Battle of Renfrew

The Battle of Renfrew was fought between the Kingdom of the Isles and the Kingdom of Scotland in 1164, near Renfrew, Scotland. The men of the Isles, accompanied by forces from the Kingdom of Dublin, were commanded by Somairle mac Gilla Brigte, King of the Isles. The identity of the Scottish commander is unrecorded and unknown. Herbert, Bishop of Glasgow, Baldwin, Sheriff of Lanark/Clydesdale, and Walter fitz Alan, Steward of Scotland are all possible candidates for this position. The battle was a disaster for the Islesmen and Dubliners. Somairle was slain in the encounter, apparently by local levies, and his forces were routed.

| Battle of Renfrew | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Kingdom of the Isles Kingdom of Dublin | Kingdom of Scotland | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Somairle mac Gilla Brigte, King of the Isles † | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 160 ships (possibly 6000–8000 men) | local levies? | ||||||

Somairle first appears on record in the 1150s, when he is stated to have supported the cause of Máel Coluim mac Alasdair in a rebellion against Malcolm IV, King of Scotland. Máel Coluim was a member of a rival branch of the Scottish royal family, and his sons were closely related to Somairle. At about the time of the rebellion's collapse, Somairle appears to have shifted his energies from Scotland towards the Isles. In 1156, he wrested about half of the Kingdom of the Isles from his brother-in-law, Guðrøðr Óláfsson, King of the Isles. Two years later, Somairle decisively defeated Guðrøðr, gaining complete control of the kingdom.

The reasons for Somairle's invasion of Scotland are uncertain. One possibility is that he was renewing his support for the sons of Máel Coluim. Another possibility is that he was attempting to conquer the southwest part of Scotland that may have only recently fallen under Scottish royal authority. This region had previously been occupied by the Gall Gaidheil, a people of mixed Scandinavian and Gaelic ethnicity, like Somairle himself. There is reason to suspect that this region was lost to the Scots upon the collapse of Máel Coluim's rebellion, and afterwards doled out to powerful Scottish magnates in the context of Scottish consolidation. Somairle may have also invaded the region in an attempt to counter a perceived threat that the Scots posed to his authority in the Firth of Clyde. The fact that the battle is said to have been fought at Renfrew, the seat of one of Walter's lordships, could indicate that he was a specific target.

As a result of Somairle's death in battle, the Kingdom of the Isles fractured once again. Although Guðrøðr's brother, Rǫgnvaldr, is recorded to have gained power, Guðrøðr was able overcome him within the year. Upon Guðrøðr's reestablishment in the Isles, the realm was again divided between him and Somairle's descendants, in a partitioning that stemmed from Somairle's coup in 1156. The Battle of Renfrew may have been Malcolm's greatest victory. It is certainly the last major event of his reign on record.

Background

At an uncertain point in the mid twelfth century, perhaps in about 1140, Somairle mac Gilla Brigte married Ragnhildr, daughter of Óláfr Guðrøðarson, King of the Isles.[1] This union had severe repercussions on the later history of the Kingdom of the Isles, as it gave Somairle's descendants—Clann Somairle—a claim to the kingship by way of Ragnhildr's royal descent.[2] The year 1153 marked a watershed in the history of the Isles. Not only did David I, King of Scotland die late in May,[3] but the thirteenth- to fourteenth-century Chronicle of Mann reports that Óláfr was assassinated in June, whilst his son, Guðrøðr, was absent in Norway.[4] Within months of his father's assassination, Guðrøðr executed his vengeance. According to the chronicle, he journeyed from Norway to Orkney, enstrengthened by Norwegian military support, and was unanimously acclaimed as king by the leading Islesmen. He is then stated to have continued on to Mann, where he overcame three kin-slaying cousins, and successfully secured the kingship for himself.[5]

In 1155 or 1156, the Chronicle of Mann reveals that Somairle conducted a coup against Guðrøðr, specifying that Somairle's son, Dubgall, was produced as a replacement to Guðrøðr's rule.[6] Late in 1156, on the night of 5/6 January, Somairle and Guðrøðr finally clashed in a bloody but inconclusive sea-battle. According to the chronicle, when the clash finally concluded the feuding brothers-in-law divided the Kingdom of the Isles between themselves.[7] Two years later, the chronicle reveals that Somairle invaded Mann and drove Guðrøðr from the kingship into exile.[8] With Guðrøðr gone, it appears that either Dubgall or Somairle became King of the Isles.[9] Although the young Dubgall may well have been the nominal monarch, the chronicle makes it clear that it was Somairle who possessed the real power.[10] Certainly, Irish sources regard Somairle as a king by the end of his career.[11]

Battle

The Battle of Renfrew is attested by sources such as: the fourteenth-century Annals of Tigernach,[15] the fifteenth- to sixteenth-century Annals of Ulster,[16] the twelfth-century Carmen de Morte Sumerledi,[17] the thirteenth-century Chronica of Roger de Hoveden,[18] the twelfth- to thirteenth-century Chronicle of Holyrood,[19][note 1] the thirteenth- to fourteenth-century Chronicle of Mann,[22] the twelfth- to thirteenth-century Chronicle of Melrose,[23] the thirteenth-century Gesta Annalia I,[24] the fifteenth-century Mac Carthaigh's Book,[25] and the fifteenth-century Scotichronicon.[26]

The Chronicle of Melrose reports that Somairle's forces were drawn "from Ireland and various places".[27] Irish sources—such as the Annals of Tigernach, Annals of Ulster, and Mac Carthaigh's Book—specify that his forces consisted of men from Argyll, Kintyre, the Isles, and Dublin.[28] Such depictions of Somairle's forces appear to reflect the remarkable reach of power that he possessed at his peak.[29] The invasion was clearly a well-planned affair.[30] According to the Chronicle of Mann, Somairle's invasion fleet numbered one hundred and sixty ships.[31][note 2] If each ship carried forty to fifty combatants, Somairle may have led between six thousand and eight thousand men.[34] Although the tallies of combatants given by mediaeval sources are generally suspect, they can be indicative of the magnitude of a force's size.[35][note 3] The participation of Dubliners in Somairle's venture suggests that he had an alliance with the Dubliners.[37] Specifically, he may have had a pact with either the overlord of Dublin, Diarmait Mac Murchada, King of Leinster,[38] or else with Diarmait's own overlord, Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn, High King of Ireland.[39][note 4]

According to the Chronicle of Mann,[50] and the Chronicle of Melrose, Somairle's fleet made landfall at Renfrew.[51] It is possible that the fleet specifically landed at Inchinnan, where his forces could have first engaged the Scots.[52] The battle was evidently a fiasco for the Islesmen,[53] with their commanding-king killed in a skirmish against local levies.[54] The account given by Carmen de Morte Sumerledi certainly suggests that Somairle was killed in the outset—"wounded by spear, slain by the sword"—and overcome by a hastily organised body of local defenders.[55] As such, Somairle could have fallen in the opening encounter, with his leaderless followers giving up the fight.[56][note 5] The account given by Carmen de Morte Sumerledi further states that Somairle's head was cut off by a priest, and presented to Herbert, Bishop of Glasgow.[61] According to Gesta Annalia I, Somairle was killed with a son named Gilla Coluim.[62] It is possible that this source has mistaken the latter's name for Gilla Brigte,[63] the name that the Annals of Tigernach accords to Somairle's slain son.[64][note 6] It is unknown if Dubgall participated in the battle.[67]

The stated location of Renfrew could be evidence that the target of Somairle's strike was Walter fitz Alan, Steward of Scotland.[68] The latter certainly possessed Renfrew during his career, and it is possible that it functioned as the seat of his Strathgryfe group of holdings,[69] or even as the principal seat of his entire lordship.[70] The leadership of the Scottish forces is uncertain.[71] It is conceivable that the commander was one of the three principal men of the region: Herbert,[72] Baldwin, Sheriff of Lanark/Clydesdale,[73] and Walter.[74] Whilst there is reason to suspect that Somairle focused his offensive upon Walter's lordship at Renfrew,[75] it is also possible that Herbert, as Malcolm's agent in the west, was the intended target.[76] Certainly, Carmen de Morte Sumerledi associates Herbert with the victory,[77] and makes no mention of Walter or any Scottish royal forces.[78] On the other hand, Baldwin's nearby lands of Inverkip and Houston were passed by Somairle's naval forces, suggesting that it was either Baldwin or his followers who engaged and overcame the invaders.[71] In any case, the victory over the Islesmen and their allies appears to have ensured peace in Scotland for the rest of Malcolm's rule.[79] It may have been Malcolm's greatest victory,[80] and is certainly the last major event of his reign on record.[81]

Context

.jpg.webp)

Somairle's rise to power appears to coincide with an apparent weakening of Scottish royal authority in Argyll.[82] Such outside influence in Argyll may be evidenced by Scottish royal acta. Specifically, one royal charter, dating to 1141×1147, reveals that David granted a portion of his cáin from Argyll and Kintyre to Holyrood Abbey.[83] Another charter, dating to 1145×1153, shows that the king granted a portion of his cáin from Argyll of Moray, and other revenue from Argyll, to Urquhart Priory.[84][note 7] Several years later, in 1150×1152, David granted another portion of his cáin in Argyll and Kintyre to Dunfermline Abbey.[86] The fact that this charter includes the caveat "in whatever year I should receive it" could indicate that, between 1141 and 1152, the Scottish Crown lost royal control of these territories to Somairle.[87] Although David may well have regarded Argyll as a Scottish tributary, Somairle's ensuing career clearly reveals that the latter regarded himself a fully independent ruler.[88] Somairle's first attestation by a contemporary source occurs in 1153,[89] when the Chronicle of Holyrood reports that he backed the cause of his nepotes, the Meic Máel Coluim, in an unsuccessful coup after David's death.[90] These nepotes—possibly nephews or grandsons of Somairle—were the sons of Máel Coluim mac Alasdair, a claimant to the Scottish throne, descended from an elder brother of David, Alexander I, King of Scotland.[91][note 8] There is reason to suspect that some of the campaigning conducted by Somairle and the Meic Máel Coluim is also evinced by Carmen de Morte Sumerledi, which refers to his wasting of Glasgow, its cathedral, and surrounding countryside.[95][note 9] Upon the collapse of the uprising, Somairle apparently abandoned the Meic Máel Coluim, whereupon he turned his energies towards the Isles.[101] By Christmas 1160, a Scottish royal charter reveals that Somairle had come to an understanding of peace with Malcolm at some point earlier that year.[102][note 10] Nevertheless, four years later Somairle launched his final invasion of Scotland, and it is possible that it was conducted in the context of another attempt to support Máel Coluim's claim to the Scottish throne.[106][note 11]

