Palindrome

A palindrome is a word, number, phrase, or other sequence of characters which reads the same backward as forward, such as madam or racecar. There are also numeric palindromes, including date/time stamps using short digits 11/11/11 11:11 and long digits 02/02/2020. Sentence-length palindromes ignore capitalization, punctuation, and word boundaries.

.jpg.webp)

Composing literature in palindromes is an example of constrained writing.

The word palindrome was introduced by Henry Peacham in 1638.[1] It is derived from the Greek roots πάλιν 'again' and δρóμος 'way, direction'; a different word is used in Greek, καρκινικός 'carcinic' (lit. crab-like) to refer to letter-by-letter reversible writing.[2][3]

History

The ancient Greek poet Sotades (3rd century BCE) invented a form of Ionic meter called Sotadic or Sotadean verse, which is sometimes said to have been palindromic,[4] but no examples survive,[5] and the exact nature of the "reverse" readings is unclear.[6][7][8]

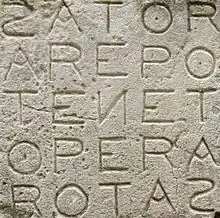

A palindrome was found as a graffito at Herculaneum, a city buried by ash in 79 CE. This palindrome, called the Sator Square, consists of a sentence written in Latin: "Sator Arepo Tenet Opera Rotas" ("The sower Arepo holds with effort the wheels"). It is remarkable for the fact that the first letters of each word form the first word, the second letters form the second word, and so forth. Hence, it can be arranged into a word square that reads in four different ways: horizontally or vertically from either top left to bottom right or bottom right to top left. As such, they can be referred to as palindromatic.

A palindrome with the same square property is the Hebrew palindrome, "We explained the glutton who is in the honey was burned and incinerated", (פרשנו רעבתן שבדבש נתבער ונשרף; perashnu: ra`avtan shebad'vash nitba`er venisraf), credited to Abraham ibn Ezra in 1924,[9] and referring to the halachic question as to whether a fly landing in honey makes the honey treif (non-kosher).

The palindromic Latin riddle "In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni" ("we go in a circle at night and are consumed by fire") describes the behavior of moths. It is likely that this palindrome is from medieval rather than ancient times. The second word, borrowed from Greek, should properly be spelled gyrum.

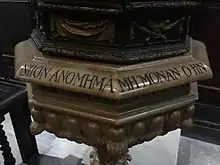

Byzantine Greeks often inscribed the palindrome, "Wash [thy] sins, not only [thy] face" ΝΙΨΟΝ ΑΝΟΜΗΜΑΤΑ ΜΗ ΜΟΝΑΝ ΟΨΙΝ ("Nip͜s on anomēmata mē monan op͜s in"), attributed to Gregory of Nazianzus,[5] on baptismal fonts; most notably in the basilica of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. A variant, also a palindrome, replaces the plural ΑΝΟΜΗΜΑΤΑ ("sins") by the singular ΑΝΟΜΗΜΑ ("sin"). This practice was continued in many churches in Western Europe, such as the font at St. Mary's Church, Nottingham and also the font of St. Stephen d'Egres, Paris; at St. Menin's Abbey, Orléans; at Dulwich College; and at the following churches in England: Worlingworth (Suffolk), Harlow (Essex), Knapton (Norfolk), St Martin, Ludgate (London), and Hadleigh (Suffolk).

A Greek poet in 1802 Vienna even composed a poem, Ποίημα Καρκινικόν (Carcinic Poem), in Ancient Greek, where every one of the 455 lines was a palindrome.[10][11]

In English, there are dozens of palindrome words, such as eye, madam, and deified, but English writers generally only cited Latin and Greek palindromic sentences in the early 19th century,[12] even though John Taylor had coined one in 1614: "Lewd did I live, & evil I did dwel" (with the ampersand being something of a "fudge"[13]). This is generally considered to be the first English-language palindrome sentence, and was long reputed (notably by James "Hermes" Harris) to be the only one, despite many efforts to find others.[10][14] (Taylor had also composed two other, "rather indifferent", palindromic lines of poetry: "Deer Madam, Reed", "Deem if I meed".[4]) Then in 1848, a certain "J.T.R." coined "Able was I ere I saw Elba", which became famous after it was (implausibly) attributed to Napoleon.[15][14]

In recent history, there have been competitions related to palindromes, such as the 2012 World Palindrome Championship, set in Brooklyn, USA.[16]

Famous palindromes

Some well-known English palindromes are, "Able was I ere I saw Elba" (1848),[17] "A man, a plan, a canal – Panama" (1948),[18] "Madam, I'm Adam" (1861),[19] and "Never odd or even".

