Battle of Little Blue River

The Battle of Little Blue River was fought on October 21, 1864, as part of Price's Raid during the American Civil War. Major General Sterling Price of the Confederate States Army had led an army into Missouri in September 1864 with hopes of challenging Union control of the state. During the early stages of the campaign, Price abandoned his plan to capture St. Louis and later his secondary target of Jefferson City. The Confederates then began moving westwards, brushing aside Major General James G. Blunt's Union force in the Second Battle of Lexington on October 19. Two days later, Blunt left part of his command under the command of Colonel Thomas Moonlight to hold the crossing of the Little Blue River, while the rest of his force fell back to Independence. On the morning of October 21, Confederate troops attacked Moonlight's line, and parts of Brigadier General John B. Clark Jr.'s brigade forced its way across the river. A series of attacks and counterattacks ensued, with neither side able to gain a significant advantage.

| Battle of Little Blue River | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War | |||||||

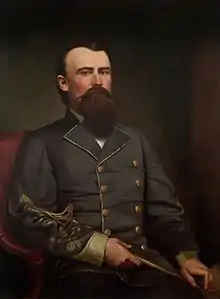

Brigadier General Joseph O. Shelby was a key Confederate commander at Little Blue River | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Samuel R. Curtis James G. Blunt Thomas Moonlight |

Joseph O. Shelby M. Jeff Thompson Colton Greene | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,800 | 5,500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| At least 20 | At least 34 | ||||||

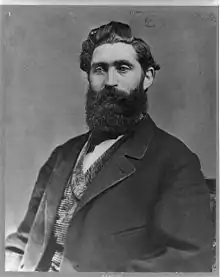

Meanwhile, Blunt had received permission from Curtis to make a stand at the Little Blue River, and he and Curtis returned to the field, bringing reinforcements that brought total Union strength up to about 2,800 men. More Confederate soldiers from the divisions of Brigadier Generals Joseph O. Shelby and John S. Marmaduke arrived on the field, bringing Confederate strength to about 5,500 men. One regiment of Confederate cavalry threatened the Union flank, and Brigadier General M. Jeff Thompson's Confederate brigade pressed the Union center. The Union line fell back, with the fighting largely ending around 16:00, when the Union troops reached Independence. The Union soldiers later fell back to the Big Blue River, abandoning Independence.

The next day Union soldiers commanded by Major General Alfred Pleasonton forced their way across the Little Blue River and retook Independence from the Confederates during the Second Battle of Independence. On October 23, the Confederates were defeated by Curtis and Pleasonton at the Battle of Westport, which forced Price's men to retreat from Missouri. A study published by the American Battlefield Protection Program in 2011 determined that the Little Blue River battlefield was in fragmented condition and was threatened by highway development. It found that part of the site was potentially eligible to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Background

At the start of the American Civil War in 1861, the state of Missouri was a slave state, but did not secede. However, the state was politically divided: Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson and the Missouri State Guard (MSG) supported secession and the Confederate States of America, while Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon and the Union Army supported the United States and opposed secession.[2] Under Major General Sterling Price, the MSG defeated Union armies at the battles of Wilson's Creek and Lexington in 1861, but by the end of the year, the secessionist forces were restricted to the southwestern portion of the state by Union reinforcements. Meanwhile, Jackson and a portion of the state legislature voted to secede and join the Confederate States of America, while another element of the legislature voted to reject secession, essentially giving the state two governments.[3] In March 1862, a Confederate defeat at the Battle of Pea Ridge in Arkansas gave the Union control of Missouri,[4] and Confederate activity in the state was largely restricted to guerrilla warfare and raids throughout 1862 and 1863.[5]

