Ashley Library

The Ashley Library is a collection of original editions of English poets from the 17th century onwards, including their prose works as well as those in verse, collected by the bibliographer, collector, forger, and thief Thomas James Wise.[2][3] The library was sold to the British Museum by his widow, Frances Louise Greenhaigh Wise, in 1937 for £66,000.[4][upper-alpha 1][upper-alpha 2] It was named after the street in which Wise lived when he started the collection (Ashley Road, Hornsey Rise).[4][7]

In book-collecting as in other things, the sum of all is that what interests you is what concerns you. Now to this end and purpose alone I also hold the Ashley Library to be wonderful, but it has an added wonder in that it reveals so exquisite a discrimination and so great a reverence for our masterpieces of literature... the great catalogue of his life's work and love, which is in effect a history of English literature during the last 300 years, may well appear as a blazing star, or an Angel, to his sight.

Scope

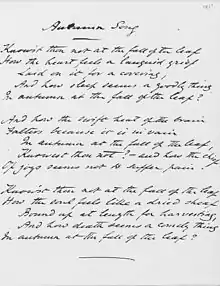

The Ashley Library is recognized as one of the most important collections of 19th-century English literary manuscripts.[9] The collection spans the period from Coleridge to Conrad, with the emphasis on poetical manuscripts and the correspondence of writers, critics, collectors, and bibliographers. The collection is strong in manuscripts of the Younger Romantics and of the Pre-Raphaelites, together with Swinburne. Wise's lack of scholarship and his practice of dispersing related manuscripts throughout the collection, made it a particularly difficult library to catalog .[9]

History

The original collection consisted of 7,000 volumes with the bookcases used to hold them. When the British Museum library cataloged the collection it was discovered that 200 volumes were missing, it is thought that these were sold by Wise in the 1920s.[4]

Part of the collection was pre-restoration drama which Wise had been collecting since 1900. These works were compared with the British Museum's former collection at which point it was discovered that over 200 book leaves were missing and 89 of these matching leaves were found in the Wise volumes. [upper-alpha 3] Henry Wrenn had built up a drama collection (housed in the University of Texas)[11] and Wise had helped with supplying these volumes, when the Texas authorities sent relevant volumes for comparison, 60 of these books were also found to have been completed with thefts from the British Museum library.

Though allegations were published against Wise of theft and forgery in 1934, it was not until 1959 that a detailed scientific investigation was published by the Bibliographic Society. The conclusion supported the theory that Wise must have known that some of the books leaves added to his collection were stolen and that it was probable that he would have taken the leaves himself.[upper-alpha 4]

References

Notes

- "The purchase consists of about 7,000 volumes, both printed and in manuscript, and no comparable addition to the British Museum Library has been made since 1846, when Thomas Grenville bequeathed his collection."[5]

- "The Ashley Library, which is to be kept together, printed books and manuscripts, is as yet unsorted and temporarily assembled in one of the newly constructed rooms in the West Wing of the Old Library. There it awaits detailed examination and the affixing of the official stamp to each book and document; after which it will be finally arranged, press-marked, and installed in a room adjacent to the King's Library, which is to be specially constructed to contain it in its original book- cases, which have been given by Mrs Wise."[6]

- "...a total of 206 leaves were stolen from the Museum's early quartos. Eighty-nine of these have been identified in Ashley copies and sixty in Wrenn copies; up to fifteen more may be added to this total from three suspect Wrenn copies... my personal opinion is that the plays are probably the only class where thefts were widespread."[10]

- "In general, it seems likely that Wise would not have risked sharing his guilty knowledge with an emissary but would have made the thefts himself; the rest of this study is written on that assumption."[12]

Citations

- "The Ashley Library". The Times. 11 September 1937. p. 14.

- "Mr. T. J. Wise Bibliographer, Editor, And Collector". The Times (47684). 14 May 1937. p. 17.

- "Forging a Collection; Thomas J. Wise and H. Buxton Forman, the Two Forgers". University of Delaware Library, Special Collections. 21 December 2010. Retrieved 2011-01-28.

- Maggs & Wise 1965.

- "The Ashley Library; Purchase For The Nation, The Late T. J. Wise And His Books". The Times. 11 September 1937. p. 11.

- Marsden, W. A. (January 1938), "The Ashley Library", The British Museum Quarterly, British Museum, 12.1: 20–21, JSTOR 4422035

- Named Collections of Printed Materials, British Library, archived from the original on 2011-01-24

- Jackson 2001.

- Burnett & Wise 1999.

- Foxon 1959, p. 1.

- "Harry Ransom Center, John Henry Wrenn Library". University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- Foxon 1959, p. 3.

Sources

- Burnett, T A J; Wise, Thomas James (1999), The British Library catalogue of the Ashley manuscripts, London: British Library, ISBN 978-0-7123-4572-9, British Library 006760053

- Foxon, David Fairweather (1959), "Thomas J. Wise and the pre-Restoration drama: a study in theft and sophistication", Transactions: Supplement, Bibliographical Society (Great Britain), 19, OCLC 1470724

- Jackson, Holbrook (2001) [1930], The anatomy of bibliomania (reprint ed.), Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, p. 450, ISBN 978-0-252-07043-3

- Maggs, Frank Benjamin; Wise, Thomas James (1965). The Delinquent Bibliophile: Thomas James Wise and the foundation of the Ashley Library. Radlett Literary Society. OCLC 24596991., British Library 2718.cc.62

Further reading

- Ratchford, F. E., Ed. (1973) [1939]. Letters of Thomas J. Wise to John Henry Wrenn (reprint ed.). W. G. Partington, Forging Ahead.[1]

- Wise, Thomas J. (1959). Centenary Studies.[1]

- "Wise, Thomas James". The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia (6th ed.). Columbia University Press, Infoplease. 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2015.