Atlantic tarpon

The Atlantic tarpon (Megalops atlanticus) is a ray-finned fish that inhabits coastal waters, estuaries, lagoons, and rivers. It is also known as the silver king. It is found in the Atlantic Ocean, typically in tropical and subtropical regions, though it has been reported as far north as Nova Scotia and the Atlantic coast of southern France, and as far south as Argentina. As with all Elopiformes, it spawns at sea. Its diet includes small fish and crustaceans.[5]

| Atlantic tarpon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Elopiformes |

| Family: | Megalopidae |

| Genus: | Megalops |

| Species: | M. atlanticus |

| Binomial name | |

| Megalops atlanticus Valenciennes, 1847 | |

| Synonyms[3][4] | |

| |

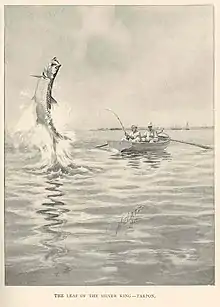

The tarpon has a reputation for great aerobatics, attaining astonishing size, and having impressive armored scales. It is poorly received as food, but valued as a game fish.

Description

Atlantic tarpon evolved approximately 18 million years ago and are one of the oldest living fish.[6]

It has been recorded at up to 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) in length and weighing up to 161 kg (355 lb).[7] Males rarely weight more than 100 pounds.[6]

A tarpon is capable of filling its swim bladder with air, like a primitive lung. This gives it a predatory advantage when oxygen levels in the water are low. In appearance, it is greenish or bluish on top and silver on the sides. The large mouth is turned upwards and the lower jaw contains an elongated, bony plate. The last ray of the dorsal fin is much longer than the others, reaching nearly to the tail.[6]

Behavior

The Atlantic tarpon's most significant predators are sharks and humans.[7]

Relationship with humans

The scales of Atlantic tarpon have been used as nail files and for decorative purposes since pre-history. Their crushed up scales also feature in traditional medicine, particularly in Brazil.[8]

The Atlantic tarpon was first described scientifically by zoologist Achille Valenciennes in 1847 as Megalops atlanticus, Megalops being inspired by their large eyes.[6]

The tarpon is the official state saltwater fish of Alabama.[9][10]

Atlantic tarpon adapt well to urban and suburban environments due to their tolerance for boat traffic and low water quality. Around humans Atlantic tarpon are primarily nocturnal.[11]

While the Atlantic tarpon is rarely consumed in the United States subsistence and commercial fisheries exist in a number of countries.[7]

Game fishing

Tarpons are considered one of the great saltwater game fishes, not only because of their size and their accessible haunts, but also because of their fighting spirit when hooked; they are very strong, making spectacular leaps into the air. They are the largest species targeted by fly fishermen in shallow water.[12] The flesh is undesirable, commonly described as being smelly and bony. In Florida and Alabama, a special permit is required to kill and keep a tarpon, so most tarpon fishing there is catch and release.

The International Sábalo (tarpon) Fishing Tournament is held every May in Tecolutla on Mexico's Costa Esmeralda.

Tarpon are known by English speaking anglers as “The Silver King."[13]

Geographical distribution and migration

Since tarpons are not commercially valuable as a food fish, very little has been documented concerning their geographical distribution and migrations. They inhabit both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Their range in the eastern Atlantic has been reliably established from Senegal to the Congo. Tarpons inhabiting the western Atlantic are principally found to populate warmer coastal waters primarily in the Gulf of Mexico, Florida, and the West Indies. Nonetheless, they are regularly caught by anglers at Cape Hatteras and as far as Nova Scotia, Bermuda, and south to Argentina.[14]

Atlantic tarpon are highly migratory and often cross international boundaries. This introduces challenges in management and conservation.[7]