.png.webp)

.png.webp)

Another possibility is that Somairle was attempting to secure a swathe of territory that had only recently been secured by the Scottish Crown.[106] Although there is no record of Somairle before 1153, his family was evidently involved in an earlier insurrection by Máel Coluim against David that ended with Máel Coluim's capture and imprisonment in 1134.[82][note 13] An aftereffect of this failed insurgency may be perceptible in a Scottish royal charter issued at Cadzow in about 1136.[116] This source records the Scottish Crown's claim to cáin in Carrick, Kyle, Cunningham, and Strathgryfe.[117] Historically, this region appears to have once formed part of the territory dominated by the Gall Gaidheil,[118] a people of mixed Scandinavian and Gaelic ethnicity.[119] One possibility is that these lands had formerly comprised part of a Gall Gaidheil realm before the Scottish Crown overcame Máel Coluim and his supporters.[116] The Cadzow charter is one of several that mark the earliest record of Fergus, Lord of Galloway,[120] a Scandinavian-Gaelic magnate who held lands in Carrick. Fergus' attestation could indicate that, whilst Somairle's family may have suffered marginalisation as a result of Máel Coluim's defeat and David's consolidation of the region, Fergus and his family could have conversely profited at this time as supporters of David's cause.[116] The record of Fergus amongst the Scottish elite at Cadzow is certainly evidence of the increasing reach of David's royal authority in the 1130s.[121]

.jpg.webp)

Another figure first attested by these charters is Walter,[116] a man who may have been granted the lands of Strathgryfe, Renfrew, Mearns, and North Kyle on the occasion of David's grant of cáin.[124] One explanation for Somairle's invasion is that he may have been compelled to counter a threat that Walter[125]—and other recently-enfeoffed Scottish magnates—posed to his authority.[126] A catalyst of this collision of competing spheres of influence may have been the vacuum left by Óláfr's assassination. Although the political uncertainty following Óláfr's elimination would have certainly posed a threat to the Scots, the concurrent build-up of Scottish power along the western seaboard—particularly exemplified by Walter's expansive territorial grants in the region—meant that the Scots were also positioned to capitalise upon the situation.[127] In fact, there is reason to suspect that, during Malcolm's reign—and perhaps with Malcolm's consent—Walter began to extend his own authority into the Firth of Clyde, the islands of the Clyde, the southern shores of Cowal, and the fringes of Argyll.[128][note 14] The allotment of Scottish fiefs along the western seaboard suggests that these lands were settled in the context of defending the Scottish realm from external threats located in Galloway and the Isles.[133] It was probably in this context that substantial western lordships were granted to men such as Hugh de Morville, Robert de Brus, and Walter himself.[134] As such, the mid-part of the twelfth century saw a steady consolidation of Scottish power along the western seaboard by some of the realm's greatest magnates—men who could well have encroached into Somairle's sphere of influence.[135] The continuous encroachment of Scottish authority may well have spurned Somairle to launch a counter-strike.[136] It is conceivable that Somairle first acquired the islands of the Firth of Clyde after his 1156 clash with Guðrøðr. In so doing, Somairle gained control of islands in a territory that appears to have been regarded by the Scots as vital to their own security.[137] In fact, the catalyst for the establishment of Scottish castles along the River Clyde could well have been the potential threat posed by Somairle.[138][note 15]

Somairle's final campaign appears similar to later Norwegian-backed invasions of the Firth of Clyde conducted by his descendants in the thirteenth century (1230 and 1263). In fact, the Viking sack of Alt Clut in 870 may parallel these invasions, since it is possible that Dublin-based Vikings destroyed the fortress of Alt Clut (Dumbarton Castle) in an effort to nullify a threat posed by the Strathclyde Britons.[145][note 16] Another factor that may have spurned Somairle to attack the Scots could have been Malcolm's increasingly poor health.[147] Certainly, the Chronicle of Melrose states that the Scottish king was stricken with a "great sickness" in 1163, and it is possible that he never fully recovered.[148] The fact that the Annals of Ulster accords Malcolm the epithet "Cennmor" ("Big Head") upon his death could be evidence that he suffered from Paget's disease.[149][note 17] One possibility is that the king's impairment was opportunistically seized upon by Somairle, who overestimated a weakening in Scottish royal power.[147]

Aftermath

Although it is conceivable that Dubgall was able to secure power following his father's demise,[147] it is evident from the Chronicle of Mann that the kingship of Mann was soon seized by Guðrøðr's brother, Rǫgnvaldr.[152] Before the end of the year, Guðrøðr is said by the same source to have arrived in the Isles, and ruthlessly overpowered his brother.[153] Guðrøðr thereafter regained the kingship,[154] and the realm was divided between him and Clann Somairle,[155] in a partitioning that stemmed from Somairle's coup in 1156.[156][note 18] Although there is no direct evidence that Somairle's imperium fragmented upon his death, there is reason to suspect that it was indeed divided between his sons.[158] In the decades that followed Somairle's demise, there is evidence to suggest that the known inter-dynastic infighting amongst his descendants was capitalised upon by Walter and his family.[159][note 19]

Queen Blearie's Stone

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

There are several local traditions concerning the location of the battle.[169] One account, dating to the late eighteenth century, asserts that the invaders landed at Renfrew, and that they marched southwards to Knock, an elevated land form situated between Renfrew and Glasgow, where they were defeated by local forces.[170] In 1772, Thomas Pennant visited this site, and observed "a mount or tumulus, with a foss round the base, and a single stone on the top", which he was led to believe marked the spot where Somairle was defeated.[171]

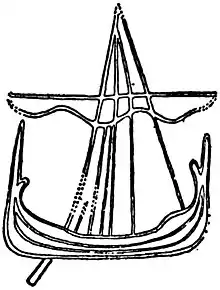

Earlier accounts of the monument accorded it forms of the name "Queen Blearie's Stone", and associated it with accounts linking it to the death of Marjorie Bruce, and the caesarean birth of her son, Robert II, King of Scotland.[172] Pennant's account may have been influenced by David Dalrymple, who suggested that this name may mask a Gaelic toponym—which he gave as Cuiné Blair ("Memorial of Battle")—a name that actually referred to the Battle of Renfrew.[173] If the monument was indeed associated with the battle, it could be identical to the pillar pictured upon Walter's seal. If so, the seal's depiction of a man leaning against a pillar could commemorate the Scottish victory.[174] In any case, "Queen Blearie's Stone" was demolished before the end of the eighteenth century.[175] By this point, part of it evidently formed a lintel of a barn door, although by the mid nineteenth century it disappeared.[176] The approximate site of "Queen Blearie's Stone" (grid reference NS 4932 6614)[177] is now part of a housing estate.[178]

Notes

- This account, and that of Somairle's invasion of Scotland in 1153 given by the same source, are probably the source for the accounts of these events given by Roger's Chronica.[20] The account given by the Chronicle of Melrose may be another source for Roger's account of 1164.[21]

- According to the Chronicle of Mann, Somairle's fleet numbered eighty when he fought Guðrøðr in 1156,[32] and numbered fifty-three when the men clashed again in 1158.[33]

- A near-contemporary account of an attack on Dublin in 1171, given by the twelfth-century Expugnatio Hibernica, describes the participating Islesmen as: "warlike figures, clad in mail in every part of their body after the Danish manner. Some wore long coats of mail, other iron plate skilfully knitted together, and they had round, red shields protected by iron round the edge".[36]

- The following year, Dubliners undertook naval manoeuvres off the coast of Wales, in the service of Henry II, King of England,[40] as evidenced by the Annals of Ulster,[41] and the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century texts Brut y Tywysogyon[42] and Brenhinedd y Saesson.[43] The Dubliners' part in this campaign to subdue the Welsh suggests that Henry also had a deal with Diarmait,[44] or Muirchertach.[45] There is reason to suspect that Somairle and Muirchertach were allied together in 1154, when a certain Mac Scelling is reported to have commanded the mercenary fleet of Muirchertach against forces supporting Toirrdelbach Ua Conchobair, King of Connacht, Muirchertach's then-rival for the Irish highkingship,[46] in an encounter attested by both Annals of the Four Masters,[47] and the Annals of Tigernach.[48] If Somairle and Muirchertach were indeed assisting each other in 1154 and 1164, the latter episode could well have seen Muirchertach return the favour of earlier support.[49]

- Much later Hebridean tradition alleges that Somairle was killed through treachery.[57] Specifically, Clann Domhnaill tradition preserved by the seventeenth-century Sleat History,[58] and the eighteenth-century Book of Clanranald, alleges that Somairle died as a result of a traitorous assassination orchestrated on behalf of the Scottish Crown.[59] One possibility is that such traditions of treachery could have been crafted to explain the sudden demise of a figure imagined by later generations to have been almost invincible in battle.[60]

- Gilla Brigte appears to have been a product of marriage between Somairle and another woman,[65] a union that may have predated Somairle's binding to Ragnhildr.[66]

- Further evidence that the Scots held authority in Argyll may be the fact that men from the Isles and Lorne are stated by the twelfth-century Relatio de Standardo to have formed part of the Scottish forces at the Battle of the Standard in 1138.[85]

