Battle for Height 776

The Battle for Height 776, part of the larger Battle of Ulus-Kert, was an engagement in the Second Chechen War that took place during fighting for control of the Argun River gorge in the highland Shatoysky District of central Chechnya, between the villages of Ulus-Kert and Selmentausen.

| Battle for Height 776 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Chechen War | |||||||

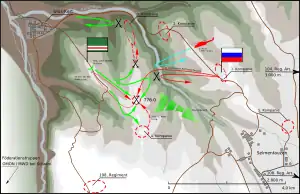

Map of the breakthrough, including the fight at the Height 776 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Disputed First day; 1000+ (per Russia) Subsequently; 1500-2000+ (per Russia) | 90[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 400–700[3] killed (per Russia) | 84 killed[2] | ||||||

| Note: Their respective official figures according to the both sides involved in direct combat at Height 776 (not the entire operation of the breakthrough from the Argun Gorge, which also included other skirmishes in the area ). | |||||||

In late February 2000, the Russian military attempted to surround and destroy a large Chechen separatist force (including many foreign fighters) withdrawing from the Chechen capital Grozny to Shatoy and Vedeno in the southern mountains of Chechnya following the 1999–2000 siege and capture of Grozny and the rebel main force's breakout from the city earlier that month.[4] On 29 February 2000, just hours after Russian Defense Minister Igor Sergeyev had assured his government that the Chechen War was over,[5] an isolated Russian force composed mainly of a company of paratroopers of the 76th Airborne Division from the city of Pskov found itself cut off by a retreating Chechen column led by Ibn Al-Khattab,[6] commander of foreign fighters in Chechnya. After heavy close-quarters overnight fighting, the Russian positions on the hill were overrun and most of the soldiers were killed.

Uncertainty continues to surround many aspects of the engagement, including the number of combatants, casualties, how much artillery support and close air support was provided, and how long the battle even lasted.

Battle

The goal of a regimental combat group task force of the Russian Airborne Troops (VDV) tactical group in the area, based on the 104th Guards Airborne Regiment of the 76th Division and including also teams from the GRU Spetsnaz, and the elite Vympel group of the FSB, was to block an exit from a gorge, while other Russian forces attempted to encircle a large Chechen force departing the village of Ulus Kert. The 6th Company, part of the regiment's 2nd Battalion, was part of this blocking force. The company's nominal commander was Major Sergey Molodov; however, it was actually led personally by Lieutenant Colonel Mark Yevtyukhin, commander of the entire battalion. With him were a reconnaissance platoon and an artillery forward observer team led by Captain Viktor Romanov.[1]

At dawn of 29 February, in dense fog, the Russians were surprised by a large-scale Chechen breakthrough and were attacked from their rear by a reconnaissance group of about 20 rebel fighters, soon joined by many more who then had them surrounded. After suffering heavy losses (including the death of Major Molodov) from the initial ambush, the rest of the Russians retreated to a hilltop designated Height 776, where they hastily dug defensive positions. They received fire support, including from the regimental artillery battalion's 2S9 Nona self-propelled 120 mm mortars; however, a pair of Mil Mi-24 attack helicopters reportedly turned back after being shot at en route.[7] The only Russian reinforcement that made it to Height 776 were 14 men of the 4th Company's third platoon, personally led by the battalion's deputy commander, Major Alexander Dostavalov. Attempts by the 1st and 3rd Companies, as well as the rest of the 4th Company, to rescue their surrounded comrades or to stop the breakthrough were largely unsuccessful. Eventually, badly wounded Captain Romanov allegedly called for fire support on his own position before being overrun in the final Chechen attack. According to the Russians, 84 of their soldiers were killed in combat at Height 776, including all of the officers. Only six rank-and-file soldiers survived the battle, four of them injured.[1][8]

Controversies

The battle embarrassed Russian military officials, who attempted to downplay or conceal the casualties they had suffered. Senior military leaders (including Marshal of the Russian Federation Igor Sergeyev,[5] VDV commander General Georgy Shpak,[4][9] and the commander of federal forces in Chechnya, General Gennady Troshev[10]) initially insisted that only 31 of their men were killed in the battle and denied the unofficial rumours of 86 dead. Sergey Yastrzhembsky, Russian President Vladimir Putin's spokesman on Chechnya, also claimed 31 fatalities were "the total losses of that company for several days".[11] After days of denials, Russian officials eventually admitted the losses, some of them apparently caused by friendly fire from their own artillery.[12] Russian newspapers reported that Marshal Sergeyev had ordered the losses to be covered up,[13] as the loss came just a week after 25 men from the 76th Airborne Division were killed in another battle in Chechnya.[14] Even after the figure of "at least 85" killed has been confirmed by Sergeyev, VDV deputy commander Nikolai Staskov said they were killed over four days, from 29 February to 3 March.[15] According to one source, "unofficially the losses sustained by Russian paratroopers on 1 March are blamed [by the Russian command] on the decision of the Eastern group's commander Gen. Sergey Makarov and the VDV tactical group's commander Aleksandr Lentsov."[16] The final figure ultimately stood at 84. However the total Russian strength and the losses among the other Russian units operating in the area of Ulus-Kert were never officially disclosed.

