Major League Baseball Game of the Week

The Major League Baseball Game of the Week (GOTW) is the de facto title for nationally televised coverage of regular season Major League Baseball games. The Game of the Week has traditionally aired on Saturday afternoons. When the national networks began televising national games of the week, it opened the door for a national audience to see particular clubs. While most teams were broadcast, emphasis was always on the league leaders and the major market franchises that could draw the largest audience.

History

1950s

In 1953, ABC-TV executive Edgar J. Scherick (who would later go on to create Wide World of Sports) broached a Saturday Game of the Week-TV sport's first network series. At the time, ABC was labeled a "nothing network" that had fewer outlets than CBS or NBC. ABC also needed paid programming or "anything for bills" as Scherick put it. At first, ABC hesitated at the idea of a nationally televised regular season baseball program.

In April 1953, Edgar Scherick set out to sell teams broadcasting rights, but only got the Philadelphia Athletics, Cleveland Indians, and Chicago White Sox to sign on. To make matters worse, Major League Baseball blacked out the Game of the Week on any TV stations within 50 miles of a ballpark. Major League Baseball, according to Scherick, insisted on protecting local coverage and didn't care about national appeal. ABC though, did care about the national appeal and claimed that "most of America was still up for grabs."

In 1953, ABC earned an 11.4 rating for their Game of the Week telecasts. Blacked-out cities had 32% of households. In the rest of the United States, 3 in 4 TV sets in use watched Dizzy Dean and Buddy Blattner call the games for ABC.

In 1955, CBS took over the Game package, adding Sunday telecasts in 1957. NBC began its own Saturday and Sunday coverage in 1957 and 1959, respectively. In 1960, ABC resumed Saturday telecasts; that year the "Big 3" networks aired a combined 123 games. As ABC's Edgar Scherick later observed, "In '53, no one wanted us. Now teams begged for Game's cash." That year, the NFL began a US$14.1 million revenue-sharing pact. Dean and Blattner continued to call the games for CBS, with Pee Wee Reese replacing Blattner in 1960. Gene Kirby, who'd worked with Dean and Blattner for ABC and Mutual radio, also contributed to the CBS telecasts as a producer and announcer.

1960s

By 1965, Major League Baseball ended Game of the Week blackouts in cities with MLB clubs. Other cities within fifty miles of an MLB stadium got $6.5 million for exclusivity, and split the pot.

On March 17, 1965, Jackie Robinson became the first black network broadcaster for Major League Baseball. According to ABC Sports producer Chuck Howard, despite Robinson having a high, stabbing voice, great presence, and sharp mind, all he lacked was time.

In 1965, ABC[1] provided the first-ever nationwide baseball coverage with weekly Saturday broadcasts on a regional basis. ABC paid $5.7 million for the rights to the 28 Saturday/holiday Games of the Week. ABC's deal covered all of the teams except the New York Yankees and Philadelphia Phillies (who had their own television deals) and called for three regionalized games on Saturdays, Independence Day, and Labor Day. ABC blacked out the games in the home cities of the clubs playing those games. Chris Schenkel, Keith Jackson, and Merle Harmon were the principal play-by-play announcers for ABC's coverage.

NBC's Game of the Week

1960s

In 1966, the New York Yankees, who in the year before played 21 Games of the Week for CBS, joined NBC's package, as did the Philadelphia Phillies. The new package under NBC called for 28 games compared to 1960's three-network combination of 123.

On October 19, 1966, NBC signed a three-year contract[2] with Major League Baseball. The year before, NBC lost the rights to the Saturday-Sunday Game of the Week. In addition, the previous deal limited CBS to covering only 12 weekends when its new subsidiary, the New York Yankees, played at home.

Under the new deal, NBC paid roughly US$6 million per year for 25 Saturday games and prime-time contests on Memorial Day, Independence Day, and Labor Day; $6.1 million for the 1967 World Series and 1967 All-Star Game; and $6.5 million for the 1968 World Series and 1968 All-Star Game. This brought the total value of the contract (which included three Monday night telecasts) up to $30.6 million.