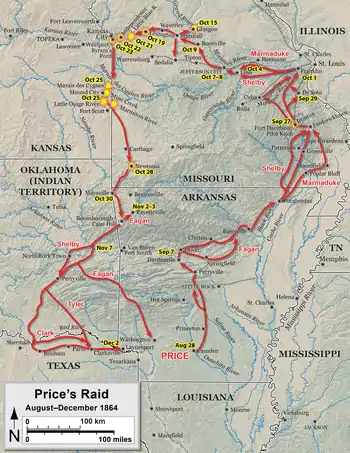

By the beginning of September 1864, events in the eastern United States, especially the Confederate defeat in the Atlanta campaign, gave Abraham Lincoln, who supported continuing the war, an edge in the 1864 United States presidential election over George B. McClellan, who favored ending the war. At this point, the Confederacy had very little chance of winning the war.[6] Meanwhile, in the Trans-Mississippi Theater, the Confederates had defeated Union attackers during the Red River campaign in Louisiana, which took place from March through May. As events east of the Mississippi River turned against the Confederates, General Edmund Kirby Smith, Confederate commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department, was ordered to transfer the infantry under his command to the fighting in the Eastern and Western Theaters. However, this proved to be impossible, as the Union Navy controlled the Mississippi River, preventing a large scale crossing. Despite having limited resources for an offensive, Smith decided that an attack designed to divert Union troops from the principal theaters of combat would have an equivalent effect as the proposed transfer of troops, through decreasing the Confederates' numerical disparity east of the Mississippi. Price and the new Confederate Governor of Missouri, Thomas Caute Reynolds,[lower-alpha 1] suggested that an invasion of Missouri would be an effective offensive; Smith approved the plan and appointed Price to command the offensive. Price expected that the offensive would create a popular uprising against Union control of Missouri, divert Union troops away from principal theaters of combat (many of the Union troops previously defending Missouri had been transferred out of the state, leaving the Missouri State Militia to be the state's primary defensive force), and aid McClellan's chance of defeating Lincoln in the election.[9] On September 19, Price's column, named the Army of Missouri, entered the state.[10]

Prelude

When it entered the state, Price's force was composed of about 13,000 cavalrymen. However, several thousand of these men were poorly armed, and all 14 of the army's cannons were small-bore.[11] Countering Price was the Union Department of Missouri, under the command of Major General William S. Rosecrans, who had fewer than 10,000 men on hand, many of whom were militiamen.[12] In late September, the Confederates encountered a small Union force holding Fort Davidson near the town of Pilot Knob. Attacks against the post in the Battle of Pilot Knob on September 27 failed, and the Union garrison abandoned the fort that night. Price had suffered hundreds of casualties in the battle, and decided to change his objective from St. Louis to Jefferson City.[13] Price's army was accompanied by a sizable wagon train, which significantly slowed its movement.[14] The slow progress of the Confederates enabled Union forces to reinforce Jefferson City, whose garrison was increased from 1,000 men to 7,000 between October 1 and October 6.[15] In turn, Price determined that Jefferson City was too strong to attack, and began moving westwards along the course of the Missouri River. The Confederates gathered recruits and supplies during the movement; a side raid against the town of Glasgow on October 15 was successful,[1] as was another raid against Sedalia.[16]

Meanwhile, Union troops commanded by Major Generals Samuel R. Curtis and James G. Blunt were withdrawn from their role in suppressing the Cheyenne; the Kansas State Militia was also mobilized.[17] George W. Dietzler, a major general in the Kansas State Militia, was appointed as its general-in-chief, although the troops were under Curtis's authority.[18] The total strength of the mobilized militia amounted to about 15,000 men.[1] On October 15, Blunt moved his command to Hickman Mills, Missouri, where he formed it into a three-brigade division; one of the brigades was composed of Kansas militia. At this time, Price was at Marshall, east of Blunt's column. The next day, Curtis moved the Kansas militiamen to Kansas City, Missouri, but was prohibited by Thomas Carney, the governor of Kansas, from taking them east of the Big Blue River. Curtis had previously promised Carney that the militia would only travel as far as was necessary to protect Kansas. On the 17th, Blunt detached his militia brigade to Kansas City, and then sent his other two brigades to Holden.[19][20] Both the militia and Blunt's volunteers were grouped under Curtis's command as a new formation known as the Army of the Border.[21]

On October 18, Blunt's advance guard, commanded by Colonel Thomas Moonlight, occupied the town of Lexington, hoping to cooperate with a force commanded by Brigadier General John B. Sanborn to catch and trap Price. However, Sanborn's force was too far south of Lexington to move in concert with Blunt. Additionally, he learned that Price was only 20 miles (32 km) away at Waverly; he also received word from Curtis that the political authorities in Kansas would not allow him to send militiamen to Curtis.[22][23] Blunt then made the decision to reinforce his outer positions and resist the inevitable Confederate advance.[24] Shelby's men attacked the Union line at Lexington on October 19, beginning the Second Battle of Lexington, but Blunt's troops held. The Union troops retreated once Price deployed men of Major General James F. Fagan's and Brigadier General John S. Marmaduke's divisions into the fray.[22]