Scientific studies indicate schools have routinely migrated through the Panama Canal from the Atlantic to the Pacific and back for over 80 years.[15][14] They have not been shown to breed in the Pacific Ocean, but anecdotal evidence by tarpon fishing guides and anglers indicates it is possible, as over the last 60 years, many small juveniles and some mature giants have been caught and documented, principally on the Pacific side of Panama at the Bayano River, in the Gulf of San Miguel and its tributaries, Coiba Island in the Gulf of Chiriquí, and at Piñas Bay in the Gulf of Panama. Since tarpons tolerate a wide range of salinity and are opportunistic feeders, their migrations are limited only by water temperatures. They prefer water temperatures of 22 to 28 °C (72 to 82 °F); below 16 °C (61 °F) they become inactive, and temperatures under 4 °C (39 °F) can be lethal. A large non-migrant tarpon community is found in the Rio San Juan and Lake Nicaragua.

Atlantic tarpon breed in spawning aggregations in the open ocean, Atlantic tarpon share a unique larval stage known as a leptocephalus with bonefish, ladyfish, and eels. Unlike the larvae of other fish these larvae do not eat as their long slender bodies have very low energy requirements. While larvae the Atlantic tarpon's teeth grow pointed forward to keep debris out of their mouth. The leptocephali develop into juveniles which make their way inshore, often into stagnant water with a very low oxygen content which can't be tolerated by most of their predators. When they are about three years old Atlantic tarpon migrate from these backwater habitats to a variety of nearshore ones, growing rapidly but primarily in length as opposed to girth. At around eight years of age an Atlantic tarpon reaches its sexual maturity and begins to gain length as well as girth. Growth rates also diverge at this point with males growing much slower than females. Sexually mature Atlantic tarpon will begin migrating to join spawning aggregations.[6]

See also

References

- "†Megalops atlanticus Valenciennes 1847 (ray-finned fish)". PBDB.

- Adams, A.; Guindon, K.; Horodysky, A.; MacDonald, T.; McBride, R.; Shenker, J. & Ward, R. (2012). "Megalops atlanticus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012: e.T191823A2006676. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012.RLTS.T191823A2006676.en.

- "Megalopidae" (PDF). Deeplyfish- fishes of the world. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- Froese, R.; Pauly, D. (2017). "Megalopidae". FishBase version (02/2017). Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2005). "Megalops atlanticus" in FishBase. 05 2005 version.

- Larkin, Michael. "The Science Behind Tarpon". www.saltwatersportsman.com. Salt Water Sportsman. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- Udel, Diana. "New study reveals international movements of Atlantic Tarpon, need for protection". news.miami.edu. University of Miami. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- Tomalin, Terry. "Tarpon remain a fascinating species". www.tampabay.com. Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- "Official Alabama Saltwater Fish". Alabama Emblems, Symbols and Honors. Alabama Department of Archives & History. 2006-04-27. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- Kirkland, Walter. "Tarpon Fishing Grounds in Alabama". www.sportfishingmag.com. Sport Fishing Magazine. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- Conner, Mike. "Urban Tarpon on Fly". www.saltwatersportsman.com. Saltwater Sportsman. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- Burke, Monte. "A Crappy Boat Ride, a Record Catch and a Fly-Fishing Frenzy". www.si.com. Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- Graves, Russell A. "Texas Tarpon: The Mighty Silver King". www.texas-wildlife.org. Texas Wildlife Association. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- Castellanos-Galindo, Gustavo A.; et al. (2019). "Atlantic Tarpon in the Tropical Eastern Pacific 80 years after it first crossed the Panama Canal". Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries. 29: 401–416. doi:10.1007/s11160-019-09565-z.

- Hildebrand, Samuel F. (1939). "The Panama Canal as a Passageway for Fishes, with Lists and Remarks on the Fishes and Invertebrates Observed". Zoologica. 24: 15–45.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Megalops atlanticus. |

- Save the Tarpon

- Bonefish and Tarpon Conservation Research

- Photos of Atlantic tarpon on Sealife Collection