Anglo-Russian invasion of Holland

The Anglo-Russian invasion of Holland (or Anglo-Russian expedition to Holland, or Helder Expedition) was a military campaign from 27 August to 19 November 1799 during the War of the Second Coalition, in which an expeditionary force of British and Russian troops invaded the North Holland peninsula in the Batavian Republic. The campaign had two strategic objectives: to neutralize the Batavian fleet and to promote an uprising by followers of the former stadtholder William V against the Batavian government. The invasion was opposed by a slightly smaller joint Franco-Batavian army. Tactically, the Anglo-Russian forces were successful initially, defeating the defenders in the battles of Callantsoog and the Krabbendam, but subsequent battles went against the Anglo-Russian forces. Following a defeat at Castricum, the Duke of York, the British supreme commander, decided upon a strategic retreat to the original bridgehead in the extreme north of the peninsula. Subsequently, an agreement was negotiated with the supreme commander of the Franco-Batavian forces, General Guillaume Marie Anne Brune, that allowed the Anglo-Russian forces to evacuate this bridgehead unmolested. However, the expedition partly succeeded in its first objective, capturing a significant proportion of the Batavian fleet.

| Anglo-Russian invasion of Holland | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Second Coalition | |||||||

Anglo-Russian troops departing Den Helder | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 25,000 | 40,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

7,000 killed, wounded or captured 25 ships lost | 18,000 killed, wounded or captured | ||||||

Background

In the 1780s, a pro-French Patriot rebellion failed to establish a democratic Dutch republic without the House of Orange-Nassau, when the latter's power was restored following the 1787 Prussian invasion of Holland. The Dutch Republic, again ruled by the Orangists, had been a member of the First Coalition that opposed the revolutionary French Republic after 1792. In 1795, at the end of their Flanders Campaign, the forces of stadtholder William V of Orange, and his British and Austrian allies were defeated by the invading French army under General Charles Pichegru, augmented with a contingent of Dutch Patriot revolutionaries under General Herman Willem Daendels.[1] The Dutch Republic was overthrown; the stadtholder fled the country to London; and the Batavian Republic was proclaimed.[2]

Despite the conquest of the old Republic in 1795, the war had not ended; the Netherlands had just changed sides and now fully participated in the continuing conflagration, but its role had changed. France did not need its army so much as its naval resources, in which France itself was deficient.[3] In 1796, under the new alliance, the Dutch started a programme of naval construction. Manning the new ships was a problem, because the officer corps of the old navy was staunchly Orangist. People like the "Hero of Doggerbank" Jan Hendrik van Kinsbergen honourably withheld their services. The new navy was therefore officered by people like Jan Willem de Winter, who were of the correct political hue, but had only limited experience. This directly led to the debacles of the surrender at Saldanha Bay in 1796, and of the Battle of Camperdown in 1797. At Camperdown the Batavian navy behaved creditably, but this did not lessen the material losses, and the Republic had to start its naval construction programme all over again.[4] This programme soon brought the Batavian navy up to sufficient strength that Great Britain had to worry about its potential contribution to a threatened French invasion of England or Ireland.[5]

The First Coalition broke up in 1797, but Britain soon found a new ally in Emperor Paul I of Russia. The new Allies scored some successes in the land war against France, especially in the puppet Cisalpine Republic and Helvetic Republic where the armies of the Second Coalition succeeded in pushing back the French on a broad front in early 1799. The British, especially the Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger, were eager to maintain this momentum by attacking at other extremes of the French "empire". The Batavian Republic seemed an opportune target for such an attack, with the Prince of Orange lobbying hard for just such a full military effort to reinstate him, and with Orangist agents leading the British to believe that France's hold over the Batavian Republic was weak and that a determined strike by the British towards Amsterdam would lead to a massive uprising against the French. An added incentive was that a combined campaign against the Dutch had been a condition of the agreement with the Russians of 28 December 1798.[6] In that agreement, Emperor Paul I had placed 45,000 Russian troops at the disposal of the Coalition in return for British subsidies. This convention was further detailed in an agreement of 22 June 1799, whereby Paul promised to furnish a force of seventeen battalions of infantry, two companies of artillery, one company of pioneers, and one squadron of hussars for the expedition to Holland; 17,593 men in total. In return, Britain promised to pay a subsidy of £88,000, and another £44,000 a month when the troops were in the field. Great Britain would itself furnish 13,000 troops and supply most of the transport and naval-escort vessels.[7]

