Tilapia

Tilapia (/tɪˈlɑːpiə/ tih-LAH-pee-ə) is the common name for nearly a hundred species of cichlid fish from the coelotilapine, coptodonine, heterotilapine, oreochromine, pelmatolapiine and tilapiine tribes (formerly all were "Tilapiini"), with the economically most important species placed in Coptodonini and Oreochromini.[2] Tilapia are mainly freshwater fish inhabiting shallow streams, ponds, rivers, and lakes, and less commonly found living in brackish water. Historically, they have been of major importance in artisanal fishing in Africa, and they are of increasing importance in aquaculture and aquaponics. Tilapia can become a problematic invasive species in new warm-water habitats such as Australia,[3] whether deliberately or accidentally introduced, but generally not in temperate climates due to their inability to survive in cold water.

Tilapia is the fourth-most consumed fish in the United States dating back to 2002. The popularity of tilapia came about due to its low price, easy preparation, and mild taste.[4]

History

.jpg.webp)

The aquaculture of Nile tilapia goes back to Ancient Egypt, where it was represented by the hieroglyph K1, of the Gardiner list: 𓆛

Tilapia was a symbol of rebirth in Egyptian art, and was in addition associated with Hathor. It was also said to accompany and protect the sun god on his daily journey across the sky. Tilapia painted on tomb walls, reminds us of spell 15 of the Book of the Dead by which the deceased hopes to take his place in the sun boat: "You see the tilapia in its [true] form at the turquoise pool", and "I behold the tilapia in its [true] nature guiding the speedy boat in its waters."[5]

Tilapia were one of the three main types of fish caught in Talmudic times from the Sea of Galilee, specifically the Galilean comb (Sarotherodon galilaeus). Today, in Modern Hebrew, the fish species is called amnoon (probably a compound of am "mother" and noon "fish"). In English, it is sometimes known by the name "St. Peter's fish", which comes from the story in the Gospel of Matthew about the apostle Peter catching a fish that carried a coin in its mouth, though the passage does not name the fish.[6] While the name also applies to Zeus faber, a marine fish not found in the area, a few tilapia species (Sarotherodon galilaeus, Oreochromis aureus, Coptodon zillii and Tristramella) are found in the Sea of Galilee, where the author of the Gospel of Matthew recounts the event took place. These species have been the target of small-scale artisanal fisheries in the area for thousands of years.[7][8]

The common name 'tilapia' is based on the name of the cichlid genus Tilapia, which is itself a latinization of thlapi, the Tswana word for "fish".[9] Scottish zoologist Andrew Smith named the genus in 1840.[10]

Characteristics

Tilapia typically have laterally compressed, deep bodies. Like other cichlids, their lower pharyngeal bones are fused into a single tooth-bearing structure. A complex set of muscles allows the upper and lower pharyngeal bones to be used as a second set of jaws for processing food (cf. morays), allowing a division of labor between the "true jaws" (mandibles) and the "pharyngeal jaws". This means they are efficient feeders that can capture and process a wide variety of food items.[11] Their mouths are protrusible, usually bordered with wide and often swollen lips. The jaws have conical teeth. Typically, tilapia have a long dorsal fin, and a lateral line which often breaks towards the end of the dorsal fin, and starts again two or three rows of scales below. Some Nile tilapia can grow as long as 2.0 ft.[12]

Other than their temperature sensitivity, tilapia exist in or can adapt to a very wide range of conditions. An extreme example is the Salton Sea, where tilapia introduced when the water was merely brackish now live in salt concentrations so high that other marine fish cannot survive.[13]

Tilapia are also known to be a mouth-brooding species, which means they carry the fertilized eggs and young fish in their mouths for several days after the yolk sac is absorbed.[12]

Gallery

_female_composite.jpg.webp) Giant kingfisher with tilapia

Giant kingfisher with tilapia

Lake Naivasha_with_fish.jpg.webp) African fish eagle with tilapia

African fish eagle with tilapia

Lake Naivasha

Species

Historically, all tilapia have been included in their namesake genus Tilapia.[2] In recent decades, some were moved into a few other genera, notably Oreochromis,[14] and Sarotherodon.[15] Even with this modification, it was apparent that Tilapia was strongly poly– or paraphyletic.[16] In 2013, a major taxonomic review resolved this by moving most former Tilapia to several other genera. As a consequence, none of the species that are of major economic importance remain in Tilapia, but are instead placed in Coptodon, Oreochormis and Sarotherodon.[2]