Battle

After the battle at Lexington, Blunt's forces fell back to the west, with Moonlight's brigade serving as the rear guard. Early on the morning of October 20, Blunt decided to halt and defend a position east of the Little Blue River. Blunt requested reinforcements from Curtis, but the latter, whose Kansas militia units would not serve east of the Big Blue River, ordered Blunt to leave a holding force at the Little Blue River and fall back to the main Union body.[25] Many of the militiamen did not want to serve outside Kansas,[1] and Carney would not allow them to be moved too far east into Missouri.[26] Blunt argued for a stand at the river but complied with his orders, falling back to Independence that evening.[25] The 11th Kansas Cavalry Regiment and four cannons, was left behind to serve as a rear guard under Moonlight's command. The strength of this force amounted to either 400[27] or 600 men.[28] Two companies of the 11th Kansas Cavalry were placed at a bridge over the river with instructions to burn it when the Confederates arrived, while single companies guarded fords, one within either 1 mile (1.6 km)[29] or 2 miles (3.2 km) north of the bridge[30] and the other 4 miles (6.4 km) to the south of the bridge.[29] The remainder of the 11th Kansas Cavalry was held as a reserve.[31] Despite these precautions, other fords closer to the bridge were left unguarded,[29] and the river was shallow enough to be crossed at many points.[30]

The Confederates struck at about 07:00 on the morning of October 21, with the advance led by Company D of the 5th Missouri Cavalry Regiment. The Confederate company lost over a third of its strength in a sharp fight with Union skirmishers, who were eventually driven across the bridge.[32][28] After Confederate pressure grew strong enough that the defenders at the bridge determined that they would not be able to hold out, they burned the bridge.[lower-alpha 2] Meanwhile, Brigadier General John B. Clark Jr.'s Confederate brigade arrived, and Marmaduke sent the 4th Missouri Cavalry Regiment to find a ford south of the bridge, while the 10th Missouri Cavalry Regiment found a crossing about halfway between the bridge and the Union company stationed north of it. The northward Union company was outflanked and retreated. Clark, in turn, ordered more of his brigade to cross behind the 10th Missouri Cavalry. However, the ford soon became congested, slowing Confederate movements.[34]

The Union troops holding the destroyed bridge also retreated, and the 11th Kansas Cavalry, with the exception of the isolated company to the south, retreated to a hilltop line marked by a stone wall. The 10th Missouri Cavalry pursued them uphill and attacked, but was repulsed in disarray by the Kansans and the fire from their repeating rifles.[35] Confederate Colonel Colton Greene was able to get his 3rd Missouri Cavalry Regiment across the ford, although the men of the 10th Missouri Cavalry fell back all the way to the river. Three cannons from Harris's Missouri Battery also crossed, and moved into a position to support Greene. The 11th Kansas Cavalry Regiment counterattacked with 600 men, while the 3rd Missouri Cavalry Regiment was only about 150 men strong. Once the combat reached close quarters, the Confederate artillery was no longer effective, as the risk of accidental friendly fire was too great. Instead, the cannoneers fired blanks in an attempt to mislead the Union troops into thinking they were under heavy artillery fire. The Kansans retreated, and Greene believed that the blank cartridge ruse had been effective. The two sides engaged in a series of counterattacks, with neither able to gain a significant advantage.[36]

Meanwhile, Blunt had been able to get permission from Curtis to fight at the Little Blue River. Blunt then began a return from Independence to the river, bringing with him not only the men who had accompanied him, but also 900 men and six cannons under the command of Colonel James H. Ford.[37][38] Back at the Little Blue River, Clark's brigade had finally gotten across the river. Around 11:00, Moonlight observed some of Shelby's men approaching in support of Clark's brigade.[39] Despite being farther from the battlefield than Fagan's division, Shelby's division was sent to the field, as it was considered more reliable.[33] Blunt's command also arrived on the field at about 11:00.[40] By then, Moonlight's force had fallen back to about 2 miles (3.2 km) from the river.[41] Between the commands of Moonlight and Blunt, there were about 2,600 Union men on the field, with the support of 15 cannons. Elements of both Marmaduke's and Shelby's divisions totaling about 5,500 men were present.[39] The Union line was held on the left by the 15th Kansas Cavalry Regiment, which was supported by five cannons. The Union line stretched to the north, with the 3rd Wisconsin Cavalry Regiment next to the 15th Kansas Cavalry, followed by the 2nd Colorado Cavalry Regiment, McLain's Colorado Battery, the 16th Kansas Cavalry Regiment, and the 11th Kansas Cavalry. Four cannons supported the 11th Kansas Cavalry. About one quarter of the Union soldiers were sent to the rear to hold the men's horses.[42] The men from both sides were deployed dismounted.[43]

