Axolotl

The axolotl (/ˈæksəlɒtəl/; from Classical Nahuatl: āxōlōtl [aːˈʃoːloːtɬ] (![]() listen)), Ambystoma mexicanum,[2] also known as the Mexican walking fish, is a neotenic salamander related to the tiger salamander.[2][3][4] Although colloquially known as a "walking fish",[3][4] the axolotl is not a fish but an amphibian.[2] The species was originally found in several lakes, such as Lake Xochimilco underlying Mexico City.[1] Axolotls are unusual among amphibians in that they reach adulthood without undergoing metamorphosis. Instead of taking to the land, adults remain aquatic and gilled.

listen)), Ambystoma mexicanum,[2] also known as the Mexican walking fish, is a neotenic salamander related to the tiger salamander.[2][3][4] Although colloquially known as a "walking fish",[3][4] the axolotl is not a fish but an amphibian.[2] The species was originally found in several lakes, such as Lake Xochimilco underlying Mexico City.[1] Axolotls are unusual among amphibians in that they reach adulthood without undergoing metamorphosis. Instead of taking to the land, adults remain aquatic and gilled.

| Axolotl | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Urodela |

| Family: | Ambystomatidae |

| Genus: | Ambystoma |

| Species: | A. mexicanum |

| Binomial name | |

| Ambystoma mexicanum | |

| |

| Its distribution is marked in red. | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Axolotls should not be confused with waterdogs, the larval stage of the closely related tiger salamanders (A. tigrinum and A. mavortium), which are widespread in much of North America and occasionally become neotenic. Neither should they be confused with mudpuppies (Necturus spp.), fully aquatic salamanders from a different family that are not closely related to the axolotl but bear a superficial resemblance.[5]

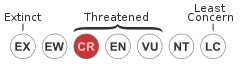

As of 2010, wild axolotls were near extinction[6] due to urbanization in Mexico City and consequent water pollution, as well as the introduction of invasive species such as tilapia and perch. They are listed as critically endangered in the wild, with a decreasing population, by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) and as an endangered species by the IUCN's CITES treaty. Axolotls are used extensively in scientific research due to their ability to regenerate limbs.[7] Axolotls were also sold as food in Mexican markets and were a staple in the Aztec diet.[8]

Surveys in 1998, 2003, and 2008 found 6,000, 1,000, and 100 axolotls per square kilometer in its Lake Xochimilco habitat, respectively.[9] A four-month-long search in 2013, however, turned up no surviving individuals in the wild. Just a month later, two wild ones were spotted in a network of canals leading from Xochimilco.[10] The city is working on conserving axolotls by building "axolotl shelters" and conserving remaining and potential habitats for the salamanders.

Description

A sexually mature adult axolotl, at age 18–24 months, ranges in length from 15 to 45 cm (6 to 18 in), although a size close to 23 cm (9 in) is most common and greater than 30 cm (12 in) is rare. Axolotls possess features typical of salamander larvae, including external gills and a caudal fin extending from behind the head to the vent.[11]

Their heads are wide, and their eyes are lidless. Their limbs are underdeveloped and possess long, thin digits. Males are identified by their swollen cloacae lined with papillae, while females are noticeable for their wider bodies full of eggs. Three pairs of external gill stalks (rami) originate behind their heads and are used to move oxygenated water. The external gill rami are lined with filaments (fimbriae) to increase surface area for gas exchange. Four gill slits lined with gill rakers are hidden underneath the external gills.

Axolotls have barely visible vestigial teeth, which would have developed during metamorphosis. The primary method of feeding is by suction, during which their rakers interlock to close the gill slits. External gills are used for respiration, although buccal pumping (gulping air from the surface) may also be used to provide oxygen to their lungs.

Axolotls have four pigmentation genes; when mutated they create different color variants. The normal wild type animal is brown/tan with gold speckles and an olive undertone. The four mutant colors are leucistic (pale pink with black eyes), albino (golden with gold eyes), axanthic (grey with black eyes) and melanoid (all black with no gold speckling or olive tone). In addition, there is wide individual variability in the size, frequency, and intensity of the gold speckling and at least one variant that develops a black and white piebald appearance on reaching maturity. Because pet breeders frequently cross the variant colors, animals that are double recessive mutants are common in the pet trade, especially white/pink animals with pink eyes that are double homozygous mutants for both the albino and leucistic trait.[12] Axolotls also have some limited ability to alter their color to provide better camouflage by changing the relative size and thickness of their melanophores.[13]

Habitat and ecology

The axolotl is only native to Lake Xochimilco and Lake Chalco in the Valley of Mexico. Lake Chalco no longer exists, having been drained as a flood control measure, and Lake Xochimilco remains a remnant of its former self, existing mainly as canals. The water temperature in Xochimilco rarely rises above 20 °C (68 °F), though it may fall to 6 to 7 °C in the winter, and perhaps lower.