Exotic and invasive species

Tilapia have been used as biological controls for certain aquatic plant problems. They have a preference for a floating aquatic plant, duckweed (Lemna sp.) but also consume some filamentous algae.[17] In Kenya, tilapia were introduced to control mosquitoes, which were causing malaria, because they consume mosquito larvae, consequently reducing the numbers of adult female mosquitoes, the vector of the disease.[18] These benefits are, however, frequently outweighed by the negative aspects of tilapia as an invasive species.[19]

Tilapia are unable to survive in temperate climates because they require warm water. The pure strain of the blue tilapia, Oreochromis aureus, has the greatest cold tolerance and dies at 45 °F (7 °C), while all other species of tilapia die at a range of 52 to 62 °F (11 to 17 °C). As a result, they cannot invade temperate habitats and disrupt native ecologies in temperate zones; however, they have spread widely beyond their points of introduction in many fresh and brackish tropical and subtropical habitats, often disrupting native species significantly.[20] Because of this, tilapia are on the IUCN's 100 of the World's Worst Alien Invasive Species list.[21] In the United States, tilapia are found in much of the south, especially Florida and Texas, and as far north as Idaho, where they survive in power-plant discharge zones.[22] Tilapia are also currently stocked in the Phoenix, Arizona canal system as an algal growth-control measure. Many state fish and wildlife agencies in the United States, Australia, South Africa, and elsewhere consider them to be invasive species.[23]

Aquarium species

Larger tilapia species are generally poor community aquarium fish because they eat plants, dig up the bottom, and race with other fish. However, the larger species are often raised as a food source, because they grow rapidly and tolerate high stocking densities and poor water quality.

Smaller West African species, such as Coelotilapia joka and species from the crater lakes of Cameroon, are more popular. In specialised cichlid aquaria, tilapia can be mixed successfully with nonterritorial cichlids, armored catfish, tinfoil barbs, garpike, and other robust fish. Some species, including Heterotilapia buttikoferi, Coptodon rendalli, Pelmatolapia mariae, C. joka and the brackish-water Sarotherodon melanotheron, have attractive patterns and are quite decorative.[24]

| This article is part of a series on |

| Commercial fish |

|---|

| Large pelagic |

| Forage |

| Demersal |

| Mixed |

Commercial species

Tilapia were originally farmed in their native Africa and Levant. Fast-growing, tolerant of stocking density, and adaptable, tilapia have been introduced to and are farmed extensively in many parts of Asia and are increasingly common aquaculture targets elsewhere.

| Principal commercial tilapia species | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common name | Scientific name | Maximum length |

Common length |

Maximum weight |

Maximum age |

Trophic level |

Fish Base |

FAO | WoRMS | IUCN status |

| Nile tilapia | Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758) | 60 cm | cm | 4.324 kg | 9 years | 2.0 | [25] | [26][27] | [28] | Not assessed |

| Blue tilapia | - Oreochromis aureus (Steindachner, 1864) |

45.7 cm | 16 cm | 2.010 kg | years | 2.1 | [29] | [30] | Not assessed | |

| Nile tilapia + blue tilapia hybrid | cm | cm | kg | years | ||||||

| Mozambique tilapia | Oreochromis mossambicus (Peters, 1852) | 39 cm | 35 cm | 1.130 kg | 11 years | 2.0 | [31] | [32] | [33] | |

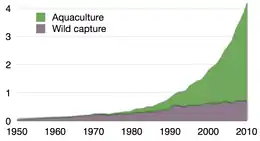

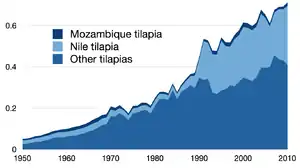

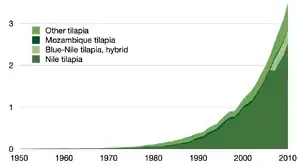

as reported by the FAO, 1950–2009 [35]

Aquaculture

Farmed tilapia production in 2002 worldwide was about 1.5 million tonnes (1.5 million long tons; 1.7 million short tons) annually, with an estimated value of US$1.8 billion,[36] about equal to those of salmon and trout.