The increased Union numbers began to put substantial pressure on Greene's regiment. Wood's Missouri Cavalry Battalion arrived to reinforce Greene, and aligned in an orchard. After some fighting, the Confederates began to run low on ammunition and started a retreat, which was accompanied by Harris's Battery. Just as the Confederate line was beginning to collapse, the 7th Missouri Cavalry Regiment and Davies's Missouri Cavalry Battalion arrived to shore up the line. Additionally, Brigadier General M. Jeff Thompson's brigade of Shelby's division also crossed over and deployed to the left of Clark's brigade. After Thompson's men made it across the river, Shelby also fed Colonel Sidney D. Jackman's brigade into the fight.[44] Shelby then ordered an assault against the Union line. Most of Jackman's brigade was inexperienced and made little offensive progress, but Nichols's Missouri Cavalry Regiment, which was still mounted, advanced against the Union left flank. Curtis arrived on the battlefield at 13:00,[45] accompanied by two additional cannons.[46] There were now about 2,800 Union troops on the field.[47] Curtis noticed Nichols's unit's incursion towards the Union flank, and sent McLain's Battery and two other cannons to counter the threat. However, as these cannons were taken from other parts of the Union lines, this weakened the Union center.[45]

Shelby took advantage of the weakened Union center by pressing the attack harder.[45] Thompson's men began pressing the Union line. Complicating matters for the Union soldiers was Curtis's decision to send the wagons containing additional ammunition back to Independence. With ammunition running low, Nichols's men threatening one flank, and Thompson pushing forward, the Union troops began conducting a fighting withdrawal. Blunt placed Ford in charge of the rear guard, although in practice, Moonlight shared command responsibility with Ford, whose men conducted a rear guard maneuver in which the men deployed in two ranks. The front rank resisted the Confederate pursuit until falling back behind the second rank, after which the process was repeated.[48] During the retreat, McLain's Battery was caught in an exposed position, but was rescued by a counterattack made by elements of the 11th Kansas Cavalry.[45][49] Later, these elements of the 11th Kansas Cavalry were also stuck in an exposed position and had to be rescued by a charge from the 2nd Colorado Cavalry. By 16:00, Union troops held a line near Independence and large-scale fighting ended. Later that afternoon, Blunt ordered a retreat to the Big Blue River, which was lightly pursued by the Confederates.[50] Some skirmishing occurred within Independence itself during the retreat.[41] By nightfall, Curtis's men were on the west side of the Big Blue River, and Price's army was in the Independence area.[50]

Aftermath and preservation

Official casualty numbers are only known for a few units on each side. The 11th and 15th Kansas Cavalries and the 2nd Colorado Cavalry combined for 20 men killed. On the Confederate side, the 3rd Missouri Cavalry Regiment combined for 31 killed and wounded, while a total of three men were killed between Davies's Battalion and the 10th Missouri Cavalry Regiment. Among the Union dead was Major Nelson Smith of the 2nd Colorado Cavalry, while Confederate guerrilla leader George Todd was also killed.[51] Confederate surgeon William McPheeters reported that 10 wounded Union soldiers were left in Independence, and that civilians reported about 100 more had been taken with the Union troops during the retreat. McPheeters also noted seeing the bodies of dead Union soldiers strewn along the road from the river to Independence.[52] Shelby later described the fight as the beginning of significant difficulties for his division during the campaign.[53]

The day after the battle, Price sent Shelby south of Curtis's main line along the Big Blue River. In the initial stages of the Battle of Byram's Ford, Shelby's men forced their way across a crossing of the Big Blue River, causing Curtis to order a withdrawal to Brush Creek. Meanwhile, Union cavalry commanded by Major General Alfred Pleasonton attacked Price's rear guard from the east in the Second Battle of Independence. After pushing across the Little Blue River, Pleasonton's men struck Brigadier General William L. Cabell's Confederate brigade, capturing both men and two cannons, as well as taking the town of Independence.[54] On October 23, Price's men fought the Battle of Westport, where they were defeated by Curtis's and Pleasonton's commands. The Confederates began retreating through Kansas, before reentering Missouri on October 25. Price's survivors eventually reached Texas via Arkansas and the Indian Territory, suffering several defeats along the way. Price had lost over two thirds of his men during the campaign.[55]

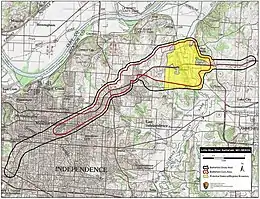

A study published by the American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP) in 2011 determined that the Little Blue River battlefield was fragmented, but that there was still potential for future preservation. However, the site was noted to be threatened by highway construction.[56] The battlefield is not listed on the National Register of Historic Places, but the ABPP found that 2,493.72 acres (1,009.17 ha) are potentially eligible for listing. At the site, 6.50 acres (2.63 ha) are currently under some form of permanent protection. There is public interpretation at the site but no visitors center.[57] The site is part of Freedom's Frontier National Heritage Area and the Civil War Roundtable of Western Missouri acts as a battlefield friends group.[58]

Notes

References

- Kennedy 1998, p. 382.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 19–20.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 20–25.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 34–37.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 377–379.

