Battle of Cane Hill

The Battle of Cane Hill (also known as the Engagement at Cane Hill) was fought during the American Civil War on November 28, 1862, in northwestern Arkansas, near the town of Cane Hill. Union troops under Brig. Gen. James G. Blunt had entered northwestern Arkansas, and Major General Thomas Hindman of the Confederate Army sent a force under John S. Marmaduke to Cane Hill to intercept Blunt. Blunt attacked on November 28, and quickly broke Marmaduke's first line. An effective rear guard action by Joseph O. Shelby allowed the Confederates to form a second position on Reed's Mountain, but Blunt also broke this line, with the help of his artillery. Blunt's Union troops pursued the retreating Confederates, and darkness ended the action. The battle set the stage for the Battle of Prairie Grove, which occurred the next month.

| Battle of Cane Hill Engagement at Cane Hill | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

James G. Blunt William F. Cloud |

John S. Marmaduke Joseph O. Shelby | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,000 | 2,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 41–44 | 45–c. 80 | ||||||

Background

After driving a Confederate army commanded by Earl Van Dorn and Sterling Price from northwestern Arkansas in 1862 at the Battle of Pea Ridge, Union general Samuel R. Curtis was promoted to Major General and assigned to command the Department of the Missouri. Curtis replaced John M. Schofield.[1] In October of the same year, Curtis formed a new army named the Army of the Frontier and appointed Schofield to command it. Schofield's new army was composed of three divisions, commanded by James G. Blunt, James Totten, and Francis J. Herron.[2] Opposing Schofield was the command of Confederate Thomas Hindman. On May 31, 1862, Hindman had been assigned to command the Trans-Mississippi Department, but he was later relieved of command because his strict control of the region angered prominent Arkansas civilians. Hindman was replaced by Theophilus Holmes.[3] Despite his replacement as department commander, Hindman retained a field command and formed a serviceable army out of the scattered Confederate troops in the region.[4]

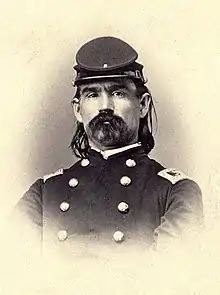

| Key Union commanders |

|---|

|

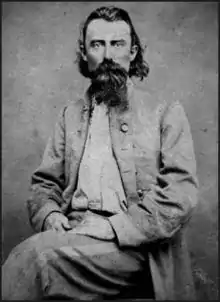

| Key Confederate commanders |

|

In early November, Herron's and Totten's divisions were stationed near Springfield, Missouri, while Blunt's division was south of Bentonville, Arkansas. A Confederate cavalry force under Emmett MacDonald had reached Cane Hill, Arkansas. Blunt was informed of MacDonald's presence, and sent a small force under Colonel William F. Cloud to confront MacDonald. After a brief clash, MacDonald's horsemen retreated.[5] After Cloud's force left the area, Hindman sent Brigadier General John S. Marmaduke with 2,000 cavalrymen to reoccupy Cane Hill. Union intelligence soon learned of the movement.[6] Cane Hill was a smaller plateau within the larger Ozark Plateau, and this high ground provided a position for Marmaduke to base his lines on. Once Marmaduke learned that Blunt was approaching his position, Marmaduke prepared for battle and sent his supply train away towards relative safety.[7]

Battle

After learning that Marmaduke had advanced to Cane Hill, Blunt moved south to confront him with 5,000 men.[8] Marmaduke countered Blunt's advance by moving a brigade under Colonel Joseph O. Shelby, including Quantrill's Raiders, forward to block the road Marmaduke expected Blunt to advance down.[9] In addition to Shelby's brigade, Marmaduke's force also contained a brigade commanded by Colonel Charles A. Carroll.[10]

However, Blunt approached along a different road than anticipated by the Confederates, creating an element of surprise. A brief artillery duel segued into an infantry assault by Blunt's force, with Cloud's brigade as the spearhead doing the most damage. The initial Confederate position had to be abandoned.[11] Besides his numerical advantage, Blunt had a sizable advantage in material, contributing to the collapse of the Confederate line. Blunt had 30 cannons with his force, while Shelby had four and Carroll an additional two. A substantial part of the Confederate force was also armed only with shotguns, while the Union had substantially better weapons.[12]

The collapse of this initial Confederate position rendered the position of Carroll's brigade unsustainable, and Carroll's Arkansas cavalry fell back.[13] With Carroll's brigade in collapse, Shelby organized a rear guard in order to keep Blunt at bay until the Confederates could retreat to a better position. Shelby divided his force into small segments, and then organized them in a successive line along the path of retreat. As Blunt pursued the retreating Confederates, the Union forces would run into one of Shelby's segments, which would hold Blunt's much-stronger force off for as long as possible. Once each position became untenable, the segment would retreat and Blunt would reach the next one. This system worked long enough to enable the Confederates to form a general secondary line. The broken nature of some of the ground the Union army had to move over also slowed Blunt's pursuit.[14]

