University of Delaware

The University of Delaware (colloquially UD or Delaware) is a private-public land-grant research university located in Newark, Delaware. UD is the largest university in Delaware. It offers 3 associate's programs, 148 bachelor's programs, 121 master's programs (with 13 joint degrees), and 55 doctoral programs across its eight colleges.[6] The main campus is in Newark, with satellite campuses in Dover, Wilmington, Lewes, and Georgetown. It is considered a large institution with approximately 18,200 undergraduate and 4,200 graduate students. It is a privately governed university which receives public funding for being a land-grant, sea-grant, and space-grant state-supported research institution.[7]

| |

| Latin: Universitas Delavariensis | |

| Motto | Scientia Sol Mentis Est (Latin) |

|---|---|

Motto in English | Knowledge is the light of the mind |

| Type | Private/Public land-grant research university |

| Established | 1833 (antecedent school founded 1743 and chartered 1769) |

Academic affiliations | Sea-grant Space-grant |

| Endowment | $1.466 billion (2019)[1] |

| President | Dennis Assanis |

Academic staff | 1,172 (2012)[2] |

Administrative staff | 4,004 |

| Students | 24,120 (Fall 2018)[3] |

| Undergraduates | 18,221 (Fall 2018)[3] |

| Postgraduates | 4,164 (Fall 2018)[3] |

Other students | 1,735 (Fall 2018)[3] |

| Location | , , United States |

| Campus | Suburban 2,012 acres (8.14 km2)[4] |

| Colors | Blue and gold[5] |

| Nickname | Fightin' Blue Hens |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division I FCS – CAA |

| Mascot | YoUDee |

| Website | www |

| |

UD is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity".[8] According to the National Science Foundation, UD spent $186 million on research and development in 2018, ranking it 119th in the nation.[9][10] It is recognized with the Community Engagement Classification by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.[11]

UD is one of only four schools in North America with a major in art conservation. In 1923, it was the first American university to offer a study-abroad program.[12]

UD traces its origins to a "Free School," founded in New London, Pennsylvania in 1743. The school moved to Newark, Delaware by 1765, becoming the Newark Academy. The academy trustees secured a charter for Newark College in 1833 and the academy became part of the college, which changed its name to Delaware College in 1843. While it is not considered one of the colonial colleges because it was not a chartered institution of higher education during the colonial era, its original class of ten students included George Read, Thomas McKean, and James Smith, all three of whom went on to sign the Declaration of Independence. Read also later signed the United States Constitution.

History

Early years: Newark Academy

The University of Delaware traces its origins to 1743, when Presbyterian minister Francis Alison opened a "Free School" in his home in New London, Pennsylvania.[13][14] During its early years, the school was run under the auspices of the Philadelphia Synod of the Presbyterian Church. The school changed its name and location several times. It moved to Newark by 1765 and received a charter from the colonial Penn government as the Academy of Newark in 1769. In 1781, the academy trustees petitioned the Delaware General Assembly to grant the academy the powers of a college, but no action was taken on this request.[15]

Transformation to Delaware College

In 1818, the Delaware legislature authorized the trustees of the Newark Academy to operate a lottery in order to raise funds with which to establish a college.[16] Commencement of the lottery, however, was delayed until 1825, in large part because some trustees, several of whom were Presbyterian ministers, objected to involvement with a lottery on moral grounds.

In 1832, the academy trustees selected the site for the college and entered into a contract for the erection of the college building. Construction of that building (now called Old College) began in late 1832 or in 1833. In January 1833 the academy trustees petitioned the Delaware legislature to incorporate the college and on February 5, 1833, the legislature incorporated Newark College, which was charged with instruction in languages, arts and sciences, and granted the power to confer degrees. All of the academy trustees became trustees of the college, and the college absorbed the academy, with Newark Academy becoming the preparatory department of Newark College.

Newark College commenced operations on May 8, 1834, with a collegiate department and an academic department, both of which were housed in Old College. In January 1835, the Delaware legislature passed legislation specifically authorizing the Newark Academy trustees to suspend operations and to allow the educational responsibilities of the academy to be performed by the academic department of Newark College. If, however, the college ever ceased to have an academic department, the trustees of the academy were required to revive the academy.[17]

In 1841 and 1842 separate classroom and dormitory buildings were constructed to teach and house academic department students. These buildings would later form the east and west wings of the Newark Academy Building located at Main and Academy Streets.

In 1843, the name of the college was changed to Delaware College.

The college was supported by a state authorized lottery until 1845. By the late 1840s, with the loss of lottery proceeds, the college faced serious financial problems. A scholarship program was adopted to increase enrollment and revenues. Although enrollment did increase to levels that would not be surpassed until the 1900s (there were 118 college students in 1854), the plan was fiscally unsound, and the financial condition of the school deteriorated further.[13] After a student fracas in 1858 resulted in the death of a student, the college suspended operations in 1859, although the academy continued to operate.

Land-Grant College

The Civil War delayed the reopening of the college. In 1867, college trustees lobbied the Delaware legislature for Delaware College to be designated as Delaware's land-grant college pursuant to the Morrill Land-Grant College Act.[18] Introduced by Congressman Justin S. Morrill of Vermont in 1857 and signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln in 1862, the Morrill Land-Grant College Act granted public lands to each state in order to establish schools to teach agriculture and engineering. On Jan. 12, 1869, the Board of Trustees of Delaware College signed an agreement to become the state's land-grant institution. In exchange, the state received a one-half interest in the property of the college and the authority to appoint half of the members of the Board of Trustees. The Morrill Land-Grant College Act granted Delaware the title to 90,000 acres in Montana which it sold and invested the profits into bonds used to fund the college.

Delaware College's new status as a semipublic college led to the termination of its official connection with the private academy. In 1869, the Newark Academy was revived as a separate institution operating under the 1769 charter.

In 1870, Delaware College reopened. It offered classical, scientific and, as required by its land-grant status, agricultural courses of study. In an effort to boost enrollment, women were admitted to the college between 1872 and 1885.

In 1887, Congress passed the Hatch Act, which provided Delaware College with funding with which to establish an agricultural experiment station. In 1890, the college purchased nine acres of land for an experimental farm located next to its campus. In 1890 the college became the recipient of more federal aid when the New Morrill Act was passed. It provided for annual payments to support land-grant colleges. Under the law, the State of Delaware initially received $15,000 per year, which was to be increased by $1,000 per year until it reached $25,000. Delaware College received 80% of this money. (It did not receive all of it because the law provided that in states in which land-grant colleges did not admit black students, an equitable amount of the granted money had to be used to educate the excluded students. Delaware College had never admitted black students (although it had admitted Native American and Asian students), and as a result the state of Delaware established Delaware State College near Dover for black students, which opened in 1892.) In 1891 and 1893 Delaware College received appropriations from the State of Delaware for the construction of new buildings. One new building built with this money was Recitation Hall.

As a result of this additional funding, Delaware College was invigorated. New buildings, improved facilities, and additional professors helped the college attract more students. Student life also became more active during this period. In 1889 the first football game involving a team representing the college was played. Also in 1889, the college adopted blue and gold as the school's colors.