NBC, replacing CBS, traded a circus for a seminar. Pee Wee Reese said "Curt Gowdy was its guy (1966–1975), and didn't want [Dizzy] Dean – too overpowering. Curt was nice, but worried about mistakes. Diz and I just laughed." Falstaff Brewery hyped Dean as Gowdy in return said "I said, 'I can't do "Wabash Cannonball." Our styles clash'"-then came Pee Wee Reese. Gowdy added by saying about the pairing between him and Reese "They figured he was fine with me, and they'd still have their boy."

To many, baseball meant CBS' 1955–1964 Game of the Week thoroughbred. A year later, NBC bought ABC's variant of a mule so to speak. "We had the Series and All-Star Game. 1966–1968's "Game" meant exclusivity," said NBC Sports head Carl Lindemann. Lindemann added by saying "[Colleague] Chet Simmons and liked him [Gowdy] with the Sox and football"-also, getting two network sports for the price of one. As his analyst, Gowdy wanted his friend Ted Williams. NBC's lead sponsor, Chrysler said no when Williams, a Sears spokesman, was pictured putting stuff in a Ford truck.

A black and white kinescope (saved by Armed Forces Television) of a July 12, 1969 between the Philadelphia Philles and Chicago Cubs is believed to be the oldest surviving complete telecast of the Saturday afternoon Game of the Week.

1960s ratings

The Nielsen ratings for the Game of the Week from 1966–1968 as well as the World Series fell by 10 and 19%, respectively. Only the All-Star Game nixed the seemingly growing view that baseball was too bland for a hip and inchoate age. Almost half (48%) in a 1964 Harris Poll named baseball as their favorite sport. Just 19% did a decade later, as football became more popular than baseball on television and by attendance figures. Part of the problem was that exclusivity began. Lindsey Nelson said "Think of the last decade. Mel, Buck, Diz-and one guy replaces 'em." As viewers grew tired, the Sporting News got so many unfavorable letters (mostly concerning their problems with Curt Gowdy)-"atrocity...a pallbearer...baseball is not dead, no thanks to Gowdy"-it routed them to NBC. Harry Caray wrote "As spectacle, baseball suffers on [TV]." He added by saying "The fan at the park [talk, drink, take Junior to the john] rarely notices the time span between pitches. Not to the same fan at home." Although not necessarily responsible, Gowdy was held accountable, becoming, as he did, more visible than even Dizzy Dean.

One other problem was that although the "Game Of The Week" was available in cities with Major League clubs; network telecasts often went head-to-head with local broadcasts of hometown teams, since at the time, nearly all Saturday games in the league were afternoon contests. Given a choice of watching the hometown team or a network "Game Of The Week", most fans would pick the former.

1970s

In 1976, NBC paid US$10.7 million per year to show 25 Saturday Games of the Week and the other half of the postseason (the League Championship Series in odd numbered years and World Series in even numbered years). NBC would continue this particular arrangement with ABC through 1989.

Joe Garagiola was pushed to succeed Curt Gowdy, who by 1978 was reduced to being a roving World Series reporter, as NBC's #1 play-by-play announcer (and team with color commentator Tony Kubek) in 1976. NBC hoped that Garagiola's charm and unorthodox dwelling on the personal would stop a decade-long ratings dive for the Game of the Week. Instead, the ratings bobbed from 6.7 (1977) via 7.5 (1978) to 6.3 (1981–1982). "Saturday had a constituency but it didn't swell" said NBC Sports executive producer Scotty Connal. Some believed that millions missed Dizzy Dean while local-team TV split the audience.

Scotty Connal believed that the team of Joe Garagiola and Tony Kubek were "A great example of black and white." Connal added by saying "A pitcher throws badly to third, Joe says, 'The third baseman's fault.' Tony: 'The pitcher's'" Media critic Gary Deeb termed theirs "the finest baseball commentary ever carried on network TV."

In late 1979, Milwaukee Brewers announcer Merle Harmon left Milwaukee completely in favor of a multi-year pact with NBC. Harmon saw the NBC deal as a perfect opportunity since according to The Milwaukee Journal he would make more money, get more exposure, and do less traveling. At NBC, Harmon did SportsWorld, the backup Game of the Week, and served as a field reporter for the 1980 World Series. Harmon most of all, had hoped to cover the American boycotted 1980 Summer Olympics from Moscow. After NBC pulled out of their scheduled coverage of the 1980 Summer Olympics, Harmon considered it "a great letdown." To add insult to injury, NBC fired Harmon in 1982 in favor of Bob Costas. Incidentally, long time NBC Game of the Week announcer Curt Gowdy replaced Harmon, who was working with ABC a year earlier.