English palindromes of notable length include mathematician Peter Hilton's "Doc, note: I dissent. A fast never prevents a fatness. I diet on cod"[20] and Scottish poet Alastair Reid's "T. Eliot, top bard, notes putrid tang emanating, is sad; I'd assign it a name: gnat dirt upset on drab pot toilet."[21]

Types

Characters, words, or lines

The most familiar palindromes in English are character-unit palindromes. The characters read the same backward as forward. Some examples of palindromic words are redivider, deified, civic, radar, level, rotor, kayak, reviver, racecar, madam, and refer.

There are also word-unit palindromes in which the unit of reversal is the word ("Is it crazy how saying sentences backwards creates backwards sentences saying how crazy it is?"). Word-unit palindromes were made popular in the recreational linguistics community by J. A. Lindon in the 1960s. Occasional examples in English were created in the 19th century. Several in French and Latin date to the Middle Ages.[22]

There are also line-unit palindromes, most often poems. These possess an initial set of lines which, precisely halfway through, is repeated in reverse order, without alteration to word order within each line, and in a way that the second half continues the "story" related in the first half in a way that makes sense, this last being key.[23]

Sentences and phrases

Palindromes often consist of a sentence or phrase, e.g., "Mr. Owl ate my metal worm", "Do geese see God?", "Was it a car or a cat I saw?", "Murder for a jar of red rum" or "Go hang a salami, I'm a lasagna hog". Punctuation, capitalization, and spaces are usually ignored. Some, such as "Rats live on no evil star", "Live on time, emit no evil", and "Step on no pets", include the spaces.

Semordnilap

Semordnilap (palindromes spelled backward) is a name coined for words that spell a different word in reverse. The word was coined by Martin Gardner in his notes to C.C. Bombaugh's book Oddities and Curiosities of Words and Literature in 1961.[24]

An example of this is the word stressed, which is desserts spelled backward.

Some semordnilaps are deliberate creations. An example in electronics (although rarely used now) is the mho, a unit of electrical conductance, which is ohm spelled backwards, the unit of electrical resistance and the reciprocal of conductance. Similarly, the daraf, a unit of elastance, is farad spelled backwards, the unit of capacitance and the reciprocal of elastance. In fiction, many characters have names deliberately made to be semordnilaps of other names or words, such as Alucard (a semordnilap of "Dracula").

Semordnilaps are also known as emordnilaps,[25] word reversals, reversible anagrams,[26] heteropalindromes, semi-palindromes, half-palindromes, reversgrams, mynoretehs, volvograms, anadromes,[27][28][29] and levidromes.[30][31] They have also sometimes been called antigrams,[27] though this term usually refers to anagrams which have opposite meanings. As of October 2018, none of these terms have been accepted as official entries in the Oxford English Dictionary.[32]

Names

Some names are palindromes, such as the given names Hannah, Ava, Anna, Eve, Bob and Otto, or the surnames Harrah, Renner, Salas, and Nenonen. Lon Nol (1913–1985) was Prime Minister of Cambodia. Nisio Isin is a Japanese novelist and manga writer, whose pseudonym (西尾 維新, Nishio Ishin) is a palindrome when romanized using the Kunrei-shiki or the Nihon-shiki systems, and is often written as NisiOisiN to emphasize this. Some people have changed their name in order to make it palindromic (such as actor Robert Trebor and rock-vocalist Ola Salo), while others were given a palindromic name at birth (such as the philologist Revilo P. Oliver, the flamenco dancer Sara Baras, the sportswriter Mark Kram and the creator of the Eden Project Tim Smit).

There are also palindromic names in fictional media. "Stanley Yelnats" is the name of the main character in Holes, a 1998 novel and 2003 film. Four of the fictional Pokémon species have palindromic names in English (Eevee, Girafarig, Ho-Oh, and Alomomola).

The 1970s pop band ABBA is a palindrome using the starting letter of the first name of each of the four band members.

