Babe Ruth's called shot

Babe Ruth's called shot was a much-debated moment in baseball history, the home run hit by Babe Ruth of the New York Yankees in the fifth inning of Game 3 of the 1932 World Series, held on October 1, 1932, at Wrigley Field in Chicago. During the at-bat, Ruth made a pointing gesture which existing film confirms, but whether he was promising a home run, or gesturing at fans or the other team, remains in dispute.

There is no dispute over the general events of the moment. All the reports say that the Chicago Cubs' "bench jockeys" were riding Ruth mercilessly and that Ruth, rather than ignoring them was "playing" with them through words and gestures.

The longtime debate is over the nature of one of Ruth's gestures. It is unclear if he pointed to the center field, to the pitcher (Charlie Root) or to the Cubs bench. Even the films of the at-bat (by amateur filmmaker Matt Miller Kandle, Sr.) that emerged during the 1990s have not provided anything conclusive.

With the score tied 4-4 in the fifth inning of game three, he took strike one from Root. As the Cubs players heckled Ruth and the fans hurled insults, Ruth held up his hand pointing at either Root, the Cubs dugout or center field. He then repeated this gesture after taking strike two.

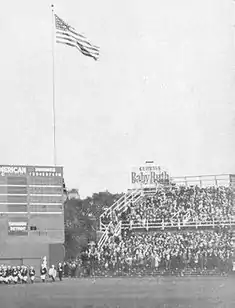

Root's next pitch was a curveball that Ruth hit at least 440 feet to the deepest part of the center-field near the flag pole (some estimates are as much as 490 feet). The ground distance to the center-field corner, somewhat right of straightaway center was 440 feet. The ball landed a little bit to the right of the 440 corners and farther back, apparently in the temporary seating in Sheffield Avenue behind the permanent interior bleacher seats. Calling the game over the radio, broadcaster Tom Manning shouted, "The ball is going, going, going, high into the center-field stands...and it is a home run!" Ruth himself later described the hit as "past the flagpole" which stood behind the scoreboard and the 440 corners. Ruth's powerful hit was aided by a strong carrying wind that day.[1]

Newsreel footage (available in MLB's 100 Years of the World Series) shows that Ruth was crowding the plate and nearly stepped forward out of the batter's box, inches away from the risk of being called out (Rule 6.06a). The film also shows that as he rounded first base, Ruth looked toward the Cubs dugout and made a waving-off gesture with his left hand; then as he approached third, he made another mocking gesture, a two-armed "push" motion, toward the suddenly quiet Cubs bench. Many reports[2] have claimed that Ruth "thumbed his nose" at the Cubs dugout, but the existing newsreel footage does not show that. (If it occurred, it might have been considered vulgar and could have been edited out.) Attending the game was Franklin Delano Roosevelt,[3] soon-to-be-elected 32nd President of the United States, as well as John Paul Stevens, future Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court.[4] FDR reportedly had a laugh as he watched Ruth round the bases.[5] When he crossed home plate, Ruth could no longer hide his smile, and he was patted by his exuberant teammates when he reached the Yankees dugout.[6]

Root was left in the game, but for only one pitch, which Lou Gehrig drilled into the right-field seats for his second home run of the day. The Yankees won the game 7–5 and the next day they finished off the demoralized Cubs 13–6, completing a four game sweep of the World Series.

Origins of the called-shot story

Ruth's second home run in game 3 probably would have been merely an exclamation point for the 1932 World Series and for Ruth's career, had it not been for reporter Joe Williams. Williams was a respected but opinionated sports editor for the Scripps-Howard newspapers. In a late edition the same day of the game, Williams wrote this headline that appeared in the New York World-Telegram, evoking billiards terminology: "RUTH CALLS SHOT AS HE PUTS HOME RUN NO. 2 IN SIDE POCKET." [7] Williams' summary of the story included, "In the fifth, with the Cubs riding him unmercifully from the bench, Ruth pointed to center and punched a screaming liner to a spot where no ball had been hit before." Apparently Williams' article was the only one written the day of the game that made a reference to Ruth pointing to center field. The wide circulation of the Scripps-Howard newspapers probably gave the story life, as many read Williams' article and assumed it was accurate. A couple of days later, other stories started to appear stating that Ruth had called his shot, a few even written by reporters who were not at the game.