Campaign

From the outset, the joint expedition that was now planned should not be a purely military affair. Pitt assumed that, like the Italian and Swiss populations, the Dutch would enthusiastically support the invasion against the French. According to the British historian Simon Schama: "Once the Orange standard had been raised, he seems to have believed that the Batavian army would go over to the forces of the Coalition to the last man and that its Republic would collapse under the barest pressure."[8] Ultimately, these expectations were disappointed.[9]

Preparations

The British forces were assembled in the vicinity of Canterbury under the command of Lieutenant-General Sir Ralph Abercromby. They were mostly made up of volunteers from the militia who had recently been permitted to join regular regiments. While a British transport fleet under Admiral Home Riggs Popham sailed to Reval to collect the Russian contingent, the mustering of the British troops progressed smoothly. It was therefore decided not to wait for the return of Popham but to send a division under Abercromby to establish a bridgehead on which it was hoped the Russian troops and a second division under the designated supreme commander of the expedition, the Duke of York, could easily be disembarked.[10]

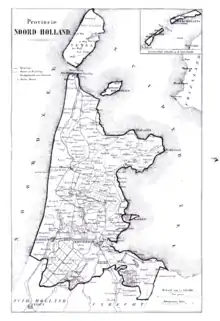

The question was where this amphibious landing could best take place. Several locations on the Dutch coast were considered. Many strategists preferred either the mouth of the Meuse river, or the vicinity of Scheveningen, both of which offered an opportunity to quickly deploy the attacking forces and threaten the supply lines of the French army of occupation in the Batavian Republic.[11] These locations had as a severe drawback the dangerous shoals before the Dutch coast that made it difficult to navigate these waters. The extreme north of the North Holland peninsula did not have this drawback and a landing here could thus be supported by British sea power in the North Sea. It also recommended itself to the planners of the invasion, because the area was only lightly fortified; a large part of the Dutch fleet (an important objective of the expedition) was based nearby and might be at least dislocated, if the landing was successful; and the terrain seemed to promise the possibility of an easy advance on the important strategic objective of the city of Amsterdam. The area south of Den Helder was therefore selected as the landing place.[12]

The British did not make a secret of their preparations. The authorities in France and the Batavian Republic were therefore aware of them. The intended landing location was not known to them and they were therefore forced to spread their forces thinly to guard against all eventualities. The Batavian army at the time consisted of two divisions (each of about 10,000 men), one commanded by Lieutenant-General Daendels, the other by Lieutenant-General Jean-Baptiste Dumonceau. The latter had taken up positions in Friesland and Groningen to guard against a landing from the Wadden Sea or an incursion from the East. Daendels indeed was positioned in the northern part of North Holland, with headquarters at Schagen. The French troops (only 15,000 of the full complement of 25,000 troops that the Treaty of The Hague called for) were divided between Zeeland (another logical landing spot, where in 1809 the Walcheren Expedition took place), and the middle of the country, strung out between the coast and Nijmegen. The entire Franco-Batavian army was placed under the command of the French General Brune.[13]

Landing at Callantsoog and the surrender of the Batavian squadron

The invasion met with early success. The depleted Dutch fleet, under Rear-Admiral Samuel Story, evaded battle, leaving the disembarkation of the British troops near Callantsoog on 27 August 1799, unopposed. General Daendels was defeated in the Battle of Callantsoog when he tried to prevent the establishment of a bridgehead by the division under General Abercromby. This was due to the fact that he was forced to divide his forces, because of the nature of the field of battle, a narrow band of dunes, bordered by the North-Sea beach on one side, and a swamp on the other. Due to communication problems, his right wing was never fully engaged, and the forces of his left wing were fed piecemeal into the battle. The British made very good use of the support their gunboats could offer from close inshore. The naval gunfire inflicted heavy losses on the Dutch.[14]

Daendels then concluded that the Helder fortresses were untenable and evacuated their garrisons, thereby offering the invaders a fortified base. This decision proved disastrous for Dutch morale: the sight of the flag of the hereditary stadtholder, who soon joined the expedition, further undermined the already questionable loyalty of the Dutch fleet in the Zuyder Zee. When Admiral Story belatedly decided to engage the British fleet, he had a full-fledged mutiny on his hands, where the Orangist sailors were led by their own officers, Captains Van Braam and Van Capellen.[15] This led to the Vlieter Incident, the surrender on 30 August of the fleet with 632 guns and 3700 men to Admiral Andrew Mitchell, without a shot being fired. Later, the Prince went aboard Story's flagship, Washington to receive the accolades of the mutineers.[16]