1980s

On September 26, 1981, the scheduled Major League Baseball Game of the Week between the Detroit Tigers and Milwaukee Brewers had ended, and the NBC affiliate in Buffalo, New York, WGR-TV (now WGRZ), picked up the network's backup game, a Houston Astros–Los Angeles Dodgers contest in which Nolan Ryan was pitching his lone National League no-hitter. However, the coverage suddenly ended just as the ninth inning started, when the local station cut away to regular programming. WGR-TV felt duty-bound to present a naval training film--Life Aboard an Aircraft Carrier. (Baseball Hall of Shame 2 (1986), by Nash and Zullo; pp. 108–09)

By 1983, Joe Garagiola had stepped aside from the play-by-play duties for Vin Scully while Tony Kubek was paired with Bob Costas on NBC telecasts. The New York Times observed the performance of the team of Scully and Garagiola by saying "The duo of Scully and Garagiola is very good, and often even great, is no longer in dispute." A friend of Garagiola's said "He understood the cash" concerning NBC's 1984–1989 407% Major League Baseball hike. At this point the idea was basically summarized as Vin Scully "being the star" whereas, Joe Garagiola was Pegasus or NBC's junior light.

When NBC inked a US$550 million contract for six years in the fall of 1982, a return on the investment so to speak demanded Vin Scully to be their star baseball announcer. Vin Scully reportedly made $2 million a year during his time with NBC in the 1980s. NBC Sports head Thomas Watson said about Scully "He is baseball's best announcer. Why shouldn't he be ours?" Dick Enberg, who did the Game of the Week the year prior to Vin Scully's hiring mused "No room for me. "Game" had enough for two teams a week."

Vin Scully had to wait over 15 years to get his shot at calling the Game of the Week. Prior to 1983, Scully only announced the 1966 and 1974 World Series for NBC (during the time-frame of NBC having the Game of the Week) since they both involved Scully's Dodgers. Henry Hecht once wrote "NBC's Curt Gowdy, Tony Kubek, and Monte Moore sounded like college radio rejects vs. Scully."

When Tony Kubek first teamed with Bob Costas in 1983, Kubek said "I'm not crazy about being assigned to the backup game, but it's no big ego deal." Costas said about working with Kubek "I think my humor loosened Tony, and his knowledge improved me." The team of Costas and Kubek proved to be a formidable pair. There were even some who preferred the team of Kubek and Costas over the musings of Vin Scully and the asides of Joe Garagiola.[3]

One of Bob Costas and Tony Kubek's most memorable broadcasts came on June 23, 1984. The duo were at Chicago's Wrigley Field to call an unbelievable 12–11 contest between the Chicago Cubs and St. Louis Cardinals. Led by second baseman Ryne Sandberg, the Cubs rallied from a 9–3 deficit before winning it in extra innings. After Sandberg hit his second home run in the game (with two out in the bottom of the 9th to tie it 11–11), Costas cried "That's the real Roy Hobbs because this can't be happening! We're sitting here, and it doesn't make any difference if it's 1984 or '54-just freeze this and don't change a thing!"

In 1985, NBC got a break when Major League Baseball dictated a policy that no local game could be televised at the same time that a network "Game Of The Week" was being broadcast. Additionally, for the first time, NBC was able to feed the "Game Of The Week" telecasts to the two cities whose local teams participated. In time, MLB teams whose Saturday games were not scheduled for the "Game Of The Week" would move the start time of their Saturday games to avoid conflict with the NBC network game, and thus, make it available to local television in the team's home city (and the visiting team's home city as well).

The end of an era

On December 14, 1988, CBS (under the guidance of Commissioner Peter Ueberroth,[4] Major League Baseball's broadcast director Bryan Burns,[5] CBS Inc. CEO Laurence Tisch as well as CBS Sports executives Neal Pilson and Eddie Einhorn) paid approximately US$1.8 billion[5] for exclusive over-the-air television rights for over four years (beginning in 1990[6]). CBS paid about $265 million each year for the World Series, League Championship Series, All-Star Game, and the Saturday Game of the Week.