It was not until 1914, though, that the Women's College opened on an adjoining campus, offering women degrees in Home Economics, Education, and Arts and Sciences. Brick archways at Memorial Hall separated the Men's and Women's campuses and gave rise to the legend of the Kissing Arches (where students would kiss good night before returning to their respective residence halls).

In 1921, Delaware College was renamed the University of Delaware, and it officially became a coeducational institution in 1945 when it merged with the Women's College of Delaware.[19]

The university grew rapidly during the latter half of the 20th century. After World War II, UD enrollment skyrocketed, thanks to the G.I. Bill. In the late 1940s, almost two-thirds of the students were veterans. Since the 1950s, UD has quadrupled its enrollment and greatly expanded its faculty, its academic programs and its research enterprise.

In 2010–11, the university conducted a feasibility study in support of plans to add a law school focused on corporate and patent law.[20] At its completion, the study suggested that the planned addition was not within the university's funding capability given the nation's economic climate at the time.[20] Capital expenses were projected at $100 million, and the operating deficit in the first ten years would be $165 million. The study assumed an initial class of two hundred students entering in the fall of 2015.[20] Widener University has Delaware's only law school.[20]

Science, Technology and Advanced Research (STAR) Campus

On October 23, 2009, the University of Delaware signed an agreement with Chrysler to purchase a shuttered vehicle assembly plant adjacent to the university for $24.25 million as part of Chrysler's bankruptcy restructuring plan.[21] The university has developed the 272-acre (1.10 km2) site into the Science, Technology and Advanced Research (STAR) Campus. The site is the new home of UD's College of Health Sciences, which includes teaching and research laboratories and several public health clinics. The STAR Campus also includes research facilities for UD's vehicle-to-grid technology, as well as Delaware Technology Park, SevOne, CareNow, Independent Prosthetics and Orthotics, and the East Coast headquarters of Bloom Energy.[22] In 2020, UD expects to open the Ammon Pinozzotto Biopharmaceutical Innovation Center, which will become the new home of the UD-led National Institute for Innovation in Manufacturing Biopharmaceuticals. Also, Chemours recently opened its global research and development facility, known as the Discovery Hub, on the STAR Campus in 2020. The new Newark Regional Transportation Center on the STAR Campus will serve passengers of Amtrak and regional rail.

Academics

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| ARWU[23] | 66–94 |

| Forbes[24] | 147 |

| THE/WSJ[25] | 148 |

| U.S. News & World Report[26] | 97 |

| Washington Monthly[27] | 94 |

| Global | |

| ARWU[28] | 201–300 |

| QS[29] | 491 |

| THE[30] | 301–350 |

| U.S. News & World Report[31] | 311 |

|

USNWR graduate school rankings[32] | |

|---|---|

| Business | 99-131 |

| Education | 45 |

| Engineering | 47 |

|

USNWR departmental rankings[32] | |

|---|---|

| Biological Sciences | 140 |

| Chemistry | 59 |

| Clinical Psychology | 36 |

| Computer Science | 68 |

| Criminology | 15 |

| Earth Sciences | 78 |

| Engineering | 58 |

| English | 77 |

| Fine Arts | 157 |

| History | 91 |

| Mathematics | 74 |

| Physical Therapy | 1 |

| Physics | 71 |

| Political Science | 81 |

| Psychology | 66 |

| Public Affairs | 39 |

| Sociology | 63 |

The university is organized into eight colleges:

- Alfred Lerner College of Business and Economics

- College of Agriculture and Natural Resources

- College of Arts and Sciences

- College of Earth, Ocean and Environment

- College of Education and Human Development

- College of Engineering

- College of Health Sciences

- Graduate College

- Honors College

There are also five schools:

- Joseph R. Biden, Jr. School of Public Policy and Administration (part of the College of Arts & Sciences)[33]

- School of Education (part of the College of Education & Human Development)

- School of Marine Science and Policy (part of the College of Earth, Ocean and Environment)

- School of Nursing (part of the College of Health Sciences)

- School of Music (part of the College of Arts & Sciences)

Rankings

U.S. News & World Report ranked UD's undergraduate program tied for 97th among "national universities" and tied for 39th among public universities in 2021.[34]

Times Higher Education World University Rankings ranked UD 148th nationally and between 300 and 350 internationally in 2020.[35]

Alfred Lerner College of Business and Economics

The Alfred Lerner College of Business and Economics offers bachelor's, master's and doctoral degree programs across five departments: accounting and MIS, business administration, economics, finance and hospitality business management.

As the second largest of UD's eight colleges, Lerner includes a diverse community of 3,332 undergraduate students, 869 graduate students, 209 faculty and staff, and more than 34,000 alumni across the globe. Lerner is the only Delaware business school with a dual AACSB-accreditation in business (1966) and accounting (1984).

Lerner maintains its own Career Services center and undergraduate advising department and houses two research centers, the Center for Economic Education and Entrepreneurship (CEEE) and the Institute for Financial Services Analytics (IFSA). Its experiential learning facilities include the Geltzeiler Trading Center, Vita Nova restaurant, and the Courtyard Newark at the University of Delaware, owned by UD and managed by Shaner Hotels.

The college became the Alfred Lerner College of Business and Economics in 2002. It was named after MBNA chairman and CEO Alfred Lerner, who was one of America's successful business leaders and philanthropists, especially in his support of educational causes.

In Fall 2014, University of Delaware created a Ph.D. in Financial Services Analytics (FSAN). The Ph.D. in FSAN is a cross-disciplinary program offered by the Alfred Lerner College of Business and Economics and the College of Engineering at the University of Delaware, and was funded in part by a grant from JPMorgan Chase. The program is the first of its kind.

The School of Business and Economics was created in 1963, and was formally founded as of the College of Business and Economics in 1965.

The first MBA program at UD began in 1952. In 1917 the University of Delaware established the first undergraduate business major in business administration.

College of Agriculture and Natural Resources

The College of Agriculture and Natural Resources offers bachelor's, master's and doctoral degree programs across four departments: animal and food sciences, entomology and wildlife ecology, plant and soil sciences, and applied economics and statistics. As of fall 2018, the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources had 81 faculty, 851 undergraduate students and 205 graduate students.

One of the few colleges in the country with a working farm on campus, the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources includes a 350-acre outdoor classroom in Newark that includes a working dairy farm, equine barns, statistics and experimental economics labs, botanic gardens, greenhouses, ecology woods, an apiary, farmland, forests, grasslands, wetlands, and a working creamery. [36]

In Georgetown, Del., the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources is home to the Carvel Research and Education Center, which includes more than 300 acres of farmland for agronomy research and varietal trials. The Lasher Laboratory, also on the Georgetown campus, is the primary poultry diagnostic laboratory in the state of Delaware, providing diagnostic services to commercial poultry producers and owners of small non-commercial flocks.

University of Delaware's Cooperative Extension, the outreach arm of the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources established by the Smith-Lever Act in 1914, completes the tripartite mission of land-grant institutions to offer teaching, research and service. Cooperative Extension takes the innovative work developed at the college and shares it with the public, putting knowledge into practice in pursuit of economic vitality, ecological sustainability and social wellbeing.

