the plot of his bestseller, Angels & Demons, and the DVD release of the Angels & Demons movie contains a bonus chapter called "This is an Ambigram". Langdon also produced the ambigram that was used for some versions of the book's cover.[19] Brown used the name Robert Langdon for the hero in his novels as an homage to John Langdon.[22]

In music, the Grateful Dead have used ambigrams several times, including on their albums Aoxomoxoa and American Beauty.

In the first series of the British show Trick or Treat, the show's host and creator Derren Brown uses cards with rotational ambigrams. These cards can read either 'Trick' or 'Treat'.

Although the words spelled by most ambigrams are relatively short in length, one DVD cover for The Princess Bride movie creates a rotational ambigram out of two words: "Princess Bride," whether viewed right side up or upside down.[23]

In 2015 iSmart's logo on one of its travel chargers went viral because the brand's name turned out to be a natural ambigram that read "+Jews!" upside down. The company noted that "...we learned a powerful lesson of what not to do when creating a logo.” [24]

Types

Ambigrams are exercises in graphic design that play with optical illusions, symmetry and visual perception. Some ambigrams feature a relationship between their form and their content. Ambigrams usually fall into one of several categories:

- 3-Dimensional

- A design where an object is presented that will appear to read several letters or words when viewed from different angles. Such designs can be generated using constructive solid geometry.

- Chain

- A design where a word (or sometimes words) are interlinked, forming a repeating chain. Letters are usually overlapped meaning that a word will start partway through another word. Sometimes chain ambigrams are presented in the form of a circle.[25]

- Dihedral

- A natural mirror-image ambigram consisting of numerical digits.

- Figure-ground

- A design in which the spaces between the letters of one word form another word.[25]

- Fractal

- A version of space-filling ambigrams where the tiled word branches from itself and then shrinks in a self-similar manner, forming a fractal. See Scott Kim's fractal of the word "TREE" for an animated example.[26]

- Mirror-image

- A design that can be read when reflected in a mirror, usually as the same word or phrase both ways. Ambigrams that form different words when viewed in the mirror are also known as glass door ambigrams, because they can be printed on a glass door to be read differently when entering or exiting.[25]

- Multi-Lingual

- An ambigram that can be read one way in one language and another way in a different language. Multi-lingual ambigrams can exist in all of the various styles of ambigrams, with multi-lingual perceptual shift ambigrams being particularly striking. The name sinosign has been proposed for the case of the shift being between Latin script and Chinese script.

- Natural

- A natural ambigram is a word that possesses one or more of the above symmetries when written in its natural state, requiring no typographic styling. For example, the words "dollop", "sos", "SᙡIᙢS", "suns" and "pod" form natural rotational ambigrams. In Korean, 곰 (bear) and 문 (door) form a natural rotational ambigram. In some fonts, the word "seas" forms a natural rotational ambigram. The word "bud" forms a natural mirror ambigram when reflected over a vertical axis, as does "ليبيا", the name of the country Libya in Arabic. The words "BOX", "CHOICE" and "OXIDE", in all capitals, form natural mirror ambigrams when reflected over a horizontal axis. The longest such word is CHECKBOOK. The words "HIM", "TOOTH", "MAXIMUM", "TOY" and "WHOM", in all capitals, forms natural mirror ambigrams when their letters are stacked vertically and reflected over a vertical axis. See the article transformation of text for a discussion of letter symmetry.

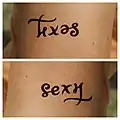

- Perceptual Shift (Oscillation)

- A design with no symmetry but can be read as two different words depending on how the curves of the letters are interpreted.[25]

- Rotational

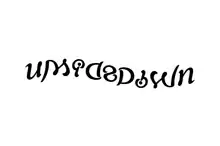

- A design that presents several instances of words when rotated through a fixed angle. This is usually 180 degrees, but rotational ambigrams of other angles exist, for example 90 or 45 degrees. The word spelled out from the alternative direction(s) is often the same, but may be a different word to the initially presented form. A simple example is the lower-case abbreviation for "Down", dn, which looks like the lower-case word up when rotated 180 degrees.

- Strobogrammatic

- A natural rotational ambigram consisting of numerical digits.

- Space-Filling

- Similar to chain ambigrams, but tile to fill the 2-dimensional plane.

- Spinonym

- An ambigram in which all the letters are made of the same glyph, possibly rotated and/or inverted. WEB is an example of a word that can easily be made into a spinonym. Previously called rotoglyphs or rotaglyphs.[27]

- Symbiotogram

- An ambigram that, when rotated, can be read as a different word than the original, e.g., "LIFE" would read as "DEATH".[28]

Totem

An ambigram whose letters are stacked. May be rotational or mirrored.