NBC's final Game of the Week was televised on October 9, 1989. It was Game 5 of the National League Championship Series between the San Francisco Giants and Chicago Cubs from Candlestick Park. At the end of the telecast, game announcer Vin Scully said "It's a passing of a great American tradition. It is sad. I really and truly feel that. It will leave a vast window, to use a Washington word, where people will not get Major League Baseball and I think that's a tragedy. It's a staple that's gone. I feel for people who come to me and say how they miss it, and I hope me."

Bob Costas said "Who thought baseball'd kill its best way to reach the public? It coulda kept us and CBS-we'd have kept the "Game"-but it only cared about cash." Costas added that he would rather do a Game of the Week that got a 5 rating than host a Super Bowl. "Whatever else I did, I'd never have left "Game of the Week"" Costas claimed.

The final regular season edition of NBC's Game of the Week was televised on September 30, 1989. That game featured the Toronto Blue Jays beating Baltimore Orioles 4–3 to clinch the AL East title from the SkyDome. It was the 981st edition of NBC's Game of the Week overall. Tony Kubek reacted by saying "I can't believe it" when the subject came about NBC losing baseball for the first time since 1947. Coincidentally, from 1977–1989, Tony Kubek (in addition to his NBC duties) worked as a commentator for the Toronto Blue Jays.

NBC's Game of the Week facts

On April 7, 1984, the Detroit Tigers' Jack Morris threw a no-hitter against the Chicago White Sox at Comiskey Park; the game was the 1984 season opener for NBC's baseball coverage, and it was the only no-hit game thrown in the series' history.

NBC's Game of the Week announcers

- Sal Bando (1982)

- Buddy Blattner (1969)

- Jack Buck (1976)

- Bob Costas (1982–1989)

- Dick Enberg (1977–1982)

- Curt Gowdy (1965–1975)

- Joe Garagiola (1974–1988)

- Merle Harmon (1980–1981)

- Charlie Jones (1977–1979)

- Sandy Koufax (1967–1972)

- Tony Kubek (1966–1989)

- Ron Luciano (1980–1981)

- Tim McCarver (1980)

- Jon Miller (1986–1989)

- Joe Morgan (1986–1987)

- Monte Moore (1978–1980, 1983)

- Bill O'Donnell (1969–1976)

- Wes Parker (1979)

- Jay Randolph (1982)

- Pee Wee Reese (1966–1968)

- Ted Robinson (1986–1989)

- Vin Scully (1983–1989)

- Tom Seaver (1989)

- Jim Simpson (1966–1977, 1979)

- Maury Wills (1973–1977)

CBS takes over (1990–1993)

CBS alienated and confused fans with their sporadic treatment of regular season telecasts.[7][8] With a sense of true continuity destroyed, fans eventually figured that they couldn't count on CBS to satisfy their needs (thus poor ratings were a result). CBS televised 16 regular season Saturday afternoon games each season (not counting back-up telecasts), which was 14 fewer than what NBC televised during the previous contract.[9] CBS used the strategy of broadcasting only a select number of games partly because the network had a substantial number of other sports commitments like college football and professional golf; and partly also in order to build a demand in response to supposedly sagging ratings. In addition, CBS angered fans by ignoring the division and pennant races; instead, their scheduled games focused on games featuring major-market teams, regardless of their record.

Marv Albert, who hosted NBC's studio baseball pre-game show for many years said about CBS' baseball coverage "You wouldn't see a game for a month. Then you didn't know when CBS came back on." Sports Illustrated joked that CBS stood for Covers Baseball Sporadically. USA Today added that Jack Buck and Tim McCarver "may have to have a reunion before [their] telecast." Mike Lupica of the New York Daily News took it a step further by calling CBS' baseball deal "The Vietnam of sports television."

NBC play-by-play man Bob Costas believed that a large bulk of the regular season coverage beginning in the 1990s shifted to cable (namely, ESPN) because CBS, the network that was taking over from NBC the television rights beginning in 1990, didn't really want the Saturday Game of the Week. Many fans who didn't appreciate CBS' approach to scheduling regular season baseball games believed that they were only truly after the marquee events (i.e. All-Star Game, League Championship Series, and the World Series) in order to sell advertising space (especially the fall entertainment television schedule).