- There are several possible ways which Somairle and the Meic Máel Coluim could have been related. On one hand, the sons of Máel Coluim could have been descended from a sister of Somairle.[92] On the other hand, their mother could have been a daughter of Somairle.[93] Another possibility is that Somairle and Máel Coluim were half-brothers, descended from the same mother.[94]

- According to Carmen de Morte Sumerledi, it was the divine intervention of Saint Kentigern,[96] the patron saint of Glasgow,[97] that resulted in the Scots' victory over Somairle in 1164.[96] The apparent attack of 1153, and the negative effects it may have had upon the status of the cathedral's bishop and saint, may account for the original compilation of Carmen de Morte Sumerledi after Somairle's defeat and demise.[98] Although slavery had dwindled in England by the twelfth century, it continued on in Wales, Ireland, and Scotland.[99] At one point, Carmen de Morte Sumerledi states that the attackers of Glasgow "drove out the weak" or "carried off the weak". If the latter interpretation of the phrase is correct, the passage could refer to slaving conducted by the attackers.[100]

- One possibility is that Malcolm swore not to aid Guðrøðr,[103] and that Somairle swore not to aid the cause of Máel Coluim.[104] Somairle may have also acknowledged Malcolm's overlordship of Argyll,[105] or Malcolm may have acknowledged Somairle's right there.[106] The concord between Somairle and Malcolm may have been the occasion in which Somairle earned the epiphet "sit-by-the-king", accorded to him by Carmen de Morte Sumerledi.[107]

- According to the Chronicle of Melrose, Somairle had been attacking the Scots for twelve years before his final invasion.[108] This would give 1152 as the year Somairle began campaigning against the Scots.[109] As such, the given number may be a mistake for eleven years.[71] In any case, the span of time appears to be somewhat generalised on account of the evidence of the concord between Somairle and Malcolm.[110]

- Walter's domain included the depicted regions of Strathgryfe, Renfrew, Mearns, and North Kyle. Clydesdale and South Kyle were royal lordships, whilst Cunningham was a Morville lordship.[112]

- On at least two occasions that may date before 1134, David temporarily based himself at Irvine in Cunningham, a strategic coastal site from where Scottish forces may have conducted seaborne military operations against Malcolm's western allies.[113] The twelfth-century Relatio de Standardo reveals that David received English military assistance against Máel Coluim. This source specifies that a force against Máel Coluim was mustered at Carlisle, and notes successful naval campaigns conducted against David's enemies, which suggests that Máel Coluim's support was indeed centred in Scotland's western coastal periphery.[114] By the mid 1130s, David had not only succeeded in securing Máel Coluim, but also appears to have gained recognition of his overlordship of Argyll.[115]

- The first of Walter's family to hold lordship over Bute may have been his son, Alan.[129] By about 1200,[130] during the latter's career, the family certainly seems to have gained control of the island.[131] By the latter half of the thirteenth century, the family certainly held authority over Cowal.[132]

- Scottish expansion, albeit father afield in Moray, may be perceptible in a vague notice by the Chronicle of Holyrood,[139] stating that Malcolm "moved the men of Moray" in 1163.[140] Although this source may refer to the relocation of the Moravian ecclesiastical see,[141] and not the removal of the native population,[142] it may nevertheless be evidence of Malcolm's extension of royal authority.[143] Whilst there is no known link between the relocation and Somairle's invasion the next year, it is conceivable that there could have been a connection between the events.[144]

- In 1230, Óspakr-Hákon, an apparent descendant of Somairle, led a Norwegian-backed fleet into the Firth of Clyde and captured Rothesay Castle on the island of Bute. The attack upon this stronghold seems to evince the anxiety felt by Somairle's thirteenth-century descendants in the face of the steadily increasing regional influence of Walter's own progeny.[146]

- As such, Malcolm may have been the original "Malcolm Canmore".[150] His eleventh-century predecessor, Malcolm III, King of Scotland was accorded the same epithet in the thirteenth century.[151]

- This division carried on until the demise of the Kingdom of the Isles, in 1265/1266.[157]

- At some an uncertain date, Somairle's son, Ragnall, is known to have made a grant to the Cluniac priory of Paisley.[160] This religious house—which in time became an abbey[161]—was closely associated with Walter's family.[162] Since Ragnall's grant appears to postdate a recorded clash between him and another son of Somairle, Aongus, in 1192, it could be evidence of an attempt by Ragnall—who may have been seriously weakened from his defeat to Aongus—to secure an alliance with Walter's son and successor, Alan fitz Walter, Steward of Scotland.[163] The fact that Bute seems to have fallen into the hands of Walter's family by about 1200 could indicate that Alan capitalised upon Clann Somairle's internal discord and thereby seized the island. Alternately, it is also possible that Alan received the island from Ragnall as payment for military support against Aongus, who seems to have had gained the upper hand over Ragnall by 1192.[164]

- Walter's seal was attached to a charter of his to Melrose Abbey concerning the lands of Mauchline.[166] The device is non-heraldic.[167] Whilst the earliest known seal of his son, Alan, is also non-heraldic, a later one bears the earliest depiction of the heraldic fess chequy borne by the Stewart family.[168]

Citations

- Oram (2011) pp. 88–89; Oram, R (2004) p. 118; McDonald, RA (2000) p. 175 n. 55; McDonald, RA (1997) p. 45; Anderson (1922) p. 255 n. 1.

- Beuermann (2012) p. 5; Beuermann (2010) p. 102; Williams, G (2007) p. 145; Woolf (2005); Brown, M (2004) p. 70; Rixson (2001) p. 85.

- Oram (2011) p. 108.

- Beuermann (2014) p. 85; Downham (2013) p. 171, 171 n. 84; McDonald, RA (2007b) pp. 67, 85, 92; Duffy (2006) p. 65; Beuermann (2002) p. 421; Duffy (2002) p. 48; Sellar (2000) p. 191; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 259; Duffy (1993) pp. 41–42, 42 n. 59; Oram, RD (1988) pp. 80–81; Anderson (1922) p. 225; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 62–65.

- Crawford (2014) p. 74; Downham (2013) p. 171; McDonald, RA (2012) p. 162; Abrams (2007) p. 182; McDonald, RA (2007a) p. 66; McDonald, RA (2007b) pp. 67, 85; Duffy (2006) p. 65; Oram (2000) pp. 69–70; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 259; Gade (1994) p. 199; Oram, RD (1988) p. 81; Anderson (1922) p. 226; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 64–67.

- Holton (2017) p. 125; Wadden (2014) p. 32; Downham (2013) p. 172; Woolf (2013) pp. 3–4; Oram (2011) p. 120; Williams, G (2007) pp. 143, 145–146; Woolf (2007a) p. 80; Barrow (2006) pp. 143–144; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 243–244; Woolf (2004) p. 104; Rixson (2001) p. 85; Oram (2000) pp. 74, 76; McDonald, RA (1997) pp. 52, 54–58; Williams, DGE (1997) pp. 259–260, 260 n. 114; Duffy (1993) pp. 40–41; Duffy (1992) p. 121; McDonald; McLean (1992) pp. 8–9, 12; Scott, JG (1988) p. 40; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196; Anderson (1922) p. 231; Lawrie (1910) p. 20 § 13; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 68–69.

- Caldwell (2016) p. 354; Wadden (2014) p. 32; McDonald, RA (2012) pp. 153, 161; Oram (2011) p. 120; McDonald, RA (2007a) pp. 57, 64; McDonald, RA (2007b) p. 92; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 244; Woolf (2004) p. 104; Oram (2000) pp. 74, 76; McDonald, RA (1997) pp. 52, 56; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 260; McDonald, RA (1995) p. 135; Duffy (1993) p. 43; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 9; Scott, JG (1988) p. 40; Rixson (1982) pp. 86–87; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196; Anderson (1922) pp. 231–232; Lawrie (1910) p. 20 § 13; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 68–69.

- McDonald, RA (2012) pp. 153, 161; Oram (2011) p. 121; McDonald, RA (2007a) pp. 57, 64; McDonald, RA (2007b) pp. 92, 113, 121 n. 86; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 244; Woolf (2004) p. 104; Oram (2000) pp. 74, 76; McDonald, RA (1997) p. 56; Duffy (1993) p. 43; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 9; Rixson (1982) pp. 86–87, 151; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196; Anderson (1922) p. 239; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 68–69.

- McDonald, RA (1997) p. 57.

- Oram (2011) p. 121.

- Holton (2017) p. 124, 124 n. 14; The Annals of Tigernach (2016) § 1164.6; Annals of the Four Masters (2013a) 1083.10; Annals of the Four Masters (2013b) 1083.10; Woolf (2013) p. 3; McDonald, RA (2007b) p. 164; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 1164.6; Sellar (2004); McLeod (2002) p. 31, 31 n. 22; McDonald, RA (2000) p. 179; Sellar (2000) p. 189; McDonald, RA (1997) pp. 57–58; Anderson (1922) p. 254.

- McDonald, RA (2007a) p. 59; McDonald, RA (2007b) pp. 128–129 pl. 1; Rixson (1982) pp. 114–115 pl. 1; Cubbon (1952) p. 70 fig. 24.

- McDonald, RA (2012) p. 151; McDonald, RA (2007a) pp. 58–59; McDonald, RA (2007b) pp. 54–55, 128–129 pl. 1; Wilson (1973) p. 15.

- McDonald, RA (2016) p. 337; McDonald, RA (2012) p. 151; McDonald, RA (2007b) pp. 128–129 pl. 1.

- Holton (2017) p. 125; The Annals of Tigernach (2016) § 1164.6; Wadden (2014) p. 34; Woolf (2013) p. 3; Strickland (2012) p. 107; McDonald, RA (2007b) p. 76; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 1164.6; Woolf (2005); McDonald, RA (2000) p. 169, 169 n. 16, 179; Sellar (2000) p. 189; McDonald, RA (1997) p. 62; Duffy (1999) p. 356; McDonald, RA (1995) p. 135; Duffy (1993) pp. 31, 45; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 197; Anderson (1922) p. 254.