Numbers

The digits of a palindromic number are the same read backwards as forwards, for example, 91019; decimal representation is usually assumed. In recreational mathematics, palindromic numbers with special properties are sought. For example, 191 and 313 are palindromic primes.

Whether Lychrel numbers exist is an unsolved problem in mathematics about whether all numbers become palindromes when they are continuously reversed and added. For example, 56 is not a Lychrel number as 56 + 65 = 121, and 121 is a palindrome. The number 59 becomes a palindrome after three iterations: 59 + 95 = 154; 154 + 451 = 605; 605 + 506 = 1111, so 59 is not a Lychrel number either. Numbers such as 196 are thought to never become palindromes when this reversal process is carried out and are therefore suspected of being Lychrel numbers. If a number is not a Lychrel number, it is called a "delayed palindrome" (56 has a delay of 1 and 59 has a delay of 3). In January 2017 the number 1,999,291,987,030,606,810 was published in OEIS as A281509, and described as "The Largest Known Most Delayed Palindrome", with a delay of 261. Several smaller 261-delay palindromes were published separately as A281508.

Every positive integer can be written as the sum of three palindromic numbers in every number system with base 5 or greater.[33]

The continued fraction of √n + ⌊√n⌋ is a repeating palindrome when n is an integer, where ⌊x⌋ denotes the integer part of x.

Dates

A day or timestamp is a palindrome when its digits are the same when reversed. Only the digits are considered in this determination and the component separators (hyphens, slashes, and dots) are ignored. Short digits may be used as in 11/11/11 11:11 or long digits as in 2 February 2020.

A notable palindrome day is this century's 2 February 2020 because this date is a palindrome regardless of the date format by country (yyyy-mm-dd, dd-mm-yyyy, or mm-dd-yyyy) used in various countries. For this reason, this date has also been termed as a "Universal Palindrome Day".[34][35] Other universal palindrome days include, almost a millennium previously, 11/11/1111, the future 12/12/2121, and in a millennium 03/03/3030.[36]

In speech

A phonetic palindrome is a portion of speech that is identical or roughly identical when reversed. It can arise in context where language is played with, for example in slang dialects like verlan.[37] In the French language, there is the phrase une Slave valse nue ("a Slavic woman waltzes naked"), phonemically /yn slav vals ny/.[38] John Oswald discussed his experience of phonetic palindromes while working on audio tape versions of the cut-up technique using recorded readings by William S. Burroughs.[39][40] A list of phonetic palindromes discussed by word puzzle columnist O.V. Michaelsen (Ove Ofteness) include "crew work"/"work crew", "dry yard", "easy", "Funny enough", "Let Bob tell", "new moon", "selfless", "Sorry, Ross", "Talk, Scott", "to boot", "top spot" (also an orthographic palindrome), "Y'all lie", "You're caught. Talk, Roy", and "You're damn mad, Roy".[41]

Classical music

Joseph Haydn's Symphony No. 47 in G is nicknamed "the Palindrome". In the third movement, a minuet and trio, the second half of the minuet is the same as the first but backwards, the second half of the ensuing trio similarly reflects the first half, and then the minuet is repeated.

The interlude from Alban Berg's opera Lulu is a palindrome, as are sections and pieces, in arch form, by many other composers, including James Tenney, and most famously Béla Bartók. George Crumb also used musical palindrome to text paint the Federico García Lorca poem "¿Por qué nací?", the first movement of three in his fourth book of Madrigals. Igor Stravinsky's final composition, The Owl and the Pussy Cat, is a palindrome.[42]

The first movement from Constant Lambert's ballet Horoscope (1938) is entitled "Palindromic Prelude". Lambert claimed that the theme was dictated to him by the ghost of Bernard van Dieren, who had died in 1936.[43]

British composer Robert Simpson also composed music in the palindrome or based on palindromic themes; the slow movement of his Symphony No. 2 is a palindrome, as is the slow movement of his String Quartet No. 1. His hour-long String Quartet No. 9 consists of thirty-two variations and a fugue on a palindromic theme of Haydn (from the minuet of his Symphony No. 47). All of Simpson's thirty-two variations are themselves palindromic.

