Atlantic Coast Conference

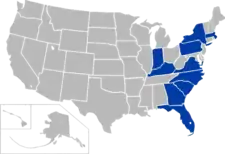

The Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) is a collegiate athletic conference located in the eastern United States. Headquartered in Greensboro, North Carolina, the conference consists of fifteen member universities, each of whom compete in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA)'s Division I, with its football teams competing in the Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS), the highest levels for athletic competition in US-based collegiate sports. The ACC sponsors competition in twenty-five sports with many of its member institutions' athletic programs held in high regard nationally. Current members of the conference are Boston College, Clemson University, Duke University, Georgia Institute of Technology, Florida State University, North Carolina State University, Syracuse University, the University of Louisville, the University of Miami, the University of North Carolina, the University of Notre Dame, the University of Pittsburgh, the University of Virginia, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, and Wake Forest University.

| Atlantic Coast Conference | |

|---|---|

| |

| Established | May 8, 1953 |

| Association | NCAA |

| Division | Division I |

| Subdivision | FBS |

| Members | 15 |

| Sports fielded |

|

| Region | |

| Headquarters | Greensboro, North Carolina |

| Commissioner | John Swofford (since July 1, 1997) |

| Website | www |

| Locations | |

| |

ACC teams and athletes have claimed dozens of national championships in multiple sports throughout the conference's history. Generally, the ACC's top athletes and teams in any particular sport in a given year are considered to be among the top collegiate competitors in the nation. Additionally, the conference enjoys extensive media coverage. The ACC was one of the five collegiate power conferences, which had automatic qualifying for their football champion into the Bowl Championship Series (BCS). With the advent of the College Football Playoff in 2014, the ACC is one of five conferences with a contractual tie-in to a New Year's Six bowl game, the successors to the BCS.

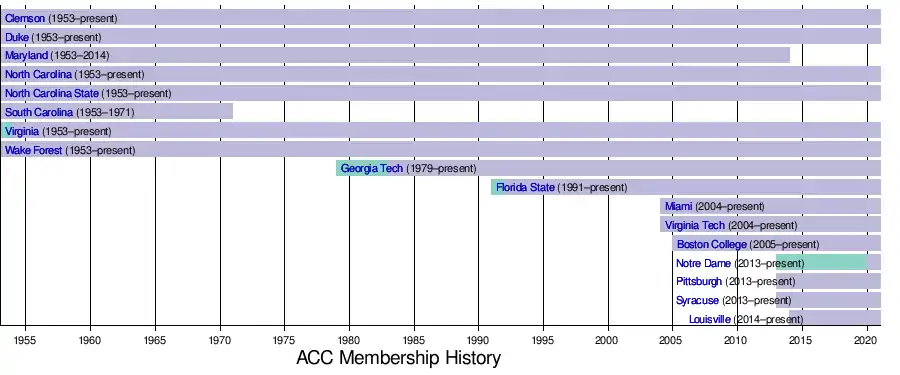

The ACC was founded on May 8, 1953, by seven universities located in the South Atlantic States, with the University of Virginia joining in early December 1953 to bring the membership to eight.[2] The loss of South Carolina in 1971 dropped membership to seven, while the addition of Georgia Tech in 1979 for non-football sports and 1983 for football brought it back to eight, and Florida State's arrival in 1991 for non-football sports and 1992 for football increased the membership to nine. Since 2000, with the widespread reorganization of the NCAA, seven additional schools have joined, and one original member (Maryland) has left to bring it to the current membership of 15 schools. The additions in recent years extended the conference's footprint into the Northeast and Midwest.

ACC member universities represent a range of private and public universities of various enrollment sizes, all of which participate in the Atlantic Coast Conference Academic Consortium whose purpose is to "enrich the educational missions, especially the undergraduate student experiences, of member universities".

Member universities

Current members

The ACC has 15 member institutions from 10 states. Listed in alphabetical order, these 10 states within the ACC's geographical footprint are Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kentucky, Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Virginia. The geographic domain of the conference is predominantly within the Southern and Northeastern United States along the US Atlantic coast and stretches from Florida in the south to New York in the North and from Indiana in the west to Massachusetts farthest east.

In two sports, football and baseball, the ACC is divided into two non-geographic divisions of seven teams each, labeled the "Atlantic" and "Coastal" divisions. Notre Dame does not participate in ACC football and Syracuse does not participate in ACC baseball (the Orange dropped baseball as a varsity sport after the 1971 season), leaving 14 total ACC schools for each of those sports. For all other sports, the ACC operates as a single unified league with no divisions.

When Notre Dame joined the ACC, it chose to remain a football independent. However, its football team established a special scheduling arrangement with the ACC to play a rotating selection of five ACC football teams per season. For the 2020 season, due largely to the suspension of most non-conference games by other Power Five conferences due to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, the ACC reached an agreement to allow Notre Dame to play a full, 10-game conference schedule and be eligible to play for the ACC championship.[3]

Since July 1, 2014, the 15 members of the ACC are:

- Although Florida State joined the ACC in 1991, it did not compete for the league's football championship until 1992.[4]

- Although Georgia Tech joined the ACC in 1979, it did not compete for the league's football championship until 1983.[5]

- Excludes enrollment at the university's four additional regional campuses. With those campuses added, the university's enrollment is 34,934.[6]

Former members

On July 1, 2014, the University of Maryland departed for the Big Ten Conference and the University of Louisville joined from the American Athletic Conference (formerly, the Big East Conference). In 1971, the University of South Carolina left the ACC to become an independent, later joining the Metro Conference in 1983 and moving to its current home, the Southeastern Conference, in 1991.

| Institution | Location | Founded | Joined | Left | Type (affiliation) | Current Conference | Nickname/Colors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of South Carolina | Columbia, South Carolina | 1801 | 1953 | 1971 | Public (USCS) | SEC | Gamecocks

|

| University of Maryland | College Park, Maryland | 1856

(as Maryland Agricultural College) |

1953 | 2014 | Public (USM) | Big Ten | Terrapins

|

Membership timeline

Full members Non-football members

History

Founding and early expansion

The ACC was established on June 14, 1953, when seven members of the Southern Conference left to form their own conference.[note 1][7] These seven universities became charter members of the ACC: Clemson, Duke, Maryland, North Carolina, North Carolina State, South Carolina, and Wake Forest. They left partially due to the Southern Conference's ban on post-season football play that had been initiated in 1951. (Clemson and Maryland had both defied the Southern Conference's bowl rule following the 1951 season and were banned from playing other conference teams in the 1952 season).[8] After drafting a set of bylaws for the creation of a new league, the seven withdrew from the Southern Conference at the spring meeting on the morning of May 8, 1953, at the Sedgefield Country Club in Greensboro, North Carolina. The bylaws were ratified on June 14, 1953, and the new conference was created.[9] The conference officials indicated a desire to add an eighth member, and candidates mentioned were Virginia and West Virginia.[10] On December 4, 1953, officials convened in Greensboro, North Carolina, and admitted Virginia, a former Southern Conference charter member that had been independent since 1937, into the conference.[11] Virginia's president Colgate Darden argued fiercely against joining the ACC or any conference, while UVA athletics director Gus Tebell argued in favor.[12] In the end, UVA's Board of Visitors approved joining the ACC by a vote of 6–3.[12]

In 1960, the ACC implemented a minimum SAT score for incoming student-athletes of 750, the first conference to do so. This minimum was raised to 800 in 1964, but was ultimately struck down by a federal court in 1972.[13]

On July 1, 1971, South Carolina left the ACC to become an independent.

Racial integration

Racial integration of all-white collegiate sports teams was high on the regional agenda in the 1950s and 1960s. Involved were issues of equality, racism, and the alumni demand for the top players needed to win high profile games. The ACC took the lead. First they started to schedule integrated teams from the north. Finally ACC schools—typically under pressure from boosters and civil rights groups—integrated their teams.[14] With an alumni base that dominated local and state politics, society and business, the ACC flagship schools were successful in their endeavor—as Pamela Grundy argues, they had learned how to win:

- The widespread admiration that athletic ability inspired would help transform athletic fields from grounds of symbolic play to forces for social change, places where a wide range of citizens could publicly and at times effectively challenge the assumptions that cast them as unworthy of full participation in U.S. society. While athletic successes would not rid society of prejudice or stereotype—black athletes would continue to confront racial slurs...[—minority star players demonstrated] the discipline, intelligence, and poise to contend for position or influence in every arena of national life.[15]

1978 & 1991 expansion

The ACC operated with seven members until the addition of Georgia Tech from the Metro Conference, announced on April 3, 1978, and taking effect on July 1, 1979, except in football, in which Tech would remain an independent until joining ACC football in 1983. The total number of member schools reached nine with the addition of Florida State, also formerly from the Metro Conference, on July 1, 1991, in non-football sports and July 1, 1992, in football. The additions of those schools marked the first expansions of the conference footprint since 1953, though both schools were still located with the rest of the ACC schools in the South Atlantic States.