Arnhem and Krabbendam

The Dutch land forces were less amenable to the Prince's powers of persuasion, and neither was the civilian population in North Holland. If anything, the effect of the invasion was to unify the divided Republic against the invader. The Prince's arrogant proclamation, peremptorily ordering the Dutch people to rally to Orange, was also not calculated to convince the Dutch of the wisdom of a restoration of the Stadholderate.[17] It was therefore not surprising that the call for an uprising by the old Stadtholder himself from Lingen met with indifference by the people. A motley band of Orangist émigrés at the Westervoortsche Bridge near Arnhem, was easily put to flight on September 4 by a small detachment of the Batavian National Guard, proving that the invaders had to do the work themselves.[18] Other Orangist incursions in the eastern Netherlands and Friesland met with even less success. Nevertheless, the Uitvoerend Bewind of the Batavian Republic declared martial law and under these emergency measures an aristocratic partisan of the stadtholder, the freule (baroness) Judith Van Dorth tot Holthuizen was convicted of sedition and executed.[19]

Meanwhile, the Franco-Batavian forces on the North Holland front were being reinforced. General Brune brought up a French division under General Dominique Vandamme and ordered General Dumonceau to bring up the main part of his 2nd Batavian division in forced marches from Friesland. The latter arrived on 9 September at Alkmaar. The Franco-Batavian army now had about 25,000 men available against about 20,000 for the British. In view of this numerical superiority, and the fact that reinforcements for the British were expected any day, Brune decided to attack Abercromby's position.[20]

The British prevailed at the Battle of Krabbendam near Alkmaar on 10 September, where the Batavians and French were routed. This defeat was partly due to sloppy staffwork that allocated one narrow road to the columns of both Batavian divisions that were supposed to converge on the hamlet of Krabbendam.[21] This hamlet sat astride one of the few entry roads to the Zijpe polder in which Abercromby had set up an armed camp. The polder formed a natural redoubt with its dike acting as a rampart and its circular drainage canal as a moat.[22] The straight and narrow road through Krabbendam formed one of the few easy entries, but it was easily defensible also. The original plan had this entry point attacked by both Batavian divisions, but because Daendels' division was forced to take a more easterly route, only the division of Dumonceau was brought to bear. This division could not be fully deployed due to the nature of the terrain and the Batavian forces were therefore again fed piecemeal into the battle. They were unable to prevail over the valiant defence of the British 20th Foot. Elsewhere, the French division of General Vandamme was likewise unable to overcome the obstacles of the canal and the dike behind it, that protected the British troops. Vandamme therefore failed to turn Abercromby's right flank as planned.[23]

With Britain having naval superiority, both on the North Sea and the Zuider Zee, British reinforcements under the Duke of York (who assumed supreme command) and Russian troops under general Ivan Ivanovitch Hermann von Fersen could easily be landed at Den Helder. The combined forces soon achieved numerical superiority with 40,000 men against 23,000 of the depleted Franco-Batavian army.[24]

Bergen

The Duke of York decided to exploit this numerical superiority as soon as possible. He therefore prepared for an attack on a broad front. To understand the problems this attack encountered one needs to understand the peculiar nature of the terrain. The North Holland peninsula is bordered on the North-Sea side by a beach and a broad band of dunes (except for a short stretch south of Petten, where only a large dike defends the hinterland against flooding). Next to the dunes is a band of high land that can easily be traversed by a marching army. Further east, the terrain changes to former bogland and other low-lying areas consisting of former lakes that had been drained by the Dutch in the 17th century. These low-lying areas were criss-crossed by ditches and larger drainage canals, needed in the water-management of the area, that formed serious impediments to manoeuvring forces, even when they were not inundated. Such inundations were increasingly performed by the Dutch engineers the more the campaign progressed, to deny more and more freedom of movement to the Anglo-Russian forces. At the time of the Battle of Bergen that commenced on 19 September, most of those inundations were not yet completed, so that at that time the main obstacles were still the watercourses.

_forces_near_Bergen%252C_by_Dirk_Langendijk_(1748_-_1805).jpg.webp)

The Duke of York drew up a daring plan of attack that amounted to an attempt at double envelopment of the Franco-Batavian army. He divided his forces over four columns. The rightmost column, under the Russian Lieutenant-General Hermann, with 9,000 Russians and 2,500 British troops, starting from Petten and Krabbendam, had as objective the village of Bergen. Next to it marched an Anglo-Russian force of 6,500 troops under Lieutenant-General Dundas with as objective Schoorldam. The next column, 5,000 men under Lieutenant-General Pulteney had as objective the area of Langedijk with the hamlets of Oudkarspel and Heerhugowaard. Finally, the fourth column, 9,000 infantry and 160 cavalry under Lieutenant-General Abercromby, was intended to turn the Franco-Batavian right flank, by first attaining Hoorn and then thrusting southward to Purmerend.[25]