Hin und Zurück ("There and Back": 1927) is an operatic 'sketch' (Op. 45a) in one scene by Paul Hindemith, with a German libretto by Marcellus Schiffer. It is essentially a dramatic palindrome. Through the first half, a tragedy unfolds between two lovers, involving jealousy, murder and suicide. Then, in the reversing second half, this is replayed with the lines sung in reverse order to produce a happy ending.

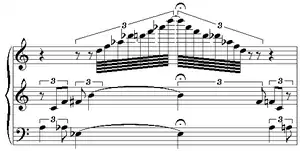

The music of Anton Webern is often palindromic. Webern, who had studied the music of the Renaissance composer Heinrich Isaac, was extremely interested in symmetries in music, be they horizontal or vertical. An example of horizontal or linear symmetry in Webern's music is the first phrase in the second movement of the symphony, Op. 21. A striking example of vertical symmetry is the second movement of the Piano Variations, Op. 27, in which Webern arranges every pitch of this dodecaphonic work around the central pitch axis of A4. From this, each downward reaching interval is replicated exactly in the opposite direction. For example, a G♯3—13 half-steps down from A4 is replicated as a B♭5—13 half-steps above.

Just as the letters of a verbal palindrome are not reversed, so are the elements of a musical palindrome usually presented in the same form in both halves. Although these elements are usually single notes, palindromes may be made using more complex elements. For example, Karlheinz Stockhausen's composition Mixtur, originally written in 1964, consists of twenty sections, called "moments", which may be permuted in several different ways, including retrograde presentation, and two versions may be made in a single program. When the composer revised the work in 2003, he prescribed such a palindromic performance, with the twenty moments first played in a "forwards" version, and then "backwards". Each moment, however, is a complex musical unit, and is played in the same direction in each half of the program.[44] By contrast, Karel Goeyvaerts's 1953 electronic composition, Nummer 5 (met zuivere tonen) is an exact palindrome: not only does each event in the second half of the piece occur according to an axis of symmetry at the centre of the work, but each event itself is reversed, so that the note attacks in the first half become note decays in the second, and vice versa. It is a perfect example of Goeyvaerts's aesthetics, the perfect example of the imperfection of perfection.[45]

In classical music, a crab canon is a canon in which one line of the melody is reversed in time and pitch from the other. A large-scale musical palindrome covering more than one movement is called "chiastic", referring to the cross-shaped Greek letter "χ" (pronounced /ˈkaɪ/.) This is usually a form of reference to the crucifixion; for example, the Crucifixus movement of Bach's Mass in B minor. The purpose of such palindromic balancing is to focus the listener on the central movement, much as one would focus on the centre of the cross in the crucifixion. Other examples are found in Bach's cantata BWV 4, Christ lag in Todes Banden, Handel's Messiah and Fauré's Requiem.[46]

A table canon is a rectangular piece of sheet music intended to be played by two musicians facing each other across a table with the music between them, with one musician viewing the music upside down compared to the other. The result is somewhat like two speakers simultaneously reading the Sator Square from opposite sides, except that it is typically in two-part polyphony rather than in unison.

Long palindromes

The longest palindromic word in the Oxford English Dictionary is the onomatopoeic tattarrattat, coined by James Joyce in Ulysses (1922) for a knock on the door.[47][48] The Guinness Book of Records gives the title to detartrated, the preterite and past participle of detartrate, a chemical term meaning to remove tartrates. Rotavator, a trademarked name for an agricultural machine, is often listed in dictionaries. The term redivider is used by some writers, but appears to be an invented or derived term—only redivide and redivision appear in the Shorter Oxford Dictionary. Malayalam, a language of southern India, is of equal length.

In English, two palindromic novels have been published: Satire: Veritas by David Stephens (1980, 58,795 letters), and Dr Awkward & Olson in Oslo by Lawrence Levine (1986, 31,954 words).[49] Another palindromic English work is a 224-word long poem, "Dammit I'm Mad", written by Demetri Martin.[50]

According to Guinness World Records, the Finnish 19-letter word saippuakivikauppias (a soapstone vendor), is the world's longest palindromic word in everyday use.[51]