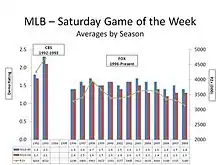

Regular season (Saturday afternoons: April–September)

| Year | Network | Rating |

| 1987 | NBC | 5.9 |

| 1988 | NBC | 5.5 |

| 1989 | NBC | 4.9 |

| 1990 | CBS | 4.7 |

| 1991 | CBS | 4.1 |

| 1992 | CBS | 3.4 |

| 1993 | CBS | 3.4 |

Hiatus period (1994–1995)

In 1994 and 1995, there was no traditional Saturday Game of the Week coverage. In those two seasons, The Baseball Network (a joint venture by MLB, NBC and ABC) utilized a purely regional schedule of 12 games per week that could only be seen based on the viewer's local affiliate.

The Fox era (1996–present)

Major League Baseball made a deal with the Fox Broadcasting Company on November 7, 1995. Fox paid a fraction less of the amount of money that CBS paid for the Major League Baseball television rights for the 1990–1993 seasons. Unlike the previous television deal, "The Baseball Network", Fox reverted to the format of televising regular season games (approximately 16 weekly telecasts that normally began on Memorial Day weekend) on Saturday afternoons. Fox did however, continue a format that "The Baseball Network" started by offering games based purely on a viewer's region. Fox's approach has usually been to offer four regionalized telecasts, with exclusivity from 1:00 to 4:00 P.M. in each time zone. When Fox first got into baseball, it used the motto "Same game, new attitude." It was also used when the network acquired the partial broadcast rights to the National Football League two years earlier.

Like NBC and CBS before it, Fox determined its Saturday schedule by who was playing a team from one of the three largest television markets: New York City, Los Angeles, or Chicago. If there was a game which combined two of these three markets, it would be aired.

In Fox's first season of Major League Baseball coverage in 1996, they averaged a 2.7 rating for its Saturday Game of the Week. That was down 23% from CBS' 3.4 in 1993 despite the latter network's infamy for its rather haphazard Game of the Week schedule.

In 2004, Fox's Game of the Week telecasts only appeared three times after August 28, due to ratings competition from college football (especially since Fox affiliates may have had syndicated college football broadcasts). One unidentified former Fox broadcaster complained by saying "Fox is MIA on the pennant race, and Joe [Buck] doesn't even do [September 18's] Red Sox-Yankees. What kind of sport would tolerate that?" By this point, Joe Buck was unavailable to call baseball games, since he became Fox's #1 NFL announcer (a job he has held since 2002). The following two seasons saw similar interruptions in Fox's September coverage.

One of the terms of the deal was that, beginning with the 2007 season, the Saturday Game of the Week coverage was extended over the entire season rather than starting after Memorial Day, with most games being aired in the 3:30–7:00 p.m. (EDT) time slot, changed to 4:00 to 7:00 after Fox cancelled its in-studio pre-game program for the 2009 season. Exceptions were added in 2010 with 3:00 to 7:00 for Saturday afternoons where Fox would broadcast a NASCAR Sprint Cup Series race in prime time (which starts at 7:30) and 7:00 to 10:00, when Fox broadcasts the UEFA Champions League soccer final (which starts at 3:00).

For 2012, Fox revised its schedule. While the 3:30 p.m. EDT starting time continues, weekly games on Saturday NASCAR race dates in Texas, Richmond, and Darlington, start at 12:30 p.m. EDT. And starting with the UEFA Champions League Final Match Day until the Saturday before the All-Star Break, all Game of the Week games would start at 7 p.m. EDT. The Baseball Night in America moniker was used for all MLB on Fox games in that span.

In 2014, the Fox Sports 1 cable network began airing regular-season games over 26 Saturdays. As a result, MLB regular season coverage on the over the air Fox network was reduced to 12 weeks.