- Jennings (2017) pp. 121, 126; The Annals of Ulster (2017) § 1164.4; Wadden (2014) p. 34; Wadden (2013) p. 208; Strickland (2012) p. 107; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 1164.4; Oram (2011) p. 128; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 245; Pollock (2005) p. 14; Woolf (2005); McDonald, RA (2000) p. 169, 169 n. 16; Oram (2000) p. 76; Duffy (1999) p. 356; Durkan (1998) p. 137; McDonald, RA (1997) p. 67; McDonald, RA (1995) p. 135; Duffy (1993) p. 45; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 197; Anderson (1922) p. 254; Lawrie (1910) p. 80 § 61.

- Neville (2016) p. 7; Cowan (2015) p. 18; Clanchy (2014) p. 169; Woolf (2013); Clancy (2012) p. 19; MacLean (2012) p. 651; Strickland (2012) p. 107; Oram (2011) p. 128; Davies (2009) p. 67; Márkus (2009) p. 113; Broun (2007) p. 164; Clancy (2007) p. 126; Márkus (2007) p. 100; Sellar (2004); Durkan (2003) p. 230; Driscoll (2002) pp. 68–69; McDonald, RA (2002) pp. 103, 111; McDonald, RA (2000) p. 169, 169 n. 16; Durkan (1998) p. 137; McDonald, RA (1997) pp. 41, 61–62; Macquarrie (1996) p. 43; McDonald, RA (1995) p. 135; McDonald; McLean (1992) pp. 3, 3 n. 1, 13; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 197; Brown, JTT (1927) pp. 274–275; Anderson (1922) pp. 256–258; Lawrie (1910) pp. 80–83 § 62; Anderson (1908) p. 243 n. 2; Arnold (1885) pp. 386–388; Skene (1871) pp. 449–451.

- Duffy (1999) p. 356; Duffy (1993) p. 31; Anderson; Anderson (1938) pp. 143–144 n. 6; Anderson (1922) p. 255 n. 1; Anderson (1908) p. 243; Stubbs (1868) p. 224; Riley (1853) p. 262.

- McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 13; Anderson; Anderson (1938) pp. 44, 143–144 n. 6, 190; Anderson (1922) p. 255 n. 1; Bouterwek (1863) pp. 40–41.

- Anderson; Anderson (1938) pp. 44, 143–144 n. 6.

- Anderson (1922) p. 255 n. 1; Anderson (1908) p. 243 n. 1.

- Caldwell (2016) p. 352; Martin, C (2014) p. 193; McDonald, RA (2007a) pp. 57, 64; McDonald, RA (2007b) pp. 54, 121 n. 86; McDonald, RA (2002) p. 117 n. 76; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 150; McDonald, RA (1995) p. 135; Duffy (1993) p. 45; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 13; Barrow (1960) p. 20; Anderson (1922) p. 255 n. 1; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 74–75.

- Woolf (2013) p. 3; Strickland (2012) p. 107; Oram (2011) p. 128; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 245; Pollock (2005) p. 14; Ewart; Pringle; Caldwell et al. (2004) p. 12; McDonald, RA (2000) p. 169, 169 n. 16; Sellar (2000) p. 189; Duffy (1999) p. 356; Duffy (1993) pp. 31, 45; Barrow (1960) p. 20; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 197; Anderson; Anderson (1938) pp. 125 n. 1, 143–144 n. 6; Brown, JTT (1927) p. 275; Anderson (1922) pp. 254–255; Anderson (1908) p. 243 n. 2; Stevenson (1856) p. 130; Stevenson (1835) p. 79.

- Sellar (2000) p. 195 n. 32; Anderson (1922) p. 255 n. 1; Skene (1872) p. 252 ch. 4; Skene (1871) p. 257 ch. 4.

- Mac Carthaigh's Book (2016a) § 1163.2; Mac Carthaigh's Book (2016b) § 1163.2; Duffy (1993) p. 45.

- Pollock (2005) p. 14; Watt (1994) pp. 262–265; Goodall (1759) p. 452 bk. 8 ch. 6.

- Ewart; Pringle; Caldwell et al. (2004) p. 12; Duffy (1993) p. 45; Anderson; Anderson (1938) pp. 143–144 n. 6; Anderson (1922) p. 254; Anderson (1908) p. 243 n. 2; Stevenson (1856) p. 130; Stevenson (1835) p. 79.

- The Annals of Ulster (2017) § 1164.4; Mac Carthaigh's Book (2016a) § 1163.2; Mac Carthaigh's Book (2016b) § 1163.2; The Annals of Tigernach (2016) § 1164.6; Wadden (2014) p. 34; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 1164.4; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 1164.6; McDonald, RA (2000) p. 169 n. 16; Durkan (1998) p. 137; Duffy (1993) pp. 31, 45; Anderson (1922) p. 254; Lawrie (1910) p. 80 § 61.

- Oram (2011) p. 128; Oram (2000) p. 76; McDonald, RA (1997) p. 252.

- Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 245.

- Caldwell (2016) p. 352; Martin, C (2014) p. 193; McDonald, RA (2007a) p. 64; McDonald, RA (2007b) pp. 54, 121 n. 86; McDonald, RA (2002) pp. 109, 117 n. 76; McDonald, RA (1995) p. 135; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 13; Barrow (1960) p. 20; Anderson (1922) p. 255 n. 1; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 74–75.

- McDonald, RA (2007a) p. 64; McDonald, RA (1995) p. 135; Anderson (1922) p. 231; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 68–69.

- McDonald, RA (2007a) p. 64; McDonald, RA (2007b) pp. 54, 121 n. 86; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 9; Rixson (1982) pp. 87, 151; Anderson (1922) p. 239; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 68–69.

- McDonald, RA (2002) p. 109.

- McDonald, RA (2002) pp. 117–118 n. 76.

- McDonald, RA (2007a) pp. 72–73; McDonald, RA (2007b) pp. 121–122; McDonald, RA (2002) pp. 117–118 n. 76; Martin, FX (1994) pp. 132–133; Heath (1989) p. 96; Wright; Forester; Hoare (1905) p. 219 ch. 21; Dimock (1867) p. 264 ch. 21.

- Doherty (2005) p. 353.

- Byrne (2008) p. 23; Duffy (1993) pp. 45–46.

- Wadden (2014) p. 34; Wadden (2013) pp. 208–209; Pollock (2005) p. 14, 14 n. 69; Duffy (1993) pp. 45–46.

- French (2015) p. 232; Downham (2013) p. 173, 173 n. 96; Byrne (2008) p. 23; Martin (2008) p. 62; Duffy (2007) pp. 133, 136–137; Crooks (2005) p. 301; Doherty (2005) p. 353; Flanagan (2005) p. 211; Flanagan (2004); Duffy (1993) pp. 17–18, 46; Duffy (1992) p. 129; Latimer (1989) p. 537, 537 n. 72.

- The Annals of Ulster (2017) § 1165.7; French (2015) p. 232; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 1165.7; Duffy (2007) pp. 133, 136; Duffy (1993) pp. 17–18.

- Downham (2013) p. 173, 173 n. 96; Duffy (2007) pp. 136–137; McDonald, RA (2007a) p. 70; Duffy (1993) pp. 17–18; Duffy (1992) p. 129; Rhŷs; Evans (1890) p. 324; Williams Ab Ithel (1860) pp. 202–203.

- Downham (2013) p. 173, 173 n. 96; Duffy (1993) pp. 17–18; Duffy (1992) p. 129; Latimer (1989) p. 537, 537 n. 72; Jones; Williams; Pughe (1870) p. 679.

- French (2015) p. 232; Byrne (2008) p. 23; Martin (2008) pp. 62–63; Duffy (2007) pp. 136–137; Crooks (2005) p. 301; Flanagan (2005) p. 211; Flanagan (2004); Duffy (1993) p. 46; Duffy (1992) p. 129.

- Martin, FX (1992) pp. 18–19.

- Wadden (2013) p. 208; Pollock (2005) p. 14, 14 n. 69.

- McDonald, RW (2015) pp. 74–75, 74 n. 23; Wadden (2014) pp. 18, 29–30, 30 n. 78; Wadden (2013) p. 208; Annals of the Four Masters (2013a) 1154.11; Annals of the Four Masters (2013b) 1154.11; Clancy (2008) p. 34; Butter (2007) p. 141, 141 n. 121; McDonald, RA (2007a) p. 71; McDonald, RA (2007b) p. 118; Pollock (2005) p. 14; Simms (2000) p. 12; Duffy (1999) p. 356; Ó Corráin (1999) p. 372; Jennings (1994) p. 145; Duffy (1993) p. 31, 31 n. 79; Duffy (1992) pp. 124–125; Sellar (1971) p. 29; Anderson (1922) p. 227.

- Wadden (2014) p. 29; The Annals of Tigernach (2016) § 1154.6; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 1154.6.

- Pollock (2005) p. 14, 14 n. 69.

- McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 13; Anderson (1922) p. 231; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 68–69.

- Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 245; Ewart; Pringle; Caldwell et al. (2004) p. 12; McDonald, RA (2000) p. 169 n. 16; Anderson; Anderson (1938) p. 143 n. 6; Brown, JTT (1927) p. 275; Anderson (1922) p. 254; Anderson (1908) p. 243 n. 2; Stevenson (1856) p. 130; Stevenson (1835) p. 79.

- Woolf (2004) pp. 102, 104; Driscoll (2002) pp. 68, 71.

- Duffy (1993) p. 45.

- Oram (2011) p. 128; Sellar (2004); McDonald, RA (2002) p. 103.

- Sellar (2004); McDonald, RA (2002) p. 103; McDonald, RA (2000) p. 169; Woolf (2013) p. 10; Clancy (2007) p. 126; McDonald, RA (1997) p. 62; Anderson (1922) p. 258; Lawrie (1910) p. 82 § 62; Arnold (1885) p. 388; Skene (1871) p. 450.