Biological structures

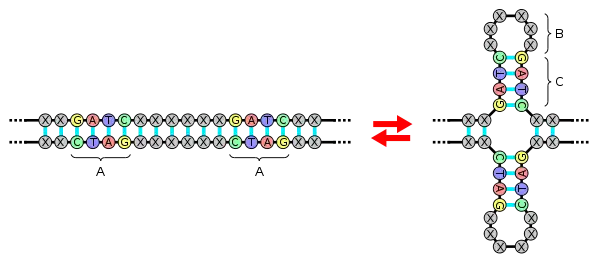

A: Palindrome, B: Loop, C: Stem

In most genomes or sets of genetic instructions, palindromic motifs are found. The meaning of palindrome in the context of genetics is slightly different, however, from the definition used for words and sentences. Since the DNA is formed by two paired strands of nucleotides, and the nucleotides always pair in the same way (Adenine (A) with Thymine (T), Cytosine (C) with Guanine (G)), a (single-stranded) sequence of DNA is said to be a palindrome if it is equal to its complementary sequence read backward. For example, the sequence ACCTAGGT is palindromic because its complement is TGGATCCA, which is equal to the original sequence in reverse complement.

A palindromic DNA sequence may form a hairpin. Palindromic motifs are made by the order of the nucleotides that specify the complex chemicals (proteins) that, as a result of those genetic instructions, the cell is to produce. They have been specially researched in bacterial chromosomes and in the so-called Bacterial Interspersed Mosaic Elements (BIMEs) scattered over them. Recently a research genome sequencing project discovered that many of the bases on the Y-chromosome are arranged as palindromes.[52] A palindrome structure allows the Y-chromosome to repair itself by bending over at the middle if one side is damaged.

It is believed that palindromes frequently are also found in proteins,[53][54] but their role in the protein function is not clearly known. It has recently[55] been suggested that the prevalence existence of palindromes in peptides might be related to the prevalence of low-complexity regions in proteins, as palindromes frequently are associated with low-complexity sequences. Their prevalence might also be related to an alpha helical formation propensity of these sequences,[55] or in formation of proteins/protein complexes.[56]

Computation theory

In automata theory, a set of all palindromes in a given alphabet is a typical example of a language that is context-free, but not regular. This means that it is impossible for a computer with a finite amount of memory to reliably test for palindromes. (For practical purposes with modern computers, this limitation would apply only to impractically long letter-sequences.)

In addition, the set of palindromes may not be reliably tested by a deterministic pushdown automaton which also means that they are not LR(k)-parsable or LL(k)-parsable. When reading a palindrome from left-to-right, it is, in essence, impossible to locate the "middle" until the entire word has been read completely.

It is possible to find the longest palindromic substring of a given input string in linear time.[57][58]

The palindromic density of an infinite word w over an alphabet A is defined to be zero if only finitely many prefixes are palindromes; otherwise, letting the palindromic prefixes be of lengths nk for k=1,2,... we define the density to be

Among aperiodic words, the largest possible palindromic density is achieved by the Fibonacci word, which has density 1/φ, where φ is the Golden ratio.[59]

A palstar is a concatenation of palindromic strings, excluding the trivial one-letter palindromes – otherwise all strings would be palstars.[57]

Notable palindromists

See also

- Ambigram

- Anagram

- Ananym

- Anastrophe, different word order

- Antimetabole

- Backmasking

- "Bob" by "Weird Al" Yankovic

- Constrained writing

- Eodermdrome

- I Palindrome I by They Might Be Giants

- List of palindromic places

- Longest palindromic substring

- Mirror writing

- Palindroma, a genus of spiders with palindromic species names

- Palindromic number

- Palindromic polynomial

- Pangram

- Phonetic palindrome

- Yreka, California for the palindromic Yreka Bakery and Yrella Gallery

References

- Henry Peacham, The Truth of our Times Revealed out of One Mans Experience, 1638, p. 123

- Triantaphylides Dictionary, Portal for the Greek Language. "Combined word search for καρκινικός". www.greek-language.gr. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- William Martin Leake, Researches in Greece, 1814, p. 85

- H.B. Wheatley, Of Anagrams: A Monograph Treating of Their History from the Earliest Ages..., London, 1862, p. 9-11

- Alex Preminger, ed., Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, 1965, JSTOR j.ctt13x0qvn, s.v. 'palindrome', p. 596

- Jan Kwapisz, The Paradign of Simias: Essays on Poetic Eccentricity, p. 62-68

- Alex Preminger, ed., Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, 1965, JSTOR j.ctt13x0qvn, s.v. 'Sotadean', p. 784

- The Century Dictionary, 1889, s.v. 'Sotadic', p. 5:5780. "Sotadic verse... A palindromic verse; so named apparently from some ancient examples of Sotadean verse being palindromic."

