Astarte

Astarte (/əˈstɑːrtiː/; Greek: Ἀστάρτη, Astártē) is the Hellenized form of the Ancient Near Eastern goddess Astoreth (Northwest Semitic), a form of Ishtar (East Semitic), worshipped from the Bronze Age through classical antiquity. The name is particularly associated with her worship in the ancient Levant among the Canaanites and Phoenicians. She was also celebrated in Egypt following the importation of Levantine cults there. The name Astarte is sometimes also applied to her cults in Mesopotamian cultures like Assyria and Babylonia.

| Astarte | |

|---|---|

Goddess of fertility, sex, love, war | |

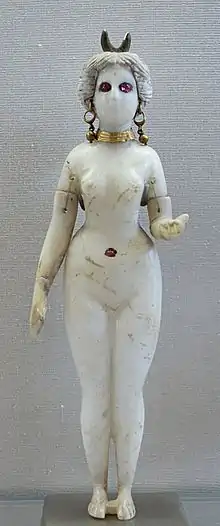

Statuette figurine of Astarte with a horned headdress, Louvre Museum, possibly the Great Goddess of Babylon (or Ishtar). From the necropolis of Hillah, near Babylon. | |

| Major cult center | Ugarit |

| Planet | Venus |

| Symbols | pentagram, sphinx, lion, dove, horse |

| Consort | El |

| Equivalents | |

| Greek equivalent | Aphrodite |

| Roman equivalent | Venus |

| Etruscan equivalent | Turan |

| Mesopotamian equivalent | Ishtar |

| Sumerian equivalent | Inanna |

| Deities of the ancient Near East |

|---|

| Religions of the ancient Near East |

Name

Astarte is one of a number of names associated with the chief goddess or female divinity of both Canaanite and Phoenicians.[1] She is recorded in Akkadian as As-dar-tu (𒀭𒊍𒁯𒌓D), the feminine form of Ishtar.[2] The name appears in Ugaritic as ʻAthtart or ʻAṯtart (𐎓𐎘𐎚𐎗𐎚), in Phoenician as ʻAshtart or ʻAštart (𐤏𐤔𐤕𐤓𐤕), in Hebrew as Ashtoret (עַשְׁתֹּרֶת).[2] The Hebrews also referred to the Ashtarot or "Astartes" in the plural. The Etruscan Pyrgi Tablets record the name Uni-Astre (𐌔𐌄𐌓𐌕𐌔𐌀𐌋𐌀𐌉𐌍𐌖).

Overview

Astarte was connected with fertility, sexuality, and war. Her symbols were the lion, the horse, the sphinx, the dove, and a star within a circle indicating the planet Venus. Pictorial representations often show her naked. She has been known as the deified morning and/or evening star.[2] The deity takes on many names and forms among different cultures, and according to Canaanite mythology, is one and the same as the Assyro-Babylonian goddess Ištar, taken from the third millennium BC Sumerian goddess Inanna, the first and primordial goddess of the planet Venus. Inanna was also known by the Aramaic people as the god Attar, whose myth was construed in a different manner by the people of Greece to align with their own cultural myths and legends, when the Canaanite merchants took the First papyrus from Byblos (the Phoenician city of Gebal) to Greece sometime before the 8th century by a Phoenician called Cadmus the first King of Thebes.

Astarte was worshipped in Syria and Canaan beginning in the first millennium BC and was first mentioned in texts from Ugarit. She came from the same Semitic origins as the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar, and an Ugaritic text specifically equates her with Ishtar. Her worship spread to Cyprus, where she may have been merged with an ancient Cypriot goddess. This merged Cypriot goddess may have been adopted into the Greek pantheon in Mycenaean and Dark Age times to form Aphrodite. It has been argued, however, that Astarte's character was less erotic and more warlike than Ishtar originally was, perhaps because she was influenced by the Canaanite goddess Anat, and that therefore Ishtar, not Astarte, was the direct forerunner of the Cypriot goddess. Greeks in classical, Hellenistic, and Roman times occasionally equated Aphrodite with Astarte and many other Near Eastern goddesses, in keeping with their frequent practice of syncretizing other deities with their own.[3]

Other major centers of Astarte's worship were the Phoenician city states of Sidon, Tyre, and Byblos. Coins from Sidon portray a chariot in which a globe appears, presumably a stone representing Astarte. "She was often depicted on Sidonian coins as standing on the prow of a galley, leaning forward with right hand outstretched, being thus the original of all figureheads for sailing ships."[4] In Sidon, she shared a temple with Eshmun. Coins from Beirut show Poseidon, Astarte, and Eshmun worshipped together.