College of Arts and Sciences

Through the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Delaware students can choose from an array of concentrations. They can choose from programs in visual and performing arts, social sciences, natural sciences and many more.[37] The College of Arts and Sciences has 23 academic departments. It is the largest of UD's colleges, with about 6,400 undergraduate students, 1,200 graduate students and more than 600 faculty members.[38]

The Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences is John A. Pelesko, who has been a UD faculty member in the Department of Mathematical Sciences since 2002. Pelesko previously served as associate dean for the natural sciences of the College of Arts and Sciences from 2016 to 2018.

College of Earth, Ocean and Environment

The College of Earth, Ocean and Environment (CEOE) is made up of the Department of Geography and Spatial Sciences, the Department of Earth Sciences, and the School of Marine Science and Policy. There are four programs in the School of Marine Science and Policy: Marine Biosciences, Oceanography, Physical Ocean Science and Engineering, and Marine Policy. The college offers over nine undergraduate majors, and 17 graduate degrees and two professional certificates.

Undergraduate science majors at UD have the opportunity to apply for the CEOE's Semester-in-Residence Program, in which students live and work at the Lewes campus which is located on the Delaware Bay. The Lewes campus has many advanced marine research facilities, including the Global Visualization Lab and the Robotic Discovery Laboratories, both of which focus on the use of autonomous research vehicles for collecting data underwater, from the surface and in the air. Lewes is also home to UD's marine operations, which feature the R/V Joanne Daiber for research in the Delaware Bay and the R/V Hugh R. Sharp, a 146-foot, state-of-the-art coastal research vessel that operates as a member of the University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System (UNOLS). Students work on a research project guided by a faculty member in addition to taking "introductory graduate-level classes." Additionally, any student in the United States who is enrolled in a bachelor's degree program may apply for the college's Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) program.

In 2019, CEOE opened the Offshore Wind Skills Academy, the first US skills training program for offshore wind energy professionals.

The college also offers may undergraduate study abroad opportunities to places such as New Zealand, Mexico, Bonaire, Fiji, Barbados, Austria, and London. A geology fieldwork course held in various locations throughout the American West is also available and required for geological sciences majors.

College of Engineering

The U.S. News & World Report ranked the University of Delaware's engineering graduate program as #47[39] and the undergraduate program as #55 in 2018.[40] U.S. News & World Report ranked both the undergraduate and graduate chemical engineering programs as #9 in the country in 2018.

The College of Engineering is home to seven academic departments offering bachelor's degree, master's degree and doctoral degree programs focused on challenges associated biopharmaceuticals, cybersecurity, data science, energy, the environment, human health, infrastructure, manufacturing, materials and nanofabrication. Undergraduate degrees are offered in biomedical engineering, chemical engineering, civil engineering, computer engineering, computer science, construction engineering and management, electrical engineering, environmental engineering, information systems, materials science and engineering, and mechanical engineering. As of fall 2018, the College of Engineering had 180 full-time faculty, 2,425 undergraduate students and 932 graduate students.

The faculty includes 31 named professors, eight career development named professors, eight National Academy of Engineers members, 44 NSF career award winners and 17 University teaching award recipients. Initiatives led by college faculty include 15 college-based research centers and 14 university-based research institutes.

The College of Engineering has a presence in approximately 20 different buildings on and off campus. This includes modern classrooms and research laboratories such as the Advanced Materials Characterization Lab and Nanofabrication Facility located in the Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering Laboratory.

College of Health Sciences

The College of Health Sciences (CHS) is home to seven academic departments, including newly created Epidemiology. The College of Health Sciences offers bachelor's degree, master's degree and doctoral degree programs that take evidence-based research and translate it into person-centered care. Undergraduate degrees are offered in applied molecular biology and biotechnology, exercise science, health behavioral science, medical diagnostics, medical laboratory science, nursing, nutrition, nutrition and dietetics, nutrition and medical sciences, and sports health. Pre-physician's assistant and occupational therapy tracks are also available. As of fall 2018, the College of Health Sciences included 148 faculty, 2,556 undergraduate students and 509 graduate students. The College includes the state of Delaware's only education program for speech pathologists, a state-of-the-art Health Design Innovation space to bring research to life and change the quality-of-life for the surrounding community.

U.S. News & World Report ranked the University of Delaware's physical therapy program as #1 in 2016. The College of Health Sciences was ranked #2 in National Institute of Health funding among Schools of Allied Health Professions in 2018.

The college is headquartered at the university's Science, Technology and Advanced Research (STAR) Campus. Located on the site of a former Chrysler automotive assembly plant, College of Health Sciences buildings include the Health Sciences Complex (opened in December 2013) and the Tower at STAR (opened in August 2018). The Health Sciences Complex includes Translation Hallway; where research labs translate into clinical care across the hallway. The Tower at STAR includes a Demonstration Kitchen, Living Wall, Exercise Intervention Space for chronic disease, Health Design Innovation lab, Interprofessional Simulation space and a Simulation Apartment where prevention and wellness are the focus for the future of health care delivery. Plans for the STAR Campus include expanding university-based research and shared research in collaboration with the National Institute for Innovation in Manufacturing Biopharmaceuticals (NIIMBL) and the chemical company Chemours.

The college is also home to UD Health which includes three public clinics focusing on physical therapy, nurse managed primary care, and speech-language-hearing. Additional services include health coaching, nutrition counseling, and exercise testing/counseling. Recruitment is ongoing for many research studies as well.

Graduate College

On July 1, 2019, the University of Delaware transitioned the former Office of Graduate and Professional Education to the institution's eighth college.

The first doctoral programs at UD — in chemical engineering and chemistry — were approved in 1946. The University awarded its first doctorate — in chemical engineering — in 1948. Currently, more than 3,600 graduate students are enrolled at UD. The University offers more than 200 graduate and professional degree programs — many ranked by the National Research Council at the top of their fields.[41]

While the majority of graduate degrees are housed within the other seven colleges, the Graduate College serves as a coordinating body, providing administrative oversight for graduate student recruitment, student-life services, professional development programming, interdisciplinary programs, and marketing and market research.

Institute of Energy Conversion

The Institute of Energy Conversion (IEC) at the University of Delaware is the oldest solar energy research institute in the world. It was established by Karl Boer in 1972 to pioneer research on thin film solar cells and today is one of the only laboratories in the world with expertise in Si, CdTe, and CuInSe2 based solar cells. This included the development of one of the first solar powered homes, a structure still utilized by the university's student-run ambulance service, the University of Delaware Emergency Care Unit.[42] Recently the IEC was the number one recipient of the DOE Sunshot Initiative and was awarded 5 grants totaling $9.1 million to research next generation solar cells to reduce the cost of solar cells by 75% by the end of the decade.[43]

Disaster Research Center

The Disaster Research Center, or DRC, was the first social science research center in the world devoted to the study of disasters. It was established at Ohio State University in 1963 and moved to the University of Delaware in 1985. The center conducts field and survey research on group, organizational and community preparation for, response to, and recovery from natural and technological disasters and other community-wide crises. DRC researchers have carried out systematic studies on a broad range of disaster types, including hurricanes, floods, earthquakes, tornadoes, hazardous chemical incidents, and plane crashes. DRC has also done research on civil disturbances and riots, including the 1992 Los Angeles unrest. Staff have conducted nearly 700 field studies since the center's inception, traveling to communities throughout the United States and internationally, including Mexico, Canada, Japan, Italy, and Turkey. Core faculty members are from the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice, the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, and the School of Public Policy and Administration. The staff also includes postdoctoral fellows, graduate students, undergraduates and research support personnel.