The wild population has been put under heavy pressure by the growth of Mexico City. The axolotl is currently on the International Union for Conservation of Nature's annual Red List of threatened species. Non-native fish, such as African tilapia and Asian carp, have also recently been introduced to the waters. These new fish have been eating the axolotls' young, as well as its primary source of food.[14]

Axolotls are members of the tiger salamander, or Ambystoma tigrinum, species complex, along with all other Mexican species of Ambystoma. Their habitat is like that of most neotenic species—a high altitude body of water surrounded by a risky terrestrial environment. These conditions are thought to favor neoteny. However, a terrestrial population of Mexican tiger salamanders occupies and breeds in the axolotl's habitat.

The axolotl is carnivorous, consuming small prey such as worms, insects, and small fish in the wild. Axolotls locate food by smell, and will "snap" at any potential meal, sucking the food into their stomachs with vacuum force.[15]

Neoteny

Axolotls exhibit neoteny, meaning that they reach sexual maturity without undergoing metamorphosis.[16] Many species within the axolotl's genus are either entirely neotenic or have neotenic populations. In the axolotl, metamorphic failure is caused by a lack of thyroid stimulating hormone, which is used to induce the thyroid to produce thyroxine in transforming salamanders. The genes responsible for neoteny in laboratory animals may have been identified; however, they are not linked in wild populations, suggesting artificial selection is the cause of complete neoteny in laboratory and pet axolotls.

Neoteny has been observed in all salamander families in which it seems to be a survival mechanism, in aquatic environments only of mountain and hill, with little food and, in particular, with little iodine. In this way, salamanders can reproduce and survive in the form of a smaller larval stage, which is aquatic and requires a lower quality and quantity of food compared to the big adult, which is terrestrial. If the salamander larvae ingest a sufficient amount of iodine, directly or indirectly through cannibalism, they quickly begin metamorphosis and transform into bigger terrestrial adults, with higher dietary requirements.[17] In fact, in some high mountain lakes there live dwarf forms of salmonids that are caused by deficiencies in food and, in particular, iodine, which causes cretinism and dwarfism due to hypothyroidism, as it does in humans.

Unlike some other neotenic salamanders (sirens and Necturus), axolotls can be induced to metamorphose by an injection of iodine (used in the production of thyroid hormones) or by shots of thyroxine hormone. The adult form resembles a terrestrial plateau tiger salamander, but has several differences, such as longer toes, which support its status as a separate species.

Use as a model organism

Six adult axolotls (including a leucistic specimen) were shipped from Mexico City to the Jardin des Plantes in Paris in 1863. Unaware of their neoteny, Auguste Duméril was surprised when, instead of the axolotl, he found in the vivarium a new species, similar to the salamander.[18] This discovery was the starting point of research about neoteny. It is not certain that Ambystoma velasci specimens were not included in the original shipment.

Vilem Laufberger in Prague used thyroid hormone injections to induce an axolotl to grow into a terrestrial adult salamander. The experiment was repeated by Englishman Julian Huxley, who was unaware the experiment had already been done, using ground thyroids.[19] Since then, experiments have been done often with injections of iodine or various thyroid hormones used to induce metamorphosis.

Today, the axolotl is still used in research as a model organism, and large numbers are bred in captivity. They are especially easy to breed compared to other salamanders in their family, which are almost never captive-bred due to the demands of terrestrial life. One attractive feature for research is the large and easily manipulated embryo, which allows viewing of the full development of a vertebrate. Axolotls are used in heart defect studies due to the presence of a mutant gene that causes heart failure in embryos. Since the embryos survive almost to hatching with no heart function, the defect is very observable. The axolotl is also considered an ideal animal model for the study of neural tube closure due to the similarities between human and axolotl neural plate and tube formation; the axolotl's neural tube, unlike the frog's, is not hidden under a layer of superficial epithelium.[20] There are also mutations affecting other organ systems some of which are not well characterized and others that are.[21] The genetics of the color variants of the axolotl have also been widely studied.[12]