- Woolf (2004) p. 105.

- Sellar (2004).

- McDonald, RA (2000) p. 169; McDonald, RA (1997) pp. 61–62; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 13; Macphail (1914) p. 9.

- McDonald, RA (2000) p. 169; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 13; Macbain; Kennedy (1894) pp. 154–155.

- Roberts (1999) p. 96.

- Neville (2016) p. 7; Clanchy (2014) p. 169; Woolf (2013) p. 11; Clancy (2012) p. 19; Clancy (2007) p. 126; Sellar (2004); McDonald, RA (1997) p. 62; Anderson (1922) p. 258; Lawrie (1910) p. 82 § 62; Arnold (1885) p. 388; Skene (1871) p. 450.

- Sellar (2000) p. 195 n. 32; Anderson (1922) p. 255 n. 1; Skene (1872) p. 252 ch. 4; Skene (1871) p. 257 ch. 4; Stevenson (1835) p. 79 n. d.

- Sellar (2004); Sellar (2000) p. 195 n. 32; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 197 n. 6.

- Holton (2017) p. 125; The Annals of Tigernach (2016) § 1164.6; McDonald, RA (2007b) p. 76; Annals of Tigernach (2005) § 1164.6; McDonald, RA (1997) p. 62; Anderson (1922) p. 254.

- Sellar (2004); Sellar (2000) p. 195 n. 32.

- Sellar (2000) p. 195 n. 32.

- McDonald, RA (1997) p. 72.

- Oram (2011) p. 128; Scott, WW (2008); McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 20.

- McDonald, RA (2000) p. 183; Barrow (1973) p. 339; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 20; Barrow (1960) p. 20.

- Young; Stead (2010) p. 26; McDonald, RA (2000) p. 183; McDonald, RA (1997) p. 66; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 16; Barrow (1973) p. 339.

- Barrow (1960) p. 20.

- Oram (2011) p. 128; Woolf (2004) p. 105; Barrow (1960) p. 20.

- Oram (2011) p. 128; Barrow (1960) p. 20.

- Ewart; Pringle; Caldwell et al. (2004) p. 12; Woolf (2004) p. 105; McDonald, RA (2000) p. 184; Roberts (1999) p. 96; Martin, FX (1992) p. 19; McDonald; McLean (1992) pp. 20–21; Barrow (1981) p. 48.

- Oram (2011) p. 128; Hammond (2010) p. 13; Scott, WW (2008); Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 245; McDonald, RA (2000) pp. 183–184; Roberts (1999) p. 96; Barrow (1960) p. 20.

- Pollock (2005) p. 14.

- Woolf (2013) pp. 7–11; Clancy (2012) p. 19; Clancy (2007) p. 126; Sellar (2004); Durkan (2003) p. 230; Durkan (1998) p. 137; Barrow (1981) p. 48; Barrow (1960) p. 20; Brown, JTT (1927) p. 274; Anderson (1922) pp. 256–258; Lawrie (1910) pp. 80–83 § 62; Arnold (1885) pp. 387–388; Skene (1871) pp. 449–451.

- Clanchy (2014) p. 169; Brown, JTT (1927) pp. 274–274.

- Scott, WW (2008).

- Clanchy (2014) p. 169.

- Oram (2011) p. 129.

- Woolf (2004) pp. 102–103.

- MacDonald (2013) p. 37; Oram (2011) p. 88; Woolf (2004) pp. 102–103; Barrow (1999) pp. 124–125 § 147; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 10; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) pp. 195–196; Lawrie (1905) pp. 116–119 § 153, 383–386 § 153; Document 1/4/74 (n.d.).

- MacDonald (2013) p. 37; Barrow (1999) pp. 144–145 § 185; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 10; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) pp. 195–196; Lawrie (1905) pp. 204–205 § 255, 442 § 255; Document 1/4/104 (n.d.).

- Oram (2011) p. 88; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) pp. 195–196; Anderson (1908) p. 200; Howlett (1886) p. 191.

- MacDonald (2013) p. 37; Woolf (2004) pp. 102–103; Barrow (1999) pp. 136–138 § 172; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 10; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) pp. 195–196; Lawrie (1905) pp. 167–171 § 209, 417–419 § 209; Document 1/4/92 (n.d.).

- MacDonald (2013) p. 37; Woolf (2004) pp. 102–103; Barrow (1999) pp. 136–138 § 172; Lawrie (1905) pp. 167–171 § 209, 417–419 § 209; Document 1/4/92 (n.d.).

- Oram (2011) pp. 87–88.

- Woolf (2013) pp. 2–3.

- Wadden (2014) p. 39; Woolf (2013) pp. 2–3; Oram (2011) pp. 72, 111–112; Carpenter (2003) ch. 7 ¶ 46; Ross (2003) pp. 184–185; Anderson; Anderson (1938) pp. 124–125, 187; Anderson (1922) p. 223–224; Bouterwek (1863) p. 36; Stevenson (1856) p. 73.

- Wadden (2013) p. 208; Woolf (2013) p. 3; Oram (2011) pp. 112, 120; Ross (2003) pp. 181–185; Oram (2001).

- Woolf (2013) p. 3; Oram (2011) p. 86; Woolf (2004) p. 102; Ross (2003) pp. 184–185; Oram (2001); Anderson; Anderson (1938) pp. 125 n. 2, 128 n. 3, 129 n. 1.

- Woolf (2013) p. 3.

- Woolf (2013) p. 3, 3 n. 9; Woolf (2004) p. 102.

- Woolf (2013) pp. 6–9; Márkus (2007) p. 100; Anderson (1922) p. 256; Lawrie (1910) p. 81 § 62; Arnold (1885) pp. 386–387; Skene (1871) p. 449.

- Cowan (2015) p. 18; Clanchy (2014) p. 169; Gough-Cooper (2013) pp. 80–81; Woolf (2013) pp. 9–11; Clancy (2012) p. 19; Davies (2009) p. 67; Márkus (2009) p. 113; Clancy (2007) p. 126; Márkus (2007) p. 100; Sellar (2004); Durkan (2003) p. 230; Durkan (1998) p. 137; McDonald, RA (1997) p. 61; Macquarrie (1996) p. 43; Barrow (1981) p. 48; Brown, JTT (1927) p. 274; Anderson (1922) pp. 256–258; Lawrie (1910) pp. 81–83 § 62; Arnold (1885) pp. 387–388; Skene (1871) pp. 449–451.

- Davies (2009) p. 69; Márkus (2007) p. 100; Broun (2004).

- Woolf (2013) pp. 7–8.

- Gillingham (2000) p. 102.

- Woolf (2013) p. 6, 6 n. 21, 9; Anderson (1922) p. 256, 256 n. 3; Lawrie (1910) p. 81 § 62; Arnold (1885) p. 386; Skene (1871) p. 449.

- Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 243–244; Oram, RD (1988) p. 83.

- Neville (2016) p. 11; MacDonald (2013) p. 30 n. 51; Woolf (2013) pp. 4–5; Oram (2011) pp. 114, 119; McDonald, RA (2007b) p. 113; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 245; Sellar (2004); Woolf (2004) p. 104; McDonald, RA (2000) p. 168; McDonald, RA (1997) p. 52; Barrow (1994); McDonald; McLean (1992) pp. 9–10; Barrow (1960) p. 81; Anderson; Anderson (1938) p. 125 n. 1, 136–137 n. 1; Innes (1864) pp. 51–51; Registrum Episcopatus Moraviensis (1837) pp. 453–454 § 1; Document 1/5/52 (n.d.).

- Woolf (2013) pp. 5–6; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 245.

- Woolf (2013) pp. 5–6; Woolf (2004) p. 104.

- Carpenter (2003) ch. 7 ¶ 49.

- Woolf (2004) p. 104.

- MacDonald (2013) p. 30 n. 51; Scott, WW (2008); Roberts (1999) p. 95; McDonald, RA (1997) p. 61; Barrow (1960) p. 15; Woolf (2013) pp. 2, 2 n. 5, 9; Anderson (1922) p. 256, 256 n. 1; Arnold (1885) p. 386; Skene (1871) p. 449, 449 n. 1.

- McDonald, RA (2000) pp. 169 n. 15, 178; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 9; Barrow (1960) p. 20; Anderson; Anderson (1938) pp. 125 n. 1, 143 n. 6; Anderson (1922) p. 254; Anderson (1908) p. 243 n. 2; Stevenson (1856) p. 130; Stevenson (1835) p. 79.

- McDonald, RA (2000) p. 169 n. 15.

- McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 10; Barrow (1960) p. 20.

- Scott, JG (1997) pp. 12–13 fig. 1; Barrow (1975) p. 125 fig. 4.

- Barrow (1975) pp. 125 fig. 4, 131, 131 fig. 6.

- Oram (2011) p. 88; Barrow (1999) pp. 62 § 17, 72–73 § 37; Lawrie (1905) pp. 69 § 84, 70 § 85; 333–334 § 84, 334 § 85; Registrum de Dunfermelyn (1842) pp. 13 § 18, 17 § 31; Document 1/4/2 (n.d.); Document 1/4/15 (n.d.).

- Oram (2011) pp. 71–72, 87; Ross (2003) pp. 182–183; Scott, JG (1997) pp. 25 n. 50, 34; Anderson (1908) pp. 193–194; Howlett (1886) p. 193.

- Oram (2011) pp. 71–72, 87–88.

- Woolf (2004) p. 103.

- Woolf (2004) p. 103; Sharpe (2011) pp. 93–94 n. 236, 94; Barrow (1999) p. 81 § 57; Scott, JG (1997) p. 35; Lawrie (1905) pp. 95–96 § 125, 361–362 § 125; Registrum Episcopatus Glasguensis (1843) p. 12 § 9; Document 1/4/30 (n.d.).

- Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 241; Woolf (2004) pp. 96–97, 99.

- Woolf (2004) pp. 96–97.

- Woolf (2004) p. 103; McDonald, RA (2000) p. 171.