Delaware Biotechnology Institute

The Delaware Biotechnology Institute, or DBI, was organized as an academic unit of the University of Delaware in 1999 and moved into dedicated research facilities in 2001. DBI supports a statewide partnership of higher education, industry, medical, and government communities committed to the discovery and application of interdisciplinary knowledge in biotechnology and the life sciences. With some 180 people resident in the DBI facilities, including 20–25 faculty members representing 12 departments, 140 graduate and post-graduate students, and 20 professional staff members, DBI emphasizes a multi-disciplinary approach to life-science research. The core research areas pursued by DBI-affiliated faculty include agriculture, human health, marine environmental genomics, biomaterials, and computational biology/bioinformatics. Research in these and other areas is done in collaboration with faculty at Delaware State University, Delaware Technical and Community College, Wesley College, Christiana Hospital, and Nemours Hospital for Children. One of the primary objectives of the institute is to provide state-of-the-art research equipment to facilitate life science research and six core instrumentation centers and specialized facilities, each under the direction of an experienced researcher or administrator, is supported at DBI and made available to university researchers.

Delaware Environmental Institute

The Delaware Environmental Institute (DENIN) launched on October 23, 2009. DENIN is charged with conducting research and promoting and coordinating knowledge partnerships that integrate environmental science, engineering and policy.[44]

University of Delaware Energy Institute

The University of Delaware Energy Institute (UDEI) was inaugurated September 19, 2008. UDEI has been selected to receive a $3 million a year grant for advanced solar research.[45]

John L. Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance

The John L. Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance was established in 2000 at the Alfred Lerner College of Business and Economics. Its aim is to propose changes in corporate structure and management through education and interaction. The Center provides a forum for those interested in corporate governance issues.[46]

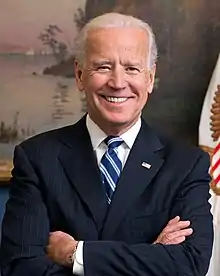

Joseph R. Biden, Jr. Institute

In February 2017, the School of Public Policy and Administration announced the creation of the Joseph R. Biden, Jr. Institute (Biden Institute), named after alumnus Joe Biden, the 46th and current President of the United States, who at the time had recently finished his term as the 47th Vice President.[47]

Students and admissions

| University of Delaware Admissions Statistics (2018)[48] | |

|---|---|

| Applicants | 26,491 |

| Acceptance Rate | 35% out of state, 53% (DE) |

| First Year Students | 1,377 (DE), 2,872 out of state |

| High School GPA Average | 3.8 |

| SAT Average, ACT | 1275, 27–31 |

| Freshman Class Size | 4161 |

| Number of Study Abroad Locations | 35+ |

| Undergraduate Colleges | 7 |

| Academic Offerings | 150+ majors, 76+ minors |

| Undergraduate Student-Faculty Ratio | 12:1 |

The student body at the University of Delaware is primarily an undergraduate population. The university offers more than 150 undergraduate degree programs and, due to the number of academic options, many students complete dual degrees as well as double majors and minors. UD students have access to work and internship opportunities, worldwide study abroad programs, research and service learning programs.

Campus

The campus itself is divided into four areas:[49]

- Main Campus, which has most of the academic and residential buildings, is centered on a roughly north–south axis between South College Avenue and Academy Street. At the center of the campus is Memorial Hall, which once divided the Women's College from Delaware College. North and south of Memorial Hall is a large, roughly rectangular green space known either as "The Green" or "The Mall," around which are many of the oldest buildings on campus. Though the buildings were constructed at various times over the course of more than a century, they follow a cohesive Georgian design aesthetic. The Green area is further subdivided into three areas. "North Central," which is north of Delaware Avenue, contains the original men's dormitories (now co-educational) of what was then Delaware College, as well as several classroom buildings north of Main Street in what had been the original Engineering departments. "Central," which lies between Delaware Avenue and Memorial Hall, contains many large classroom buildings and laboratories. "South Central," which extends from Memorial Hall to Park Place, houses the original Women's dormitories, as well as some classroom buildings and the Morris Library. Other areas around the Main Campus include "Harrington Beach," a large grassy quadrangle on the east side of main campus that serves as a common meeting and recreation place for students, and is surrounded by three large dormitory complexes and the Perkins Student Center. Several more classroom and laboratory buildings line the streets on either side of The Green, and there exists an area of closed dormitories (the former Dickinson and Rodney dormitory complexes) that lie at the outer edge of Main Campus across South Main Street.

- Laird Campus, which has several dormitories as well as a conference center, hotel, and the Christiana Towers apartment complex, lies north of Cleveland Avenue between New London Road and North College Avenue. The Christiana Towers are slated for demolition in 2021 or 2022 due to their age and expensive maintenance issues.

- South Campus has the agricultural school, all of the sports stadiums (including Delaware Stadium and the Bob Carpenter Center), and the Science, Technology and Advanced Research (STAR) Campus, which is built on the site of a former vehicle assembly plant. It lies south of the Northeast rail corridor and north of Christina Parkway (Delaware Route 4)

- The Delaware Technology Park, which lies to the far east of Main Campus, is designated north of the train tracks and south of Wyoming Road on either side of Library Avenue (Delaware Route 72) and has several research laboratories, classroom buildings, and offices. The Children's Campus, located across the street from the Delaware Technology Park, is a 15-acre site home to the Early Learning Center (ages 6 weeks to third grade), the Lab School (ages 6 months to kindergarten) and The College School (first to eighth grades). Also located on-site are UD's Cooperative Extension Master Gardeners Program and the Center for Disabilities Studies.

In 1891, prominent Philadelphia architect Frank Furness designed Recitation Hall.[50] Several buildings (Wolf, Sussex, and Harter Halls) were designed by Frank Miles Day, who also designed the formal campus landscape. From 1918 to 1952, Marian Cruger Coffin was appointed the university's landscape architect, a position which required her to unite the university's two separate campuses (the men's to the north and the women's to the south) into one cohesive design.[51] This was a challenge since the linear mall design of each was out of alignment with the other. Coffin solved this problem by linking them with a circle (now called Magnolia Circle) instead of curving the straight paths, which rendered the misalignment unnoticeable to the pedestrian.[52]

North, or Laird, Campus, is primarily residential. It is the former home to the Pencader Complex, which was demolished and replaced by three new residence halls. A total of four residence hall buildings have been built, three named after the three University alumni who signed the Declaration of Independence (George Read, Thomas McKean, and James Smith, who signed for Pennsylvania); the fourth residence hall was named Independence Hall.[53] The Christiana Towers, an apartment-style residence complex, was closed in 2019, and is slated for demolition. In addition, the construction of a Marriott Courtyard run by the HRIM (Hotel Restaurant and Institutional Management) department expanded the campus.