Unlike carnivorous fish, tilapia can feed on algae or any plant-based food. This reduces the cost of tilapia farming, reduces fishing pressure on prey species, avoids concentrating toxins that accumulate at higher levels of the food chain, and makes tilapia the preferred "aquatic chickens" of the trade.[37]

Because of their large size, rapid growth, and palatability, tilapia cichlids are the focus of major farming efforts, specifically various species of Oreochromis, Sarotherodon, and Coptodon (all were formerly in the namesake genus Tilapia).[2] Like other large fish, they are a good source of protein and popular among artisanal and commercial fisheries. Most such fisheries were originally found in Africa, but outdoor fish farms in tropical countries, such as Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, and Indonesia, are underway in freshwater lakes.[38] In temperate zone localities, tilapiine farming operations require energy to warm the water to tropical temperatures. One method uses waste heat from factories and power stations.[39]

At 1.3 million tonnes per annum, China is the largest tilapia producer in the world, followed by Egypt with 0.5 million.[40] The US, by comparison, produces 10 thousand tonnes against a consumption of 2.5 million.[35]

In modern aquaculture, wild-type Nile tilapia are not too often seen, as the dark color of their flesh is not much desired by many customers, and because it has a bit of a reputation of being a rough fish associated with poverty.[41] However, they are fast-growing and give good fillets; leucistic ("red") breeds which have lighter meat have been developed and are very popular.

Hybrid stock is also used in aquaculture; Nile × blue tilapia hybrids are usually rather dark, but a light-colored hybrid breed known as "Rocky Mountain White" tilapia is often grown due to its very light flesh and tolerance of low temperatures.[41]

Commercially grown tilapia are almost exclusively male. This is typically done by adding male sex hormone in the food to the tilapia fry, causing any potential female tilapia to change sex to male.[27][42] It can also be achieved through hybridization of certain tilapia species or the use of so-called "supermales" that have homozygous male sex chromosomes (resulting in all their offspring receiving a male sex chromosome and thus becoming males).[42][43] Males are preferred because they grow much faster than females.[27] Additionally, because tilapia are prolific breeders, the presence of female tilapia results in rapidly increasing populations of small fish, rather than a stable population of harvest-size animals.[44]

Other methods of tilapia population control are polyculture, with predators farmed alongside tilapia or hybridization with other species.[45]

As food

Whole tilapia fish can be processed[46] into skinless, boneless (pin-bone out) fillets: the yield is from 30 to 37%, depending on fillet size and final trim.[47][48] In some of the commercial strains, the yield has been reported up to 47% at harvest weight.[49][50]

Tilapia is one of several commercially important aquaculture species (including trout, barramundi and channel catfish) susceptible to off-flavors. These 'muddy' or 'musty' flavors are normally caused by geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol, organic products of ubiquitous cyanobacteria that are often present or bloom sporadically in water bodies and soil.[51] These flavors are no indication of freshness or safety of the fish, but they make the product unattractive to consumers. Simple quality control procedures are known to be effective in ensuring the quality of fish entering the market.

Tilapia have very low levels of mercury,[52] as they are fast-growing, lean, and short-lived, with a primarily vegetarian diet, so do not accumulate mercury found in prey.[53] Tilapia are low in saturated fat, calories, carbohydrates, and sodium, and are a good protein source. They also contain the micronutrients phosphorus, niacin, selenium, vitamin B12, and potassium.[54]

