American ghettos

Ghettos in the United States are typically urban neighborhoods perceived as being high in crime and poverty. The origins of these areas are specific to the United States and its laws, which created ghettos through both legislation and private efforts to segregate America for political, economic, social, and ideological reasons: de jure[1] and de facto segregation. De facto segregation continues today in ways such as residential segregation and school segregation because of contemporary behavior and the historical legacy of de jure segregation.

American ghettos therefore, are communities and neighborhoods where government has not only concentrated a minority group, but established barriers to its exit.[1] “Inner city” is often used to avoid the word ghetto, but typically denotes the same idea. Geographic examples of American ghettos are seen in large urban centers such as New York City, Chicago, and Detroit.

Description

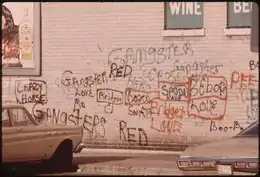

"American ghetto" usually denotes an urban neighborhood with crime, gang violence, and extreme poverty,[2][3] with a significant number of minority citizens living in it.

Their origins are manifold. Historically, violence has been used to intimidate certain demographics into remaining in ghettos.[4] The "deindustrialization" of minorities and the lower class Americans also contributed to ghetto-forming in inner cities. Additional causes of deteriorating conditions in ghettos ranged from lack of jobs and extreme poverty to menacing streets and violence.[5] Development of ghettos through modern housing segregation can also be blamed on de facto racism as well as de jure segregation. Centralized racism began the segregation, but, with the legal barriers to entry for blacks having fallen, the price rather than the legality of living in certain areas has excluded blacks.[6] Rent vouchers and other forms of remittances have been proposed as a way of desegregating America.[7]

History

In the findings of a study conducted by Brandeis University, one of the major factors of the huge racial wealth gap in America is due to the disparities in home-ownership in America.[8] It will be very difficult to pinpoint the beginning of housing discrimination in America, since most forms of discrimination in America overlapped. But an extension of Jim Crow laws was made manifest in home-ownership and American housing public policies. These discriminatory federal and state policies, in conjunction with private sector fear for economic loss, led to the systemic exclusion of minorities from loans, access to credit, and higher income. This practice is called redlining.

Redlining

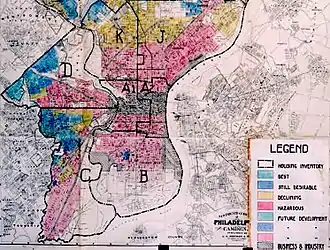

In 1933 the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC), a federal government sponsored program was created as part of President Roosevelt's New Deal to combat the Great Depression and to help assist homeowners who were in default on their mortgage and in foreclosure. This assistance was mostly in forms of loans and federal aids that last for over 25 years.[9] President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the National Housing Act of 1934 (NHA) which established the Federal Housing Administration (FHA).[10][page needed][11] This federal policy heightened the worsening of minority inner-city neighborhoods caused by the withholding of mortgage capital, and made it even more difficult for neighborhoods to attract and retain families able to purchase homes.[12][page needed] The assumptions in redlining resulted in a large increase in residential racial segregation and urban decay in the United States.[13]

The HOLC under the NHA and in cooperation with the FHA and the Federal Banking Home Loan Board sent surveyors and examiners to go to these cities and speak with local banks, city officials, to determine the lending risks in different neighborhoods. Factors for determining high-risk sectors included: Geography—where is the city located? How close is the city to a park? Does it have commercial establishments? Is it close to a factory, and will pollution be a problem? How old are the apartments or houses? Are they accessible? Are there good roads, good schools, good companies, and opportunities to work? The population, the demographics, is it a majority-minority neighborhood? Are the people mostly poor and uneducated? All of these factors play into determining whether a city is a highly desirable location for the FHA loans or a High-risk or "hazardous" zone. Color-coded maps were used to distinguish different localities based on the findings from these surveys. Green represented the best possible location to give loans. Blue represented a highly desirable locale. Yellow acknowledged a declining and depreciating area. Red identified a “Hazardous” zone. This is what was called the "Residential Security" map. Areas that were coded as red zones had to pay higher interest rates and struggled to access FHA loans.[14]