2004–2005 expansion

The ACC added three members from the Big East Conference during the 2005 conference realignment: Miami and Virginia Tech joined on July 1, 2004, and Boston College joined on July 1, 2005, as the league's twelfth member and the first from the Northeast. The expansion was controversial, as Connecticut, Rutgers, Pittsburgh, and West Virginia (and, initially, Virginia Tech) filed lawsuits against the ACC, Miami, and Boston College for allegedly conspiring to weaken the Big East Conference.

2010–present

The ACC Hall of Champions opened on March 2, 2011, next to the Greensboro Coliseum arena, making the ACC the second college sports conference to have a hall of fame after the Southern Conference.[16][note 2]

On September 17, 2011, Big East Conference members Syracuse University and the University of Pittsburgh both applied to join the ACC.[18] The two schools were accepted into the conference the following day, once again expanding the conference footprint like previous expansions.[19] Because the Big East intended to hold Pitt and Syracuse to the 27-month notice period required by league bylaws, the most likely entry date into the ACC (barring negotiations) was July 1, 2014.[20] However, in July 2012, the Big East came to an agreement with Syracuse and Pitt that allowed the two schools to leave the Big East on July 1, 2013.[21][22]

On September 12, 2012, Notre Dame agreed to join the ACC in all conference sports except football as the conference's first member in the Midwestern United States. As part of the agreement, Notre Dame committed to play five football games each season against ACC schools beginning in 2014.[23] On March 12, 2013, Notre Dame and the Big East announced they had reached a settlement allowing Notre Dame to join the ACC effective July 1, 2013.[24]

On November 19, 2012, the University of Maryland's Board of Regents voted to withdraw from the ACC to join the Big Ten Conference effective in 2014.[25] The following week, the Big East's University of Louisville accepted the ACC's invitation to become a full member, replacing Maryland effective July 1, 2014.[26]

The ACC's presidents announced on April 22, 2013, that all 15 schools that would be members of the conference in 2014–15 had signed a grant of media rights (GOR), effective immediately and running through the 2026–27 school year, coinciding with the duration of the conference's then-current TV deal with ESPN. This move essentially prevents the ACC from being a target for other conferences seeking to expand—under the grant, if a school leaves the conference during the contract period, all revenue derived from that school's media rights for home games would belong to the ACC and not the school.[27] The move also left the SEC as the only one of the FBS Power Five conferences without a GOR.[28]

In July 2016, the GOR was extended through the 2035–36 school year, coinciding with the signing of a new 20-year deal with ESPN that would transform the then-current ad hoc ACC Network into a full-fledged network. The new network launched as a digital service in the 2016–17 school year and as a linear network in August 2019.[29]

Academics and ACCAC

Academic rankings

Among the major NCAA athletic conferences that sponsor NCAA Division I FBS football, including the current "Power Five conferences", the ACC has been regarded as having the highest academically ranked collection of members based on U.S. News & World Report[30][31][32][33][34][35] and by the NCAA's Academic Progress Rate.[36][37]

| School | Endowment[38] (in 2017 US$ billions) |

Major Faculty Awards[39](total awards) | Princeton Review Rating[40](scale 60–99) | US News US Ranking[41] | Washington Monthly US Ranking[42] | ARWU US Ranking[43] | NTU US Ranking[44] | CWTS Leiden US Impact Ranking[45] | Scimago US Higher Education Ranking[46] | URAP US Ranking[47] | US News/QS World Rankings[48] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston College | $2.477700 | 6 | 85 | 37 | 57 | 100 | 138 | 155 | 123 | 145 | 339 |

| Clemson | $0.741802 | 3 | 78 | 70 | 114 | 156 | 138 | 110 | 125 | 123 | 701 |

| Duke | $7.911175 | 30 | 92 | 10 | 12 | 20 | 14 | 15 | 14 | 16 | 21 |

| Florida State | $0.681370 | 9 | 68 | 57 | 81 | 70 | 91 | 81 | 107 | 75 | 431 |

| Georgia Tech | $2.091110 | 21 | 86 | 29 | 31 | 43 | 47 | 41 | 32 | 45 | 70 |

| Louisville | $0.712295 | 5 | 69 | 192 | 221 | 156 | 119 | 103 | 105 | 110 | 1001 |

| Miami | $1.021508 | 7 | 78 | 57 | 277 | 61 | 59 | 58 | 41 | 54 | 252 |

| North Carolina | $3.432911 | 19 | 77 | 29 | 23 | 23 | 20 | 23 | 18 | 21 | 80 |

| North Carolina State | $1.293743 | 11 | 75 | 84 | 84 | 71 | 72 | 43 | 57 | 56 | 263 |

| Notre Dame | $10.727653 | 14 | 80 | 15 | 22 | 71 | 101 | 96 | 93 | 87 | 216 |

| Pittsburgh | $4.200206 | 13 | 80 | 57 | 143 | 35 | 17 | 13 | 20 | 19 | 142 |

| Syracuse | $1.338287 | 11 | 77 | 54 | 28 | 156 | 138 | 145 | 172 | 129 | 501 |

| Virginia | $6.953380 | 15 | 87 | 28 | 36 | 61 | 53 | 50 | 55 | 46 | 173 |

| Virginia Tech | $1.146055 | 10 | 73 | 74 | 19 | 100 | 95 | 53 | 65 | 63 | 367 |

| Wake Forest | $1.329255 | 3 | 94 | 27 | 75 | 136 | 86 | 95 | 85 | 88 | 411 |

ACCAC and ACC academic network

The members of the ACC participate in the Atlantic Coast Conference Academic Consortium (ACCAC), a consortium that provides a vehicle for inter-institutional academic and administrative collaboration between member universities. Growing out of a conference-wide doctoral student-exchange program that was established in 1999, the ACCAC has expanded its scope into other domestic and international collaborations.[49]

The stated mission of the ACCAC is to "leverage the athletic associations and identities among the 15 ACC universities in order to enrich the educational missions of member universities." To that end, the collaborative helps organize various academic initiatives, including fellowship and scholarship programs, global research initiatives, leadership conferences, and extensive study abroad programs.[50] Funding for its operations, 90% of which is spent on direct student support, is derived from a portion of the income generated by the ACC Football Championship Game and by supplemental allocations by individual universities and various grants.[51]

ACCAC academic programs

Major academic programs that have been implemented under ACCAC include:

- The annual Meeting of the Minds (MOM) undergraduate research conference.[52]

- The annual Student Leadership Conference.[53]

- The Creativity and Innovation Fellowship Program in which each university receives $12,500 to award between two and five undergraduate students ACCAC fellowships for research or creative projects.[54]

- The Summer Research Scholars Program in which every ACC university will receive $5,000 to support up to two of its undergraduate students in conducting research in residence at another ACC university during a minimum 10 week period over the summer.[55]

- The ACC Debate Championship[56]

- The ACC Inventure Prize Competition is a Shark Tank-like innovation competition for teams of students from ACC universities.[57]

- The Student Federal Relations Trip to Washington, D.C. is an annual trip of student delegates from ACC universities to the nation's capital.[58]

- The Creativity Competition is planned to be an ACC-wide, team-based interdisciplinary competition emphasizing use of creative design and the arts to begin in 2017.[58]

- The Distinguished Lecturers Program in which five ACC universities select an outstanding faculty member as The ACCAC's Distinguished Lecturer. In addition to an award stipend, the ACCAC provides financial support to enable each ACC university to sponsor a "distinguished lecture event" on their campus.[59]

- The Executive Leadership Series is a two-day skill enhancement programs designed for Deans, Vice Provosts, and Vice Chancellors of ACC universities.[58]

- The annual Student President Conference.[60]

- The Coach for College Program, primarily for student-athletes and run through Duke University with support from the ACCAC, that takes 32 ACC students to Vietnam for three weeks in the summer to coach hundreds of middle school children.[61]

- The Traveling Scholars Program which allows PhD candidates from one ACC campus to access courses, laboratories, library, or other resources at any one of the other ACC member institution campuses.[62]

- The Clean Energy Grant Competition that helps coordinate geographically defined clusters of ACC universities in competition for United States Department of Energy Clean Energy Grants.[62]

- The Study Abroad Program collaborative which allows cross registration in study abroad programs enroll in programs sponsored by an ACC university other than their "home" university.[62] A Student Study Abroad Scholarship program that awarded two to five ACCAC scholarships for study abroad was discontinued in 2013, but is targeted for renewal in 2014–15.[63]