Regeneration

The feature of the salamander that attracts most attention is its healing ability: the axolotl does not heal by scarring and is capable of the regeneration of entire lost appendages in a period of months, and, in certain cases, more vital structures, such as tail, limb, central nervous system, and tissues of the eye and heart.[22] Some have indeed been found restoring the less vital parts of their brains. They can also readily accept transplants from other individuals, including eyes and parts of the brain—restoring these alien organs to full functionality. In some cases, axolotls have been known to repair a damaged limb, as well as regenerating an additional one, ending up with an extra appendage that makes them attractive to pet owners as a novelty. In metamorphosed individuals, however, the ability to regenerate is greatly diminished. The axolotl is therefore used as a model for the development of limbs in vertebrates.[23]

It is believed that during limb generation, axolotls have a different system to regulate their internal macrophage level and suppress inflammation, as scarring prevents proper healing and regeneration.[24] However, this belief has been questioned by other studies.[25]

Genome

The 32 billion base pair long sequence of the axolotl's genome was published in 2018 and is the largest animal genome completed so far. It revealed species-specific genetic pathways that may be responsible for limb regeneration.[26] Although the axolotl genome is about 10 times as large as the human genome, it encodes a similar number of proteins, namely 23,251[26] (the human genome encodes about 20,000 proteins). The size difference is mostly explained by a large fraction of repetitive sequences, but such repeated elements also contribute to increased median intron sizes (22,759 bp) which are 13, 16 and 25 times that observed in human (1,750 bp), mouse (1,469 bp) and Tibetan frog (906 bp), respectively.[26]

Captive care

The axolotl is a popular exotic pet like its relative, the tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigerinum). As for all poikilothermic organisms, lower temperatures result in slower metabolism and a very unhealthily reduced appetite. Temperatures at approximately 16 °C (61 °F) to 18 °C (64 °F) are suggested for captive axolotls to ensure sufficient food intake; stress resulting from more than a day's exposure to lower temperatures may quickly lead to disease and death, and temperatures higher than 24 °C (75 °F) may lead to metabolic rate increase, also causing stress and eventually death.[27][28] Chlorine, commonly added to tapwater, is harmful to axolotls. A single axolotl typically requires a 40-litre (11-US-gallon) tank with a water depth of at least 15 cm (6 in). Axolotls spend the majority of the time at the bottom of the tank.

Salts, such as Holtfreter's solution, are usually added to the water to prevent infection.[30]

In captivity, axolotls eat a variety of readily available foods, including trout and salmon pellets, frozen or live bloodworms, earthworms, and waxworms. Axolotls can also eat feeder fish, but care should be taken as fish may contain parasites.[31]

Substrates are another important consideration for captive axolotls, as axolotls (like other amphibians and reptiles) tend to ingest bedding material together with food[32] and are commonly prone to gastrointestinal obstruction and foreign body ingestion.[33] Some common substrates used for animal enclosures can be harmful for amphibians and reptiles. If gravel (common in aquarium use) is used, it is recommended that it consist of smooth particles of a size small enough to pass through the digestive tract.[32] One guide to axolotl care for laboratories notes that bowel obstructions are a common cause of death, and recommends that no items with a diameter below 3 cm should be available to the animal.[34]

There is some evidence that axolotls might seek out appropriately-sized gravel for use as gastroliths[35] based on experiments conducted at the University of Manitoba axolotl colony.[36][37]

In popular culture

Axolotl is one of a number of words, mostly of foreign origin, adopted by Mad Magazine as nonsense words for use as running gags; potrzebie and veeblefetzer are two others. These achieved some popularity with readers of the magazine; see for example the discussion of a poem (quoted in full) centering on the word.[38]

The axolotl's real world ability to regrow limbs served as the inspiration for the Tleilaxu axlotl tanks in the fictional Dune universe created by Frank Herbert.

Argentine writer Julio Cortázar included a short story entitled "Axolotl" in his 1956 collection Final del juego. The story concerns a man who becomes obsessed with the salamanders after viewing them in an aquarium in Paris.[39]

In the Netflix series Bojack Horseman, there is an anthropomorphic axolotl character named Yolanda Buenaventura voiced by Natalie Morales.[40]

The Netherlands-based contemporary art music ensemble Axolot takes "their name from the ancient yet futuristic evolutionary wonder the axolotl, the ensemble takes the concept of a 'recorder trio' to its limits."[41]

In 2020 it was announced that the axolotl will be featured on the new design for Mexico's 50-peso banknote, along with images of maize and chinampas. The banknotes are expected to go into circulation by 2022.[42]