- Oram (2011) p. 89.

- Strickland (2012) p. 113 fig. 3.3; Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) pp. 161 fig. 6c, 184 fig. 11, 189 fig. 16.

- Strickland (2012) p. 113.

- Scott, JG (1997) p. 35.

- Clanchy (2014) p. 169; Oram (2011) p. 128; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 243, 245; Woolf (2004) p. 105; McDonald, RA (1997) pp. 65–66.

- Oram (2011) pp. 127–128; McDonald, RA (1997) pp. 65–66.

- Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 241–243.

- Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 243, 245.

- Barrow (2004b); Barrow; Royan (2004) p. 167; McGrail (1995) pp. 41–42; Barrow (1981) p. 112; Barrow (1980) p. 68.

- Hammond (2010) p. 12; Boardman (2007) pp. 85–86; McAndrew (2006) p. 62; McDonald, RA (1997) pp. 111, 242; McGrail (1995) pp. 41–42; Barrow; Royan (2004) p. 167; Barrow (1981) p. 112; Barrow (1980) p. 68.

- Oram (2011) p. 157; Hammond (2010) p. 12; Boardman (2007) pp. 85–86; McAndrew (2006) p. 62; Barrow (2004b); McDonald, RA (1997) p. 111; McGrail (1995) pp. 41–42; Barrow; Royan (2004) p. 167; Barrow (1981) p. 112; Barrow (1980) p. 68.

- Boardman (2007) p. 86; Barrow; Royan (2004) p. 167; Barrow (1980) p. 68, 68 n. 41.

- McDonald, RA (2000) pp. 181–182; McDonald, RA (1997) p. 65; Barrow (1973) p. 339.

- Carpenter (2003) ch. 6 ¶ 44; McDonald, RA (1997) p. 65.

- Oram (2011) p. 127; McDonald, RA (2000) pp. 182–184; McDonald, RA (1997) pp. 65–66.

- Oram (2011) p. 127; Woolf (2007b) p. 110 n. 42; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 243, 245; Stringer (2005) p. 49; McDonald, RA (2000) pp. 182–184; Roberts (1999) p. 96.

- Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 244.

- Strickland (2012) p. 107.

- Oram (2011) p. 127; McDonald, RA (1999) pp. 167–168.

- Wadden (2013) p. 208; Oram (2011) p. 127; Scott, WW (2008); McDonald, RA (1999) p. 167; McDonald, RA (1997) p. 63; Duncan (1996) p. 191, 191 n. 21; Barrow (1960) p. 19; Anderson (1922) p. 251; Anderson; Anderson (1938) pp. 142, 142–143 n. 2, 190; Bouterwek (1863) p. 40.

- Oram (2011) p. 127; McDonald, RA (1999) p. 168; McDonald, RA (1997) p. 63; Duncan (1996) p. 191; Barrow (1960) p. 19.

- Oram (2011) p. 127; Scott, WW (2008); Duncan (1996) p. 191.

- Oram (2011) p. 127.

- Wadden (2013) p. 208; Scott, WW (2008).

- Woolf (2007b) p. 110 n. 42.

- Oram (2011) p. 192; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 251.

- Oram (2011) p. 128.

- Oram (2011) p. 126; Scott, WW (2008); Anderson (1922) p. 251; Stevenson (1856) p. 129; Stevenson (1835) p. 78.

- The Annals of Ulster (2017) § 1165.8; Oram (2011) p. 126; Scott, WW (2008); The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 1165.8; Barrow (2004a); Anderson (1922) p. 261.

- Scott, WW (2008); Clancy (2002) p. 10 n. 16.

- Scott, WW (2008); Barrow (2004a).

- Oram (2011) pp. 128–129; McDonald, RA (2007b) pp. 67–68, 85; Anderson (1922) pp. 258–259; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 74–75.

- Oram (2011) pp. 128–129; McDonald, RA (2007a) p. 57; McDonald, RA (2007b) pp. 67–68, 85; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 150; Anderson (1922) pp. 258–259; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 74–75.

- McDonald, RA (2007b) p. 85; Duffy (2004).

- Sellar (2004); McDonald, RA (1997) pp. 70–71; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 150.

- McDonald, RA (1997) pp. 70–71; Williams, DGE (1997) pp. 150, 260.

- McDonald, RA (2007b) p. 92.

- Sellar (2000) p. 195; Roberts (1999) p. 97; McDonald, RA (1997) p. 70.

- Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 246–247; Murray (2005) p. 288.

- Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 247; Murray (2005) p. 288; McDonald, RA (2004) pp. 195–196; Oram (2000) p. 111 n. 95; McDonald, RA (1997) pp. 148, 222, 229; McDonald, A (1995) pp. 211–212, 212 n. 132; Registrum Monasterii de Passelet (1832) p. 125; Document 3/30/3 (n.d.).

- Barrow (2004b).

- Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 247; Murray (2005) p. 288.

- Oram (2011) p. 157; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 247; Murray (2005) p. 288; Oram (2000) pp. 106, 111 n. 95.

- Oram (2011) p. 157; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 247.

- McAndrew (2006) p. 62; Birch (1895) p. 266 § 15736; Hewison (1895) pp. 38–39 fig. 1, 46 n. 1; Eyton (1858) p. 225; Laing (1850) p. 126 §§ 769–770, pl. 3 fig. 1; Liber Sancte Marie de Melrose (1837a) p. vii; Liber Sancte Marie de Melrose (1837b) pl. 7 fig. 1.

- Birch (1895) p. 266 § 15736; Hewison (1895) p. 46 n. 1; Eyton (1858) p. 225, 225 n. 66; Laing (1850) p. 126 §§ 769–770; Liber Sancte Marie de Melrose (1837a) pp. 55–56 § 66; Document 3/547/8 (n.d.).

- McAndrew (2006) p. 62; Eyton (1858) p. 225 n. 66; Laing (1850) p. 126 § 770.

- McAndrew (2006) p. 62.

- McDonald, RA (1997) p. 61, 61 n. 66; Metcalfe (1905) pp. 29–30.

- McDonald, RA (1997) p. 61; Metcalfe (1905) pp. 29–30.

- Clark (1998) p. 3; McDonald, RA (1997) p. 61; Metcalfe (1905) pp. 29–30; Groome (1885) p. 243; Pennant (1776) pp. 172–173.

- Steele (2014) p. 145; Clark (1998) pp. 1–2; Gordon (1868) p. 566; Hamilton of Wishaw (1831) pp. 86, 141, 146; Crawfurd; Robertson (1818) p. 148.

- Clark (1998) p. 2; Dalrymple (1797) p. 61 n. †.

- Clark (1998) p. 3.

- Steele (2014) p. 145; Clark (1998) p. 2; Groome (1885) pp. 243–244; Origines Parochiales Scotiae (1851) pp. 77–78; The New Statistical Account of Scotland (1845) p. 14 pt. renfrew.

- Steele (2014) p. 145; The New Statistical Account of Scotland (1845) p. 14 pt. renfrew.

- Knock, Queen Blearie's Stone (n.d.).

- Glasgow Airport Investment Area Scoping Report (2016) p. 70 § 8.3.2.2; Steele (2014) p. 145.

References

Primary sources

- Anderson, AO, ed. (1908). Scottish Annals From English Chroniclers, A.D. 500 to 1286. London: David Nutt. OL 7115802M.

- Anderson, AO, ed. (1922). Early Sources of Scottish History, A.D. 500 to 1286. 2. London: Oliver and Boyd.

- Anderson, MO; Anderson, AO, eds. (1938). A Scottish Chronicle Known as the Chronicle of Holyrood. Publications of the Scottish History Society. Edinburgh: T. and A. Constable.

- "Annals of the Four Masters". Corpus of Electronic Texts (3 December 2013 ed.). University College Cork. 2013a. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- "Annals of the Four Masters". Corpus of Electronic Texts (16 December 2013 ed.). University College Cork. 2013b. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- "Annals of Tigernach". Corpus of Electronic Texts (13 April 2005 ed.). University College Cork. 2005. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- Arnold, T, ed. (1885). Symeonis Monachi Opera Omnia. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. 2. London: Longmans & Co.

- Barrow, GWS, ed. (1999). The Charters of David I: The Written Acts of David I King of Scots, 1124–53, and of his Son Henry, Earl of Northumberland, 1139–52. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-731-9.

- Bouterwek, CW, ed. (1863). Monachi Anonymi Scoti Chronicon Anglo-Scoticum. Elberfeld: Sam. Lucas. hdl:2027/hvd.hx15nb.

- Crawfurd, G; Robertson, G (1818). A General Description of the Shire of Renfrew. Paisley: H. Crichton.

- Dalrymple, D (1797). Annals of Scotland, From the Accession of Malcolm III to the Accession of the House of Stewart. 3. London: William Creech. OL 20478027M.

- Dimock, JF, ed. (1867). Giraldi Cambrensis Opera. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. 5. London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer.

- "Document 1/4/2". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- "Document 1/4/15". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- "Document 1/4/30". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- "Document 1/4/74". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- "Document 1/4/92". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- "Document 1/4/104". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- "Document 1/5/52". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- "Document 3/30/3". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- "Document 3/547/8". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- Goodall, W, ed. (1759). Joannis de Fordun Scotichronicon cum Supplementis ac Continuatione Walteri Boweri. 1. Edinburgh: Roberti Flaminii. hdl:2027/mdp.39015005759389.

- Gordon, JFS (1868). Monasticon. 1. Glasgow: John Tweed. OL 7239194M.

- Groome, FH, ed. (1885). Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland: A Survey of Scottish Topography, Statistical, Biographical, and Historical. 6. Edinbugh: Thomas C. Jack.

- Hamilton of Wishaw, W (1831), Descriptions of the Sheriffdoms of Lanark and Renfrew, Glasgow: Maitland Club, OL 24829880M

- Howlett, R, ed. (1886). Chronicles of the Reigns of Stephen, Henry II, and Richard I. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. 3. London: Longman & Co.