The ACCAC also supports periodic meetings among faculty, administration, and staff who pursue similar interests and responsibilities at the member universities either by face-to-face conferences, video conferences, or telephone conferences. ACCAC affinity groups include those for International Affairs Officers, Study Abroad Directors, Teaching-Learning Center Directors, Chief Information Officers, Chief Procurement Officers, Undergraduate Research Conference Coordinators, Student Affairs Vice Presidents, Student Leadership Conference Coordinators, and Faculty Athletic Representatives To the ACC.[64]

Spending and revenue

Total revenue includes ticket sales, contributions and donations, rights/licensing, student fees, school funds, and all other sources including TV income, camp income, food, and novelties. Total expenses includes coaching/staff, scholarships, buildings/grounds, maintenance, utilities and rental fees, and all other costs including recruiting, team travel, equipment and uniforms, conference dues, and insurance costs.

| Conference Rank (2016–17) |

National Rank (2016–17) |

Institution | 2016-17 Total Revenue from Athletics[65] | 2016-17 Total Expenses on Athletics[65] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 | Florida State University | $144,514,413 | $143,373,261 |

| 2 | 22 | University of Louisville | $120,445,303 | $118,383,769 |

| 3 | 26 | Clemson University | $112,600,964 | $111,126,235 |

| 4 | 35 | University of North Carolina | $96,551,626 | $96,540,823 |

| 5 | 39 | University of Virginia | $92,865,175 | $100,324,517 |

| 6 | 44 | Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University | $87,427,526 | $90,716,423 |

| 7 | 47 | North Carolina State University | $83,741,572 | $86,924,779 |

| 8 | 51 | Georgia Institute of Technology | $81,762,024 | $84,852,123 |

| N/A | N/A | Boston College | Not reported | Not reported |

| N/A | N/A | Duke University | Not reported | Not reported |

| N/A | N/A | Syracuse University | Not reported | Not reported |

| N/A | N/A | University of Miami | Not reported | Not reported |

| N/A | N/A | University of Notre Dame | Not reported | Not reported |

| N/A | N/A | University of Pittsburgh | Not reported | Not reported |

| N/A | N/A | Wake Forest University | Not reported | Not reported |

Facilities

Sports

The Atlantic Coast Conference sponsors championship competition in thirteen men's and fourteen women's NCAA-sanctioned sports.[67] The most recently added sport was fencing, added for the 2014–15 school year after having been absent from the conference since 1980; Boston College, Duke, North Carolina, and Notre Dame participate in that sport.[68]

Since all ACC members (including non-football member Notre Dame) field FBS football teams, they are subject to the NCAA requirement that FBS schools field at least 16 NCAA-recognized varsity sports. However, the ACC itself requires sponsorship of only four sports—football, men's basketball, women's basketball, and either women's soccer or women's volleyball.[69] All ACC members sponsor all five of the named sports except Georgia Tech, which sponsors women's volleyball but not women's soccer.

| Sport | Men's | Women's |

|---|---|---|

| Baseball | 14 | |

| Basketball | 15 | 15 |

| Cross country | 15 | 15 |

| Fencing | 4 | 4 |

| Field hockey | 7 | |

| Football | 15 | |

| Golf | 12 | 12 |

| Lacrosse | 5 | 8 |

| Rowing | 9 | |

| Soccer | 12 | 14 |

| Softball | 12 | |

| Swimming & diving | 11.5 | 12 |

| Tennis | 13 | 14 |

| Track and field (indoor) | 15 | 15 |

| Track and field (outdoor) | 15 | 15 |

| Volleyball | 15 | |

| Wrestling | 6 |

Men's sponsored sports by school

Member-by-member sponsorship of the 13 men's ACC sports for the 2020–21 academic year.

| School | Baseball | Basketball | Cross country | Fencing | Football | Golf | Lacrosse | Soccer | Swimming & diving | Tennis | Track & field (indoor) | Track & field (outdoor) | Wrestling | Total ACC men's sports |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston College | 11 | |||||||||||||

| Clemson | 9 | |||||||||||||

| Duke | 13 | |||||||||||||

| Florida State | 9 | |||||||||||||

| Georgia Tech | 9 | |||||||||||||

| Louisville | 10 | |||||||||||||

| Miami | 7.5 | |||||||||||||

| North Carolina | 13 | |||||||||||||

| North Carolina State | 11 | |||||||||||||

| Notre Dame | 12 | |||||||||||||

| Pittsburgh | 9 | |||||||||||||

| Syracuse | 7 | |||||||||||||

| Virginia | 12 | |||||||||||||

| Virginia Tech | 11 | |||||||||||||

| Wake Forest | 9 | |||||||||||||

| Totals | 14 | 15 | 15 | 4 | 15 | 12 | 5 | 12 | 11.5 | 13 | 15 | 15 | 6 | 151.5 |

- Clemson will drop its men's program in the sport of athletics (i.e, cross country and track & field) after the 2020–21 school year.[70]

- Miami participates in diving only. For the purposes of this chart, Miami men's diving is counted as sponsoring half of the sport of men's swimming & diving.

Men's varsity sports not sponsored by the Atlantic Coast Conference which are played by ACC schools:

| School | Ice hockey | Rifle | Rowing[lower-alpha 1] | Sailing[lower-alpha 1] | Skiing | Squash [lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston College | Hockey East | no | no | NEISA | EISA | no |

| North Carolina State | no | GARC & SEARC[lower-alpha 2] | no | no | no | no |

| Notre Dame | Big Ten | no | no | no | no | no |

| Syracuse | ESCHL[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 3] | no | EARC | no | no | no |

| Virginia | no | no | no | no | no | Independent[71] |

- Not governed or recognized by the NCAA.

- Co-ed Rifle Team

- Not recognized by Syracuse University as a varsity team.

Women's sponsored sports by school

Member-by-member sponsorship of the 14 women's ACC sports for the 2020–21 academic year.

| School | Basketball | Cross country | Fencing | Field hockey | Golf | Lacrosse | Rowing | Soccer | Softball | Swimming & diving | Tennis | Track & field (indoor) | Track & field (outdoor) | Volleyball | Total ACC women's sports |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston College | 14 | ||||||||||||||

| Clemson | 10 | ||||||||||||||

| Duke | 14 | ||||||||||||||

| Florida State | 10 | ||||||||||||||

| Georgia Tech | 8 | ||||||||||||||

| Louisville | 13 | ||||||||||||||

| Miami | 10 | ||||||||||||||

| North Carolina | 14 | ||||||||||||||

| North Carolina State | 10 | ||||||||||||||

| Notre Dame | 13 | ||||||||||||||

| Pittsburgh | 8 | ||||||||||||||

| Syracuse | 11 | ||||||||||||||

| Virginia | 13 | ||||||||||||||

| Virginia Tech | 11 | ||||||||||||||

| Wake Forest | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| Totals | 15 | 15 | 4 | 7 | 12 | 8 | 9 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 169 |

- Pitt to add women's lacrosse beginning in the 2022 season (2021–22 school year).[72]

Women's varsity sports not sponsored by the Atlantic Coast Conference which are played by ACC schools:

| School | Beach volleyball | Gymnastics | Ice hockey | Rifle | Sailing[lower-alpha 1] | Skiing | Squash[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston College | no | no | Hockey East | no | NEISA | EISA | no |

| Florida State | CCSA | no | no | no | no | no | no |

| North Carolina | no | EAGL | no | no | no | no | no |

| North Carolina State | no | EAGL | no | GARC & SEARC[lower-alpha 2] | no | no | no |

| Pittsburgh | no | EAGL | no | no | no | no | no |

| Syracuse | no | no | CHA | no | no | no | no |

| Virginia | no | no | no | no | no | no | Independent[71] |

- Not governed or recognized by the NCAA.

- Co-ed Rifle Team

Current champions

Champions from the previous academic year are indicated in italics.

| Season | Sport | Men's champion | Women's champion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fall 2019 | Cross country[73] | Syracuse | NC State |

| Field hockey[74] | – | North Carolina | |

| Football[75] | Clemson | – | |

| Soccer | Virginia[76] | North Carolina[77] | |

| Volleyball | – | – | |

| Winter 2019–20 | Basketball | Canceled[lower-alpha 1] | NC State[78] |

| Fencing[79] | Notre Dame | Notre Dame | |

| Swimming & diving | NC State[80] | Virginia[81] | |

| Track & field (Indoor)[82] | Florida State | Virginia Tech | |

| Wrestling | NC State[83] | – | |

| Spring 2020 | Baseball | Canceled | – |

| Softball | – | Canceled | |

| Golf | Canceled | Canceled | |

| Lacrosse | Canceled | Canceled | |

| Rowing | – | Canceled | |

| Tennis | Canceled | Canceled | |

| Track & field (outdoor) | Canceled | Canceled |

- Florida State, as the top seed of the tournament, was awarded the conference's automatic bid to the NCAA Tournament.