The plans of the Anglo-Russian troops were lacking. The attack was supposed to start at dawn on the 19th, but the Russian right wing already started at 3 AM in pitch darkness. Though they gained an early advantage against the surprised French troops on the Franco-Batavian left wing, they also suffered needless losses through friendly fire, as the troops were unable to distinguish friend from foe. They eventually gained Bergen, but were counter-attacked by French reinforcements marching north from Egmond aan Zee. These threatened to turn the Russian right wing by marching along the beach. The Russians, driven out of Bergen, retreated in some disorder to their starting positions because of this threat of being out-flanked. In the confusion general Hermann was made a prisoner of war. The attack of the right-wing pincer therefore was a dismal failure.[26]

The column of General Dundas (accompanied by the commander-in-chief, the Duke of York) made only slow progress after it started its advance at dawn, because of the watercourses it encountered that were difficult to cross, as the defenders had removed the bridges. While they were slowly advancing on Schoorldam, the defender of that position, General Dumonceau with the 2nd Batavian division, had time to launch a diversionary attack on the Russians attacking Bergen, which contributed greatly to the confusion in the Russian ranks. When Dundas finally arrived at Schoorldam, Dumonceau was wounded by grapeshot. What exactly happened on the Dutch side after that is unclear as his replacement, General Bonhomme, failed to make an after-battle report. The upshot was that the division fell back in some disorder on Koedijk. The British failed to exploit this retreat, due to a counter-attack from the Dutch, but mainly because the rout of the Russian troops on the right wing also forced a withdrawal in the form of an orderly rear-guard action of the troops of York and Dundas. They also eventually returned to their starting positions.[27]

The third column, with Generals Pulteney, Don and Coote, likewise found the terrain difficult. This column was forced to use the road on a dike, called the Langedijk (long dike) that divides several polders. This dike was flanked on the right hand by a deep drainage canal, and on the other side the many ditches in the land also hindered easy deployment. The road led to the village of Oudkarspel where the 1st Batavian division of General Daendels had built some fieldworks (the Dutch complained that Brune had prohibited the full development of fortifications, which made the defence more difficult). The first attack on this strongpoint by Pulteney ended in disaster with the British fleeing in panic until they could be rallied behind another dike that gave some cover against the Dutch artillery fire. Several other British frontal attacks were also repulsed with great loss, and an encircling movement proved impracticable due to the canal. General Daendels made the mistake of ordering an under-strength sally from his redoubt by 100 grenadiers. Not only was this easily repulsed, but the rout of the grenadiers enabled the pursuing British, following hot on their heels, to penetrate the Dutch entrenchments and rout the entire group of defenders. This rout could only be stopped at the end of the Langedijk. The retreating troops suffered very heavy losses due to British artillery fire. Daendels finally personally led a counter-attack with only one battalion of grenadiers, but by then the debacle on the British right wing had been communicated to Pulteney, who therefore was already withdrawing to his starting position. The British therefore made no net territorial gains, but they had dealt the Batavians heavy losses in casualties and prisoners.[28]

Finally, the long march of the fourth column under General Abercromby went completely unopposed. He reached Hoorn without mishap and managed to surprise the weak garrison at this city. Hoorn was occupied and briefly the locals displayed the colours of the stadtholder. The planned march south from Hoorn, which was the point of the entire manoeuvre, as it would have enabled Abercromby to turn the right flank of the Franco-Batavian army, proved impossible because of the obstacles the defenders had prepared (This explains why Abercromby had not encountered opposition on his march to Hoorn). After the retreat of the other columns Abercromby received orders to evacuate Hoorn and likewise go back to his starting position. The citizens of Hoorn quickly took down their orange flags again. Abercromby's work had therefore been completely in vain, and would have been so even if the attack on the right wing had been successful. His route was simply too circuitous to be successful. A more direct route might have offered a better chance of success.[29]

In sum, neither side made any territorial gains in this battle. The losses in personnel were substantial on both sides, and appear to have been about equal.[30]

Alkmaar

After the surrender of the Batavian squadron on 30 August, the British fleet had become master not just of the North Sea, but also of the Zuider Zee. Remarkably, the British had not made use of this advantage (and of the psychological consequences of the surrender for Batavian morale) to force the issue, for instance by making an amphibious landing near Amsterdam. General Krayenhoff, who at the time was in charge of improvising the defences of that city, points out that for a few days Amsterdam lay quite defenseless against such an attack. In his opinion the campaign might have ended then and there. The British fleet had remained strangely passive. This changed in the days after the Battle of Bergen when the British belatedly occupied the undefended ports of Medemblik, Enkhuizen, and Hoorn, at the same time mastering the West Friesland region between these ports. A number of islands in the Zuider Zee were also occupied, but by then the window of opportunity to capture Amsterdam had closed.[31]