At Minecraft Live 2020, Mojang Studios announced that axolotls will be added to the sandbox game Minecraft in its next major update, 1.17 (planned to release in the summer of 2021).[43]

See also

References

- Luis Zambrano; Paola Mosig Reidl; Jeanne McKay; Richard Griffiths; Brad Shaffer; Oscar Flores-Villela; Gabriela Parra-Olea; David Wake (2010). "Ambystoma mexicanum". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010: e.T1095A3229615. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-2.RLTS.T1095A3229615.en. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- Frost, Darrel R. (2018). "Ambystoma mexicanum (Shaw and Nodder, 1798)". Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference. Version 6.0. American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- "Mexican Walking Fish, Axolotls Ambystoma mexicanum" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 March 2018.

- "Axolotols (Walking Fish)". Aquarium Online. Archived from the original on 10 April 2013. Retrieved 2013-09-12.

- Malacinski, George M. (Spring 1978). "The Mexican Axolotl, Ambystoma mexicanum: Its Biology and Developmental Genetics, and Its Autonomous Cell-Lethal Genes". American Zoologist. 18 (2): 195–206. doi:10.1093/icb/18.2.195.

- Matt Walker (2009-08-26). "Axolotl verges on wild extinction". BBC. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Weird Creatures with Nick Baker (Television series). Dartmoor, England, UK: The Science Channel. 2009-11-11. Event occurs at 00:25.

- "Mythic Salamander Faces Crucial Test: Survival in the Wild". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- Stevenson, M. (2014-01-28). "Mexico's 'water monster' may have disappeared". SFGate.com. Associated Press. Retrieved 2014-01-29.

- "Endangered 'water monster' Axolotl found in Mexico City lake". The Independent. 2014-02-24. Retrieved 2017-06-02.

- San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, California) 7 August 1887, page 9, authored by Yda Addis

- Frost, Sally K.; Briggs, Fran; Malacinski, George M. (1984). "A color atlas of pigment genes in the Mexican axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum)". Differentiation. 26 (1–3): 182–188. doi:10.1111/j.1432-0436.1984.tb01393.x.

- Pietsch, Paul; Schneider, Carl W. (1985). "Vision and the skin camouflage reactions of Ambystoma larvae: the effects of eye transplants and brain lesions". Brain Research. 340 (1): 37–60. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(85)90772-3. PMID 4027646. S2CID 22723238.

- "Mexico City's 'water monster' nears extinction". November 2008. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Wainwright, P. C.; Sanford, C. P.; Reilly, S. M.; Lauder, G. V. (1989). "Evolution of motor patterns: aquatic feeding in salamanders and ray-finned fishes". Brain, Behavior and Evolution. 34 (6): 329–341. doi:10.1159/000116519. PMID 2611639.

- Ley, Willy (February 1968). "Epitaph for a Lonely Olm". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 95–104.

- Venturi, S. (2004). "Iodine and Evolution. DIMI-Marche". Archived from the original on 4 March 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- Duméril, Auguste (1866). "Observations faites a la ménagerie des reptiles du muséum d'histoire naturelle sur la reproduction des axolotls, batraciens urodèles a branchies extérieures, et sur les metamorphoses qu'ils y ont subies". Bulletin de la Société Impériale Zoologique d'Acclimatation. 2. 3: 79–89.

- Reiß, Christian; Olsson, Lennart; Hoßfeld, Uwe (July 2015). "The history of the oldest self-sustaining laboratory animal: 150 years of axolotl research". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 324 (5): 393–404. doi:10.1002/jez.b.22617. PMID 25920413.

- Gordon, R. (1985). "A review of the theories of vertebrate neurulation and their relationship to the mechanics of neural tube birth defects". Journal of Embryology and Experimental Morphology. 89 (Supplement): 229–255. PMID 3913733.

- Armstrong, John B. (1985). "The axolotl mutants". Developmental Genetics. 6 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1002/dvg.1020060102.

- Caballero-Pérez, Juan; Espinal-Centeno, Annie; Falcon, Francisco; García-Ortega, Luis F.; Curiel-Quesada, Everardo; Cruz-Hernández, Andrés; Bako, Laszlo; Chen, Xuemei; Martínez, Octavio; Alberto Arteaga-Vázquez, Mario; Herrera-Estrella, Luis (January 2018). "Transcriptional landscapes of Axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum)". Developmental Biology. 433 (2): 227–239. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.08.022. PMID 29291975.