Football

The ACC is considered to be one of the Power Five conferences, all of which receive automatic placement of their football champions into one of the six major bowl games. Seven of its members claim football national championships in their history, with two having won the now-defunct Bowl Championship Series (BCS) during its existence between 1998 and 2014 and one having won under the current College Football Playoff (CFP) system. Five of its members are among the top 25 of college football's all-time winningest programs.[84] Three ACC teams, Florida State, Miami, and Clemson, are listed in the top 10 of most successful football programs since 2000.

Divisions and scheduling

In 2005, the ACC began divisional play in football. The ACC is the only NCAA Division I conference whose divisions are not divided geographically (e.g., North/South, East/West),[85] but rather into Atlantic and Coastal (as above). Division leaders compete in the ACC Championship Game to determine the official conference title, which guarantees a berth in a New Year's Six bowl game. The inaugural Championship Game was played on December 3, 2005, in Jacksonville, Florida, at the venue then known as Alltel Stadium, in which Florida State defeated Virginia Tech to capture its 12th championship since it joined the league in 1992. Notre Dame began playing several ACC teams each year in 2014, but is not considered a football member and is not eligible to play in the ACC Championship Game.[86]

The current division structure leads to each team playing the following games:

- Six games within its division (three home, three away, one against each opponent).

- One game against a designated permanent rival from the other division (not necessarily the school's closest traditional rival, even within the conference); this is similar to the SEC setup.

- The permanent cross-division matchups are as follows,[87] with the Atlantic Division member listed first: Boston College–Virginia Tech; Clemson–Georgia Tech; Florida State–Miami; Louisville–Virginia; NC State–North Carolina; Syracuse–Pittsburgh; Wake Forest–Duke.

- One rotating game against a team in the other division, for a total of two cross-division games.

- Non-permanent cross-division opponents face each other in the regular season twice in a span of twelve years.

- Prior to the addition of Syracuse and Pittsburgh in 2013, teams played two rotating cross-division games (for a total of three cross-division games), with a total of eight conference games. The addition of one team to each division meant the loss of one cross-division game per year.[88]

- Four non-conference games.

- As of the 2014 season, one of the four non-conference games is against Notre Dame every two to three years, as Notre Dame plays against five ACC opponents in non-conference games each season.

- Starting with the 2017 season, ACC members will be required to play at least one non-conference game each season against a team in the "Power 5" conferences. Games against Notre Dame also meet the requirement. In January 2015, the conference announced that games against another FBS independent, BYU, would also count toward the requirement.[89]

- ACC teams can also meet the requirement by scheduling one another in non-conference games; the first example of this was also announced in January 2015, when North Carolina and Wake Forest announced that they would play a home-and-home non-conference series in 2019 and 2021.[90]

For the 2020 season, changes were made to the football schedule model due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The use of divisions was suspended, with conference games being scheduled on a regional basis. The top two teams by winning percentage against conference opponents will advance to the ACC Championship Game. All teams will play 10 conference games, and may play one non-conference game of their choice as long as the game is played in-state. In addition, Notre Dame will play an ACC conference schedule and also be eligible to play in the ACC Championship Game.[3]

Bowl games

Within the College Football Playoff, the Orange Bowl serves as the home of the ACC champion against Notre Dame or another team from the SEC or Big Ten. If the conference's champion is selected for the CFP, another ACC team will be chosen in their place.

The other bowls pick ACC teams in the order set by agreements between the conference and the bowls.

Beginning in 2014, Notre Dame is eligible for selection as the ACC's representative to any of its contracted bowl games. The ACC's bowl selection will no longer be bound by the rigidity of a "one-win rule" but will have a general list of criteria to emphasize regionality and quality matchups on the field. A one-win rule does apply to Notre Dame's participation in the ACC Bowl structure. Notre Dame is now eligible for ACC Bowl selection beginning with the Outback Bowl and continuing through the league's bowl selections. However, Notre Dame must be within one win of the ACC available team which has the best overall record, in order to be chosen. In other words, if an ACC team was 9-3, a 7-5 Notre Dame team could not be chosen in its place. Notre Dame would have to be 8-4 to be chosen over a 9-3 league team. For the 2020 season, Notre Dame is competing for the ACC conference championship and is eligible for all games, including the Orange Bowl.

| Pick | Name | Location | Opposing Conference | Opposing Pick |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1* | Orange Bowl | Miami Gardens, Florida | SEC, Big Ten or Notre Dame | - |

| Tier One All have equal selection status | ||||

| 2/3/4/5/6/7/8/9 | Outback Bowl** | Tampa, Florida | SEC | TBD [92] |

| Cheez-It Bowl | Orlando, Florida | Big 12 | 3[93] | |

| Sun Bowl | El Paso, Texas | Pac-12 | 5[94] | |

| Duke's Mayo Bowl | Charlotte, North Carolina | SEC or Big Ten | TBD[95] | |

| Gator Bowl | Jacksonville, Florida | SEC | ||

| Pinstripe Bowl | The Bronx, New York | Big Ten | ||

| Holiday Bowl | San Diego, California | Pac-12 | ||

| Military Bowl | Annapolis, Maryland | The American | ||

| Fenway Bowl | Boston, Massachusetts | The American | ||

| Tier Two One ACC school will be selected to play in one of the following games | ||||

| 10 | ||||

| Gasparilla Bowl | St. Petersburg, Florida | The American | TBD | |

| Birmingham Bowl | Birmingham, Alabama | C-USA, MAC | TBD | |

| First Responder Bowl | Dallas, Texas | TBD | TBD | |

* If the ACC Champion is not in one of the semifinal games it will appear in the Orange Bowl or, if the Orange Bowl is a semifinal site, either the Peach Bowl or the Fiesta Bowl. There is no limit on how many teams the College Football Playoff may choose from a particular conference.

** Only if the ACC opponent in the Orange Bowl, in a non-semifinal year is a team from the Big Ten, a maximum of three times in six years.

National championships

Although the NCAA does not determine an official national champion for Division I FBS football, several ACC members claim national championships awarded by various "major selectors" of national championships as recognized in the official NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision Records.[96] Since 1936 and 1950 respectively, these include what are now the most pervasive and influential selectors, the Associated Press poll and Coaches Poll. In addition, from 1998 to 2013 the Bowl Championship Series (BCS) used a mathematical formula to match the top two teams at the end of the season. The winner of the BCS was contractually awarded the Coaches' Poll national championship and its AFCA National Championship Trophy as well as the MacArthur Trophy from the National Football Foundation. Maryland won one championship as a member of the ACC in 1953.

| School | Claims of non-poll "major selectors" |

Associated Press | Coaches Poll | Bowl Championship Series | College Football Playoff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clemson | 1981, 2016, 2018 | 1981, 2016, 2018 | 2016, 2018 | ||

| Florida State | 1993, 1999, 2013 | 1993, 1999, 2013 | 1999, 2013 | ||

| Georgia Tech | 1917, 1928, 1952 | 1990 | |||

| Miami | 1983, 1987, 1989, 1991, 2001 | 1983, 1987, 1989, 2001 | 2001 | ||

| Pittsburgh | 1915, 1916, 1918, 1929, 1931, 1934, 1936[lower-alpha 1] | 1937, 1976 | 1976 | ||

| Syracuse | 1959 | 1959 |

- Italics denote championships won before the school joined the ACC.

- In addition, non-football member Notre Dame claims 11 national titles. Many sources, however, credit the Fighting Irish with 13. See Notre Dame Fighting Irish football national championships for more details.

- A "list of college football's mythical champions as selected by every recognized authority since 1924" was printed in Sports Illustrated in 1967.[97] Together with the 1976 national championship which would come later, the national championship selections listed by Sports Illustrated have since served as the historical basis of the university's national championship claims.[98] For the 1934 season, the Sports Illustrated article included a selection by Parke Davis, then deceased, which had appeared the 1935 edition of the annual Spalding's Football Guide under Davis' byline. The 1934 selection is not documented in the Official NCAA Football Records Book with the rest of Pitt's claimed seasons, although additional major selections for Pitt, which are not claimed by the university, are listed in 1910, 1980, and 1981.[99] College Football Data Warehouse recognizes nine championships for Pitt (1910, 1915, 1916, 1918, 1929, 1931, 1936, 1937, and 1976)[100] out of the 16 years which it has documented that Pitt was named as a national champion by various selectors.[101]

Basketball

History

The early roots of ACC basketball began primarily thanks to two men: Everett Case and Frank McGuire. Case accepted the head coaching job at North Carolina State. Case's North Carolina State teams dominated the early years of the ACC with a modern, fast-paced style of play. He became the fastest college basketball coach to reach many "games won" milestones. Case became known as The Father of ACC Basketball. Despite his success on the court, he may have been even a better promoter off-the-court. Case realized the need to sell his program and university. State started construction on Reynolds Coliseum in 1941. Case persuaded school officials to expand the arena to 12,400 people. It opened as the new home court for his team in 1949; at the time, it was the largest on-campus arena in the South. As such, it was used as the host site for many Southern Conference Tournaments, ACC Tournaments, and the Dixie Classic. The Dixie Classic brought in large revenues for all schools involved and soon became one of the premier sporting events in the South.