Creating ambigrams

Handmade designs

There are no universal guidelines for creating ambigrams, and there are different ways of approaching problems. A number of books suggest methods for creation (including WordPlay[29] and Eye Twisters[30]).

Ambigram generators

Computerized methods to automatically create ambigrams have been developed. Most of them function on the simplified principle of mapping a single letter to another single letter. Because of this weakness, most of them can only map a word to itself or to another word that is the same length and do not combine letters. Thus, the generated ambigrams are in general of poor quality when compared to hand made ambigrams. More sophisticated techniques employ databases of thousands of curves to create complex ambigrams. Most ambigram generators are free, while some others require payment.

Other names

Ambigrams have also been called, among other things:

- vertical palindromes (1965)[31]

- designatures (1979)[32]

- inversions (1980)[33]

Gallery

.gif) Ambigram "Ambigram / Wikipedia", 180° rotational symmetry.

Ambigram "Ambigram / Wikipedia", 180° rotational symmetry. Rotational ambigram, "Say Yes".

Rotational ambigram, "Say Yes". Three-dimensional ambigram, ABC.

Three-dimensional ambigram, ABC. Perceptual shift ambigram, Wave and Particle, by Douglas Hofstadter.

Perceptual shift ambigram, Wave and Particle, by Douglas Hofstadter. Spinonym, neun (German for nine) 9.

Spinonym, neun (German for nine) 9..gif) Rotational ambigram, "Two in One", 180° rotational symmetry.

Rotational ambigram, "Two in One", 180° rotational symmetry. Mirror ambigrams reading Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Violet, Doug (for Douglas Hofstadter, signature).

Mirror ambigrams reading Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Violet, Doug (for Douglas Hofstadter, signature). Mirror and rotational ambigram of an arithmetic operation illustrating the commutative property, 2+1+5=8.

Mirror and rotational ambigram of an arithmetic operation illustrating the commutative property, 2+1+5=8. Mirror ambigram "Love Song" in a book.

Mirror ambigram "Love Song" in a book..gif) Ambigram "Stay Here", 180° rotational symmetry.

Ambigram "Stay Here", 180° rotational symmetry.

Ambigram "Wikipedia", 180° rotational symmetry.

Ambigram "Wikipedia", 180° rotational symmetry. Ambigram ABBA.

Ambigram ABBA. Ambigram "Bounce", 180° rotational symmetry. Word printed inside an Adidas pink shoe.

Ambigram "Bounce", 180° rotational symmetry. Word printed inside an Adidas pink shoe. Ambigram "Zen Yes" in white letters with yellow meditation pictogram, embroidered on a blue T-shirt. Mirror symmetry (vertical axis).

Ambigram "Zen Yes" in white letters with yellow meditation pictogram, embroidered on a blue T-shirt. Mirror symmetry (vertical axis)..jpg.webp) Ambigram "Cognac / Danger", mirror symmetry (vertical axis), front and back, on a set of two shot glasses. Humorous warning related to alcohol consumption.

Ambigram "Cognac / Danger", mirror symmetry (vertical axis), front and back, on a set of two shot glasses. Humorous warning related to alcohol consumption.

_-_animated.gif) Ambigram "incredible!". 180° rotational symmetry.

Ambigram "incredible!". 180° rotational symmetry.

.gif) Ambigram "Travel", 180° rotational symmetry.

Ambigram "Travel", 180° rotational symmetry..gif) Ambigram "Real world / Prank Fake", 180° rotational symmetry.

Ambigram "Real world / Prank Fake", 180° rotational symmetry._-_animated.gif)

.gif) Ambigram "Wrong! / Ignore", 90° rotational symmetry.

Ambigram "Wrong! / Ignore", 90° rotational symmetry..gif)

Sun Microsystems ambigram logo, 90° and 180° rotational symmetries, designed by professor Vaughan Pratt in 1982.

Sun Microsystems ambigram logo, 90° and 180° rotational symmetries, designed by professor Vaughan Pratt in 1982.

See also

References

- Polster, Burkard. "Mathemagical Ambigrams" (PDF). Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- R. Langford-James, A Dictionary of the Eastern Orthodox Church, Ayer Publishing, ISBN 0-8337-5047-X, p. 61.

- Barry J. Blake, Secret Language: Codes, Tricks, Spies, Thieves, and Symbols, Oxford University Press, 2010, ISBN 0-19-957928-8, p. 15.

- Verbeek, Gustave (2009). The Upside-Down World of Gustave Verbeek. Sunday Press. ISBN 978-0976888574.

