Second Battle of Independence

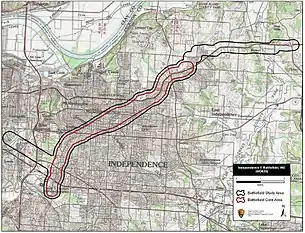

The Second Battle of Independence was a minor engagement of the American Civil War October 21–22, 1864 centered in Independence, Missouri, with some of the fiercest fighting taking place at the present-day United Nations Peace Plaza; the "Harry Truman" Railroad Depot; George Caleb Bingham's residence in the city, the Community of Christ church's Temple, Auditorium and "Stone Church"; and the headquarters of the Church of Christ (Temple Lot). The Second Battle of Independence was actually two separate battles, the first day resulting in Price's army driving Blunt's army west, out of Independence, and the second day resulting in Pleasonton's cavalry driving Price's army west, out of Independence.

| Second Battle of Independence | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Alfred Pleasonton[1] | Sterling Price | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Cavalry Division[1] | Army of Missouri | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 22,000 | 8,500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 83 |

~140 on 21st 340 on 22nd | ||||||

This clash opened the decisive phase of Confederate Maj. Gen. Sterling Price's 1864 Missouri Campaign, and culminated in his defeat at the Battle of Westport the next day, and the Battle of Mine Creek on the 25th. It was the most dramatic American Civil War action involving Jackson County, Missouri[2] since the Union's devastating "Order No. 11" a year earlier.

The battle should not be confused with the First Battle of Independence, fought in August 1862. That earlier battle resulted in a Confederate victory.

Background

The Second Battle of Independence was part of a series of battles, fought within 7 days near the Kansas-Missouri Border. These battles include battles at Lexington (Oct 19), Little Blue (Oct 21), Independence (Oct 21-22), Westport (Oct 23), Marais des Cygnes (Oct 25, also called the Battle of Osage, and the Battle of Trading Post), Mine Creek (Oct 25), and Marmiton River (Oct 25, also called Battle of Shiloh Creek or Battle of Charlot's Farm). Most of these battles were fought without adequate forage for horses, or rations for the men.

In the fall of 1864, Confederate Maj. Gen. Sterling Price was dispatched by his superior, Lt. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith, to attempt to seize Missouri for the Confederacy. Unable to attack his primary objective, St. Louis, Price decided to execute Smith's backup plan for a westward raid through Missouri and into Kansas and the Indian Territory. Their ultimate goal was to destroy or capture Union supplies and outposts, which might negatively affect Abraham Lincoln's chances for reelection in 1864.

After victories at Glasgow and Lexington, Price continued his march westward, in the direction of Kansas City and Fort Leavenworth, headquarters of the Federal Department of Kansas. His army, which he termed the Army of Missouri, was organized with Brig. Gen. Joseph Shelby's division in the lead, followed by Brig. Gen. John S. Marmaduke's division, with Brig. Gen. James Fagan's division bringing up the rear.

Union forces opposing Price consisted of militia units and the XVI Corps of Maj. Gen. Andrew J. Smith, augmented by the cavalry division of Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, detached from William S. Rosecrans's Department of Missouri. In addition, the newly activated Army of the Border under Maj. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis would engage Price's force. Curtis commanded the divisions of Maj. Gen. James G. Blunt (cavalry), Maj. Gen. George W. Dietzler (Kansas Militia Division), Pleasonton's cavalry, and two infantry divisions detached from Smith's Corps under Colonels Joseph J. Woods and David Moore—about 22,000 men in all.

Prelude

Following their defeat at Lexington, the small detachment of Union troops engaged in this battle under General Blunt retreated west toward Independence. They set up camp on October 20 behind strong defensive positions on the west bank of the Little Blue River, about five miles east of town, and awaited the main Confederate force. However Blunt's superior, General Curtis, ordered him to abandon these positions save for a small blocking force under Colonel Thomas Moonlight, and return to Independence.

October 21

The Second Battle of Independence actually commenced as a connected engagement at the Little Blue River, in the rural easternmost boundaries of the city, and involved different Union troops on each day. It began on October 21, when General Blunt was ordered to return to the Little Blue and reoccupy the same defensive positions he had been directed to abandon only the day before. Upon his arrival, he found that Colonel Moonlight had burnt the bridge over the river as previously instructed, after being attacked by Price's advance guard.

About 7 AM, General Shelby's troops arrived on the scene, and fiercely engaged the Union forces, Colonel Moonlight's troops, about 600 men and four twelve-pound mountain howitzers. Witnesses reported that the Federals entrenched themselves behind rock walls, and forced attacking Confederates to fight for nearly every inch of ground. At this time, General Blunt's 1st Division, along with Colonel James Ford's Fourth Brigade were brought in as reinforcements. The Fourth Brigade consisted of the 2nd Colorado and 16th Kansas cavalries, and the Colorado Battery, about 900 men with six guns.[3]

At 10 AM, the Union troops were compelled to give way, retreating west through Independence toward Westport. The 1st and 4th Brigades leaving the fight at Independence, joining the fight at the Big Blue, eight miles away.[3] Union rearguard units attempted to impede Price's progress throughout the afternoon of the 21st, as brisk fighting raged through the streets of the city, but all were ultimately compelled to withdraw. Price's troops halted their advance at an unfinished railroad cut on the western side of town's center, and made camp there for the evening.[4]

At some later point in time, General Blunt arrived, and had the troops form a new line of battle. At this time, the 11th, 15th and 16th Kansas, McLain's Battery, the 2nd Colorado, the 3rd Wisconsin and the 1st Brigade were involved., dismounted, totalling less than 2,500.[3] The 11th Kansas ran out of ammunition during the battle, but remained on the field..