In the first days after the battle, Gen. Troshev said 1,000 rebel fighters were involved.[10] This figure was subsequently raised to 1,500–2,000 by Yastrzhembsky[4] and eventually to 2,500 by Troshev.[15] However, according to a statement by Colonel General Valery Manilov, first deputy chief of the Russian General Staff, there were only 2,500 to 3,500 separatist fighters left in all of Chechnya at this time.[17] According to Yastrzhembsky on 6 March, some 70 rebels had laid down their arms at what he called a "pocket" at Selmentausen, while "up to 1,000 might have succeeded in escaping".[4] The very first Russian official statements mentioned the death of 100 Chechen fighters at the price of 31 Russian soldiers. According to the article in Krasnaya Zvezda (Red Star), the official newspaper of the Russian Ministry of Defense, separatist casualties in the Argun Gorge area totaled approximately 400 dead, including 200 bodies allegedly found at Height 776.[1] However, the official federal estimate was later raised to about 500 enemy dead, according to the Russian government website,[18] and in 2008 the state-controlled English-language TV station Russia Today spoke even of over 700 fighters killed there.[2]

On 10 March, Chechen President Aslan Maskhadov announced a general order to begin "an all-out partisan war"[13] and the separatist forces remaining in the still unoccupied territories scattered to launch a long guerrilla war. The Russians thus lost one of their last chances to defeat a large number of the pro-independence fighters in a concentrated position, although in March the federal forces managed to inflict devastating losses against a different column of some 1,000–1,500 fighters (trapping the group under Ruslan Gelayev in the village of Komsomolskoye on 6 March and then killing hundreds of them in the following siege).

While there were no civilians in the immediate proximity of the clashes at the uninhabited Height 776, there were severe civilian casualties during the struggle for the broader Argun Gorge area, in particular from the artillery and air attacks on Ulus-Kert, Yaryshmardy and other villages, where thousands of locals and refugees from Grozny were trapped.[13] Furthermore, there were many credible reports of direct atrocities against the population. For example, on 6 March, a group of civilians was detained by soldiers at the notorious Russian checkpoint on the road between Ulus-Kert and Duba-Yurt; 12 men from the group "disappeared" and the bodies of three of them were unearthed at the nearby village of Tangi-Chu two months later.[19] In an infamous incident later in March, a local girl, Elza Kungayeva, was abducted from her home in Tangi-Chu, then raped and strangled to death by Russian Ground Forces Colonel Yuri Budanov.

Aftermath

Later, it was seen as a glorious last stand by the paratroopers, confirming the VDV's reputation in the same way that the Battle of Camarón did for the French Foreign Legion, and the events have been quickly enshrined in heroic myth. Even though some in the Russian army view it as a defeat that could have been avoided, it is officially seen in Russia as an example of bravery and sacrifice.[20]

In 2001, Putin flew to Chechnya to visit the former battlefield.[21] In 2008, a day before Russia's Defender of the Fatherland Day, a street in Grozny was officially renamed as "84 Pskov Paratroopers Street",[2] a move that sparked further controversy in Chechnya.[6][22][23]

Awards

| Russian Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

On 12 March 2000, President Putin signed an ukaz conferring Russian state awards upon participants of the battle.[6] 63 soldiers received the Order of Courage and 22 (all 13 officers and nine enlisted men) were awarded the country's highest honorary medal and title of the Hero of the Russian Federation.[24] In comparison, only 65 medals of the Hero of the Soviet Union medal were awarded for the entire duration of the 10-year Soviet intervention in Afghanistan.