- c:File:Ambigrams by Gustave Verbeek (1904) - comics The Upside Downs of Little Lady Lovekins and Old Man Muffaroo - The wonderful cure of the waterfall.jpg

- c:File:Ambigrams by Gustave Verbeek (1904) - comics The Upside Downs of Little Lady Lovekins and Old Man Muffaroo - The wonderful cure of the waterfall (panel 4).jpg

- c:File:Ambigrams by Gustave Verbeek (1904) - comics The Upside Downs of Little Lady Lovekins and Old Man Muffaroo - At the house of the writing pig (panel 4).jpg

- c:File:Ambigrams by Gustave Verbeek (1904) - comics The Upside Downs of Little Lady Lovekins and Old Man Muffaroo - At the house of the writing pig (panel 5).jpg

- c:File:Ambigrams by Gustave Verbeek (1904) - comics The Upside Downs of Little Lady Lovekins and Old Man Muffaroo - The bad snake and the good wizard.jpg

- c:File:Ambigrams by Gustave Verbeek (1904) - comics The Upside Downs of Little Lady Lovekins and Old Man Muffaroo - The bad snake and the good wizard (panel 5).jpg

- Ivarsson, Marcus (2012). Uppåner med lilla Lisen & gamle Muppen. Epix. ISBN 9789170895241.

- Newnes, George (1908). "Curiosities". The Strand Magazine. No. 36. p. 359. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- "Raymond Loewy Biographie". Raymond-loewy.un-jour.org (in French). Archived from the original on 8 June 2009. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Pierce, Scott (20 May 2009). "Typography Two Ways: Calligraphy With a Twist". Wired. Wired.com. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- "New Man" (in French). Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- "1975 Prototype Logo". Car and Driver. July 1977. Retrieved 6 November 2016. In 1977, only the single 1975 prototype existed. Note that there are multiple visible differences between the prototype vehicle and later production models, including the design of the front end.

- "Motor City eyebrows were raised when DeLorean married model Cristina Ferrare". US Magazine. 1 November 1977. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Bearn, Emily (4 December 2005). "The Doodle Bug". The Telegraph. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Langdon, John. "Starship". johnlangdon.net. John Langdon. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- "Angel Logo". angelrocks.com. 2 October 2009. Archived from the original on 7 November 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Brown, Dan (21 December 2005). "As a tribute to John Langdon, I named the protagonist Robert Langdon". Popularculture.it (in Italian). Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- "The Princess Bride (20th Anniversary Widescreen Edition) (Bilingual)". amazon.ca. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Hoffman, Jenn (9 May 2015). "This Charger that Says 'Jews' Is Today's Tech Fail". motherboard.com. Vice. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- "Types of Ambigrams | John Langdon". John Langdon. Retrieved 2018-10-17.

- Kim, Scott (1981). "Tree". scottkim.com. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- See Hofstadter, Ambigrammi, p. 48.

- Prokhorov, Nikita (2013). Ambigrams Revealed: A Graphic Designer's Guide To Creating Typographic Art Using Optical Illusions, Symmetry, and Visual Perception. New Riders. pp. 51, 124. ISBN 9780133086461.

- Langdon, John (2005). WordPlay. Bantam Press. ISBN 0-593-05569-1.

- Polster, Burkard (2007). Eye Twisters. Constable. ISBN 978-1-84529-629-2.

- Borgmann, Dmitri (1965). Language on Vacation: An Olio of Orthographical Oddities. Scribner. p. 27. ASIN B0007FH4IE.

- OMNI magazine, September 1979, page 143, work of Scott Kim.

- Kim, Scott (1980). Inversions: Catalogue of Calligraphic Cartwheels. McGraw-Hill Inc., US. ISBN 0-07-034546-5.

Further reading

- Borgmann, Dmitri A., Language on Vacation: An Olio of Orthographical Oddities, Charles Scribner's Sons (1965)

- Kim, Scott, Inversions: A Catalog of Calligraphic Cartwheels, Byte Books (1981, republished 1996)

- Hofstadter, Douglas R., "Metafont, Metamathematics, and Metaphysics: Comments on Donald Knuth's Article 'The Concept of a Meta-Font'" Scientific American (August 1982) (republished, with a postscript, as chapter 13 in the book Metamagical Themas)

- Langdon, John, Wordplay: Ambigrams and Reflections on the Art of Ambigrams, Harcourt Brace (1992, republished 2005)

- Hofstadter, Douglas R., Ambigrammi: Un microcosmo ideale per lo studio della creativita (Ambigrams: An Ideal Microworld for the Study of Creativity), Hopefulmonster Editore Firenze (1987) (in Italian)

- Polster, Burkard, Les Ambigrammes l'art de symétriser les mots, Editions Ecritextes (2003) (in French)

- Polster, Burkard, Eye Twisters: Ambigrams, Escher, and Illusions (2007)

- Polster, Burkard, Eye Twisters: Ambigrams & Other Visual Puzzles to Amaze and Entertain, Constable (2007)

- Prokhorov, Nikita, Ambigrams Revealed: A Graphic Designer's Guide To Creating Typographic Art Using Optical Illusions, Symmetry, and Visual Perception New Riders (2013)