Other major facilities that have opened since 2000 include:

- The David and Louise Roselle Center For The Arts, with facilities for the school's music and theater programs, was opened in 2006. It is named for the university's 25th president and his wife.

- In 2013, two new residence halls, named after former college president Eliphalet Gilbert and Delaware Civil Rights pioneer Louis L. Redding, were opened on the East Campus housing complex.[54]

- Also in 2013, the Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering (ISE) Laboratory opened on the corner of Academy and Lovett streets. In 2015, it was named the Patrick T. Harker ISE Laboratory in honor of the university's 26th president.

- The Caesar Rodney Residence and Dining Hall opened in fall 2015 on Academy Street across from Perkins Student Center.

- The South Academy Residence Hall opened in fall 2017 next to Caesar Rodney Residence Hall.

- The Tower at STAR opened on the STAR Campus in 2018.

Administration

In 2015, the UD Board of Trustees elected Dennis Assanis as the 28th President of the University of Delaware; he took office in June 2016. He succeeded Nancy Targett, former Dean of the University's College of Earth, Ocean and Environment, who served as interim president in 2015–16. She was named 27th president of the university near the end of her service; she was the institution's first female president. Targett served after the departure of President Patrick Harker in 2015 to serve as the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.[55]

Funding

The university receives funding from a variety of sources as a consequence of its historical origins. Among those sources is the State of Delaware budget. In fiscal year 2018, the state operating appropriation was 12% of the university's operating revenue.[56] Tuition and fees (net of scholarships and fellowships) make up 43% of the university's operating budget.

The Delaware First fundraising and engagement campaign is the largest philanthropic campaign in UD history. Launched in November 2017, the campaign goal is to raise $750 million by summer 2020. As of spring 2019, the campaign had raised about $700 million.

Study abroad

The University of Delaware was the first American university to begin a study-abroad program, which was later adopted by many other institutions.[57] The program began when Professor Raymond Watson Kirkbride took a group of eight students to Paris, France, during the fall semester of 1923. Since this initial trip, the University of Delaware has expanded its study-abroad program, which now encompasses more than 40 countries. About one-third of UD undergraduate students take advantage of study-abroad experiences prior to completing their bachelor's degrees.

Delaware's study-abroad program offers many options for students. Undergraduates have the option of studying abroad for a five-week winter or summer session, or an entire semester.[58]

Athletics

The athletic teams at Delaware are known as the Fightin' Blue Hens with a mascot named YoUDee. YoUDee is a Blue Hen Chicken, after the team names and the state bird of Delaware. YoUDee was elected into the mascot hall of fame in 2006, and is an eight-time UCA Open Division Mascot National Champion.[59]

UD offers 21 varsity sports, which compete in the NCAA Division-I (FCS for football). Delaware is a member of the Colonial Athletic Association (CAA) in all sports. Delaware was a member of the Atlantic 10 Conference in football until the 2006 season. The Fightin' Blue Hens football teams have won six national titles, including the 2003 NCAA I-AA Championship. In 2007, the Delaware Blue Hens were the runners up in the NCAA I-AA National Championship game, but were defeated by defending champions Appalachian State. In 2010, the Delaware Blue Hens were again runners up in the National Championship game, losing to Eastern Washington 20–19 after being up 19–0 earlier in the game.

Former head football coaches Bill Murray, Dave Nelson and Harold "Tubby" Raymond are College Football Hall of Fame inductees. Delaware is one of only two schools to have three straight head coaches inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame (Georgia Tech is the other).[60]

Delaware's only other NCAA National Championships came in 1983 for Women's Division I Lacrosse[61] and in 2016, when the Delaware women's field hockey team won the school's first NCAA Division I national championship, defeating North Carolina, 3–2.

The Blue Hens have won 26 CAA Championships since joining in 2001:

| Team | Number | Years |

|---|---|---|

| women's field hockey | 6 | 2004, 2009, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016 |

| men's soccer | 5 | 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016 |

| women's volleyball | 4 | 2007, 2008, 2010, 2011 |

| women's basketball | 3 | 2005, 2012, 2013 |

| men's lacrosse team | 3 | 2007, 2010, 2011 |

| women's track and field | 2 | 2014, 2019 |

| women's golf | 1 | 2015 |

| men's basketball team | 1 | 2014 |

| football | 1 | 2010 (co-champs with William & Mary) |

Unofficially, the women's rowing team has won the CAA title four times since 2001, placing second the other two times. The 2007 men's lacrosse program reached the final four of the NCAA Tournament for the first time in its history.

On March 7, 2012, the Division 1 men's ice hockey team won the ACHA National Championship. UD defeated Oakland University 5–1, capturing its first title.

"The Delaware Fight Song" first appeared in the Student Handbook in 1933.[62] It was composed by alumnus George F. Kelly (Class of 1915).

Intrastate competition

In November 2007, it was announced that the University of Delaware and Delaware State University would have their first game against each other, the game being in the first round of the NCAA Division I Football Championship Subdivision playoffs. The game was played on November 23, with University of Delaware winning 44–7.[63] Delaware has won all of the regular season match-ups, which have been called the Route 1 Rivalry. In all, the two schools played eight games between 2007 and 2017. Games are scheduled for 2019 and 2020. In 2019, UD and DSU announced that they have scheduled six games against each other from 2024 through 2030, including the first two games at DSU's Alumni Stadium.[64]

Music

The University of Delaware has a variety of musical performance opportunities available to students, including a wind ensemble, orchestra, symphonic band. There are also a number of jazz groups available, including two large ensembles, and a smaller group that focus on improvisation. All ensembles are open by audition to all students at the university, and can be taken either for credit or for no credit. The school also has a steel drum ensemble, and an early music ensemble. There are also a variety of choral ensembles, including the University of Delaware Chorale, an all-women's choir, and three choirs, also open to community members, that constitute the Schola Cantorum. The music department's home is the Amy E. du Pont Music Building, named for Amy Elizabeth du Pont, a prominent benefactor of the university during the 20th century.

In addition, the University of Delaware is known for having one of the best marching bands on the east coast, the University of Delaware Fightin' Blue Hen Marching Band. The band ranges from 300 to 350 members every year and can be seen performing at every home football game as well as at various festivals and competitions, including the Collegiate Marching Band Festival in Allentown. Additionally, the marching band was selected to perform in the 56th Presidential Inaugural Parade in 2009.[65]

In 2006, the new Center for the Arts building opened. This building has a number of recital halls and a large number of practice rooms, most with upright pianos. The practice rooms are locked and cannot be used by students who are not music majors or in an official UD ensemble. The university employs a tiered access system, with larger rooms and rooms with grand pianos being reserved for certain groups of students. In addition the music department also uses their old building, with offices, classrooms, practice rooms, and recital halls. This building has public-access practice rooms with pianos.