Hero of the Russian Federation recipients for this incident are:[25]

- Guard Lt. Colonel Mark Yevtyukhin †

- Guard Major Sergey Molodov †

- Guard Major Alexander Dostavalov †

- Guard Captain Roman Sokolov †

- Guard Captain Viktor Romanov †

- Guard Lieutenant Alexey Vorobyov †

- Guard Lieutenant Andrey Sherstyannikov †

- Guard Lieutenant Andrey Panov †

- Guard Lieutenant Dmitry Petrov †

- Guard Lieutenant Alexander Kolgatin †

- Lieutenant Oleg Yermakov †

- Lieutenant Alexander Ryazantsev †

- Lieutenant Dmitry Kozhemyakin †

- Guard Sergeant (contract service) Sergey Medvedev †

- Guard Sergeant (contract service) Alexander Komyagin †

- Guard Sergeant (contract service) Dmitry Grigoriyev †

- Guard Sergeant Sergey Vasilyov †

- Guard Sergeant Vladislav Dukhin †

- Guard Corporal (contract service) Alexander Lebedev †

- Guard Corporal Alexander Gerdt †

- Guard Private Alexey Rasskaza †

- Guard Sergeant Alexander Suponinsky (survivor, interview in Russian)

In popular culture

A series of Russian productions loosely based on these events were produced in the years after the battle, including a 2004 theatrical musical show,[26] the 2004 television series Chest imeyu ("I Have the Honour"), the 2006 four-part television film Grozovye vorota ("The Storm Gate")[27] and the 2006 movie Proriv ("Breakthrough").[20]

See also

- Battle for Hill 3234, a successful defense of the Soviet paratroopers against an attack by the Afghan mujahideen in 1988

References

- U.S. Army Combined Arms Center (July 2001) ULUS-KERT: An Airborne Company's Last Stand

- Russia Today TV (23 February 2008) 'Miracle resistance' remembered in Chechnya Archived 28 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Забытый подвиг 6 роты [Forgotten Feat of 6 Companies] (in Russian). Эксперт. 1 March 2014.

- BBC News (6 March 2000) Chechen rebels besieged

- The Independent (15 March 2000) Nation grieves for lost paratroops of Pskov

- The Moscow Times (19 March 2008) Fairy Tales of Glorious Battles in Chechnya

- (in Russian) «Мы шли на помощь шестой роте...» – Army.lv

- (in Russian) ArtOfWar. Фарукшин Раян. 6 рота: Герой России Александр Супонинский

- RFE/RL (7 March 2000) Chechnya: Russia Provides Conflicting Reports On Casualties

- CBC News (7 March 2000) 31 Russian soldiers killed in Chechnya battles

- GlobalSecurity.org (6 March 2000) On The Situation in the North Caucasus

- Chicago Sun-Times (12 March 2000): Russians confirm troop deaths 84 fatalities in worst battle of war with Chechen rebels

- The Guardian (11 March 2000): No way back: Refugees stranded as Chechnya declares all-out war

- The Jamestown Foundation (11 May 2006) Putin address conceals challenges in the North Caucasus (Archived 15 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine)

- The Independent (10 March 2000): Russia claims rout of rebels in mountain area, but fighting continues

- Venik's Aviation (7 March 2000) War in Chechnya – 1999 Archived 21 April 2001 at the Wayback Machine (Internet Archive)

- BBC News (10 March 2000): Russia admits heavy losses

- Russian Embassy to Thailand (undated): CHECHNYA: QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS Archived 24 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Human Rights Watch (March 2001): THE "DIRTY WAR" IN CHECHNYA: FORCED DISAPPEARANCES, TORTURE, AND SUMMARY EXECUTION; The "Disappearance" of Nineteen People at the Checkpoint Between Duba-Yurt and Chiri-Yurt (13 January, 18 February and 6 March 2000)

- The Independent (15 May 2006) Kremlin film makes heroes out of paratroops it left to be massacred

- The Moscow Times (16 April 2001) Putin Takes Quick Trip to Chechnya

- Prague Watchdog (29 January 2008) Enemy Street

- Prague Watchdog (22 February 2008) Grozny street renamed in honour of Pskov paratroopers

- Russia Mourns Ambushed Troops – CBS News

- (in Russian) Евтюхин Марк Николаевич

- Gazeta.ru (18 June 2004) Bizarre Chechen War Musical Hits Moscow Stage

- AFP (21 February 2006) Russians see 'realistic' Chechnya war film, minus the reality

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle for Height 776. |

- "ULUS-KERT: An Airborne Company's Last Stand" (July 2001 U.S. Army Combined Arms Center paper based on the article in Red Star)

- Chechnya: Two Federal Disasters, Conflict Studies Research Centre, April 2002 (based mostly on General Troshev's memoir)

- (in Russian) Photos of members of the 6th Company