Other centers were Cythera, Malta, and Eryx in Sicily from which she became known to the Romans as Venus Erycina. A bilingual inscription on the Pyrgi Tablets dating to about 500 BC found near Caere in Etruria equates Astarte with Etruscan Uni-Astre, that is, Juno. At Carthage Astarte was worshipped alongside the goddess Tanit.

The Aramean goddess Atargatis (Semitic form ʻAtarʻatah) may originally have been equated with Astarte, but the first element of the name Atargatis appears to be related to the Ugaritic form of Asherah's name: Athirat.

Allat the pre-Islamic Arabian deity and Astarte may have been assimilated to each other[5](p. 51), and the two were closely linked.[6] On one of the tesserae used by the Bel Yedi'ebel for a religious banquet at the temple of Bel the deity Allat was given the name Astarte ('štrt). The assimilation of Allat to Astarte is not surprising in a milieu as much exposed to Aramaean and Phoenician influences as the one in which the Palmyrene theologians lived.[7] Similar to Astarte, Allat was as well associated with morning star (Venus),[8][9][10][11][12] crescent,[13][14][15] war,[16][17] prosperity, and lions.[18][19]

In Ugarit

In the Baʿal Epic of Ugarit, Athirat, the consort of the god El, plays a role. She is clearly distinguished from Ashtart in the Ugaritic documents, although in non-Ugaritic sources from later periods the distinction between the two goddesses can be blurred; either as a result of scribal error or through possible syncretism.

In Egypt

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

|

._From_Thebes%252C_Egypt._18th_Dynasty._The_Petrie_Museum_of_Egyptian_Archaeology%252C_London.jpg.webp)

Astarte arrived in ancient Egypt during the 18th dynasty along with other deities who were worshipped by northwest Semitic people. She was especially worshipped in her aspect as a warrior goddess, often paired with the goddess Anat.

In the Contest Between Horus and Set, these two goddesses appear as daughters of Ra and are given as allies to the god Set, here identified with the Semitic name Hadad. Astarte also was identified with the lioness warrior goddess Sekhmet, but seemingly more often conflated, at least in part, with Isis to judge from the many images found of Astarte suckling a small child. Indeed, there is a statue of the 6th century BC in the Cairo Museum, which normally would be taken as portraying Isis with her child Horus on her knee and which in every detail of iconography follows normal Egyptian conventions, but the dedicatory inscription reads: "Gersaphon, son of Azor, son of Slrt, man of Lydda, for his Lady, for Astarte." See G. Daressy, (1905) pl. LXI (CGC 39291).

Plutarch, in his On Isis and Osiris, indicates that the King and Queen of Byblos, who, unknowingly, have the body of Osiris in a pillar in their hall, are Melcarthus (i.e. Melqart) and Astarte (though he notes some instead call the Queen Saosis or Nemanūs, which Plutarch interprets as corresponding to the Greek name Athenais).[20]

In Phoenicia

_01.jpg.webp)

In the description of the Phoenician pantheon ascribed to Sanchuniathon, Astarte appears as a daughter of Epigeius, "sky" (anc. Greek: Οὐρανός ouranos/ Uranus; Roman god: Caelus) and Ge (Earth), and sister of the god Elus. After Elus overthrows and banishes his father Epigeius, as some kind of trick Epigeius sends Elus his "virgin daughter" Astarte along with her sisters Asherah and the goddess who will later be called Ba`alat Gebal, "the Lady of Byblos".[21] It seems that this trick does not work, as all three become wives of their brother Elus. Astarte bears Elus children who appear under Greek names as seven daughters called the Titanides or Artemides and two sons named Pothos "Longing" (as in πόθος, lust) and Eros "Desire". Later with Elus' consent, Astarte and Hadad reign over the land together. Astarte puts the head of a bull on her own head to symbolize Her sovereignty. Wandering through the world, Astarte takes up a star that has fallen from the sky (a meteorite) and consecrates it at Tyre.