On land, the initiative still lay with the expeditionary force, that received new Russian reinforcements after 19 September that made up for at least the Russian losses. The Duke of York did not press the attack for about two weeks because of bad weather, and this afforded an opportunity to the defenders to complete their inundations and other defences. The Langedijk now became a narrow "island" in a shallow lake with the now-improved fortifications of Oudkarspel acting as an impenetrable "Thermopylae." The 1st Batavian division of Daendels still defended this part of the front, but Brune was able to shift large parts of that division (especially its cavalry units) to his other wing.[32] The eastern seaboard of the peninsula was made even more impenetrable by inundations, and a secondary line of entrenchments was prepared between Monnickendam and Purmerend. The main effect of these defensive preparations was, that the low-lying eastern part of the peninsula became impassable to the expeditionary force and that henceforth operations would be limited to the relatively narrow band, consisting of the beach, dunes and the plain directly adjacent to them, roughly the area between Alkmaar and the sea.[33]

The weather improved in early October and the Duke of York then made his plan for what was to become known as the Battle of Alkmaar of 2 October 1799 (though "Second Bergen" would seem more appropriate, as the former city never was involved, and the latter village again became the centre of the battle). The Duke of York's former left wing, under General Abercromby, was moved over completely to the extreme right wing, with the other columns moving to the left to make room. This had the effect of placing exclusively-British formations on both wings (Pulteney and Abercromby) and having mixed Anglo-Russian formations in the column next to Abercromby's under the new Russian commander, General Ivan Essen. The fourth column (between Pulteney and Essen) was made up of British troops under General Dundas. York intended to have all three columns on the right wing converge on the Franco-Batavian left wing, which consisted of the French division of Vandamme near the coast (the 2nd Batavian division of Dumonceau -now commanded by Bonhomme- was placed in the Franco-Batavian center). The division of Pulteney was used as a screening force of the left wing, to deter Daendels.[34]

The plan of attack could now be characterized as one of "single envelopment," with Abercromby's column intended to turn the French left wing by marching along the beach. To this end the start of the advance had to be delayed until 6.30 AM, when low tide allowed Abercromby to use the beach.[35] The Anglo-Russian centre advanced slowly but steadily, much hindered by the difficult terrain of the dunes on the right and the water-course-ridden plain between the dunes and the Alkmaar canal on the left. The Franco-Batavians fought a steady rear-guard action, falling back on Bergen (the French) and Koedijk (the Batavians), where they made a stand. In the afternoon the British brigade in Essen's column (General Coote) seemed to make a sudden dash in the dunes, but got too far ahead of the remainder of Essen's column, which followed far more slowly, and the French launched a spirited counter-attack from Bergen in two columns under Generals Gouvion and Boudet to exploit the gap. They were driven back with some difficulty, but managed to retain the village of Bergen for the remainder of the day, despite continued Anglo-Russian attacks.[36]

Meanwhile, the column of General Abercromby made very slow progress along the beach, mostly because the tide was coming in again, which narrowed the beach to a very small band, consisting of loose sand. The troops and horses were suffering severely from fatigue and thirst. In the course of the afternoon they were observed by the French who brought up sharpshooters at first, who caused a number of casualties, especially of the officers. The French sent more and more substantial reinforcements through the dunes and eventually General Vandamme brought up a substantial cavalry force which he led personally in a charge against the British horse-artillery batteries that temporarily fell into French hands. This cavalry attack was eventually repulsed by a counter-attack led by Lord Paget, who drove the French all the way back to Egmond aan Zee.[37]

By then night had fallen and major operations stopped. Abercromby had by then passed the latitude of Bergen, so theoretically the French were outflanked there. Though he did not have the strength to exploit this position at the time, General Brune felt sufficiently threatened by this that he decided to order a general strategic retreat from Bergen, and from his other positions of 2 October, on the next morning. Both the French and the Batavians now fell back on their secondary line. Daendels retreated to the prepared positions at Monnickendam and Purmerend, after which Krayenhoff completed the inundations in front of this line. Bonhomme and Vandamme occupied a new line between Uitgeest, Castricum and Wijk aan Zee. This guarded the narrowest part of the North Holland peninsula, as in those days the IJ still bisected the province. Here they awaited the next move of the enemy.[38]