In 2005, the University of Delaware Chorale, under the direction of Paul D. Head and accompanied by Betsy Kent, were invited to perform at the American Choral Directors Association's International Convention in Los Angeles. In April 2007, the Chorale won the Grand Prix at the Tallinn International Choral Festival in Estonia, having scored higher than 40 other choirs from around the world. In 2010 the Chorale competed in two categories of the 42nd Annual Tolosa Choral Competition in Tolosa, Spain; They received a Bronze and a Silver award. UD-16, a chamber ensemble of Chorale also competed in Tolosa in two categories and won two Silver awards. In the Summer of 2012 the Chorale was the only American College Choir to be invited to the International Society for Music Education Conference in Thessaloniki, Greece; the UD Steele Ensemble was also invited. On that same tour, the chorale placed in a close 2nd at the Grand Prix of the 25th Bela Bartok International Choral Competition. In 2000, the music department purchased an 18th-century Ceruti violin for professor and violinist Xiang Gao.

In December 2019, the Department of Music in the College of Arts and Sciences was officially renamed the School of Music.

The university also has a student run radio station, 91.3 WVUD, as well as several a cappella groups including one all-female, one all-male, and five mixed groups, several of which compete regularly at the International Championship of Collegiate A Cappella (ICCA). The most successful group is Vocal Point, who placed 3rd at ICCA finals in 2014. In 2020, The A Cappella Archive ranked UD Vocal Point at #12 all-time among ICCA-competing groups.[66]

Student life

Tuition

For the 2019–20 academic year, undergraduate tuition and fees is $14,280 for Delaware residents and $35,710 for non-residents. Total cost of attendance for the 2019–20 academic year (tuition, mandatory fees, room and board) is $27,488 for Delawareans and $48,918 for non-residents.[67]

Media

There are currently two student publications at Delaware: The Review and UDress, as well as radio and television stations.

Print

The Review is a weekly student publication, released in print and online on Tuesdays. It is an independent publication and receives no financial support from the university. It is distributed at several locations across campus, including Morris Library, the Perkins Student Center and the Trabant University Center, as well as various academic buildings and the dining halls. The Review's office is located at 250 Perkins Student Center, facing Academy Street, and is above the offices of WVUD. In 2004, it was a National Newspaper Pacemaker Award Finalist, and was also named one of the ten best non-daily college newspapers by the Associated Collegiate Press.[68] It currently has a print circulation of 10,000.

UDress magazine is the on-campus fashion magazine which publishes one issue per semester, in conjunction with fashion events.

Broadcast

The student-run, non-commercial, educational radio station at Delaware broadcasts on 91.3 and uses the call letters WVUD, which the university purchased from the University of Dayton in the 1980s. Although not its intended call letter pronunciation, 'VUD has taken on the slogan "the Voice of the University of Delaware." They are licensed by the city of Newark, Delaware and broadcasts with a power of 1,000 watts 24 hours a day with its offices and studios located in the Perkins Student Center.[69]

The transmitting facilities are located atop the Christiana East Tower residence hall. WVUD is operated by University of Delaware students, a University staff of two, and community members. No prior radio experience is necessary, nor is there a need to enroll in any certain major to become a part of WVUD. The radio station has a variety of programming, featuring both music and talk formats.

STN is the student-run, non-commercial, educational television station at the University of Delaware. The station broadcasts second-run movies, original student produced content as well as live sports coverage. The initials, STN, originally stood for Shane Thomas Network, later changed to Student Television Network.[70]

Greek life

Approximately 25% of the University of Delaware's undergraduate student population is affiliated with a fraternity or sorority.[71] There are over 26 fraternities and 20 sororities (chapters & colonies) in the Interfraternity Council (IFC), National Panhellenic Conference (NPC), and Multicultural Greek Congress (MGC). They all coordinate via the Greek Council. All Greek organizations participate in an accreditation process called the Chapter Assessment Program (CAP).[72] CAP ratings award chapters with either a Gold, Silver, Bronze, Satisfactory or Needs Improvement designation. This system is an expansion from the Five Star program of the late 1990s, requiring contributions to community service, philanthropy, university events, diversity education, professional education, a chapter/colony GPA greater than or equal to the all men's or all women's average, and attendance and compliance with numerous other criteria.

Active fraternities include Alpha Phi Alpha, Kappa Alpha Psi, Phi Kappa Tau, Phi Beta Sigma, Lambda Sigma Upsilon, Pi Alpha Phi, Phi Kappa Psi, Delta Tau Delta, Delta Sigma Pi, Alpha Sigma Phi, Kappa Delta Rho, Kappa Sigma, Sigma Alpha Epsilon, Alpha Gamma Rho, Lambda Chi Alpha, Sigma Pi, Sigma Phi Delta, Theta Chi, Kappa Alpha Order, Pi Kappa Phi, Zeta Beta Tau, Sigma Nu, Phi Gamma Delta, and Sigma Phi Epsilon.

Active sororities include Delta Sigma Theta, Alpha Kappa Alpha, Zeta Phi Beta, Lambda Theta Alpha, Chi Upsilon Sigma, Lambda Pi Chi, Delta Phi Lambda, Phi Sigma Sigma, Alpha Delta Pi, Alpha Xi Delta, Gamma Phi Beta, Alpha Epsilon Phi, Chi Omega, Sigma Kappa, Alpha Phi, Delta Gamma, Alpha Sigma Alpha, Pi Beta Phi, Delta Delta Delta, and Kappa Alpha Theta.

Alcohol abuse

A campus website claims that a 1993 study by the Harvard School of Public Health found that high-risk drinking at UD exceeded the national norm. On this survey, a majority of students reported binge drinking more than once in a two-week interval. The average consumption for students was nine drinks per week, while 29% reported that they drink on 10 or more occasions per month. UD students were found to be more aware of policies, prevention programs, and enforcement risks than the national average.[73]

In 2005, on the Newark campus of the university 1140 students were picked up by the campus police for alcohol-related violations. Of these, 120 led to arrests. These figures are up from previous years, 1062 in 2004 and 1026 in 2003.[74] This represents approximately 6% of the student population.[75]

At least one student organization has undertaken the goal of "providing fun activities for those who chose not to drink" and to "promote the idea that one doesn't need alcohol to have a good time."[76]

In 2008, a University of Delaware freshman died of alcohol poisoning after attending a party hosted by members of the Sigma Alpha Mu fraternity, where the student was pledging.[77]

Although the university has attempted to make efforts in preventing alcohol abuse, a student visiting from another college died on March 19, 2016 in an alcohol-related incident.[78] The student was standing alone on the roof of an off-campus fraternity, and slipped off it.

Shuttle service

The University of Delaware operates multiple shuttle routes called "UD Shuttle" that serve the campus. The North/South Academy route runs the north–south length of the campus via Academy Street and offers daily service, with late night service Friday and Saturday. The North/South College route runs the north–south length of the campus via College Avenue and offers service on weekdays. The East Loop route runs a loop through the eastern part of the campus and Newark and offers daily service, with late night service Friday and Saturday. The West Loop route runs a loop through the western part of the campus and Newark and offers daily service, with late night service Friday and Saturday. The Early Bird route offers early morning weekday service serving the north–south length of the campus while the Late Bird route offers late night service daily serving the north–south length of the campus.[79]

Health

The University of Delaware Emergency Care Unit (UDECU) is a registered student organization at the university, which provides emergency medical services to the campus and surrounding community. UDECU has approximately 50 members, all of which are volunteers and students at the University of Delaware. UDECU operates one basic life support ambulance (UD-1), one first response vehicle (UD-2), and a bike team.[80][81] Advanced life support is provided by New Castle County Emergency Medical Services.