- Innes, C, ed. (1864). Ane Account of the Familie of Innes, Compiled by Duncan Forbes of Culloden, 1608. Aberdeen: The Spalding Club. OL 24829824M.

- Jones, O; Williams, E; Pughe, WO, eds. (1870). The Myvyrian Archaiology of Wales. Denbigh: Thomas Gee. OL 6930827M.

- Lawrie, AC, ed. (1905). Early Scottish Charters, prior to A.D. 1153. Glasgow: James MacLehose and Sons. OL 7024304M.

- Lawrie, AC, ed. (1910). Annals of the Reigns of Malcolm and William, Kings of Scotland, A.D. 1153–1214. James MacLehose and Sons. OL 7217114M.

- Macbain, A; Kennedy, J, eds. (1894). Reliquiæ Celticæ: Texts, Papers and Studies in Gaelic Literature and Philology, Left by the Late Rev. Alexander Cameron, LL.D. 2. Inverness: The Northern Counties Newspaper and Printing and Publishing Company. OL 24821349M.

- "Mac Carthaigh's Book". Corpus of Electronic Texts (21 June 2016 ed.). University College Cork. 2016a. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- "Mac Carthaigh's Book". Corpus of Electronic Texts (21 June 2016 ed.). University College Cork. 2016b. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- Macphail, JRN, ed. (1914). Highland Papers. Publications of the Scottish History Society. 1. Edinburgh: Scottish History Society. OL 23303390M.

- Metcalfe, WM (1905). A History of the County of Renfrew From the Earliest Times. Paisley: Alexander Gardner. OL 17981923M.

- Munch, PA; Goss, A, eds. (1874). Chronica Regvm Manniæ et Insvlarvm: The Chronicle of Man and the Sudreys. 1. Douglas, IM: Manx Society.

- Origines Parochiales Scotiae: The Antiquities, Ecclesiastical and Territorial, of the Parishes of Scotland. 1. Edinburgh: W.H. Lizars. 1851. OL 24829751M.

- Pennant, T (1776). A Tour in Scotland and Voyage to the Hebrides, MDCCLXXII. 1 (2nd ed.). London: Benj. White.

- Registrum de Dunfermelyn. Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club. 1842. OL 24829743M.

- Registrum Episcopatus Glasguensis. 1. Edinburgh. 1843. OL 14037534M.

- Registrum Episcopatus Moraviensis. Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club. 1837. OL 23368344M.

- Registrum Monasterii de Passelet, Cartas Privilegia Conventiones Aliaque Munimenta Complectens, A Domo Fundata A.D. MCLXIII Usque Ad A.D. MDXXIX. Edinburgh. 1832. OL 24829867M.

- Rhŷs, J; Evans, JG, eds. (1890). The Text of the Bruts From the Red Book of Hergest. Oxford. OL 19845420M.

- Riley, HT, ed. (1853). The Annals of Roger de Hoveden: Comprising the History of England and of Other Countries of Europe, From A.D. 732 to A.D. 1201. 1. London: H. G. Bohn. OL 7095424M.

- Skene, WF, ed. (1871). Johannis de Fordun Chronica Gentis Scotorum. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. OL 24871486M.

- Skene, WF, ed. (1872). John of Fordun's Chronicle of the Scottish Nation. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. OL 24871442M.

- Stevenson, J, ed. (1835). Chronica de Mailros. Edinburgh: The Bannatyne Club. OL 13999983M.

- Stevenson, J, ed. (1856). The Church Historians of England. 4. London: Seeleys.

- Stubbs, W, ed. (1868). Chronica Magistri Rogeri de Houedene. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. 1. Longmans, Green, and Co. OL 16619297M.

- "The Annals of Tigernach". Corpus of Electronic Texts (8 February 2016 ed.). University College Cork. 2016. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- "The Annals of Ulster". Corpus of Electronic Texts (29 August 2008 ed.). University College Cork. 2008. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- "The Annals of Ulster". Corpus of Electronic Texts (6 January 2017 ed.). University College Cork. 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- The New Statistical Account of Scotland. 7. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons. 1845.

- Watt, DER, ed. (1994). Scotichronicon. 4. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press. ISBN 1-873644-353.

- Williams Ab Ithel, J, ed. (1860). Brut y Tywysigion; or, The Chronicle of the Princes. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts. OL 24776516M.

- Wright, T; Forester, T; Hoare, RC, eds. (1905). The Historical Works of Giraldus Cambrensis. London: George Bell & Sons.

Secondary sources

- Abrams, L (2007). "Conversion and the Church in the Hebrides in the Viking Age". In Smith, BB; Taylor, S; Williams, G (eds.). West Over Sea: Studies in Scandinavian Sea-Borne Expansion and Settlement Before 1300. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp. 169–193. ISBN 978-90-04-15893-1. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Barrow, GWS, ed. (1960). The Acts of Malcolm IV, King of Scots, 1153–1165. Regesta Regum Scottorum, 1153–1424. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Barrow, GWS (1973). The Kingdom of the Scots: Government, Church and Society From the Eleventh to the Fourteenth Century. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Barrow, GWS (1975). "The Pattern of Lordship and Feudal Settlement in Cumbria". Journal of Medieval History. 1 (2): 117–138. doi:10.1016/0304-4181(75)90019-6. eISSN 1873-1279. ISSN 0304-4181.

- Barrow, GWS (1980). The Anglo-Norman Era in Scottish History. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-822473-7.

- Barrow, GWS (1981). Kingship and Unity: Scotland 1000–1306. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-6448-5.

- Barrow, GWS (1994). "The Date of the Peace between Malcolm IV and Somerled of Argyll". Scottish Historical Review. 73 (2): 222–223. doi:10.3366/shr.1994.73.2.222. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241.

- Barrow, GWS (2004a). "Malcolm III (d. 1093)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17859. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- Barrow, GWS (2004b). "Stewart Family (per. c.1110–c.1350)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49411. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Barrow, GWS (2006). "Skye From Somerled to A.D. 1500" (PDF). In Kruse, A; Ross, A (eds.). Barra and Skye: Two Hebridean Perspectives. Edinburgh: The Scottish Society for Northern Studies. pp. 140–154. ISBN 0-9535226-3-6.

- Barrow, GWS; Royan, A (2004) [1985]. "James Fifth Stewart of Scotland, 1260(?)–1309". In Stringer, KJ (ed.). Essays on the Nobility of Medieval Scotland. Edinburgh: John Donald. pp. 166–194. ISBN 1-904607-45-4 – via Questia.

- Beuermann, I (2002). "Metropolitan Ambitions and Politics: Kells-Mellifont and Man & the Isles". Peritia. 16: 419–434. doi:10.1484/J.Peri.3.497. eISSN 2034-6506. ISSN 0332-1592.

- Beuermann, I (2010). "'Norgesveldet?' South of Cape Wrath? Political Views Facts, and Questions". In Imsen, S (ed.). The Norwegian Domination and the Norse World c. 1100–c. 1400. Trondheim Studies in History. Trondheim: Tapir Academic Press. pp. 99–123. ISBN 978-82-519-2563-1.

- Beuermann, I (2014). "No Soil for Saints: Why was There No Native Royal Martyr in Man and the Isles". In Sigurðsson, JV; Bolton, T (eds.). Celtic-Norse Relationships in the Irish Sea in the Middle Ages, 800–1200. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp. 81–95. ISBN 978-90-04-25512-8. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Beuermann, I (2012). The Norwegian Attack on Iona in 1209–10: The Last Viking Raid?. Iona Research Conference, April 10th to 12th 2012. pp. 1–10. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- Birch, WDG (1895). Catalogue of Seals in the Department of Manuscripts in the British Museum. 4. London: Longmans and Co.

- Boardman, S (2007). "The Gaelic World and the Early Stewart Court" (PDF). In Broun, D; MacGregor, M (eds.). Mìorun Mòr nan Gall, 'The Great Ill-Will of the Lowlander'? Lowland Perceptions of the Highlands, Medieval and Modern. Centre for Scottish and Celtic Studies, University of Glasgow. pp. 83–109. OCLC 540108870.

- Broun, D (2004). "Kentigern (d. 612x14)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15426. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- Broun, D (2007). Scottish Independence and the Idea of Britain: From the Picts to Alexander III. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-2360-0.

- Brown, JTT (1927). "The Origin of the House of Stewart". Scottish Historical Review. 24 (3): 265–279. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241. JSTOR 25525737.

- Brown, M (2004). The Wars of Scotland, 1214–1371. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1237-8.

- Butter, R (2007). Cill- Names and Saints in Argyll: A Way Towards Understanding the Early Church in Dál Riata? (PhD thesis). 1. University of Glasgow.

- Byrne, FJ (2008) [1987]. "The Trembling Sod: Ireland in 1169". In Cosgrove, A (ed.). Medieval Ireland, 1169–1534. New History of Ireland. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–42. ISBN 978-0-19-821755-8.

- Caldwell, DH (2016). "The Sea Power of the Western Isles of Scotland in the Late Medieval Period". In Barrett, JH; Gibbon, SJ (eds.). Maritime Societies of the Viking and Medieval World. The Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph. Milton Park, Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 350–368. doi:10.4324/9781315630755. ISBN 978-1-315-63075-5. ISSN 0583-9106.

- Caldwell, DH; Hall, MA; Wilkinson, CM (2009). "The Lewis Hoard of Gaming Pieces: A Re-examination of Their Context, Meanings, Discovery and Manufacture". Medieval Archaeology. 53 (1): 155–203. doi:10.1179/007660909X12457506806243. eISSN 1745-817X. ISSN 0076-6097.

- Carpenter, D (2003). The Struggle For Mastery: Britain 1066–1284 (EPUB). The Penguin History of Britain. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-14-193514-0.

- Clanchy, MT (2014) [1983]. England and its Rulers, 1066–1307. Wiley Blackwell Classic Histories of England (4th ed.). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-73623-4.