One casualty of the first day's fighting was Confederate raider George M. Todd, who had participated in the First Battle of Independence in 1862, where he was guilty of summarily executing two captured Union officers.

Periodic gunfire continued throughout the night, as each side probed the other. Union infantry troops continued their withdrawal to the Big Blue River, west of Independence.

October 22

On the 22nd, Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton's advance force ran into the rear guard of Price's troops (Fagan, with 4500, and Marmaduke with 2500) at the Little Blue River.

At 5 AM, the division moved to the crossing of the Little Blue, where the bridge was found to have been destroyed.[5] A temporary bridge was constructed, and at dawn, Brig. Gen. John McNeil's 2nd brigade, followed by Brig. Gen. John Sanborn's 3rd brigade, of Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton's Union force of 7,000 cavalry[6] crossed the Little Blue River, and engaged Price's rear guard.

Around 2 PM, McNeil's troops began pushing nearer the town. McNeil ordered the 5th Missouri State Militia out as skirmishers, and then dismounted two of his brigades, the 17th Illinois. and 13th Missouri. The Confederates were supported by artillery until about 3 PM.[7]

At about 3 PM, Pleasonton arrived, and recognized that Cabell's Confederate troops were in a difficult situation due to the number of streets entering Independence, providing possible avenues of attack. Sanborn's troops attacked the town from the north and northeast (and thus, from the rear of Price's force),[7] his cavalry on foot. McNeil's troops then attacked from the east, forming about one quarter mile from town,[7] and charging the town on horseback,[8][9] Seven companies of Catherton's 13th Missouri regiment formed into a column of fours, and attacked with sabers,.[5] Other troops in these Brigades included the 7th Kansas, the 17th Illinois, and the 2nd Arkansas cavalry regiments, the 2nd leading the attack by Sanborn's troops. Two of Fagan's Confederate brigades (Arkansans) were roughly handled by the attacking Federals, being pushed back through the city toward the west, where the main Union force lay. The Confederates were supported at this time by Parrott guns. An additional Confederate brigade attempted to stem the onslaught on the grounds of what is now the Community of Christ's Independence Temple, but was practically annihilated by Pleasonton's force with only a few Rebels escaping.

During the battle, the Union captured two rifled cannon,[10] formerly used by the 2nd Missouri Light Artillery (US), 40 dead,[9] also capturing 300 Confederates from Cabell's and Slemon's Brigades.[6][8] Union casualties were 14 killed, 58 wounded and 11 missing, for a total of 83.[11] Confederate officers captured during the attack included officers from the following regiments; 45th Arkansas, the 10th Missouri State Guard, Coffey's, Lowther's, Crabtree's, Freeman's, Gordon's, Slayback's, Elliott's, Jeff Thompson's and Goodwin's.

Marmaduke's division engaged Pleasonton about two miles west of Independence, managing to push the Federals back and hold them until the morning of October 23. The focus of combat then shifted westward from Independence to Westport, in modern Kansas City.

Aftermath

Although Price claimed a victory due to the bravery of Marmaduke and his men, Pleasonton's bold actions greatly worried him. Concerned for the safety of his supplies, Price sent his wagon trains to Little Santa Fe on the Fort Scott Road, once he had crossed the Big Blue River. The following day, the 30,000 troops of both armies joined combat at the Battle of Westport, resulting in a decisive Union victory and the end of major Confederate military efforts in Missouri.

References

- NPS:ABPP

- Chapter 13: The Second Battle of Independence (includes eyewitness report written October 23, 1864) The Centennial History of Independence, Mo. by W.L. Webb, Copyright 1927 by the Author

- Hinton, Richard Josiah (1865). Rebel Invasion of Missouri and Kansas, and the Campaign of the Army of the Border, Against General Sterling Price, in October and November, 1864. Chicago: Church & Goodman. pp. 93–99.

- ibid. Retrieved on 11 July 2008.

- Hinton, Richard Josiah (1865). Rebel Invasion of Missouri and Kansas, and the Campaign of the Army of the Border, Against General Sterling Price, in October and November, 1864. Chicago: Church & Goodman. pp. 114, 116.

- Collins, Charles D. Jr. (2016). "Battlefield Atlas of Price's Missouri Expedition of 1864, p. 90" (PDF). Prices_Missouri_Expedition_web. Combat Studies Institute Press, Fort Leavenworth, Ks 66027. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- Sinisi, Kyle S. (2015). The Last Hurrah: Sterling Price's Missouri Expedition, 1864. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 210.

- Titterington, Dick. "The Civil War Muse". Confederate Line October 22, 1864. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- The War of the Rebellion, a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies.; Series 1 - Volume 41 (Part I). Washington: Government Printing Office. 1893. pp. 313, 336.

- Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Series I - Volume XLI - In Four Parts Part IV-Correspondence, etc. Washington: Government Printing Office. 1893. p. 185.

- Dyer, Frederick H. (1908). A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion. Des Moines, Iowa: The Dyer Publishing Company. p. 813.

External links

- U.S. National Park Service CWSAC Battle Summary

- CWSAC Report Update

- The "First" and "Second" Battles of Independence pp. 708–709, 'Historical Dictionary of the Civil War: A-L' by Terry L. Jones, Rowman & Littlefield, 2002.