Controversies

Power plant

The university agreed to lease 43 acres on the STAR campus to The Data Centers (TDC) for the construction of the data center. The data center plan included a combined heat cycle natural gas-fired power plant capable of generating 248 megawatts of power.[82] TDC claimed that the power plant was critical to ensuring an uninterrupted electrical power supply to the facility, which is critical for data integrity. The TDC business plan also called for sale of excess electricity. Portions of the Newark community questioned the business plan, claiming that the power plant is not an auxiliary part of the data center but a separate industrial use, which would violate the zoning of the STAR campus.[83]

On April 28, 2014, the City of Newark Board of Adjustment upheld its April 19, 2014 ruling that the power plant is an accessory to the data center and that no rezoning was required.[84] The ruling is presently under appeal. The University of Delaware's Sustainability Task Force sent an open letter to President Harker citing concerns that the project violates the university's strategic plan and Climate Action Plan.[85] On May 4, 2014, the University Faculty Senate voted 43 to 0 (with 8 abstentions) to recommend to the administration that it not allow construction of The Data Center on UD's STAR campus if The Data Center includes any fossil-fuel-burning power plant.[86][87] On July 10, 2014 the university announced that it was terminating the lease for the project.[88]

Orientation

In the fall of 2007, the university implemented a new residence-life education program that was criticized for forcing students into polarizing discussions. The program was abandoned in November of the same year.[89]

Notable alumni and faculty

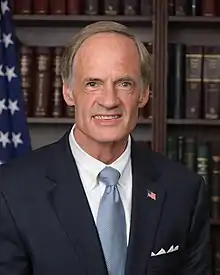

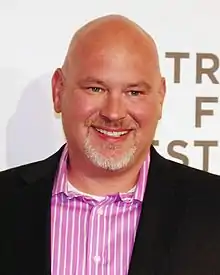

Notable alumni of the University of Delaware include 46th President of the United States, 47th Vice President of the United States and former U.S. Senator Joe Biden (B.A. 1965); First Lady of the United States Jill Biden (B.A. 1976); former New Jersey Governor Chris Christie (B.A. 1984); campaign manager David Plouffe (B.A. 2010); Nobel Prize-winning microbiologist Daniel Nathans (B.S. 1950); Nobel Prize-winning organic chemist Richard F. Heck; Henry C Brinton (BS Physics, 1957) Director of Research Division at NASA; Rwandan Minister of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation, Louise Mushikiwabo (M.A. 1988);[90] the former president of Emory University James W. Wagner (B.A. 1975); Chicago Bears Head Coach Matt Nagy; Super Bowl XLVII's MVP Joe Flacco; and 2008 John McCain campaign manager Steve Schmidt (B.A. 1993).[91]

- Notable University of Delaware alumni include:

George Read, 3rd President of Delaware and 1st U.S. Senator for Delaware, signer of the Declaration of Independence and U.S. Constitution

George Read, 3rd President of Delaware and 1st U.S. Senator for Delaware, signer of the Declaration of Independence and U.S. Constitution Thomas McKean, President of the Continental Congress, 2nd Governor of Pennsylvania and President of Delaware, signer of the Declaration of Independence

Thomas McKean, President of the Continental Congress, 2nd Governor of Pennsylvania and President of Delaware, signer of the Declaration of Independence Joe Biden, 46th President of the United States and 47th Vice President of the United States; former U.S. Senator for Delaware

Joe Biden, 46th President of the United States and 47th Vice President of the United States; former U.S. Senator for Delaware

.jpg.webp) Chris Christie, former Governor of New Jersey

Chris Christie, former Governor of New Jersey

Steve Schmidt, political communications strategist

Steve Schmidt, political communications strategist Richard F. Heck, Nobel Prize in Chemistry laureate

Richard F. Heck, Nobel Prize in Chemistry laureate Lodewijk van den Berg, astronaut

Lodewijk van den Berg, astronaut.jpeg.webp) Larry Probst, CEO of Electronic Arts

Larry Probst, CEO of Electronic Arts Elena Delle Donne, WNBA player for the Washington Mystics

Elena Delle Donne, WNBA player for the Washington Mystics

Partner Institution

Malaysia

- Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman[92] (through Anthropology 210: People and Cultures of Southeast Asia)

Repulic of Korea

Further reading

- Hofstetter, Fred T. (July 1, 1984). The Ninth Summative Report of the Office of Computer-Based Instruction (Report). University of Delaware, Office of Computer-Based Instruction – via Internet Archive.

The University of Delaware's work with computer-based instruction since 1974 is summarized, with attention to the history and development of the Office of Computer-Based Instruction, university applications, and research and development evaluation. (from abstract)

References

- As of June 30, 2019. "U.S. and Canadian 2019 NTSE Participating Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2019 Endowment Market Value, and Percentage Change in Market Value from FY18 to FY19 (Revised)". National Association of College and University Business Officers and TIAA. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- "Number of faculty by rank and tenure status Fall 2008 Through Fall 2012". University of Delaware. Archived from the original on June 1, 2013. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- "UD CONTINUES ENROLLMENT BOOM". University of Delaware. October 17, 2018. Archived from the original on October 16, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- "University of Delaware". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on February 8, 2018. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- "University of Delaware Brand Platform Style Guide" (PDF). November 15, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- "UD Facts and Figures, At A Glance" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- "Welcome to the University of Delaware". University of Delaware. Archived from the original on March 19, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- "Carnegie Classifications Institution Lookup". carnegieclassifications.iu.edu. Center for Postsecondary Education. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- "Table 20. Higher education R&D expenditures, ranked by FY 2018 R&D expenditures: FYs 2009–18". ncsesdata.nsf.gov. National Science Foundation. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- "Table 5. Higher education R&D expenditures". Archived from the original on March 26, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- "UD receives Carnegie Community Engagement Classification". UDaily. Archived from the original on July 30, 2019.

- "Welcome to Study Abroad". University of Delaware. Archived from the original on January 11, 2016. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- Munroe, John A. "The University of Delaware: A History". (University of Delaware, Newark, 1986). Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- Office of Communications and Marketing. "The History of the University of Delaware". University of Delaware. Archived from the original on February 1, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- Munroe, John A., The University of Delaware: A History (Newark: University of Delaware 1986)

- 1818 Delaware Laws, Ch. 157.

- 1835 Delaware Laws, Ch. 314.

- Thomas, Grace Powers, ed. (1898). Where to educate, 1898–1899. A guide to the best private schools, higher institutions of learning, etc., in the United States. Boston: Brown and Company. p. 40. OCLC 31539533. Archived from the original on October 17, 2012. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- "College for Delaware women formally established in October 1914". UDaily. University of Delaware. October 7, 2014. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved September 19, 2015. See also: The Blue Hen Archived December 15, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Classes of 1920/1921, p. 8 (retrieved December 14, 2017).

- Malcolm, Wade (May 7, 2011). "University of Delaware law school project delayed". The News Journal. Wilmington, Delaware. DelawareOnline. Archived from the original on May 7, 2011. Retrieved May 7, 2011. Only first of three online pages archived.