Partly to counter Case's success, North Carolina convinced Frank McGuire to come to Chapel Hill in 1952. McGuire knew that, largely due to Case's influence, basketball was now the major high school athletic event of the region. He not only tapped the growing market of high school talent in North Carolina, but also brought several recruits from his home territory in New York City as well. Case and McGuire literally invented a rivalry. Both men realized the benefits created through a rivalry between them. It brought more national attention to both of their programs and increased fan support on both sides.

After State was slapped with crippling NCAA sanctions before the 1956–57 season, McGuire's North Carolina team delivered the ACC its first national championship. During the Tar Heels' championship run, Greensboro entrepreneur Castleman D. Chesley noticed the popularity that it generated. He cobbled together a five-station television network to broadcast the Final Four. That network began broadcasting regular season ACC games the following season—the ancestor of the television package from Raycom Sports. From that point on, ACC basketball gained large popularity.

The ACC has been the home of many prominent basketball coaches besides Case and McGuire, including Terry Holland and Tony Bennett of Virginia; Vic Bubas and Mike Krzyzewski of Duke; Press Maravich, Norm Sloan and Jim Valvano of North Carolina State; Dean Smith and Roy Williams of North Carolina; Bones McKinney of Wake Forest; Lefty Driesell and Gary Williams of Maryland; Bobby Cremins of Georgia Tech; Jim Boeheim of Syracuse; and Rick Pitino of Louisville.

Tournament as championship

Possibly Case's most lasting contribution is the ACC Tournament, which was first played in 1954 and decides the winner of the ACC title. The ACC is unique in that it is the only Division I college basketball conference that does not officially recognize a regular season champion. This started when only one school per conference made the NCAA tournament. The ACC representative was determined by conference tournament rather than the regular season result. Therefore, the league eliminated the regular season title in 1961, choosing to recognize only the winner of the ACC tournament as conference champion. Fans and media do claim a regular-season title for the team that finishes first, and the NCAA recognizes a regular-season title winner in order to maintain its system of choosing NIT and NCAA tournament berths based on regular season placement.[102] For the ACC, the unofficial crowning of a regular season champion is insignificant as a 1975 NCAA rule change allowed more than one team per conference to earn a bid to the NCAA Tournament. As a result, the team finishing atop the ACC regular-season standings has invariably been invited to the NCAA Tournament even if it did not win the ACC Tournament. Even so, any claim to a regular season "title" remains unofficial and carries no reward other than top seed in the ACC tournament.

Historically, the ACC has been dominated by the four teams from Tobacco Road in North Carolina—North Carolina, Duke, North Carolina State and Wake Forest. Between them, they have won 50 tournament titles. They have also won or shared 59 regular season titles, including all but four since 1981. The Virginia Cavaliers, however, won the regular season titles in 2014 and 2015, becoming the first ACC team besides Duke or North Carolina to solely win back-to-back regular season titles since 1974.

Present-day schedule

For 53 years, the ACC employed a double round-robin schedule in the regular season, in which each team played the others twice a season. With the expansion to 12 members by the 2005–2006 season, the ACC schedule could no longer accommodate this format. In the new scheduling format that was agreed to, each team was assigned two permanent partners and nine rotating partners over a three-year period.[103] Teams played their permanent partners in a home-and-away series each year. The rotating partners were split into three groups: three teams played in a home-and-away series, three teams played at home, and three teams played on the road. The rotating partner groups were rotated so that a team would play each permanent partner six times, and each rotating partner four times, over a three-year period.

For the 2012–13 season, the 12-team in-conference schedule expanded to 18. Originally for the 2013–14 season, the expanded 14-team, 18-game schedule was to consist of a home and away game with a "primary partner" while the remaining conference opponents would have rotated in groups of three: one year both home and away, one year at home only, and one year away only.[104] However, when Notre Dame was also added for the 2013–14 season, the now 15-team, 18-game schedule was modified so each school played two "Partners" home and away annually, two home and away, five home, and the other five away.[105] In 2013–14, after 1 year at 18 games, women's basketball went back to a 16-game schedule where each team only plays 2 teams twice, rotating opponents each year over seven years and has no permanent partners.

The ACC and the Big Ten Conference have held the ACC–Big Ten Challenge each season since 1999. The competition is a series of regular-season games pitting ACC and Big Ten teams against each other. Each team typically plays one Challenge game each season, except for a few teams from the larger conference that are left out due to unequal conference sizes. The first ACC–Big Ten Women's Challenge was played in 2007, and has the same format as the men's Challenge.

National championships and Final Fours

Over the course of its existence, ACC schools have captured 15 NCAA men's basketball championships while members of the conference. North Carolina has won six, Duke has won five, NC State has won two, and Maryland and Virginia have each won one. Four more national titles were won by current ACC members while in other conferences—three by 2014 arrival Louisville and one by 2013 arrival Syracuse; Louisville was forced to vacate the third national title due to NCAA sanctions. Seven of the 12 pre-2013 members have advanced to the Final Four at least once while members of the ACC. Another pre-2013 member, Florida State, made the Final Four once before joining the ACC. All three schools that entered the ACC in 2013, as well as Louisville, advanced to the Final Four at least once before joining the conference.

Also notable are earlier national championships from historical eras prior to the dominance of the NCAA-administered championship. The ACC is often credited with forcing the NCAA tournament to expand to allow more than one team per conference, creating the at-large NCAA field common today.[106] The Helms Athletic Foundation selected national champions for seasons predating the beginning of the NCAA tournament (1939), including North Carolina, Notre Dame, Pitt, and Syracuse. Prior to the at-large era (1975), the National Invitation Tournament championship had prestige comparable to the NCAA championship, and Louisville, North Carolina, Maryland, and Virginia Tech won titles during this period (later NIT titles are not considered consensus national championships).[107]

In women's basketball, ACC members have won three national championships while in the conference, North Carolina in 1994, Maryland in 2006, and Notre Dame in 2018. Notre Dame, which joined in 2013, also previously won the national title in 2001. In 2006, Duke, Maryland, and North Carolina all advanced to the Final Four, the first time a conference placed three teams in the women's Final Four. Both finalists were from the ACC, with Maryland defeating Duke for the title.

| School | Pre-NCAA Helms Championships | NCAA Men's Championships | Men's NCAA Runner-Up |

Men's NCAA Final Fours | NCAA Women's Championships | Women's NCAA Runner-Up |

Women's NCAA Final Fours |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Carolina | 1 (1924) |

6 [o 1] |

5 (2016, 1981, 1977, 1968, 1946) |

20 [o 2] |

1 (1994) |

3 (2007, 2006, 1994) | |

| Duke | 5 (2015, 2010, 2001, 1992, 1991) |

6 [o 3] |

16 [o 4] |

2 (2006, 1999) |

4 (2006, 2003, 2002, 1999) | ||

| Louisville | 3 (1980, 1986, 2013*)[o 5] |

10 [o 6] |

2 (2013, 2009) |

3 (2018, 2013, 2009) | |||

| Syracuse | 2 (1926, 1918) |

1 (2003) |

2 (1996, 1987) |

6 [o 7] |

1 (2016) |

1 (2016) | |

| North Carolina State | 2 (1983, 1974) |

3 (1983, 1974, 1950) |

1 (1998) | ||||

| Virginia | 1 (2019) |

3 (2019, 1984, 1981) |

1 (1991) |

3 (1992, 1991, 1990) | |||

| Georgia Tech | 1 (2004) |

2 (2004, 1990) |

|||||

| Notre Dame | 2 (1936, 1927) |

1 (1978) |

2 (2018, 2001) |

4 (2019, 2015, 2014, 2012, 2011) |

7 [o 8] | ||

| Florida State | 1 (1972) |

1 (1972) |

|||||

| Wake Forest | 1 (1962) |

||||||

| Pittsburgh | 2 (1930, 1928) |

1 (1941) |

Italics denotes honors earned before the school joined the ACC. Women's national championship tournaments prior to 1982 were run by the AIAW.