Marmaduke's attempt to form a secondary line was abandoned after another brief artillery duel, due to the fact that Blunt's cannons had a clear advantage over Marmaduke's.[15] After falling back from that position, Marmaduke formed another defensive line at Reed's Mountain.[16] Reed's Mountain was a locally prominent height noted for the lack of vegetation on its slopes, providing an open space where Marmaduke could better align his artillery.[17] Again, Union artillery fire wreaked havoc in the Confederate line, although Blunt also order an infantry assault by the 11th Kansas and the Third Indian Home Guard. The Confederates began to run out of ammunition for both their artillery and cavalry, and one of the Confederate cannons was damaged to the extent that it was no longer usable.[16] The Confederates were forced to fall back from that position as well, and were pursued by Blunt. Again, the broken nature of some of the ground along the path of the Confederate retreat slowed the Union pursuit. Eventually, darkness ended the fighting.[18]

Aftermath

The number of casualties incurred by each side are not known for certain. One historian places Blunt as suffering eight men killed and 36 wounded, for a total of 44 casualties and Marmaduke at ten killed and a minimum of 70 wounded and missing, for a total of at least 80.[19] However, other sources place Blunt's casualties at a total of 41 and Marmaduke's at a total of 45.[20] Blunt claimed victory, although the escape of Marmaduke's command in relatively good order allowed the Confederates to view the action as only a setback.[19] Blunt remained in the Cane Hill area after the battle, while Marmaduke retreated to Van Buren, Arkansas.[20]

While Blunt was encamped at Cane Hill after the battle, the Army of the Frontier's two other divisions, Totten's and Herron's, were still in the Springfield area, roughly 100 miles away. Deep in enemy territory, Blunt had a tenuous supply line, and the distance to Springfield would mean that reinforcements would take some time to reach his position. With Blunt isolated, Hindman decided to move his army north to attack Blunt at Cane Hill before Herron could arrive with the other two Union divisions. However, Herron sent the two divisions on a hard march, and the Union reinforcements reached Blunt around the same time as Hindman's army did. This resulted in the Battle of Prairie Grove, in which the combined forces of Herron and Blunt fought Hindman to a standstill. However, lack of ammunition and reinforcements forced Hindman to retreat, giving the Union control of northwestern Arkansas.[21]

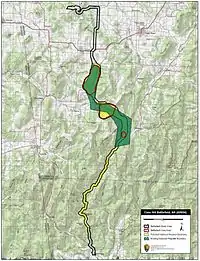

Battlefield preservation

A significant portion of the battlefield, about 5,750 acres (2,330 ha), was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1994 as the Cane Hill Battlefield.[22] The Arkansas Civil War Centennial Commission erected a highway marker near the battle site to interpret the fighting.[23] In addition to the marker, a driving tour explaining the Cane Hill battlefield has been developed.[24]

References

- Shea 2009, pp. 20–21.

- Shea 2009, p. 29.

- Shea 2009, pp. 4–9.

- Shea 2009, pp. 12–14.

- Shea 2009, pp. 64–69.

- Shea 2009, p. 70.

- Shea 2009, p. 93.

- Shea 2009, pp. 92–93.

- Shea 2009, pp. 93–94.

- O'Flaherty 1954, p. 138.

- Shea 2009, pp. 95–98.

- Shea 2009, pp. 92–99.

- Shea 2009, p. 99.

- O'Flaherty 1954, pp. 140–142.

- Shea 2009, pp. 99–100.

- Shea 2009, pp. 100–102.

- O'Flaherty 1954, p. 142.

- Shea 2009, pp. 102–104.

- Shea 2009, pp. 104–106.

- Kennedy 1998, p. 140.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 141–143.

- "National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form: Cane Hill Battlefield" (PDF). arkansaspreservation.com. United States Department of the Interior. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- Weeks 2009, pp. 46–47.

- Thompson, Alan. "Arkansas Battlefield Update". arkansaspreservation.com. Arkansas Historic Preservative Program. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

Sources

- Kennedy, Frances H. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- O'Flaherty, Daniel (1954). General Jo Shelby. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4878-6.

- Shea, William L. (2009). Fields of Blood: The Prairie Grove Campaign. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3315-5.

- Weeks, Michael (2009). The Complete Civil War Road Trip Guide. Woodstock, Vermont: The Countryman Press. ISBN 978-0-88150-860-4.

.jpg.webp)