Castricum

With the retreat of the Franco-Batavian army the greater part of the North Holland peninsula was now in Anglo-Russian hands, at least theoretically. Large parts of the country, the former lakes of the Beemster, Schermer, and Wormer, had been flooded, depriving the British of their rich farmland and the supplies that might have been obtained there. In consequence, most supplies had to be landed at Den Helder and then brought forward with much difficulty across roads that were almost impassable because of the incessant rains. Beside the troops, the hungry mouths of about 3,000 deserters and mutineers that the Hereditary Prince hoped to form into a Dutch Brigade, but that were not employed by the British,[39] had to be fed. Provisions were running short.[40]

The Duke of York (now headquartered in Alkmaar, which city had opened its gates to him on 3 October) wasted as little time as possible in pressing the offensive. He knew that Brune had been reinforced with six French battalions, brought up from Belgium. His own forces were in steady decline, especially because of sickness.[41] By the start of the next phase of the campaign: the Battle of Castricum of 6 October, his effective force amounted to no more than 27,000.[42]

Brune had divided his left wing into three divisions: Gouvion near Wijk aan Zee in the dunes; to his right Boudet around Castricum; and the 2nd Batavian division, still commanded by Bonhomme, around Uitgeest. In front of this entrenched line there were French outposts, in Bakkum and Limmen, commanded by brigadier-general Pacthod. On the morning of 6 October these were attacked by the now-familiar three columns: Abercromby along the beach, Essen in the middle and Dundas on the left, while Pulteney still rather uselessly masked Daendels. The Anglo-Russians of Essen's column easily drove out the French outposts. The Duke of York appears to have had nothing more in mind than an armed reconnaissance, but their early success tempted the Russians to attack Castricum in force and this village was tenaciously defended by Pacthod. The village changed hands several times that day as Brune had Boudet bring up reinforcements. The fighting attracted reinforcements from the columns of Dundas and Abercromby, the latter personally bringing up his reserve-brigade to attack Castricum late in the afternoon[43]

Brune then ordered a bayonet attack which drove back the British and Russians in disorder. They were pursued in the direction of Bakkum by French cavalry under General Barbou and a rout might have ensued had not the light dragoons of Lord Paget intervened in a surprise charge from a hidden dune valley. The French cavalry was now routed in its turn. They drew along the exhausted Franco-Batavian troops that had only shortly before retaken Castricum and a disorderly retreat was about to start[44]

The advance of the British was broken by a counter-attack of the Batavian hussars under Colonel Quaita.[45] This turned the tide in the battle. The Anglo-Russian troops in their turn now broke and retreated in disorder to Bakkum and Limmen, pursued by the Franco-Batavian cavalry. Only the quickly falling darkness ended the slaughter.[46]

All this time the French of General Gouvion and the British column of Abercromby had been fighting a separate battle near the beach and in the dunes. Apart from an artillery duel, in which the Batavian artillery of Gouvion inflicted heavy losses on the British,[47] this remained rather static, especially after Abercromby left with the British reserve to join Essen. The fight intensified against the evening when Abercromby returned and tried to attack but Gouvion held his line.[48]

On the Batavian right wing of General Daendels, absolutely nothing happened that day, as the inundations made his lines impenetrable. There was a strange incident when the British General Don, under cover of a flag of truce, tried to get permission to cross the Batavian lines on a mission to the Batavian government. As on the Batavian left wing the battle had clearly started, Daendels considered this an abuse of the flag of truce. Besides, Don turned out to have papers on his person that could be considered to be of a seditious nature. Daendels therefore arrested Don as a spy and sent him to Brune's headquarters. Don was incarcerated in the fortress of Lille and only years later exchanged for the Irish rebel James Napper Tandy.[49]

Anglo-Russian retreat and capitulation

Though on the night of 6 October the two armies were back in their starting positions (though the outposts in Bakkum and Limmen remained in British hands), and the Anglo-Russian losses had not been devastating (though they were about double the Franco-Batavian losses), the Duke of York now convened a council of war with his lieutenants-general. The outcome of this conference was that the Anglo-Russian army withdrew completely to the original bridgehead of the Zijpe polder, relinquishing all terrain that had been gained since 19 September. The cities of Hoorn, Enkhuizen and Medemblik were also evacuated and the following Batavian troops could only just prevent the burning of the warehouses with naval stores in those cities by the British. The retreat was executed in such haste that two field hospitals full of British wounded were left in Alkmaar, together with 400 women and children of soldiers.[50]