The story would have had some initial credibility, given Ruth's many larger-than-life achievements, including past reported incidents of promising sick child Johnny Sylvester that he would "hit a home run for him" and then fulfilling that promise soon after. In the public mind, Ruth "calling his shot" had precedent.

At the time, Ruth did not clarify the matter, initially stating that he was merely pointing towards the Cubs dugout to tell them he still had one more strike. At one point very early on, he said, "It's in the papers, isn't it?" In another interview, this one with respected Chicago sports reporter John Carmichael, Ruth said he did not point to any particular spot, but that he just wanted to give the ball a good ride. Soon, however, the media-savvy Ruth was going along with the story that he had called his shot, and his subsequent versions over the years became more dramatic. "In the years to come, Ruth publicly claimed that he did, indeed, point to where he planned to send the pitch."[8] One newsreel footage, Ruth voiced over the called shot scene with the remarks, "Well, I looked out at center field and I pointed. I said, 'I'm gonna hit the next pitched ball right past the flagpole!' Well, the good Lord must have been with me." In his 1948 autobiography, Ruth gave another enhanced version by stating he told his wife "I'll belt one where it hurts them the most" and that the idea of calling his own shot then came to him.[9] Ruth then recounts the at-bat:

No member of either team was sorer than I was. I had seen nothing my first time at bat that came close to looking good to me, and that only made me more determined to do something about taking the wind out of the sails of the Chicago players and their fans. I mean the fans who had spit on Claire [i.e., Ruth's wife].

I came up in the fourth inning [sic] with Earle Combs on base ahead of me. My ears had been blistered so much before in my baseball career that I thought they had lost all feeling. But the blast that was turned on me by Cub players and some of the fans penetrated and cut deep. Some of the fans started throwing vegetables and fruit at me.

I stepped back out of the box, then stepped in. And while Root was getting ready to throw his first pitch, I pointed to the bleachers which rise out of deep center field. Root threw one right across the gut of the plate and I let it go. But before the umpire could call it a strike - which it was - I raised my right hand, stuck out one finger and yelled, "Strike one!"

The razzing was stepped up a notch.

Root got set and threw again - another hard one through the middle. And once again I stepped back and held up my right hand and bawled, "Strike two!" It was.

You should have heard those fans then. As for the Cub players they came out on the steps of their dugout and really let me have it.

I guess the smart thing for Charlie to have done on his third pitch would have been to waste one.

But he didn't, and for that I've sometimes thanked God.

While he was making up his mind to pitch to me I stepped back again and pointed my finger at those bleachers, which only caused the mob to howl that much more at me.

Root threw me a fast ball. If I had let it go, it would have been called a strike. But this was it. I swung from the ground with everything I had and as I hit the ball every muscle in my system, every sense I had, told me that I had never hit a better one, that as long as I lived nothing would ever feel as good as this.

I didn't have to look. But I did. That ball just went on and on and on and hit far up in the center-field bleachers in exactly the spot I had pointed to.

To me, it was the funniest, proudest moment I had ever had in baseball. I jogged down toward first base, rounded it, looked back at the Cub bench and suddenly got convulsed with laughter.

You should have seen those Cubs. As Combs said later, "There they were-all out on the top step and yelling their brains out - and then you connected and they watched it and then fell back as if they were being machine-gunned."

That home run-the most famous one I ever hit - did us some good. It was worth two runs, and we won that ball game, 7 to 5.[10]

Ruth explained he was upset about the Cubs' insults during the series, and was especially upset when someone spat on his wife Claire, and he was determined to fix things.[11] Ruth not only said he deliberately pointed to center with two strikes, he said he pointed to center even before Root's first pitch.[12]

Others helped perpetuate the story over the years. Tom Meany, who worked for Joe Williams at the time of the called shot, later wrote a popular but often embellished 1947 biography of Ruth. In the book, Meany wrote, "He pointed to center field. Some say it was merely as a gesture towards Root, others that he was just letting the Cubs bench know that he still had one big one left. Ruth himself has changed his version a couple of times... Whatever the intent of the gesture, the result was, as they say in Hollywood, slightly colossal."[13]

Despite the fact that the article he wrote on the day of the game appears to have been the source of the entire legend, over the ensuing years, Joe Williams himself came to doubt the veracity of Ruth calling his shot.

Another part of folklore has Ruth being mad at the Cubs in general for the perceived slight of cutting Babe's ex-Yankee teammate, Mark Koenig, now with the Cubs, out of his full World Series share.