- "UDel, Chrysler reach agreement for plant sale". The News Journal. Wilmington, Delaware. October 23, 2009. Alt URL

- Malcolm, Wade (May 29, 2012). "UDel unveils plans for Chrysler site". The News Journal. New Castle, Delaware. DelawareOnline. Archived from the original on July 23, 2013. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2020: National/Regional Rank". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- "America's Top Colleges 2019". Forbes. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- "Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education College Rankings 2021". Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- "2021 Best National University Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- "2020 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2020". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- "QS World University Rankings® 2021". Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- "World University Rankings 2021". THE Education Ltd. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- "2021 Best Global Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report LP. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- "University of Delaware: Overall Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- "Online MPA Degree". University of Delaware. September 29, 2015. Archived from the original on October 5, 2016. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- "U.S. News Best Colleges Rankings - University of Delaware". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on May 19, 2017. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- "University of Delaware". Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- "Undergraduate Majors | College of Agriculture & Natural Resources | University of Delaware". www.udel.edu. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- "College of Arts & Sciences". University of Delaware. Archived from the original on December 16, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- "UD Facts and Figures". Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- "U.S. News and World Report, University of Delaware, Engineering School Overview". Archived from the original on April 4, 2017.

- "U.S. News and World Report, University of Delaware rankings". Archived from the original on May 19, 2017.

- "UD Facts and Figures". Archived from the original on September 13, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- "UDECU". University of Delaware. Archived from the original on March 2, 2013. Retrieved August 12, 2012.

- "IEC". University of Delaware. Archived from the original on June 18, 2012. Retrieved August 12, 2012.

- "Delaware Environmental Institute". University of Delaware. Archived from the original on July 24, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- "UDel ENERGY INSTITUTE". University of Delaware. Archived from the original on June 10, 2010. Retrieved July 3, 2010.

- "About Us | John L. Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance". University of Delaware. Archived from the original on April 30, 2013. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- "UDECU". University of Delaware. Archived from the original on May 26, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- "University of Delaware". University of Delaware. 2018. Archived from the original on February 5, 2007. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- "University of Delaware Map" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 17, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- "Image Gallery: Delaware State College Recitation Hall". Philadelphia Architects and Buildings. Athenaeum of Philadelphia. 2013. Archived from the original on February 24, 2012. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

- Ben-Joseph, E., Ben-Joseph, H.D., & Dodge, A.C. Against all Odds: MIT's Pioneering Women of Landscape Architecture Archived October 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. MIT, Cambridge, MA, 2006.

- Hail, M.W. "The Art of Landscaping Archived November 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine". University of Delaware Messenger, Vol. 2, No. 2, p. 4, (Winter) 1993.

- "University of Delaware Facilities Website – Residence Halls Information". University of Delaware. Archived from the original on October 31, 2010. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- McNeill, Rose (August 27, 2013). "UDel classes begin; new East Campus dorms open". The Newark Post. Newark, DE. Archived from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- Cherry, Amy (March 13, 2015). "University of Delaware names interim president". WDEL. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- "UD Facts and Figures 2015-2016" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 11, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- Kochanek, Lisa (July 7, 1923). "Study abroad celebrates 75th anniversary". University of Delaware. Archived from the original on April 8, 2010. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- The College Buzz Book. Vault Inc. 2006. p. 161. ISBN 9781581313994. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- "YoUDee Profile". BlueHens.com. University of Delaware. Archived from the original on July 24, 2017. Retrieved June 1, 2017.

- "Tubby Raymond named to College Football Hall of Fame". UDaily. University of Delaware. April 25, 2003. Archived from the original on July 3, 2009. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- "Division I Women's Lacrosse 25th Anniversary Team". April 13, 2006. Archived from the original on April 17, 2006. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

- "The History of the University of Delaware". University of Delaware. History at a glance. Archived from the original on February 1, 2010. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- Tresolini, Kevin (November 24, 2007). "Dominating: Cuff leads Blue Hens past Delaware State, 44–7". The News Journal. New Castle, Delaware. Archived from the original on December 19, 2007. Retrieved November 25, 2007.

- "UD, DSU add six football meetings, with surprising wrinkle". Delaware News Journal. July 1, 2019.

- "University's marching band selected for inaugural parade". UDaily. University of Delaware. December 9, 2008. Archived from the original on April 22, 2009. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- "The A Cappella Archive - Rankings & Records". sites.google.com. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- "Tuition set for 2019-20". Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- "About The Review". 2009. Archived from the original on May 1, 2013. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

- "About WVUD". Wvud.org. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- "Student Television Network". Stn49.tv. December 2, 2010. Archived from the original on April 1, 2009. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- University Student Centers. "Why Go Greek?". The University of Delaware. Archived from the original on July 15, 2015. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- "Chapter Assessment Program". University of Delaware. Archived from the original on November 17, 2010. Retrieved August 31, 2006.

- "Bishop, Binge Drinking in College". University of Delaware. Archived from the original on August 28, 2007. Retrieved February 4, 2007.

- "Crime Statistics". University of Delaware. Archived from the original on September 18, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2007.

- "Facts and Figures". University of Delaware. January 2010. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- "V8 Presents Opt 4". University of Delaware. Archived from the original on December 24, 2009. Retrieved January 4, 2007.

- Wang, Katie S. (November 9, 2008). "N.J. freshman dies from suspected alcohol poisoning at University of Delaware". The Star-Ledger. Archived from the original on October 17, 2012. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- "Student's death reveals gaps in policing parties". delawareonline. Archived from the original on September 21, 2016. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- "Transportation - Bus Routes". University of Delaware. Archived from the original on April 19, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- Steele, Karen (September 1, 1998). "Students Have Own Emergency Unit". National Collegiate EMS Foundation. Archived from the original on December 2, 2007.

- "UDel Emergency Care Unit marks 30 years of service". UDaily. University of Delaware. July 18, 2006. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- "September 3 Public Meeting- Questions and Answers" (Press release). September 3, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 3, 2014. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- Min, Shirley (April 9, 2014). "Delaware data center fight powers". NewsWorks. WHYY. Archived from the original on May 3, 2014. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- Nann Burke, Melissa (April 29, 2014). "Newark board upholds vote on gas-fired power plant". The News Journal. Wilmington, DE. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- Nann Burke, Melissa (April 17, 2014). "Campus task force says plant at odds with UD values". The News Journal. Wilmington, DE. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- Tuono, Nicolette (May 5, 2014). "Faculty Senate: Power plant not consistent with university's core values". UD Review. Archived from the original on May 13, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- Burke, Melissa Nann (May 6, 2014). "UDel faculty opposes gas-fired power plant". The News Journal. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- "UD terminates Data Centers project for STAR Campus". UDaily. University of Delaware. July 10, 2014. Archived from the original on September 12, 2015. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- Hoover, Eric (November 16, 2007). "U. of Delaware abandons sessions on diversity" (PDF). The Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 11, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- Twagilimana, Aimable (November 6, 2015). Historical Dictionary of Rwanda. ISBN 9781442255913.

- University of Delaware Messenger. "Leading the way to the White House". University of Delaware. Archived from the original on December 8, 2009. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- "University Partners - Division of Community and International Networking". Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman(UTAR). Archived from the original on July 19, 2019. Retrieved December 25, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to University of Delaware. |