Some research has found that tilapia may be a less nutritious fish than generally believed. The Wake Forest University School of Medicine released a report in 2008 showing that the fish's omega-3 fatty acid content is often far lower than that of other commonly eaten fish species. The same study also showed that their omega-6 fatty acid levels were unusually high. Multiple studies have evaluated the effects of adding flaxseed derivatives (a vegetable source of omega-3 fatty acids) to the feed of farmed tilapia. These studies have found both the more common omega-3 fatty acid found in the flax, ALA and the two types almost unique to animal sources (DHA and EPA), increased in the fish fed this diet.[55][56] Guided by these findings, tilapia farming techniques could be adjusted to address the nutritional criticisms directed at the fish while retaining its advantage as an omnivore capable of feeding on economically and environmentally inexpensive vegetable protein. Adequate diets for salmon and other carnivorous fish can alternatively be formulated from protein sources such as soybean, although soy-based diets may also change in the balance between omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids.[57]

Miscellaneous uses

Tilapia serve as a natural, biological control for most aquatic plant problems. Tilapia consume floating aquatic plants, such as duckweed watermeal (Lemna sp.), most "undesirable" submerged plants, and most forms of algae.[58] In the United States and countries such as Thailand, they are becoming the plant-control method of choice, reducing or eliminating the use of toxic chemicals and heavy metal-based algaecides.

Tilapia rarely compete with other "pond" fish for food. Instead, because they consume plants and nutrients unused by other fish species and substantially reduce oxygen-depleting detritus, adding tilapia often increases the population, size, and health of other fish. They are used for zoo ponds as a source of food for birds.

Tilapia can be farmed together with shrimp in a symbiotic manner, positively enhancing the productive output of both.

Arkansas stocks many public ponds and lakes to help with vegetation control, favoring tilapia as a robust forage species and for anglers.

In Kenya, tilapia help control mosquitoes which carry malaria parasites. They consume mosquito larvae, which reduces the numbers of adult females, the disease's vector.[18]

In Brazil, nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fish skin applied as a bandage is being used in a new clinical trial to treat burn injuries.[59] In the United States, tilapia skin has been used to successfully treat third-degree wounds to the paws of two black bears caught in California's Thomas wildfire,[60][61] and also to treat burns on the paws of a black bear from California's Carr wildfire.[62] Nile tilapia skin has completed a phase III clinical trial for burn treatment, but no results have been posted as of November 2020.[63]

Parasites

As with most fish, tilapia harbor a variety of parasites. For the monogeneans, these especially include species of the megadiverse genus Cichlidogyrus, which are gill parasites. Species of Enterogyrus are parasites in the digestive system. Tilapia, as important aquaculture fishes, have been introduced widely all over the world, and often carried their monogenean parasites with them. In South China, a 2019 study has shown that nine species of monogeneans were carried by introduced tilapia.[64]

See also

References

- Fisheries and Aquaculture Department Statistics UN Food and Agriculture Department

- Andreas R.Dunz & Ulrich K.Schliewen (2013). "Molecular phylogeny and revised classification of the haplotilapiine cichlid fishes formerly referred to as Tilapia". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 68 (1): 64–80. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2013.03.015. PMID 23542002.

- "Tilapia". Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry.

- "Tilapia | Seafood Health Facts". www.seafoodhealthfacts.org. Retrieved 2017-02-01.

- Gay Robin: Women in ancient Egypt (p. 188), British museum press, 1993, ISBN 0-7141-0956-8

- Matthew 17:24–27

- Baker, Jenny (1988). Simply Fish. London: Faber & Faber. p. 197. ISBN 0-571-14966-9.

- Rosencrans, Joyce (2003-07-16). "Tilapia is a farmed fish of biblical fame". The Cincinnati Post. E. W. Scripps Company. Archived from the original on 2006-02-18. Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- Chapman, Frank A. (July 1992). "Culture of Hybrid Tilapia: A Reference Profile". Circular 1051. University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- "Genera Summary: Tilapia". Catalog of Fish – W. N. Eschmeyer; California Academy of Sciences. FishBase. June 2007. Archived from the original on 2000-10-27. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- Loiselle, P.V. (1994). The Cichlid Aquarium. Tetra Press. ISBN 1-56465-146-0.

- "What Is the Origin of Tilapia Fish?". Retrieved 2017-02-01.