Nonetheless, the called shot further became etched as truth into the minds of thousands of people after the 1948 film The Babe Ruth Story, which starred William Bendix as Ruth. The film took its material from Ruth's autobiography, and hence did not question the veracity of the called shot. Two separate biographical films made in the 1990s also repeated this gesture in an unambiguous way, coupled with Ruth hitting the ball over the famous ivy-covered wall, which did not actually exist at Wrigley Field until five years later.

Eyewitness accounts

Eyewitness accounts were equally inconclusive and widely varied, with some of the opinions possibly skewed by partisanship.

- "Don't let anybody tell you differently. Babe definitely pointed." — Cubs public-address announcer Pat Pieper (As public-address announcer Pieper sat next to the wall separating the field from the stands, between home plate and third base. In 1966 he spoke with the Chicago Tribune "In the Wake of the News" sports columnist David Condon: "Pat remembers sitting on the third base side and hearing [Cubs' pitcher] Guy Bush chide Ruth, who had taken two strikes. According to Pat, Ruth told Bush: 'That's strike two, all right. But watch this.' 'Then Ruth pointed to center field, and hit his homer,' Pat continues. 'You bet your life Babe Ruth called it.'")[14]

- "My dad took me to see the World Series, and we were sitting behind third base, not too far back.... Ruth did point to the center-field scoreboard. And he did hit the ball out of the park after he pointed with his bat. So it really happened." former Associate Justice John Paul Stevens, United States Supreme Court[15]

- "What do you think of the nerve of that big monkey. Imagine the guy calling his shot and getting away with it." – Lou Gehrig[16]

- The Commissioner of Baseball, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, attended the game with his young nephew, and both had a clear view of the action at home plate. Landis himself never commented on whether he believed Ruth called the shot, but his nephew believes that Ruth did not call it.

- Shirley Povich, The Washington Post columnist detailed in an interview with Hall of Fame catcher Bill Dickey. "Ruth was just mad about that quick pitch, Dickey explained. He was pointing at Root, not at the centerfield stands. He called him a couple of names and said, "Don't do that to me anymore, you blankety-blank."[17]

- Ray Kelly, Ruth's guest for the game, said "He absolutely did it ... I was right there. Never in doubt."[18]

- Erle V. Painter, the Yankees athletic trainer at the time, shared his recollection of the shot with the Baseball Hall of Fame. He stated, "Ruth made a three-quarter turn to the stands and held up one finger. It was plain he was signifying one strike didn't mean he was out. Root put over another strike and the Babe repeated the pantomime, holding up two fingers this time. Then, before taking his stance, he swept his left arm full length and pointed to the centerfield fence."[19]

The called shot particularly irked Root. He had a fine career, winning over 200 games, but he would be forever remembered as the pitcher who gave up the "called shot", much to his annoyance.[20] When he was asked to play himself in the 1948 film about Ruth, Root turned it down when he learned that Ruth's pointing to center field would be in the film. Said Root, "Ruth did not point at the fence before he swung. If he had made a gesture like that, well, anybody who knows me knows that Ruth would have ended up on his ass. The legend didn't get started until later." Root's teammate, catcher Gabby Hartnett, also denied that Ruth called the shot. On the other hand, according to baseball historian and author Michael Bryson, it is noted that at that point in the game, Ruth pointed toward the outfield to draw attention to a loose board that was swinging free. Some people may have misinterpreted this as a "called shot", but Cubs personnel knew exactly what he was pointing to, and hammered the board back into place.[21]

In 1942, during the making of The Pride of the Yankees, Babe Herman (who was at that time a teammate of Root with the minor league Hollywood Stars) was on the movie set as a double for both Ruth (who played himself in most scenes) and Gary Cooper (who played Lou Gehrig). Herman re-introduced Root and Ruth on set and the following exchange (later recounted by Herman to baseball historian Donald Honig) took place:

- Root: "You never pointed out to center field before you hit that ball off me, did you?"

- Ruth: "I know I didn't, but it made a hell of a story, didn't it?"

Root went to his grave vehemently denying that Ruth ever pointed to center field.