Ashteroth Karnaim (Astarte was called Ashteroth in the Hebrew Bible) was a city in the land of Bashan east of the Jordan River, mentioned in Genesis 14:5 and Joshua 12:4 (where it is rendered solely as Ashteroth). The name translates literally to 'Ashteroth of the Horns', with 'Ashteroth' being a Canaanite fertitility goddess and 'horns' being symbolic of mountain peaks. Figurines of Astarte have been found at various archaeological sites in Israel, showing the goddess with two horns.[22]

Astarte's most common symbol was the crescent moon (or horns), according to religious studies scholar Jeffrey Burton Russell, in his book The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity.[23]

Small terracotta votives are found of Dea Gravida which have an association with a seated pregnant Astarte.[24]

In Judah

Ashtoreth is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible as a foreign, non-Judahite goddess, the principal goddess of the Sidonians or Phoenicians, representing the productive power of nature. It is generally accepted that the Masoretic "vowel pointing" (adopted c. 7-10th centuries CE), indicating the pronunciation ʻAštōreṯ ("Ashtoreth," "Ashtoret") is a deliberate distortion of "Ashtart", and that this is probably because the two last syllables have been pointed with the vowels belonging to bōšeṯ, ("bosheth," abomination), to indicate that that word should be substituted when reading.[25] The plural form is pointed ʻAštārōṯ ("Ashtaroth"). The biblical Ashtoreth should not be confused with the goddess Asherah, the form of the names being quite distinct, and both appearing quite distinctly in the First Book of Kings. (In Biblical Hebrew, as in other older Semitic languages, Asherah begins with an aleph or glottal stop consonant א, while ʻAshtoreth begins with an ʻayin or voiced pharyngeal consonant ע, indicating the lack of any plausible etymological connection between the two names.) The biblical writers may, however, have conflated some attributes and titles of the two, as seems to have occurred throughout the 1st millennium Levant.[26] For instance, the title "Queen of heaven" as mentioned in Jeremiah has been connected with both (in later Jewish mythology, she became a female demon of lust; for what seems to be the use of the Hebrew plural form ʻAštārōṯ in this sense, see Astaroth).

Other associations

Some ancient sources assert that in the territory of Sidon the temple of Astarte was sacred to Europa. According to an old Cretan story, Europa was a Phoenician princess whom Zeus, having transformed himself into a white bull, abducted, and carried to Crete.[27]

Some scholars claim that the cult of the Minoan snake goddess who is identified with Ariadne (the "utterly pure")[28] was similar to the cult of Astarte. Her cult as Aphrodite was transmitted to Cythera and then to Greece.[29]

Byron used the name Astarte in his poem Manfred.

Her name is the second name in an energy chant sometimes used in Wicca: "Isis, Astarte, Diana, Hecate, Demeter, Kali, Inanna."[30]

In popular culture

See also

|

|

References

- Merlin Stone. When God Was A Woman. (Harvest/HBJ 1976)

- K. van der Toorn, Bob Becking, Pieter Willem van der Horst, Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, p. 109-10.

- Budin, Stephanie L. (2004). "A Reconsideration of the Aphrodite-Ashtart Syncretism". Numen. 51 (2): 95–145. doi:10.1163/156852704323056643.

- (Snaith, The Interpreter's Bible, 1954, Vol. 3, p. 103)

- Miller, Creighton J. (2009-01-16). "Judicial Staff Directory 2009. Edited by Claudia Driggins‐Henley. Washington, DC: CQ Press 2008‐. Last visited July 2008". Reference Reviews. 23 (1): 23–24. doi:10.1108/09504120910925580. ISSN 0950-4125.

- Jordan, Michael (2014-05-14). Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-0985-5.

- Teixidor, Javier (1979). The Pantheon of Palmyra. Brill Archive. ISBN 978-90-04-05987-0.