Fox's regular season ratings (Saturday afternoons: 1996–present)

| Year | Rating |

| 1996 | 2.7 |

| 1997 | 2.7 |

| 1998 | 3.1 |

| 1999 | 2.9 |

| 2000 | 2.6 |

| 2001 | 2.6 |

| 2002 | 2.5 |

| 2003 | 2.7 |

| 2004 | 2.7 |

| 2005 | 2.6 |

| 2006 | 2.4 |

| 2007 | 2.3 |

| 2008 | 2.0 |

| 2009 | 1.8 |

| 2010 | 1.8 |

| 2011 | 1.8 |

| 2012 | 1.7 |

| 2013 | 1.6 |

| 2014 | 1.3 |

| 2015 | 1.4 |

| 2016 | 1.3 |

| 2017 | 1.3 |

| 2018 | 1.4 |

| 2019 | 1.5 |

The Game of the Week on radio

From 1985 to 1997, the CBS Radio network aired its own incarnation of the Game of the Week, broadcasting games at various times on Saturday afternoons and/or Sunday nights. In 1998, national radio rights went to ESPN Radio, which airs Saturday afternoon games during the season as well as Sunday Night Baseball and Opening Day and holiday broadcasts.

Earlier, the Mutual and Liberty networks had aired Game of the Day broadcasts to non-major-league cities in the late 1940s and 1950s.

CBS

- Joe Buck (1993–1995)

- Gary Cohen (1986; 1994–1997)

- Jerry Coleman (1985–1997)

- Gene Elston (1987–1995)

- Curt Gowdy (1985–1986)

- Hank Greenwald (1997)

- Ernie Harwell (1992–1997)

- Jim Hunter (1986–1996)

- Bob Murphy (1985–1986; 1988)

- John Rooney (1985–1997)

- Lindsey Nelson (1985–1986)

- Bill White (1985–1989)

ESPN

- Dave Campbell (1999–2010)

- Kevin Kennedy (1998)

- Jon Sciambi (2010–present)

- Dan Shulman (2002–2007)

- Chris Singleton (2011–present)

- Charley Steiner (1998–2001)

- Rick Sutcliffe (1999)

- Gary Thorne (2008–2009)

Liberty

Mutual

- Bud Blattner (1952; 1954)

- Dizzy Dean (1951–1952)

- Gene Elston (1958–1960)

- Al Helfer (1950–1954)

- Van Patrick (1960)

A Games and B Games

The A Game is generally the nickname for the baseball game that is broadcast to approximately 80% of the country. The B Game (also known as the Backup Game) only aired in the participants' home markets. For example, if the Cubs were playing the Cardinals, only the Chicago and St. Louis television markets would get a chance to see the game. The B Game also generally existed as a backup in case of rainouts/delays at the A Game.

Previously (i.e. pre-1980s), NBC typically had the A Game going to most of the country (but not to the markets of the participating teams). While the B Game only went to the home markets of the teams in the A Game. In those days, the TV rules did not allow a market to see its local team play on NBC. However, in situations where the B Game got rained out, the rules would relax.

In the early years of ABC's Monday Night Baseball broadcasts (c. 1976), the rules changed to allow the home market of the A Game's road team to see the A Game. Meanwhile, the A Game's home team got the B Game.

References

- Shea, Stuart (7 May 2015). Calling the Game: Baseball Broadcasting from 1920 to the Present. SABR, Inc. p. 358. ISBN 9781933599410.

- "NBC signs three-year rights deal with MLB". NBC Sports History Page. Archived from the original on 2017-08-06.

- "Costas-kubek: No. 2 On Totem Pole, No. 1 In Quality". sun-sentinel.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- Mushnick, Phil (January 29, 2007). "LOOK, BUT DON'T BLINK". New York Post. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012.

- Durso, Joseph (December 15, 1988). "A Billion-Dollar Bid By CBS Wins Rights To Baseball Games". New York Times. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017.

- CBS Sports 90 – The Dream Season promos on YouTube

- Asher, Mark (April 27, 1990). "Baseball Sells Out Fans As CBS Bucks Tradition". The Washington Post. p. B2.

- Smith, Curt (October 1, 1989). "VIEWS OF SPORT; Fight Baseball's TV Fadeout". New York Times. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017.

- Smith, Curt (April 17, 1989). "It's Going, Going, Going..." Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on May 27, 2013.