Rediscovered 16 mm films

In the 1970s, a 16 mm home movie of the called shot surfaced and some believed it might put an end to the decades-old controversy. The film was shot by an amateur filmmaker named Matt Miller Kandle, Sr. Only family and friends had seen the film until the late 1980s. Two frames from the film were published in the 1988 book, Babe Ruth: A Life in Pictures, by Lawrence S. Ritter and Mark Rucker, on p. 206. The film was broadcast on a February 1994 FOX television program called Front Page.[22] Later in 1994, still images from the film appeared in filmmaker Ken Burns documentary film Baseball.

The film was taken from the grandstands behind home plate, off to the third base side. One can clearly see Ruth's gesture, although it is hard to determine the angle of his pointing. Some contend Ruth's extended arm is pointing more to the left field direction, toward the Cubs bench, which would be consistent with his (continued) gesturing toward the bench while rounding the bases after the hit. Others who have studied the film closely assert that in addition to the broader gestures, Ruth did make a quick finger point in the direction of Cubs pitcher Charlie Root, or center field just as Root was winding up.

In 1999, another 16 mm film of the called shot appeared. This one had been shot by inventor Harold Warp, and coincidentally it was the only major league baseball game Warp ever attended. The rights to his footage were sold to ESPN which aired it as part of the network's SportsCentury program in 2000 as well as a countdown show of Best Damn Sports Show. Warp's film has not been as widely seen by the public as Kandle's film, but those who have seen it and have offered a public opinion on the matter seem to feel that it shows Ruth did not call his shot. The film itself shows the action much more clearly than the Kandle film, showing Ruth visibly shouting something either at Root or at the Cub dugout while pointing.

The authors of the book Yankees Century also believe the Warp film proves conclusively that the home run was not at all a "called shot". However, Montville's 2006 book, The Big Bam, asserts that neither film answers the question definitively.

Legacy and cultural references

Shortly after the called shot, the Chicago-based Curtiss Candy Company, makers of the Baby Ruth candy bar, installed a large advertising sign on the rooftop on one of the apartment buildings on Sheffield Avenue. The sign, which read "Baby Ruth", was just across the street from where Ruth's home run had landed. Until the 1970s, when the aging sign was taken down, Cubs fans at Wrigley Field had to endure this not-so-subtle reminder of the "called shot".

In the 1948 biographical film The Babe Ruth Story, Ruth delivers on a promise he made to a young cancer patient that he would hit a home run. Not only does Ruth succeed in fulfilling the promise, but the child is subsequently cured of his cancer.

In an early scene in the 1984 film, The Natural, a Ruth-like player called "the Whammer" points his bat menacingly toward and past Roy Hobbs, declaring his own "called shot." However, Hobbs strikes the Whammer out on three pitches.

Major league slugger Jim Thome used a similar bat-pointing gesture as part of his normal preparation for an at-bat.

In the 1989 film Major League, the climax of the movie depicts Indians catcher Jake Taylor pointing towards the outfield, clearly making a reference to Ruth's called shot. Fittingly, Jake was playing against the New York Yankees. The pitcher then throws a pitch high and inside, referencing Root's suggestion that he would have thrown at Ruth if he had really called his shot. Jake repeats the called shot, but instead of going for a home run, bunts the next pitch for a modified squeeze play, allowing the winning run to come in from second base.

In the 1992 The Simpsons episode "Homer at the Bat", Homer Simpson, when up for bat at a softball game, points to the stands. When he hits the ball and it goes to the opposite side, he points to that side and pretends that's where he meant to hit it. In the 1999 episode "Wild Barts Can't Be Broken", Ruth's "illegitimate great-grandson" Babe Ruth IV is a hitter for the Springfield Isotopes. While at bat, he points towards the right field bleachers at Duff Stadium, looking at a "dying little boy" (shown to be Bart, who was healthy), then points down to signal a bunt. He is immediately tagged out, as three opposing players were a mere few feet away from him.

In the 1993 film, The Sandlot, the characters are fans of Ruth and reference his called shot by imitating it.

In 2000, a novel titled Babe & Me was published by author Dan Gutman. A young boy travels back in time to prove the shot was called.

In George Carlin's 2001 book Napalm and Silly Putty, he "reveals" that, "Contrary to popular belief, Babe Ruth did not call his famous home run shot. He was actually giving the finger to a hot dog vendor who had cheated him out of twelve cents."

In the mid-2000s Bud Light made a commercial of the called shot, humorously depicting Ruth pointing towards center field because he had spotted a vendor selling Bud Light there.