- Science and the CSU

The Salton Sea: Fishing for Answers

A half-century later, a few species of fish have been hearty enough to survive. One of them is the tilapia and its key to the survival of the Salton’s ecosystem, which includes millions of birds that depend on them for food...

“The salinity level of the Salton Sea is about 45 parts per thousand (ppt), which is about 30% saltier than the ocean" - "Oreochromis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. 16 August 2007.

- "Sarotherodon". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. 16 August 2007.

- Nagl, Sandra; Herbet Tichy; Werner E. Mayer; Irene E. Samonte; Brendan J. McAndrew; Jan Klein (2001). "Classification and Phylogenetic Relationships of African Tilapiine Fishes Inferred from Mitochondrial DNA Sequences". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 20 (3): 361–374. doi:10.1006/mpev.2001.0979. PMID 11527464.

- John W. Cross (2013-08-13). "Aquatic Weed Control". Mobot.org. Retrieved 2013-09-14.

- Petr, T (2000). "Interactions between fish and aquatic macrophytes in inland waters. A review". FAO Fisheries Technical Papers. 396.

- "Oreochromis aureus". Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- "Global Invasive Species Programme, Invasive Species Information, Tilapia". Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- "100 of the World's Worst Alien Invasive Species". Invasive Species Specialist Group. IUCN Species Survival Commission. Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- "NAS – Nonindigenous Aquatic Species". USGS. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- "Oreochromis mossambicus (fish)". Global Invasive Species Database. IUCN Species Survival Commission. Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- "Keeping Tilapia in Aquariums". Tilapia. AC Tropical Fish. 2008. Retrieved 2009-01-19.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Oreochromis niloticus" in FishBase. September 2012 version.

- "Oreochromis niloticus Linnaeus, 1758)". Species Fact Sheet. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- Nico, L.G.; P.J. Schofield; M.E. Neilson (2019). "Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758)". Food and Agriculture Organization, United Nations. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "Oreochromis niloticus". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Oreochromis aureus" in FishBase. September 2012 version.

- "Oreochromis aureus". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Oreochromis mossambicus" in FishBase. September 2012 version.

- "Oreochromis mossambicus (Peters, 1852)". Species Fact Sheet. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- "Oreochromis mossambicus (Peters, 1852)". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- Herdson D, Priede I (2011). "Oreochromis mossambicus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- Based on data sourced from the FishStat database

- De Silva, S.S; Subasinghe, R.P.; Bartley, D.M.; Lowther, A. (2004). "Tilapias as Alien Aquatics in Asia and the Pacific: A Review". FAO Fisheries Technical Paper – No. 453. Archived from the original on 17 February 2008.

- Barlow, G. W. (2000). The Cichlid Fishes. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing. ISBN 0-7382-0376-9.

- "Title unknown". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Archived from the original on May 17, 2006.

- "GO FISH, Egyptian Style". Ag Innovation News. Agricultural Utilization Research Institute.

- "Finding more fish, between Egypt and Vietnam". eco-business.com. 28 October 2010. Archived from the original on 12 November 2010. Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- "Tilapia Aquaculture". Miami Aqua-culture, Inc. Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- Wan, Z.Y.; G. Lin; G. Yue (2019). "Genes for sexual body size dimorphism in hybrid tilapia (Oreochromis sp. x Oreochromis mossambicus)". Aquaculture and Fisheries. 4 (6): 231–238. doi:10.1016/j.aaf.2019.05.003.

- Baroiller, J.F.; H. D'Cotta; E. Bezault; S. Wessels; G. Hoerstgen-Schwark (2009). "Tilapia sex determination: Where temperature and genetics meet". Comp Biochem Physiol a Mol Integr Physiol. 153 (1): 30–38. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.11.018. PMID 19101647.

- "Fact about Tilapia Fish (Oreochromis spp.)". Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- Prein, M. H. (1993). "Multivariate Methods in Aquaculture Research: Case Studies of Tilapia in Experimental and Commercial Systems". Manilla: ICLARM. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Whole Fish to Fillet (HACCP procedures videos of Tilapia fillet processing)". Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- "Different Processing Styles of Tilapia Fillets". Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- "Title unknown". Tropical Aquaculture Products, Inc. Archived from the original on 2010-02-13. Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- Ødegård, Jørgen; Alvarez, Alejandro Tola; Vera, Mayet de; Skaarud, Anders; Joshi, Rajesh (2019-08-05). "Genomic prediction for commercial traits using univariate and multivariate approaches in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus)". bioRxiv: 725143. doi:10.1101/725143.