- North Carolina has won the NCAA men's championship six times (2017, 2009, 2005, 1993, 1982, 1957)

- North Carolina has reached the Final Four 20 times (2017, 2016, 2009, 2008, 2005, 2000, 1998, 1997, 1995, 1993, 1991, 1982, 1981, 1977, 1972, 1969, 1968, 1967, 1957, 1946)

- Duke has been the men's NCAA runner-up 6 times (1999, 1994, 1990, 1986, 1978, 1964)

- Duke has reached the Final Four 16 times (2015, 2010, 2004, 2001, 1999, 1994, 1992, 1991, 1990, 1989, 1988, 1986, 1978, 1966, 1964, 1963)

- Louisville's third national title, in 2013, was vacated in 2018 due to NCAA sanctions.

- Louisville has reached the Final Four 10 times (2013*, 2012*, 2005, 1986, 1983, 1982, 1980, 1975, 1972, 1959). Two Final Four appearances (2013, 2012) were later vacated due to NCAA sanctions.

- Syracuse has reached the Final Four six time (2016, 2013, 2003, 1996, 1987, 1975)

- Notre Dame has reached the Women's Final Four 7 times (2018, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2001, 1997)

Baseball

ACC Baseball is divided into the Atlantic and Coastal Divisions (as above). These divisions parallel the divisions of ACC football except with Notre Dame replacing Syracuse, the only ACC school which does not field a baseball team, within the Atlantic Division, giving both divisions seven teams. Louisville replaced Maryland in the Atlantic Division beginning with the 2015 season.

Eight ACC teams were selected to play in the 2019 NCAA Division I Baseball Tournament, with Florida State and Louisville advancing to the College World Series. The ACC has won the College World Series twice: by the Virginia Cavaliers in 2015 and by Wake Forest in 1955. In addition, Miami won four titles before joining the ACC,[108] and South Carolina has won two titles since leaving the league. Current member schools have appeared in the College World Series a combined total of 93 times (including appearances before joining the conference). In 2016, the ACC was ranked as the top baseball conference by Rating Percentage Index (RPI); the conference has ranked among the top three by this measure each of the past 10 years.[109]

| School | College World Series Championships |

College World Series Appearances |

Last CWS Appearance |

NCAA Tournament Appearances |

Last NCAA Appearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miami † | 2001, 1999, 1985, 1982 |

25 | 2016 | 46 | 2019 |

| Virginia | 2015 | 4 | 2015 | 17 | 2017 |

| Wake Forest | 1955 | 2 | 1955 | 14 | 2017 |

| Florida State † | 23 | 2019 | 57 | 2019 | |

| Clemson | 12 | 2010 | 44 | 2019 | |

| North Carolina | 11 | 2018 | 32 | 2019 | |

| Boston College † | 4 | 1967 | 8 | 2016 | |

| Georgia Tech | 3 | 2006 | 32 | 2019 | |

| Louisville † | 5 | 2019 | 13 | 2019 | |

| Duke | 3 | 1961 | 8 | 2019 | |

| NC State | 2 | 2013 | 31 | 2019 | |

| Notre Dame † | 2 | 2002 | 22 | 2015 | |

| Virginia Tech | 0 | n/a | 10 | 2013 | |

| Pittsburgh | 0 | n/a | 3 | 1995 |

^ Syracuse does not currently field a baseball team but has one appearance in the NCAA baseball tournament prior to joining the conference.

† The count of College World Series appearances includes those made by the school prior to joining the ACC:

- Boston College: 4 appearances

- Florida State: 11 appearances

- Louisville: 3 appearances

- Miami: 21 appearances

- Notre Dame: 2 appearances

- Syracuse: 1 appearance

Field hockey

The ACC has won 20 of the 36 NCAA Championships in field hockey. Maryland won 8 as a member of the ACC.

| School | Total | NCAA Women's Championships |

|---|---|---|

| North Carolina | 8 | 1989, 1995, 1996, 1997, 2007, 2009, 2018, 2019 |

| Wake Forest | 3 | 2002, 2003, 2004 |

| Syracuse | 1 | 2015 |

Golf

Of the current ACC members, 12 sponsor men's golf and 10 sponsor women's golf. Four team national championships in men's golf and seven national titles in women's golf have been won by ACC members while in the conference, led by the Duke women's team that has won seven national titles since 1999. In addition, two more team national titles, one in men's golf and one in women's golf, have been won by current ACC members before they joined the conference.

| School | Men's Team NCAA | Men's Individual NCAA | Women's Team NCAA | Women's Individual NCAA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clemson | 2003 | Charles Warren 1997 | ||

| Duke | 2019, 2014, 2007, 2006, 2005, 2002, 1999 |

Candy Hannemann 2001, Virada Nirapathpongporn 2002, Anna Grzebian 2005, Virginia Elana Carta 2016 | ||

| Georgia Tech | Watts Gunn 1927, Charles Yates 1934, Troy Matteson 2002 |

|||

| Miami | 1984 | Penny Hammel 1983 | ||

| North Carolina | Harvie Ward 1949, John Inman 1984 |

|||

| North Carolina State | Matt Hill 2009 | |||

| Virginia | Dixon Brooke 1940 | |||

| Wake Forest | 1986, 1975, 1974 | Curtis Strange 1974, Jay Haas 1975, Gary Hallberg 1979 |

||

| Notre Dame | 1944 |

- Italics denote championships won before the school joined the ACC.

Lacrosse

Since 1971, when the first men's national champion was determined by the NCAA, the ACC has won 13 NCAA championships, more than any other conference in college lacrosse. Virginia has won seven total national championships, North Carolina has won five, and Duke has won three. Former ACC member Maryland won two national championships as an ACC member. In addition, prior to the establishment of the NCAA tournament, Maryland had won nine national championships while Virginia won two. Syracuse, which joined the ACC in 2013, won ten NCAA-sponsored national championships, the most ever by any Division I lacrosse program, before joining the conference. Since 1987, the only years in which the national championship game did not feature a current ACC member were 2015 and 2017.

Women's lacrosse has only awarded a national championship since 1982, and the ACC has won more titles than any other conference. In all, the ACC has won 14 women's national championships: Maryland has won eleven as an ACC member, Virginia has won three and North Carolina has won two.

| University | Men's NCAA Championships |

Men's NCAA Runner-Up |

Pre-NCAA Men's Championships | Women's NCAA Championships |

Women's NCAA Runner-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virginia | 2019, 2011, 2006, 2003, 1999, 1972 |

1996, 1994, 1986, 1980 |

1970, 1952 | 2004, 1993, 1991 | 2007, 2005, 2003, 1999, 1998, 1996 |

| North Carolina | 2016, 1991, 1986, 1982, 1981 |

1993 | 2016, 2013 | 2009 | |

| Duke | 2014, 2013, 2010 | 2018, 2007, 2005 | |||

| Syracuse | 2009, 2008, 2004, 2002, 2000, 1995, 1993, 1990*, 1989, 1988, 1983 |

2013, 2001, 1999, 1992, 1985, 1984 |

1925, 1924, 1922, 1920 |

2014, 2012 | |

| Notre Dame | 2014, 2010 | ||||

| Boston College | 2019, 2018, 2017 |

Italics denotes championships before it was part of the ACC.

* Syracuse vacated its 1990 championship due to NCAA violations.

Soccer

Twelve of the fifteen ACC schools sponsor men's soccer — a higher proportion than any of the other Power Five conferences. Only the three southernmost ACC schools — Georgia Tech, Florida State, and Miami — do not sponsor soccer. Virginia has won 7 NCAA titles, and more since 1990 than any other university in the country. The ACC overall has won 16 national championships, including 16 of the 31 seasons between 1984 and 2014. Seven by Virginia and the remaining nine by Maryland (3 times), Clemson (twice), North Carolina (twice), Duke, Wake Forest, and Notre Dame.

In women's soccer, North Carolina has won 21 of the 28 NCAA titles since the NCAA crowned its first champion, as well as the only Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW) soccer championship in 1981. The Tar Heels have also won 19 of the 22 ACC tournaments. They lost in the final to North Carolina State in 1988 and Virginia in 2004, both times by penalty kicks. The 2010 tournament was the first in which they failed to make the championship game, falling to eventual champion Wake Forest in the semi-finals. The 2012 ACC tournament saw North Carolina's first quarterfinal loss, to the eventual champion Virginia; however, the Tar Heels went on to win the national title that season. In 2014, Florida State became the first school other than North Carolina to win the national championship as an ACC member. Notre Dame won three NCAA titles before it joined the ACC in 2013.

| School | Men's NCAA Championships | Men's NCAA Runner-Up |

Women's NCAA Championships |

Women's NCAA Runner-Up |

AIAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virginia | 2014, 2009, 1994, 1993, 1992, 1991, 1989 | 1997 | 2014 | ||

| North Carolina | 2011, 2001 | 2008 | 21 [o 1] |

2001, 1998, 1985 | 1981 |

| Clemson | 1987, 1984 | 1979, 2015 | |||

| Notre Dame | 2013 | 1995, 2004, 2010 | 1994, 1996, 1999, 2006, 2008 | ||

| Wake Forest | 2007 | 2016 | |||

| Duke | 1986 | 1995, 1982 | 2011, 1992 | ||

| Florida State | 2014, 2018 | 2007, 2013 | |||

| Louisville | 2010 | ||||

| NC State | 1988 |

- Italics denote championships before the school was part of the ACC.