- Soclof, Adam (28 December 2011). "Jewish Wordplay". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- "On Palindromes" The New Monthly Magazine 2:170-173 (July–December 1821)

- Αμβρόσιος Ιερομόναχος του Παμπέρεως (Hieromonk Ambrosios Pamperis), Ποίημα Καρκινικόν, Vienna, 1802 full text

- S(ilvanus) Urban, "Classical Literature: On Macaronic Poetry", The Gentleman's Magazine, or Monthly Intelligencer, London, 100:part 2:34-36 (New Series 23) (July 1830)

- Richard Lederer, The Word Circus: A Letter-perfect Book, 1998, ISBN 0877793549, p.54

- "Ingenious Arrangement of Words", The Gazette of the Union, Golden Rule, and Odd Fellows' Family Companion 9:30 (July 8, 1848)

- "Able Was I Ere I Saw Elba", Quote Investigator September 15, 2013

- Steinmetz, Katy (4 April 2015). ""Madam, I'm Adam": Meet the World Palindrome Champion". Time. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Alluding to the first exile of Napoleon to Elba

- By Leigh Mercer, published in Notes and Queries, 13 November 1948, according to The Yale Book of Quotations, F. R. Shapiro, ed. (2006, ISBN 0-300-10798-6).

- Do you give it up?: A collection of the most amusing conundrums, riddles, etc. of the day, London, 1861, p. 4

- "Professor Peter Hilton". Daily Telegraph. London. 10 November 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- By Brendan Gill, published in Here At The New Yorker, (1997, ISBN 0-306-80810-2).

- Mark J. Nelson (7 February 2012). "Word-unit palindromes". Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- "Never Odd Or Even, and Other Tricks Words Can Do" by O.V. Michaelsen (Sterling Publishing Company: New York), 2005 p124-7

- Bombaugh, C.C. (1961). Martin Gardner (ed.). Oddities and Curiosities of Words and Literature (first ed.). Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. p. 345.

- "Reverse Pairs (Emordnilap Words)". sightwordsgame.com.

- "AskOxford: What is the word for a word that is another word spelt backwards?". Oxforddictionaries.com. Archived from the original on 2 December 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- "Anagrams FAQ Page – Are there any unusual varieties of anagram?". Anagrammy.com. 19 March 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- Sprachwissenschaft (in German). C. Winter Universitätsverlag. 1984. p. 245. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- Astle, D. (2012). Puzzled: Secrets and clues from a life in words. Profile. p. 248. ISBN 978-1-84765-816-6. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- Harnett, Cindy E. "Victoria boy's new word, 'levidrome,' on its way to Oxford Dictionary". Times Colonist.

- "'Levidrome' may be Oxford Dictionary's next word thanks to B.C. boy's viral campaign". Global News.

- https://www.timescolonist.com/news/local/latest-word-on-levidrome-oxford-says-it-s-not-ready-but-linguist-begs-to-differ-1.23462827

- Cilleruelo, Javier; Luca, Florian; Baxter, Lewis (19 February 2016). "Every positive integer is a sum of three palindromes". arXiv:1602.06208 [math.NT].

- "Universal Palindrome Day". 2 February 2020.

- "#PalindromeDay: Geeks around the world celebrate 02/02/2020". BBC. 2 February 2020.

- Held, Amy (2 February 2020). "Why A Day Like Sunday Hasn't Been Seen In 900 Years". NPR.

- Goertz, Karein K. (2003). "Showing Her Colors: An Afro-German Writes the Blues in Black and White". Callaloo. 26 (2): 306–319. doi:10.1353/cal.2003.0045. JSTOR 3300855. S2CID 161346520.

- Durand, Gerard (2003). Palindromes en Folie. Les Dossiers de l'Aquitaine. p. 32. ISBN 978-2846220361.

- "Section titled "On Burroughs and Burrows ..."". Pfony.com. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- Reversible audio cut-ups of William S. Burroughs' voice, including an acoustic palindrome in example 5 (requires Flash)

- Michaelsen, O.V. (1998). Words at play: quips, quirks and oddities. Sterling.