- Gjøen, H. M.; T. H. E. Meuwissen; Woolliams, J. A.; Joshi, R. (May 2018). "Maternal, dominance and additive genetic effects in Nile tilapia; influence on growth, fillet yield and body size traits". Heredity. 120 (5): 452–462. doi:10.1038/s41437-017-0046-x. ISSN 1365-2540. PMC 5889400. PMID 29335620.

- Robin, Joël; Cravedi, Jean-Pierre; Hillenweck, Anne; Deshayes, Cyrille; Vallod, Dominique (2006). "Off flavor characterization and origin in French trout farming". Aquaculture. 260 (1–4): 128–138. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.05.058.

- Mercury Levels in Commercial Fish and Shellfish (1990–2010) fda.gov

- "Nutritional Facts". Tropical Aquaculture Products, Inc. Archived from the original on 2012-04-27. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- "Nutrition Facts and Analysis for Fish, tilapia, cooked, dry heat". Retrieved 2014-01-26.

- Shapira, N; et al. (March 2009). "n-3 PUFA fortification of high n-6 PUFA farmed tilapia with linseed could significantly increase dietary contribution and support nutritional expectations of fish". J. Agric. Food Chem. 57 (6): 2249–2254. doi:10.1021/jf8029258. PMID 19243170.(subscription required)

- Aguiar, AC; et al. (September 2007). "Effect of flaxseed oil in diet on fatty acid composition in the liver of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus)". Arch Latinoam Nutr. 57 (3): 273–277. PMID 18271406.

- Espe, Marit; et al. (May 2006). "Can Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) grow on diets devoid of fish meal?". Aquaculture. 255 (1–4): 255–262. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2005.12.030.(subscription required)

- Cross, John W. "Aquatic Weed Control". The Charms of Duckweed. Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- "Why this Brazilian city uses tilapia fish skin to treat burn victims". PBS. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- "Two bears were badly burned in wildfires, and fish skin helped heal them". Washington Post. Retrieved 2018-02-05.

- "Bears Burned in California Wildfires Healed With Fish Skins, Released to Wild". UC Davis. Retrieved 2018-08-10.

- "WILDFIRES: Bear Treated With Fish Skins; Firefighters Return". UC Davis. Retrieved 2018-08-10.

- https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04202289?term=Oreochromis+Niloticus&draw=2&rank=1

- Zhang, Shuai; Zhi, Tingting; Xu, Xiangli; Zheng, Yingying; Bilong Bilong, Charles Félix; Pariselle, Antoine; Yang, Tingbao (2019). "Monogenean fauna of alien tilapias (Cichlidae) in south China". Parasite. 26: 4. doi:10.1051/parasite/2019003. ISSN 1776-1042. PMC 6361074. PMID 30714897.

Further reading

- Logan, Cheryl A.; Alter, S. Elizabeth; Haupt, Alison J.; Tomalty, Katharine; Palumbi, Stephen R. (2008). "An impediment to consumer choice: Overfished species are sold as Pacific red snapper". Biological Conservation. 141 (6): 1591–1599. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2008.04.007. ISSN 0006-3207.

- FAO Fishery Information, Data & Statistics Service (1993). "Aquaculture production (1985-1991)". FAO Fisheries Circular. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 815: 20–21.

- Trewavas, Ethelwynn (1983). Tilapiine fish of the genera Sarotherodon, Oreochromis and Danakilia. London: British Museum (Natural History). ISBN 0-565-00878-1.

- McCrary, Jeffrey K; Castro, Mark; McKaye, Kenneth R. (2005). "Mercury in Fish From Two Nicaraguan Lakes: A Recommendation for Increased Monitoring of Fish for International Commerce" (PDF). Environmental Pollution. pp. 513–518. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-03.

.png.webp)