- North Carolina has won 21 NCAA Championships (2012, 2009, 2008, 2006, 2003, 2000, 1999, 1997, 1996, 1994, 1993, 1992, 1991, 1990, 1989, 1988, 1987, 1986, 1984, 1983, 1982)

Commissioners

| Name | Term |

|---|---|

| Jim Weaver[110] | 1954–1970 |

| Bob James[111] | 1971–1987 |

| Gene Corrigan | 1987–1997 |

| John Swofford[112][113] | 1997–present |

James J. Phillips will become Commissioner in February 2021.[114]

NCAA team championships

The Virginia Cavaliers lead the ACC in NCAA men's titles with 20, while the North Carolina Tar Heels lead in women's titles with 32 and in overall NCAA titles with 45.[115] Excluded from this list are all national championships earned outside the scope of NCAA competition, including Division I FBS football titles, women's AIAW championships, equestrian titles, and retroactive Helms Athletic Foundation titles.

| School | Total | Men | Women | Co-ed | Nickname | Most successful sport (titles) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Carolina | 45 | 13 | 32 | 0 | Tar Heels | Women's soccer (21) |

| Virginia | 27 | 20 | 7 | 0 | Cavaliers | Men's soccer (7) |

| Notre Dame | 19 | 7 | 6 | 6 | Fighting Irish | Fencing (10) |

| Duke | 17 | 9 | 8 | 0 | Blue Devils | Women's golf (7) |

| Syracuse | 15 | 14 | 1 | 0 | Orange | Men's lacrosse (10) |

| Wake Forest | 9 | 6 | 3 | 0 | Demon Deacons | Field hockey, Men's golf (3) |

| Florida State | 9 | 4 | 5 | 0 | Seminoles | Men's gymnastics, Men's outdoor track (2) |

| Boston College | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | Eagles | Men's ice hockey (5) |

| Miami | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | Hurricanes | Baseball (4) |

| Clemson | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Tigers | Men's soccer (2) |

| Louisville | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Cardinals | Men's basketball (3) |

| NC State | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Wolfpack | Men's basketball (2) |

| Georgia Tech | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Yellow Jackets | Women's tennis (1) |

| Pittsburgh | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Panthers | N/A |

| Virginia Tech | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Hokies | N/A |

See also: List of NCAA schools with the most NCAA Division I championships, List of NCAA schools with the most Division I national championships, and NCAA Division I FBS Conferences

Capital One Cup standings

The Capital One Cup is an award given annually to the best men's and women's Division I college athletics programs in the United States. Points are earned throughout the year based on final standings of NCAA Championships and final coaches' poll rankings. Virginia has twice (2015 and 2019) finished first for men's sports, while Notre Dame (2014) has once, and North Carolina (2013) has once finished first on the women's side.

The following table displays ACC top 20 finishes in the Capital One Cup.

See also

- ACC Athlete of the Year

- Atlantic Coast Conference Men's Basketball Player of the Year

- List of Atlantic Coast Conference football champions

- List of Atlantic Coast Conference men's basketball regular season champions

- List of Atlantic Coast Conference business schools

- ACC Women's Basketball regular season

- Atlantic Coast Rugby League

Notes

- It was the second major conference that evolved from the Southern Conference, following the departure of Alabama, Auburn, Florida, Georgia, Georgia Tech, Kentucky, Louisiana State, Mississippi, Mississippi State, Sewanee, Tennessee, Tulane, and Vanderbilt to form the Southeastern Conference.

- The Southern Conference Hall of Fame opened in 2009.[17]

References

- "This Is the ACC". TheACC.com. Archived from the original on December 31, 2010. Retrieved January 8, 2011.

- Schlosser, Jim (June 28, 1998). "Depression Kept Sedgefield from Intended Course". News & Record. p. A1.

- "ACC sets 11-game slate, includes Notre Dame". ESPN.com. July 30, 2020. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "History of FSU Football" (PDF). 2017 Florida State Football Media Guide. p. 153. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 22, 2018. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- "Georgia Tech Football Timeline". 2017 Georgia Tech Football Information Guide. p. 146. Archived from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- Office of Institutional Research (2018). University of Pittsburgh Fact Book 2018 (PDF). University of Pittsburgh. p. 32. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "SEC History". Archived from the original on April 2, 2019.

- "Maryland, Clemson can't play in SC: Terps, Tigers on year probation". Asheville Citizen. December 15, 1951. Archived from the original on April 30, 2019. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- "Founding of the ACC". Archived from the original on May 17, 2013.

- "Seven schools quit SC to form own conference: Tebell says Virginia might join; No state schools in new lineup". Newport News Daily Press. May 9, 1953. Archived from the original on April 30, 2019. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- "Atlantic Coast Conference brings Virginia into fold: Plan to admit West Virginia is turned down; Conference decides to operate as eight-school organization for indefinite period". Petersburg Progress Index. Archived from the original on April 30, 2019. Retrieved April 17, 2019.,

- Watterson, John. "University of Virginia Football 1951–1961: A Perfect Gridiron Storm" (PDF). Journal of Sports History. James Madison University. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 30, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- "ACC Basketball". UNC Press. Archived from the original on December 8, 2011. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- Charles H. Martin, "The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow in Southern College Sports: The Case of the Atlantic Coast Conference." North Carolina Historical Review 76.3 (1999): 253-284. online Archived April 18, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Pamela Grundy, Learning to win: Sports, education, and social change in twentieth-century North Carolina (U of North Carolina Press, 2003) p 297 online Archived December 15, 2018, at the Wayback Machine.

- "ACC Hall of Champions Debuts". SlamOnline.com. Source Interlink Magazines, LLC. March 2, 2011. Archived from the original on March 4, 2011. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- "Southern Conference Announces Inaugural Hall of Fame Class". Southern Conference. January 28, 2009. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- Thamel, Pete (September 17, 2011). "Big East Exit Is Said to Begin for Syracuse and Pittsburgh". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 17, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- Clarke, Liz (September 18, 2011). "ACC expands to 14 with addition of Syracuse, Pittsburgh". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 13, 2012. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- Taylor, John (September 20, 2011). "Big East to force Pitt, Syracuse to stay until 2014". College Football Talk. NBC Sports. Archived from the original on September 25, 2011. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- "SU, BIG EAST Reach Agreement for Orange to Move to ACC in 2013". Syracuse Athletics. July 16, 2012. Archived from the original on July 24, 2012. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- "BIG EAST Conference, University of Pittsburgh Reach Agreement on Pittsburgh Departure From The BIG EAST". Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- Taylor, John (September 12, 2012). "Sources: Notre Dame to ACC". College Football Talk. ESPN. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- McMurphy, Brett (March 12, 2013). "Big East, Notre Dame agree on exit". ESPN. Archived from the original on March 12, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- Prewitt, Alex (November 19, 2012). "Maryland moving to Big Ten". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 19, 2012.

- "ACC snags Louisville as replacement for Maryland". Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- McMurphy, Brett (April 24, 2013). "Media deal OK'd to solidify ACC". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on April 24, 2013. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- Adelson, Andrea (April 22, 2013). "You want stability? Look at the ACC". ACC Blog. ESPN.com. Archived from the original on April 23, 2013. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- McMurphy, Brett (July 19, 2016). "Sources: ACC Network to launch by August 2019". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on July 22, 2016. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

- Somers, D.; Moody, J. (May 21, 2019). "See the Best Colleges Rankings of ACC Schools". US News. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019.

Academically, the ACC boasts the most highly ranked schools across the Power 5 conferences, which compete at the top tier of college athletics, with Duke University leading the way for the conference in a tie at No. 8 in the 2019 U.S. News National Universities rankings.