In 2005, the jersey which Ruth was wearing during the game was sold for US$1,056,630 at auction.[23]

In the 2006 computer animated film Everyone's Hero, the shot is instead played by protagonist Yankee Irving using Ruth's famed bat. Yankee hits a home run on Ruth's suggestion. According to the film, the story takes place during the 1932 World Series.

In the 2006 movie The Benchwarmers, one of the main characters, Richie, points his hand towards center field, resembling Ruth's called shot. Richie's hand then starts dragging down to a spot right in front of home plate. Richie then hits the ball right where his hand points to.

In the 2007 video game Team Fortress 2, the baseball fanatic Scout, in one of his taunts called the Home Run, points at the sky in the distance and then whacks an opponent with his baseball bat, hitting the player in the direction he pointed, landing an instant kill on anyone caught by it.

At WrestleMania 35, a vignette of the famous home run was played before John Cena reprised his 'Doctor of Thuganomics' gimmick, interrupting Elias.

References

- Montville, Leigh (2006). The Big Bam: the life and times of Babe Ruth. Doubleday. p. 502. ISBN 0-385-51437-9.

- "Is This The Ball?". Baberuthbaseball.com. 1932-10-01. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=j68wAAAAIBAJ&sjid=pIoDAAAAIBAJ&pg=6123,1564844&dq=world+series&hl=en

- Toobin, Jeffrey (March 22, 2010). "After Stevens". The New Yorker. p. 41.

- "Sports Moment | American History Lives at American Heritage". Americanheritage.com. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0FCI/is_10_62/ai_107488942/

- KARL VOGEL Lincoln Journal, Star. "Minden family's film shows Babe Ruth's "called shot' homer." Lincoln Journal Star (NE) 24 Dec. 1999: NewsBank - Archives. Web. 23 Feb. 2016.

- Chris Harry, Sentinel Staff Writer. "ON HIS HONOR; Justice John Paul Stevens witnessed Babe Ruth's historic 'called' shot." Orlando Sentinel, The (FL) 30 Sept. 2007: NewsBank. Web. 17 Feb. 2016.

- Ruth, Babe; Considine, Bob (1948). The Babe Ruth Story: As Told to Bob Considine. E.P. Dutton. p. 191.

- Ruth, Babe; Considine, Bob (1948). The Babe Ruth Story: As Told to Bob Considine. E.P. Dutton. pp. 193–194.

- "Daily News America – Breaking national news, video, and photos – Homepage – NY Daily News". Articles.nydailynews.com. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- "Ruth's Called Shot Among Greatest World Series Homers – 500 Home Run Club – The Most Inspiring Sluggers in Baseball History". 500hrc.com. 2006-09-30. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- Meany, Tom (1947). Babe Ruth: The Rollicking Life Story of Baseball's Big Fellow. A.S. Barnes.

- Condon, David (February 17, 1966). "In the Wake of the News". Chicago Tribune. p. 11.

- "After Stevens". The New Yorker. March 22, 2010. p. 41.

- "Lou Gehrig Quotes". Baseball-Almanac.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-25.

- Povich, Shirley (1969). All These Mornings.

- "Ray Kelly, 83, Babe Ruth's Little Pal, Dies". The New York Times. November 14, 2001. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

- Atkin, Ross (10 April 1980). "BASEBALL Ruth lore: fact or fiction?". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- Snell, Roger. Root for the Cubs. Archived from the original on 2009-06-18. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- The Twenty-Four Inch Home Run

- Front Page TV Show https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E99eUE9b4GY [unavailable on request of the Kandle family]

- "eMuseum of Great Uniforms & Memorabilia". Grey Flannel Auctions Blog. 6 February 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

Bibliography

- Creamer, Robert W. (1974). Babe: The Legend Comes to Life. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-21770-4.

- Honig, Donald (1985). Baseball America: The Heroes of the Game and the Times of Their Glory. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-025-53580-3.

- Sherman, Ed (2014). Babe Ruth's Called Shot: The Myth and Mystery of Baseball's Greatest Home Run. Guilford, CT: Lyons Press. ISBN 978-0-762-78539-1.

- Snell, Roger (2009). Root for the Cubs: Charlie Root & the 1929 Chicago Cubs. Nicholasville, KY: Wind Publications. ISBN 978-1-893-23995-1.

- Stout, Glenn (2002). Yankees Century: 100 Years of New York Yankees Baseball. New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-08527-0.