- Kennedy 1998, p. 343.

- Parrish 2001, p. 49.

- "Claiborne Fox Jackson, 1861". sos.mo.gov. Missouri State Archives. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- Collins 2016, pp. 27–28.

- Collins 2016, p. 37.

- Collins 2016, p. 39.

- Collins 2016, p. 41.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 380–382.

- Collins 2016, p. 53.

- Collins 2016, p. 54.

- Collins 2016, p. 65.

- Collins 2016, p. 61.

- Sinisi 2020, pp. 157, 160.

- Sinisi 2020, pp. 157, 161.

- Collins 2016, p. 66.

- Sinisi 2020, p. 160.

- Collins 2016, p. 67.

- Langsdorf 1964, pp. 288–289.

- Langsdorf 1964, p. 288.

- Collins 2016, pp. 70–71.

- Collins 2016, p. 71.

- Kirkman 2011, p. 83.

- Collins 2016, p. 72.

- Sinisi 2020, pp. 181–182.

- Kirkman 2011, p. 86.

- Collins 2016, p. 73.

- Monnett 1995, pp. 56–57.

- O'Flaherty 2000, p. 221.

- Sinisi 2020, p. 183.

- Sinisi 2020, pp. 183–184.

- Sinisi 2020, p. 184.

- Monnett 1995, pp. 59–60.

- Kirkman 2011, pp. 84–85.

- Collins 2016, pp. 74–75.

- Sinisi 2020, p. 186.

- Gerteis 2012, p. 196.

- Monnett 1995, pp. 60–61.

- Collins 2016, p. 77.

- Sinisi 2020, pp. 186–187.

- Collins 2016, p. 79.

- Sinisi 2020, p. 185.

- Collins 2016, p. 78.

- Sinisi 2020, pp. 187–188.

- Sinisi 2020, p. 188.

- Sinisi 2020, pp. 188–189.

- Sinisi 2020, pp. 188–190.

- Pitcock & Gurley 2002, p. 234.

- Castel 1993, p. 229.

- Kennedy 1998, p. 383.

- Kennedy 1998, pp. 383–386.

- American Battlefield Protection Program 2011, p. 9.

- American Battlefield Protection Program 2011, pp. 24–25.

- American Battlefield Protection Program 2011, pp. 26–28.

Sources

- Castel, Albert (1993) [1968]. General Sterling Price and the Civil War in the West (Louisiana Paperback ed.). Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-1854-0.

- Collins, Charles D., Jr. (2016). Battlefield Atlas of Price's Missouri Expedition of 1864 (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-940804-27-9.

- Gerteis, Louis S. (2012). The Civil War in Missouri. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1972-5.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Kirkman, Paul (2011). The Battle of Westport: Missouri's Great Confederate Raid. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-60949-006-5.

- Langsdorf, Edgar (1964). "Price's Raid and the Battle of Mine Creek" (PDF). The Kansas Historical Quarterly. Kansas State Historical Society. 30 (3). ISSN 0022-8621. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- Monnett, Howard N. (1995) [1964]. Action Before Westport 1864 (Revised ed.). Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-0-87081-413-6.

- O'Flaherty, Daniel O. (2000) [1954]. General Jo Shelby: Undefeated Rebel (reprint ed.). Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4878-6.

- Parrish, William Earl (2001) [1973]. A History of Missouri: 1860–1875. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1376-1.

- Pitcock, Cynthia DeHaven; Gurley, Bill J., eds. (2002). I Acted From Principal: The Civil War Diary of Dr. William M. McPheeters, Confederate Surgeon in the Trans-Mississippi. Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1-55728-795-3.

- Sinisi, Kyle S. (2020) [2015]. The Last Hurrah: Sterling Price's Missouri Expedition of 1864 (paperback ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-4151-9.

- "Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report on the Nation's Civil War Battlefields: State of Missouri" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: American Battlefield Protection Program. March 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2020.