| CITY | HAZARDOUS |

|---|---|

| Macon, GA | 64.99% |

| Augusta, GA | 58.70% |

| Flint, MI | 54.19% |

| Springfield, MO | 60.19% |

| Montgomery, AL | 53.11% |

The majority of the people who lived in the red zones were blacks and other minorities. Poverty in the black community increased significantly due to a lack of jobs and assistance from the government. Access to credit was based on collateral and geographic residence of applicants which automatically disqualified most blacks and most minorities since they were concentrated in deteriorated areas. Many lower middle class and middle class blacks sought to migrate to the industrial Midwest and Northeast and other places for better opportunities and to leave the red zoned areas, but explicit racial exclusion ordinances prevented blacks from finding places outside of the red zones.[16]

Even in areas where exclusion laws were not in effect, real estate professionals instilled fear that blacks would invade white communities and eventually turn it into a red zone.[1] This led to the "white flight" – the exodus of whites out of the inner city into the suburbs – and blockbusting in the 1960s and 70s. Minorities continued to migrate into the red zoned communities, as it was difficult for them to afford to live elsewhere.[17] The higher taxes and pricing on homes and rentals in the red zones led to constant depreciation in these neighborhoods.

In addition to encouraging white families to move to suburbs by providing them loans to do so, the government uprooted many established African American communities by building elevated highways through their neighborhoods. To build a highway, tens of thousands of single-family homes were destroyed. Because these properties had been summarily declared to be "in decline," families were given pittances for their properties, and were forced into federal housing called the projects. To build these projects, still more single family homes were demolished.[18]

De facto segregation

Although Congress has passed several legislations to end de jure segregation in America, de facto segregation still persists in American schools and cities. People have the right to live in communities of their choice, and due to cultural, economic, social, and personal reasons, self-segregation continues to prevail in America.

The desire of some whites to avoid having their children attend integrated schools has been a factor in white flight to the suburbs,[19] and in the foundation of numerous segregated private schools which most African-American students, though technically permitted to attend, are unable to afford.[20] Recent studies in San Francisco showed that groups of homeowners tended to self-segregate to be with people of the same education level and race. By 1990, the legal barriers enforcing segregation had been mostly replaced by indirect factors, including the phenomenon where whites pay more than blacks to live in predominantly white areas. The residential and social segregation of whites from blacks in the United States creates a socialization process that limits whites' chances for developing meaningful relationships with blacks and other minorities. The segregation experienced by whites from blacks fosters segregated lifestyles and leads them to develop positive views about themselves and negative views about blacks.[21]

Impact of Supreme Court cases

Buchanan v. Warley

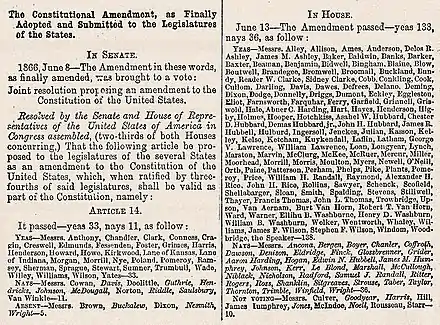

In Buchanan v. Warley, the Supreme Court of The United States sought to overturn a city ordinance that restricted housing rights. The city ordinance in question prevented blacks from buying in an area where more whites lived and whites from buying in an area where more blacks lived. As a result, year by year, the segregation of racial minorities would become more pronounced as time and restricted purchasing options funneled them into areas outside of white-dominated areas. The Supreme Court ruled by unanimous decision that the ordinance from the city of Louisville, Kentucky violated the freedom of contract guaranteed under the 14th amendment. Cities could not enact racially restrictive covenants.[22]

Corrigan v. Buckley

Corrigan v. Buckley did not directly affect the Buchanan v. Warley ruling on city ordinances, but rather it allowed neighborhoods to enact racially discriminatory covenants. The Supreme Court unanimously ruled that neighborhoods could enact racially discriminatory covenants, and that the state could enforce them. Due to the agreements being private contracts, the Court ruled that it could not be regulated by the government. As a result of this case, racially discriminatory covenants spread across the United States and led to more segregated housing.[23]