- Roy, S; Gatien, S (November 2008). "Regeneration in axolotls: a model to aim for!". Experimental Gerontology. 43 (11): 968–73. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2008.09.003. PMID 18814845. S2CID 31199048.

- Goodwin, James W.; Pinto, Alexander R.; Rosenthal, Nadia A. (June 4, 2013). Olson, Eric N. (ed.). "Macrophages are required for adult salamander limb regeneration". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (23). doi:10.1073/pnas.1300290110. Retrieved December 12, 2020 – via PNAS.org.

- Pedersen, Katherine; Rasmussen, Rikke Kongsgaard; Dittrich, Anita; Pedersen, Michael; Lauridsen, Henrik (April 17, 2020). "Modulating the immune response and the pericardial environment with LPS or prednisolone in the axolotl does not change the regenerative capacity of cryoinjured hearts". The FASEB Journal. 34 (S1). doi:10.1096/fasebj.2020.34.s1.04015. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- Nowoshilow, Sergej; Schloissnig, Siegfried; Fei, Ji-Feng; Dahl, Andreas; Pang, Andy W. C.; Pippel, Martin; Winkler, Sylke; Hastie, Alex R.; Young, George (2018-01-24). "The axolotl genome and the evolution of key tissue formation regulators". Nature. 554 (7690): 50–55. Bibcode:2018Natur.554...50N. doi:10.1038/nature25458. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 29364872.

- "Axolotls – Requirements & Water Conditions in Captivity". axolotl.org. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- "Caudata Culture Species Entry – Ambystoma mexicanum – Axolotl". www.caudata.org. Retrieved 2016-03-14.

- Kulbisky, Gordon P; Rickey, Daniel W; Reed, Martin H; Björklund, Natalie; Gordon, Richard (1999). "The axolotl as an animal model for the comparison of 3-D ultrasound with plain film radiography". Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology. 25 (6): 969–975. doi:10.1016/s0301-5629(99)00040-x. PMID 10461726.

- Clare, John P. "Health and Diseases". axolotl.org.

- Strecker, Angela L.; Campbell, Philip M.; Olden, Julian D. (2011). "The Aquarium Trade as an Invasion Pathway in the Pacific Northwest". Fisheries. 36 (2): 74–85. doi:10.1577/03632415.2011.10389070.

- Pough, F. H. (1992). "Recommendations for the Care of Amphibians and Reptiles in Academic Institutions". Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

- Clayton, Leigh Ann; Gore, Stacey R. (2007). "Amphibian Emergency Medicine". Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice. 10 (2): 587–620. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2007.02.004. PMID 17577564.

- Gresens, Jill (2004). "An Introduction to the Mexican Axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum)". Lab Animal. 33 (9): 41–47. doi:10.1038/laban1004-41. PMID 15457201. S2CID 33299160.

- Wings, O A review of gastrolith function with implications for fossil vertebrates and a revised classification Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 52 (1): 1–16

- Gordon, N, Gastroliths – How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Gravel.

- Björklund, N.K. (1993). Small is beautiful: economical axolotl colony maintenance with natural spawnings as if axolotls mattered. In: Handbook on Practical Methods. Ed.: G.M. Malacinski & S.T. Duhon. Bloomington, Department of Biology, Indiana University: 38–47.

- "Axolotl poetry". Caudata.org, the Newt & Salamander Information Portal.

From MAD magazine #43, 1958: I Wandered Lonely as a Clod

- ""Axolotl" by Julio Cortazar". southerncrossreview.org. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- "A 'BoJack Horseman' Character Officially Came Out as Asexual, and That's Important". Hornet. 2017-09-11. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- booklet for compact disc, "Constellations: minimal music for recorders" by Sarah Jeffrey and Trio Axolot, SAMCD044 (2018)

- "Mexican axolotl will be the new image of the 50 peso bill". The Yucatan Times. 2020-02-21. Retrieved 2020-03-04.

- "Minecraft Live The Recap". Minecraft.net. 2020-10-03. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ambystoma mexicanum. |

- Ambystomatidae at Curlie

- Follow the Eggs, Hatchlings and Juveniles

- Mating Dance and Laying Eggs

- Follow the Eggs and Hatchlings (2nd Batch)

- Indiana U Axolotl Colony

- University of KY Axolotl Colony

- Mystical amphibian venerated by Aztecs nears extinction

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 20 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 63.

- "The Tao of Axolotl" – thetolteciching.com; on folklore