The strategic withdrawal was completed on 8 October, though Prince William of Gloucester, retreating from Hoorn, fought a rearguard action against Daendels in the following days. By mid-October, the situation of before 19 September had been restored, the Anglo-Russians ensconced in their natural redoubt and the Franco-Batavians besieging them. The weather had taken a turn for the worse, and early winter gales made provisioning by sea difficult. The Duke of York was now faced with the prospect of a winter siege in a situation in which his troops might well face starvation (on 13 October provisions for only eleven days were still available[51]). He therefore decided to approach Brune with a proposal for an honourable capitulation transmitted by general Knox on 14 October.[52]

The following negotiations were short. Brune at the behest of the Batavian government at first demanded the return of the captured Batavian squadron. The Duke of York countered with a threat to breach the dike near Petten, thereby inundating the countryside around the Zijpe polder. Though General Krayenhoff was not impressed by this threat (after all, he had spent the previous weeks flooding most of the peninsula himself, and knew that the process could be reversed without too much difficulty) and so advised Brune, the latter was more easily impressed (or feigned this; Krayenhoff also darkly mentions a gift of a number of "magnificent horses" by the Duke to Brune as a possible deal-clincher) and soon agreed to a convention that was very favourable to the Anglo-Russians. In this Convention of Alkmaar that was signed on 18 October no more mention was made of the return of the ships. The Anglo-Russian troops and the Orangist mutineers were granted an undisturbed evacuation, which had to be completed before 1 December. There would be an exchange of 8,000 prisoners of war, including Batavian seamen, that had been captured at the Battle of Camperdown (Admiral De Winter, who had been paroled earlier, was specifically included). The British promised to return the fortresses at Den Helder with their guns in good order. Except for the return of their prisoners of war, the Batavians thought they had got the worst of this exchange, but they were powerless to get a better deal.[53]

An armistice went into force immediately and the evacuation was completed on 19 November, when General Pulteney left with the last British troops.[54] The Russians sailed along the British coast until they reached the Channel islands where they spent the winter, returning to St.Petersburg in August 1800.[55]

Aftermath

The capitulation was favourable to the British and their Russian allies. They extracted their troops unharmed so that these could fight again in other theatres of war. The initial British reports about the conduct of the Russian troops had been highly unfavourable, reason for Czar Paul to dishonour them. The Duke of York thought this too harsh, and he sent a letter to Paul specifically exculpating a number of the Russian regiments.[56]

The British public and Parliament at first were well pleased with the conduct of the British troops. Both Admiral Mitchell and General Abercromby were voted the thanks of Parliament and both received honorary swords, valued at 100 guineas, from the City of London. Mitchell was appointed Knight Companion of the Order of the Bath (KB).[57] When the failure of the expedition had sunk in and its cost had become clear, popular sentiment changed. In Parliament, the leader of the Opposition, Richard Brinsley Sheridan severely castigated the government in a speech, delivered on 9 February 1800, in the House of Commons[58]

For the Batavian Republic the material losses sustained during the expedition were severe. The Batavian navy lost 16 ships-of-the-line, five frigates, three corvettes, and one brig, out of a total of 55 ships. This surrender technically was accepted in the name of the Stadtholder by the British, a conceit they adopted for diplomatic reasons, but a number of the ships were later "purchased" from the Stadtholder by the Royal Navy.[59]

In France the expedition may have contributed (together with the initial French military reversals in Switzerland) to the fall of the Directoire. They were driven from power in the coup d'état of 18 Brumaire by Napoleon Bonaparte.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anglo-Russian invasion of Holland (1799). |

References

- Schama, pp. 178–190

- Schama, pp. 190–192

- Schama, p. 235

- Schama, pp. 282, 292

- Plans for an invasion of Ireland, using a Batavian squadron, had reached an advanced stage in 1797; Schama, pp. 278–279, 281

- Schama, p. 390

- Campaign, p. 2; Schama, p. 390

- Schama, p. 391

- Campaign, p. 70; Ehrman, p. 257

- Campaign, p. 4–6

- Campaign, p. 4

- Campaign, pp. 4–5

- Campaign, pp. 5–6

- Krayenhoff, pp. 58–76

- The latter would after his exile in England become a vice-admiral in the new Royal Netherlands Navy and lead a Dutch squadron at the Bombardment of Algiers in 1816.