Hansberry v. Lee

In Hansberry v. Lee, the Supreme Court ruled that due to many of the affected parties not being represented in a previous case on racially exclusive covenants in a neighborhood of Chicago the case could be contested once again. This has become a landmark case for res judicata, and this opened the door to the case of Shelley v. Kraemer.[24]

Shelley v. Kraemer

Shelley v. Kraemer was a landmark case in housing rights in America. Contrary to the Supreme Court of Missouri's decision, which ruled that racial exclusionary covenants were private contracts, the Supreme Court ruled that racially exclusionary covenants violated the equal protection clause of the constitution. This decision was 6–0 due to 3 judges recusing themselves because they lived in neighborhoods with racially exclusionary covenants.[25]

See also

- African-American history

- Auto-segregation

- Black Belt (region of Chicago)

- Black flight

- Blockbusting

- Civil rights movement (1865–1896)

- Civil rights movement (1896–1954)

- Desegregation

- Housing Segregation

- Judicial aspects of race in the United States

- Laissez-Faire Racism

- List of anti-discrimination acts

- Mass racial violence in the United States

- Nadir of American race relations

- Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity

- Plessy v. Ferguson

- Race and longevity

- Racial integration

- Racial segregation

- Racism in the United States

- Second-class citizen

- Separate but equal

- St. Augustine movement

- Timeline of the civil rights movement

References

Notes

- Rothstein, Richard (2018). The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York, London: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2018. ©2017. ISBN 9781631494536. OCLC 1032305326.

- Hartmann, Douglas; Venkatesh, Sudhir Alladi (January 2002). "American Project: The Rise and Fall of a Modern Ghetto". Contemporary Sociology. 31 (1): 11. doi:10.2307/3089389. ISSN 0094-3061. JSTOR 3089389. S2CID 147680730.

- Skolnick, Jerome (Winter 1992). "Gangs in the Post-Industrial Ghetto". The American Prospect. ISSN 1049-7285. Retrieved 2019-03-11.

- Bell, Jeannine (2013). Hate thy neighbor : move-in violence and the persistence of racial segregation in American housing. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 9780814760222. OCLC 843880783.

- Thrasher, Frederic Milton (2013-03-27). The gang : a study of 1,313 gangs in Chicago. ISBN 9780226799308. OCLC 798809909.

- Cutler, David; Glaeser, Edward; Vigdor, Jacob (January 1997). "The Rise and Decline of the American Ghetto". Cambridge, MA. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.587.8018. doi:10.3386/w5881. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Fiss, Owen M. (2003). A way out : America's ghettos and the legacy of racism. Cohen, Joshua, 1951–, Decker, Jefferson., Rogers, Joel, 1952–. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400825516. OCLC 436057779.

- "Racial wealth gap continues to grow between black and white families, regardless of college attainment". heller.brandeis.edu. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- Mitchell, Bruce; Franco, Juan (2018-03-20). "HOLC "redlining" maps: The persistent structure of segregation and economic inequality". NCRC. Retrieved 2019-03-11.

- Jackson, Kenneth T. (1985), Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-504983-7

- Madrigal, Alexis C. (2014-05-22). "The Racist Housing Policy That Made Your Neighborhood". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2018-11-10.

- When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor By William Julius Wilson. 1996. ISBN 0-679-72417-6

- Rachel G Bratt; Chester Hartman; Michael E Stone, eds. (2006). A right to housing : foundation for a new social agenda. Temple University Press. ISBN 1592134327. OCLC 799498026.

- "Map of the Month: Redlining Louisville". Data-Smart City Solutions. Retrieved 2019-03-13.

- Meisenhelter, Jesse (2018-03-27). "How 1930s discrimination shaped inequality in today's cities". NCRC. Retrieved 2019-03-13.

- Hirsch, Arnold R. (1998). Making the Second Ghetto. University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226342467.001.0001. ISBN 9780226342443.

- Yarmolinsky, Adam; Liebman, Lance; Schelling, Corinne Saposs, eds. (1981). Race and schooling in the city. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674745779. OCLC 6626482.