- Coulter, Charles Russell; Turner, Patricia (2013-07-04). Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-96390-3.

- Monaghan, Patricia (2009-12-18). Encyclopedia of Goddesses and Heroines [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-34990-4.

- Lazarus, William P.; Sullivan, Mark (2011-01-31). Comparative Religion For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-05227-3.

- Morey, Ph D. Dr Robert a (August 2011). The Islamic Invasion. Xulon Press. ISBN 978-1-61379-075-5.

- Taiz, Lincoln; Taiz, Lee (2016-12-07). Flora Unveiled: The Discovery and Denial of Sex in Plants. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-062773-7.

- Limited, Alamy. "Stock Photo - Allat, the Arab goddess of war, is the central figure on this stone relief from Hatra (once covered with thin sheets of gold or silver). She is flanked by two smaller female". Alamy. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- Jeffrey, David Lyle (1992). A Dictionary of Biblical Tradition in English Literature. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-3634-2.

- Loar, Julie (2010-11-22). Goddesses for Every Day: Exploring the Wisdom and Power of the Divine Feminine around the World. New World Library. ISBN 978-1-57731-951-1.

- Brzozowska, Zofia. "The Goddesses of Pre-Islamic Arabia (Al-Lāt, Al-'Uzzā, Manāt)". Byzantium and the Arabs: The Encounter of Civilizations from Sixth to Mid-Eighth Century, ed. Teresa Wolińska, Paweł Filipczak.

- Mernissi, Fatima (2009-03-05). Islam And Democracy: Fear Of The Modern World With New Introduction. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-7867-3100-8.

- Teixidor, Javier (1979). The Pantheon of Palmyra. Brill Archive. ISBN 978-90-04-05987-0.

- Maruf, Kanishk Tharoor and Maryam (2016-03-04). "Museum of Lost Objects: The Lion of al-Lat". BBC News. Retrieved 2020-03-14.

- Griffiths, J. Gwyn, Plutarch's De Iside et Osiride, pp. 325–327

- Je m'appelle Byblos, Jean-Pierre Thiollet, H & D, 2005, p. 73. ISBN 2 914 266 04 9

- Raphael Patai. The Hebrew Goddess. (Wayne State University Press 1990). ISBN 0-8143-2271-9 p. 57.

- Jeffrey Burton Russell. The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity. (Cornell University Press 1977). ISBN 0-8014-9409-5 p. 94.

- Markoe, Glenn (2000-01-01). Phoenicians. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-0520226142.

- Day, John (2002-12-01). John Day, "Yahweh and the gods and goddesses of Canaan", p.128. ISBN 9780826468307. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- Smith, Mark S. (2002-08-03). Mark S. Smith, "The early history of God", p.129. ISBN 9780802839725. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- Lucian of Samosata. De Dea Syria.

- Barry B. Powell. Classical Myth with new translation of ancient texts by H. M. Howe. Upper Saddle River. New Jersey. Prentice Hall Inc. 1998. p. 368.

- R. Wunderlich. The Secret of Creta. Efstathiadis Group. Athens 1987. p. 134.

- BURNING TIMES/CHANT, Charles Murphy, in Internet Book of Shadows, (Various Authors), [1999], at sacred-texts.com

Further reading

- Daressy, Georges (1905). Statues de Divinités, (CGC 38001-39384). II. Cairo: Imprimerie de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

- Scherm, Gerd; Tast, Brigitte (1996). Astarte und Venus. Eine foto-lyrische Annäherung. Schellerten. ISBN 3-88842-603-0.

- Harden, Donald (1980). The Phoenicians (2nd ed.). London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-021375-9.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger. "Astarte, Mistress of Horses, Lady of the Chariot: The Warrior Aspect of Astarte." Die Welt Des Orients 43, no. 2 (2013): 213–25. Accessed June 28, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/23608856.

- Sugimoto, David T., ed. (2014). Transformation of a Goddess: Ishtar, Astarte, Aphrodite. Academic Press Fribourg / Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen. ISBN 978-3-7278-1748-9. / ISBN 978-3-525-54388-7

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Astarte. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Astarte (goddess). |