- A helpful list is at http://deconstructing-jim.blogspot.com/2010/03/musical-palindromes.html

- "Answers.com". Answers.com. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- Rudolf Frisius, Karlheinz Stockhausen II: Die Werke 1950–1977; Gespräch mit Karlheinz Stockhausen, "Es geht aufwärts" (Mainz, London, Berlin, Madrid, New York, Paris, Prague, Tokyo, Toronto: Schott Musik International, 2008): 164–65. ISBN 978-3-7957-0249-6.

- M[orag] J[osephine] Grant, Serial Music, Serial Aesthetics: Compositional Theory in Post-war Europe (Cambridge, U.K.; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001): 64–65.

- Charton, Shawn E. Jennens vs. Handel: Decoding the Mysteries of Messiah.

- James Joyce (1982). Ulysses. Editions Artisan Devereaux. pp. 434–. ISBN 978-1-936694-38-9.

...I was just beginning to yawn with nerves thinking he was trying to make a fool of me when I knew his tattarrattat at the door he must ...

- O.A. Booty (1 January 2002). Funny Side of English. Pustak Mahal. pp. 203–. ISBN 978-81-223-0799-3.

The longest palindromic word in English has 12 letters: tattarrattat. This word, appearing in the Oxford English Dictionary, was invented by James Joyce and used in his book Ulysses (1922), and is an imitation of the sound of someone ...

- Eckler, Ross (1996). Making the Alphabet Dance. NY: St. Martin's. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-333-90334-6.

- "Demetri Martin's Palindrome". Yale University. Mathematics Department. Archived from the original on 29 June 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- "Longest palindromic word". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- "2003 Release: Mechanism Preserves Y Chromosome Gene". National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI). Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- Ohno S (1990). "Intrinsic evolution of proteins. The role of peptidic palindromes". Riv. Biol. 83 (2–3): 287–91, 405–10. PMID 2128128.

- Giel-Pietraszuk M, Hoffmann M, Dolecka S, Rychlewski J, Barciszewski J (February 2003). "Palindromes in proteins" (PDF). J. Protein Chem. 22 (2): 109–13. doi:10.1023/A:1023454111924. PMID 12760415. S2CID 28294669.

- Sheari A, Kargar M, Katanforoush A, et al. (2008). "A tale of two symmetrical tails: structural and functional characteristics of palindromes in proteins". BMC Bioinformatics. 9: 274. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-9-274. PMC 2474621. PMID 18547401.

- Pinotsis N, Wilmanns M (October 2008). "Protein assemblies with palindromic structure motifs". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65 (19): 2953–6. doi:10.1007/s00018-008-8265-1. PMID 18791850. S2CID 29569626.

- Crochemore, Maxime; Rytter, Wojciech (2003), "8.1 Searching for symmetric words", Jewels of Stringology: Text Algorithms, World Scientific, pp. 111–114, ISBN 978-981-02-4897-0

- Gusfield, Dan (1997), "9.2 Finding all maximal palindromes in linear time", Algorithms on Strings, Trees, and Sequences, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 197–199, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511574931, ISBN 978-0-521-58519-4, MR 1460730

- Adamczewski, Boris; Bugeaud, Yann (2010), "8. Transcendence and diophantine approximation", in Berthé, Valérie; Rigo, Michael (eds.), Combinatorics, automata, and number theory, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications, 135, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 443, ISBN 978-0-521-51597-9, Zbl 1271.11073

Further reading

- Word Ways: The Journal of Recreational Linguistics. Greenwood Periodicals et al., 1968–. ISSN 0043-7980.

- The Palindromist. Palindromist Press, 1996–.

- Howard W. Bergerson. Palindromes and Anagrams. Dover Publications, 1973. ISBN 978-0486206646.

- Dmitri A.Borgman. Language on Vacation. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1965. ISBN 978-0006523086

- Stephen J. Chism. From A to Zotamorf: The Dictionary of Palindromes. Word Ways Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0963515209.

- Michael Donner. I Love Me, Vol. I: S. Wordrow's Palindrome Encyclopedia. Algonquin Books, 1996. ISBN 978-1565121096.

External links

| Look up palindrome or Appendix:English palindromes in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Palindrome |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Palindromes. |

- "Palindromes". Several languages. European Day of Languages (EDL).

Celebrated Sep 26