- "When a City Turns White, What Happens to Its Black History? | History News Network". historynewsnetwork.org. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- "Segregation in the United States – MSN Encarta". 2007-04-30. Archived from the original on 2007-04-30. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- Rabby, Glenda Alice (1999). The pain and the promise : the struggle for civil rights in Tallahassee, Florida. Athens. ISBN 082032051X. OCLC 39860115.

- Cutler, David; Glaeser, Edward; Vigdor, Jacob (January 1997). "The Rise and Decline of the American Ghetto". Journal of Political Economy. 107 (3): 455–506. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.587.8018. doi:10.1086/250069. JSTOR 250069. S2CID 134413201.

- Barrera, Leticia (2013-10-28). "Performing the Court: Public Hearings and the Politics of Judicial Transparency in Argentina". PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review. 36 (2): 326–340. doi:10.1111/plar.12032. ISSN 1081-6976.

- Asch, Chris Myers (2018). Chocolate City : a history of race and democracy in the nation's capital. ISBN 9781469635873. OCLC 1038178017.

- Bourguignon, Henry J.; Allen, Cameron (1986). "A Guide to New Jersey Legal Bibliography and Legal History". Law and History Review. 4 (2): 469. doi:10.2307/743837. ISSN 0738-2480. JSTOR 743837.

- Gilmore, Brian (2013), "Shelley v. Kraemer (1948)", Multicultural America: A Multimedia Encyclopedia, SAGE Publications, Inc., doi:10.4135/9781452276274.n788, ISBN 9781452216836

Further reading

- Bishop, Kathleen. A White Face Painted Brown: the true story of a young girl's journey into the bosom of a Black and Mexican Los Angeles ghetto called Aliso Village" (1993)

- Bond, Horace Mann. "The Extent and Character of Separate Schools in the United States." Journal of Negro Education 4(July 1935):321–27. in JSTOR.

- Chafe, William Henry, Raymond Gavins, and Robert Korstad, eds. Remembering Jim Crow: African Americans Tell About Life in the Segregated South (2003).

- Graham, Hugh. The Civil Rights Era: Origins and Development of National Policy, 1960–1972 (1990)

- Guyatt, Nicholas. Bind Us Apart: How Enlightened Americans Invented Racial Segregation. New York: Basic Books, 2016.

- Hannah-Jones, Nikole. "Worlds Apart". New York Times Magazine, June 12, 2016, pp. 34–39 and 50–55.

- Hasday, Judy L. The Civil Rights Act of 1964: An End to Racial Segregation (2007).

- Lands, LeeAnn, "A City Divided", Southern Spaces, December 29, 2009.

- Levy, Alan Howard. Tackling Jim Crow: Racial Segregation in Professional Football (2003).

- Massey, Douglas S., and Nancy Denton. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass (1993)

- Merry, Michael S. (2012). "Segregation and Civic Virtue" Educational Theory Journal 62(4), pg. 465–486.

- Myrdal, Gunnar. An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (1944).

- Ritterhouse, Jennifer. Growing Up Jim Crow: The Racial Socialization of Black and White Southern Children, 1890–1940. (2006).

- Sitkoff, Harvard. The Struggle for Black Equality (2008)

- Tarasawa, Beth. "New Patterns of Segregation: Latino and African American Students in Metro Atlanta High Schools," Southern Spaces, January 19, 2009.

- Vickers, Lu; Wilson-Graham, Cynthia (2015). Remembering Paradise Park : tourism and segregation at Silver Springs. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0813061528.

- Woodward, C. Vann. The Strange Career of Jim Crow (1955).

- Yellin, Eric S. Racism in the Nation's Service: Government Workers and the Color Line in Woodrow Wilson's America. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

External links

- Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity

- File a housing discrimination complaint

- "Remembering Jim Crow" – Minnesota Public Radio (multi-media)

- "Africans in America" – PBS 4-Part Series

- Black History Collection

- "the Rise and Fall of Jim Crow", 4-part series from PBS distributed by California Newsreel

- African-American Collection from Rhode Island State Archives