- Travis, Clay (September 20, 2012). "U.S. News Rankings of Top Six Football Conferences". Outkick The Coverage. Archived from the original on May 7, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- "U.S. News 'Best College' rankings spotlight academic strength of ACC". OrangeAndWhite.com. September 20, 2012. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- Teel, David (September 14, 2011). "Teel Time: Texas, 45th in U.S. News rankings, fits ACC's academic profile". Daily Press. Hampton Roads, Virginia. Archived from the original on March 26, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- Bain, John (September 27, 2011). "College Football Rankings: Best BCS Conferences Based on Academics". Bleacher Report. Archived from the original on October 24, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- "ACC Continues to Lead FBS Conferences in 'Best Colleges' Rankings". theACC.com. September 11, 2019. Archived from the original on October 24, 2019. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- Norlander, Matt (June 19, 2013). "Study: How and why the APR is improving major-program academics". CBSSports.com. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- Young, Jim (June 12, 2013). "Analyzing The ACC's APR". ACC Sports Journal. Archived from the original on June 16, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- "U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year (FY) 2018 Endowment Market Value and Change* in Endowment Market Value from FY17 to FY18" (PDF). National Association of College and University Business Officers and Commonfund Institute. January 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 29, 2019. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- Lombardi, John V.; Capaldi Phillips, Elizabeth D.; Abbey, Craig W.; Craig, Diane D. (2017). The Top American Research Universities 2016 Annual Report (PDF). The Center for Measuring University Performance. pp. 206–209. ISBN 9780985617066. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 16, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

Faculty Awards in the Arts, Humanities, Science, Engineering, and Health Source: Directories or web-based listings for multiple agencies or organizations. For this category, we collect data from several prominent grant and fellowship programs in the arts, humanities, science, engineering, and health fields. (see pages 227-228)

- "The Princeton Review's College Ratings". The Princeton Review. Archived from the original on March 25, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "2018 Best Colleges National University Rankings". US News & World Report. September 11, 2017. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "2017 College Guide and Rankings". Washington Monthly. 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2017". ShanghaiRanking Consultancy. August 15, 2017. Archived from the original on January 19, 2019. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "2017 - Overall Ranking : Top Universities in USA". National Taiwan University. October 10, 2017. Archived from the original on April 8, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "CWTS Leiden Ranking 2017". Netherlands: Centre for Science and Technology Studies, Leiden University. 2017. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "SCIMAGO Institutions Ranking". Scimago Lab. 2017. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "University Ranking by Academic Performance – United States of America". URAP Research Laboratory, Middle East Technical University. October 30, 2017. Archived from the original on April 8, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "QS World University Rankings 2018". Quacquarelli Symonds. June 8, 2017. Archived from the original on June 9, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- McKindra, Leilana (March 13, 2006). "ACC takes worldwide approach to academic programs". The NCAA News. Archived from the original on August 22, 2012. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- Yanda, Steve (July 14, 2008). "ACC's Forward Progress Limited; Expanded Conference Rates Mixed Reviews at 5-Year Mark". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- Brown, David G. (2009). "About the ACCIAC". Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- Brown, David G. (2009). "MOM: Meeting of the Minds Conferences". Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- Brown, David G. (2009). "Student Leadership Conference". Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- Brown, David G. (2009). "Creativity & Innovation Fellowships". Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- Brown, David G. (2013). "Summer Research Scholars". Archived from the original on September 2, 2014. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- "Second Annual ACC Debate Championship Set for April 15–17". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 2016. Archived from the original on April 19, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- "ACC Inventure Prize". Georgia Tech University. 2016. Archived from the original on April 12, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- Brown, David G. (2015). "Other Collaborative Initiatives". Archived from the original on April 22, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- Brown, David G. (2015). "Distinguished Lecturers". acciac.org. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- Inaugural ACC Student President Conference (YouTube video). Pitt Student Affairs. September 12, 2013. Archived from the original on June 17, 2014. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- Brown, David G. (2009). "Coach for College". Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- Brown, David G. (2009). "Other Collaborative Initiatives". Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- Brown, David G. (2013). "Student Study Abroad Scholarships". Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- Brown, David G. (2009). "Other Groups and Committees". Archived from the original on May 14, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- "NCAA FINANCES". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 30, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- "James T. Valvano Arena at William Neal Reynolds Coliseum". Facilities. NC State University Athletics. Archived from the original on March 7, 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ACC (October 30, 2015). "Official Athletics Site". ACC. Archived from the original on June 16, 2006. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- "Fencing Back In ACC Mix" (Press release). Atlantic Coast Conference. September 27, 2013. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- Gutierrez, Matthew (February 21, 2017). "Despite rich history, Syracuse baseball is unlikely in near future". The Daily Orange. Syracuse, NY. Archived from the original on February 9, 2018. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- "Clemson to Discontinue Men's Track and Field and Cross Country Program" (Press release). Clemson Tigers. November 5, 2020. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- "Virginia Adds Men's and Women's Squash as Varsity Sports". Archived from the original on October 31, 2018. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- Meyer, Craig (November 1, 2018). "Pitt will add a women's lacrosse program starting in 2021-22". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on November 5, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- "TFRRS | ACC Cross Country Championships Track & Field Meet Results". www.tfrrs.org. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- "2019 ACC Field Hockey Bracket (PDF) - Atlantic Coast Conference" (PDF). theacc.com. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- "Virginia vs. Clemson - Game Summary - December 7, 2019 - ESPN". ESPN.com. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- "2019 ACC Men's Soccer Championship Bracket (PDF) - Atlantic Coast Conference" (PDF). theacc.com. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- "WSOC_Champ_Bracket19 (PDF) - Atlantic Coast Conference" (PDF). theacc.com. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- "2019-20 ACC Women's Basketball Tournament - Atlantic Coast Conference". May 14, 2020. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- "2020 ACC Fencing Championships Results - Team". escrimeresults.com. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- "NC State Wins 2020 ACC Men's Swimming and Diving Championship". theacc.com. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- "Virginia Wins 2020 ACC Women's Swimming & Diving Championship". theacc.com. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- "Team Scores". flashresults.com. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- "ACC Wrestling Championship Brackets (PDF) - Atlantic Coast Conference" (PDF). theacc.com. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- "Division I-A All-Time Wins". College Football Data Warehouse. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved July 2, 2013.

- NCAA College Football Standings Archived July 25, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Accessed March 3, 2010

- Chip Patterson (December 20, 2013). "Notre Dame sets ACC schedule for 2014-16". CBSSports.com. Archived from the original on April 28, 2014. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- "ACC Unveils Future League Seal, Divisional Names" (Press release). Atlantic Coast Conference. October 18, 2004. Archived from the original on May 25, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- "ACC sticks with 8-game schedule". espn. October 2, 2012. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

- McMurphy, Brett (January 29, 2015). "ACC: BYU to count as Power 5 team". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on February 3, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- Adelson, Andrea (January 26, 2015). "UNC, Wake agree to non-ACC series". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on February 4, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- "ACC Announces Bowl Agreements for 2020-25".

- "Bowl Selection Process". SECSports.com.

- "ACC finalizes bowl lineup for 2014 through 2019". Card Chronicle. August 8, 2013. Archived from the original on July 11, 2015. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- "Pac-12 Conference – 2014 Football Media Guide". Catalog.e-digitaleditions.com. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- "ACC Announces Bowl Agreements for 2020-25".

- 2011 NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision Records (PDF). Indianapolis: The National Collegiate Athletic Association. August 2011. pp. 70–75. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- Jenkins, Dan (September 11, 1967). "This Year The Fight Will Be In The Open". Sports Illustrated. Chicago: Time, Inc. 27 (11): 30–33. Archived from the original on June 2, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- Borghetti, E.J.; Nestor, Mendy; Welsh, Celeste, eds. (2008). 2008 Pitt Football Media Guide (PDF). Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh. p. 156. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 23, 2011. Retrieved July 7, 2010.

- 2012 NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision Records (PDF). Indianapolis, IN: The National Collegiate Athletic Association. August 2012. pp. 71–73. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 4, 2018. Retrieved December 28, 2012.

- "Pittsburgh Recognized National Championships". College Football Data Warehouse. Archived from the original on August 19, 2016.

- "Pittsburgh Total National Championships". College Football Data Warehouse. Archived from the original on November 5, 2016.

- "March Madness Swells as NCAA Pumps Up NIT Tournament". Bloomberg. March 14, 2006. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- The Triangle teams' original partners, which have since been varied (for example, Duke's original partners were North Carolina and Maryland and, as reflected in the table in the body of the article, are now North Carolina and Wake Forest) can be found here: http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/sports/college/mensbasketball/acc/2005-02-25-12-team-schedule_x.htm Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- "ACC Announces Future Regular-Season Scheduling Formats". Atlantic Coast Conference. February 3, 2012. Archived from the original on May 19, 2012. Retrieved February 7, 2012.

- Katz, Andy (October 4, 2012). "Expanding ACC sets primary partners". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- Free, Bill (February 9, 1999). "This overtime lasts 25 years; N.C. State-Terps: The 1974 ACC tourney final remains a fresh memory for players of both teams. After all, the classic decided a national title". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2017.