- Schama, pp. 393-394

- The Dutch historian Colenbrander, not unduly antagonistic to the Prince, ruefully notes that a similar proclamation from Admiral Adam Duncan in which the stadtholder was called the "legitimate sovereign" of the Dutch people, seemed calculated to annoy even staunch supporters of the Prince;Colenbrander, p. 212

- Schama, p. 394

- Krayenhoff, pp. 97–101; see for particulars about the execution of freule Judith van Dorth tot Holthuizen: Dorth, Judith van

- Krayenhoff, pp. 110–115

- Krayenhoff, p. 118, 127

- Krayenhoff, pp. 105–108

- Campaign, pp. 22–23

- Krayenhoff, p. 131, 134

- Krayenhoff, pp. 134–137

- Krayenhoff, pp. 137–142

- Krayenhoff, pp. 143–147

- Krayenhoff, pp. 147–154

- Krayenhoff, pp. 154–157, 161

- Krayenhoff, p. 158

- Krayenhoff, pp. 165–168; Campaign pp. 37–38

- Krayenhoff, p. 182; the British seem to have been under the illusion that they could prevent such a shift by masking Daendels with the division of general Pulteney; Campaign, p. 43

- Krayenhoff, pp. 169–171;Campaign, pp. 39–40

- Campaign, pp. 41–44; Krayenhoff, pp. 171–174

- Krayenhoff, pp. 175–176

- Campaign, pp. 44–48; Krayenhoff, pp. 176–182

- Campaign, pp. 49–51; Krayenhoff, pp. 182–184

- Krayenhoff, pp. 188–190

- The regiments formed by the Prince were not used in the Helder campaign. Plans to use them for a descent on Friesland came to nothing for lack of transportation.Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts (1907) Report of the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts. Vol. 17, p. 96

- Campaign, p. 57; Jomini, p. 211

- Malaria had long been endemic in North Holland and was only eradicated in the 20th century. The troops (on both sides) may therefore have suffered from malarial fevers. But there also may have been a typhoid epidemic, possibly at the same time, as both illnesses present similar symptoms. Cf. Thiel, P.H. van (1922) Anopheles en Malaria in Leiden en Naaste Omgeving (diss.) in Pamphlets on Protozoology (Kofoid Collection), p. 2

- Campaign, p. 57

- Jomini, p. 213

- Jomini, p. 214

- According to his own after-battle report, Quaita ordered the charge on his own initiative: "Quaita, Francois," in: Molhuysen, P.C., Blok, P.J. (eds.) (1921) Nieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch Woordenboek. Deel 5, p. 545; Jomini does not mention Quaita and ascribes the entire charge to Brune personally, though he mentions the hussars; Jomini, p. 215; Krayenhoff, p. 202, gives the honour to Quaita.

- Jomini, p. 215

- Krayenhoff, p. 204

- Jomini, pp. 215– 216

- Krayenhoff, pp. 208–210

- Krayenhoff, pp. 210, 212–214; Campaign, pp. 60–63

- Krayenhoff, p. 224

- Campaign, pp. 63–64

- Krayenhoff, pp. 224–237

- Krayenhoff, p. 258; Krayenhoff, then commander of the Batavian Engineers recounts how he inspected the fortresses personally on behalf of the Franco-Batavian command to check compliance with the capitulation; Krayenhoff, ch. IX

- Puntusova, Galina. "Гатчинские гренадеры на Британских островах. Часть 1". history-gatchina.ru.

- Campaign, p. 69

- "No. 15220". The London Gazette. 7 January 1800. p. 25.

- Campaign, p. 70; Krayenhoff, p. 260

- W.M. James,The Naval History of Great Britain: During the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Vol. 2 1797-1799, Stackpole Books 2002, ISBN 0-8117-1005-X, p. 310

Sources

- (in Dutch) Colenbrander, H.T. (1908) De Bataafsche Republiek

- The campaign in Holland, 1799, by a subaltern (1861) W. Mitchell

- Ehrman, J. (1996) The Younger Pitt: The consuming struggle. Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-2754-6

- Harvey, Robert. War of Wars: The Epic Struggle Between Britain and France 1789-1815. London, 2007

- Hague, William. Pitt the Younger.Random House, 2005 ISBN 1-4000-4052-3, ISBN 978-1-4000-4052-0

- Intelligence Division, War Office, Great Britain, British minor expeditions: 1746 to 1814. HMSO, 1884

- (in French)Jomini, A.H. (1822) Histoire Critique Et Militaire Des Guerres de la Revolution: Nouvelle Edition, Redigee Sur de Nouveaux Documens, Et Augmentee D'un Grand Nombre de Cartes Et de Plans (tome xv, ch. xciii)

- (in Dutch) Krayenhoff, C.R.T. (1832) Geschiedkundige Beschouwing van den Oorlog op het grondgebied der Bataafsche Republiek in 1799. J.C. Vieweg

- Schama, S. (1977), Patriots and Liberators. Revolution in the Netherlands 1780-1813, New York, Vintage books, ISBN 0-679-72949-6

- Urban, Mark. Generals: Ten British Commanders Who Shaped the World. Faber and Faber, 2005.