- Clancy, TO (2002). "'Celtic' or 'Catholic'? Writing the History of Scottish Christianity, AD 664–1093". Records of the Scottish Church History Society. 32: 5–39.

- Clancy, TO (2007). "A Fragmentary Literature: Narrative and Lyric from the Early Middle Ages". In Clancy, TO; Pittock, M; Brown, I; Manning, S; Horvat, K; Hales, A (eds.). The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature. 1. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 123–131. ISBN 978-0-7486-1615-2.

- Clancy, TO (2008). "The Gall-Ghàidheil and Galloway" (PDF). The Journal of Scottish Name Studies. 2: 19–51. ISSN 2054-9385.

- Clancy, TO (2012). "Scottish Literature Before Scottish Literature". In Carruthers, G; McIlvanney, L (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Scottish Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–26. doi:10.1017/CCO9781139045407.003. ISBN 9781139045407.

- Clark, S (1998). "Queen Blearie: The Vicissitudes of a Legend" (PDF). Renfrewshire Local History Forum Journal. 9.

- Cowan, M (2015). "'The Saints of the Scottish Country will Fight Today': Robert the Bruce's Alliance With the Saints at Bannockburn". International Review of Scottish Studies. 40: 1–32. doi:10.21083/irss.v40i0.3108. ISSN 1923-5763.

- Crawford, BE (2014). "The Kingdom of Man and the Earldom of Orkney—Some Comparisons". In Sigurðsson, JV; Bolton, T (eds.). Celtic-Norse Relationships in the Irish Sea in the Middle Ages, 800–1200. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp. 65–80. ISBN 978-90-04-25512-8. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Crooks, P (2005). "Mac Murchada, Diarmait". In Duffy, S (ed.). Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 299–302. ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- Cubbon, W (1952). Island Heritage: Dealing With Some Phases of Manx History. Manchester: George Falkner & Sons. OL 24831804M.

- Davies, JR (2009). "Bishop Kentigern Among the Britons". In Boardman, S; Davies, JR; Williamson, E (eds.). Saints' Cults in the Celtic World. Studies in Celtic History. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 66–90. ISBN 978-1-84383-432-8. ISSN 0261-9865.

- Doherty, C (2005). "Naval Warfare". In Duffy, S (ed.). Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 352–353. ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- Downham, C (2013). "Living on the Edge: Scandinavian Dublin in the Twelfth Century". No Horns on Their Helmets? Essays on the Insular Viking-Age. Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and Scandinavian Studies. Aberdeen: Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies and The Centre for Celtic Studies, University of Aberdeen. pp. 157–178. ISBN 978-0-9557720-1-6. ISSN 2051-6509.

- Driscoll, ST (2002). Alba: The Gaelic Kingdom of Scotland, AD 800 – 1124. The Making of Scotland. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-145-3. OL 3646049M.

- Duffy, S (1992). "Irishmen and Islesmen in the Kingdoms of Dublin and Man, 1052–1171". Ériu. 43: 93–133. eISSN 2009-0056. ISSN 0332-0758. JSTOR 30007421.

- Duffy, S (1993). Ireland and the Irish Sea Region, 1014–1318 (PhD thesis). Trinity College, Dublin. hdl:2262/77137.

- Duffy, S (1999). "Ireland and Scotland, 1014–1169: Contacts and Caveats". In Smyth, AP (ed.). Seanchas: Studies in Early and Medieval Irish Archaeology, History and Literature in Honour of Francis J. Byrne. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 348–356. ISBN 1-85182-489-8.

- Duffy, S (2002). "The Bruce Brothers and the Irish Sea World, 1306–29". In Duffy, S (ed.). Robert the Bruce's Irish Wars: The Invasions of Ireland 1306–1329. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. pp. 45–70. ISBN 0-7524-1974-9.

- Duffy, S (2004). "Godred Crovan (d. 1095)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/50613. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Duffy, S (2006). "The Royal Dynasties of Dublin and the Isles in the Eleventh Century". In Duffy, S (ed.). Medieval Dublin. 7. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 51–65. ISBN 1-85182-974-1.

- Duffy, S (2007). "Henry II and England's Insular Neighbours". In Harper-Bill, C; Vincent, N (eds.). Henry II: New Interpretations. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 129–153. ISBN 978-1-84383-340-6.

- Duncan, AAM (1996) [1975]. Scotland: The Making of the Kingdom. The Edinburgh History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Mercat Press. ISBN 0-901824-83-6.

- Duncan, AAM; Brown, AL (1956–1957). "Argyll and the Isles in the Earlier Middle Ages" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 90: 192–220. eISSN 2056-743X. ISSN 0081-1564.

- Durkan, J (1998). "Cadder and Environs, and the Development of the Church in Glasgow in the Twelfth Century". The Innes Review. 49 (2): 127–142. doi:10.3366/inr.1998.49.2.127. eISSN 1745-5219. ISSN 0020-157X.

- Durkan, J (2003). "Cowal Part of Strathclyde in the Early Twelfth Century". The Innes Review. 54 (2): 230–233. doi:10.3366/inr.2003.54.2.230. eISSN 1745-5219. ISSN 0020-157X.

- Ewart, G; Pringle, D; Caldwell, D; Campbell, E; Driscoll, S; Forsyth, K; Gallagher, D; Holden, T; Hunter, F; Sanderson, D; Thoms, J (2004). "Dundonald Castle Excavations, 1986–93". Scottish Archaeological Journal. 26 (1–2): i–x, 1–166. eISSN 1766-2028. ISSN 1471-5767. JSTOR 27917525.

- Eyton, RW (1858). Antiquities of Shropshire. 7. London: John Russell Smith.

- Flanagan, MT (2004). "Mac Murchada, Diarmait (c.1110–1171)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17697. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Flanagan, MT (2005). "Henry II". In Duffy, S (ed.). Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 210–212. ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- Forte, A; Oram, RD; Pedersen, F (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2.

- French, NE (2015). "Dublin, 1160–1200: Part 2". Dublin Historical Record. 68 (2): 227–242. ISSN 0012-6861. JSTOR 24616096.

- Gade, KE (1994). "1236: Órækja Meiddr ok Heill Gerr" (PDF). In Tómasson, S (ed.). Samtíðarsögur: The Contemporary Sagas. Forprent. Reykjavík: Stofnun Árna Magnússona. pp. 194–207.

- Gillingham, J (2000). The English in the Twelfth Century: Imperialism, National Identity, and Political Values. The Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-732-7.

- Glasgow Airport Investment Area Scoping Report (PDF) (v1.2 ed.). Edinburgh: Sweco. 2016.

- Gough-Cooper, HW (2013). "Review of A Ritchie, Historic Bute: Land and People". The Innes Review. 64 (1): 78–82. doi:10.3366/inr.2013.0051. eISSN 1745-5219. ISSN 0020-157X.

- Hammond, M (2010). The First Hundred Years of Paisley Abbey's Patrons: The Stewart Family and Their Tenants to 1241. Scotland's Cluniac Heritage: The Abbeys of Paisley and Crossraguel.

- Heath, I (1989). Armies of Feudal Europe, 1066–1300 (2nd ed.). Wargames Research Group.

- Hewison, JK (1895). The Isle of Bute in the Olden Time. 2. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons.

- Holton, CT (2017). Masculine Identity in Medieval Scotland: Gender, Ethnicity, and Regionality (PhD thesis). University of Guelph. hdl:10214/10473.

- Jennings, A (1994). Historical Study of the Gael and Norse in Western Scotland From c.795 to c.1000 (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh. hdl:1842/15749.

- Jennings, A (2017). "Three Scottish Coastal Names of Note: Earra-Ghàidheal, Satíriseið, and Skotlandsfirðir". In Worthington, D (ed.). The New Coastal History: Cultural and Environmental Perspectives From Scotland and Beyond. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 119–129. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-64090-7_7. ISBN 978-3-319-64090-7.

- "Knock, Queen Blearie's Stone". Canmore. n.d. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- Laing, H (1850). Descriptive Catalogue of Impressions From Ancient Scottish Seals, Royal, Baronial, Ecclesiastical, and Municipal, Embracing a Period From A.D. 1094 to the Commonwealth. Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club. OL 24829707M.

- Latimer, P (1989). "Henry II's Campaign against the Welsh in 1165". The Welsh History Review. 14 (4): 523–552. eISSN 0083-792X. hdl:10107/1080171. ISSN 0043-2431.

- Liber Sancte Marie de Melrose: Munimenta Vetustiora Monasterii Cisterciensis de Melros. 1. Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club. 1837a. OL 24829686M.

- Liber Sancte Marie de Melrose: Munimenta Vetustiora Monasterii Cisterciensis de Melros. 2. Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club. 1837b. OL 24829797M.

- Lynch, M (1991). Scotland: A New History. London: Century. ISBN 0-7126-3413-4.

- MacDonald, IG (2013). Clerics and Clansmen: The Diocese of Argyll between the Twelfth and Sixteenth Centuries. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-18547-0. ISSN 1569-1462.

- MacLean, S (2012). "Recycling the Franks in Twelfth-Century England: Regino of Prüm, the Monks of Durham, and the Alexandrine Schism" (PDF). Speculum. 87 (3): 649–681. doi:10.1017/S0038713412003053. eISSN 2040-8072. hdl:10023/4175. ISSN 0038-7134. JSTOR 23488494.

- Macquarrie, A (1996). "Lives of Scottish Saints in the Aberdeen Breviary: Some Problems of Sources for Strathclyde Saints". Records of the Scottish Church History Society. 26: 31–54.

- Márkus, G (2007). "Saving Verse: Early Medieval Religious Poetry". In Clancy, TO; Pittock, M; Brown, I; Manning, S; Horvat, K; Hales, A (eds.). The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature. 1. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 91–102. ISBN 978-0-7486-1615-2.

- Márkus, G (2009). "Dewars and Relics in Scotland: Some Clarifications and Questions". The Innes Review. 60 (2): 95–144. doi:10.3366/E0020157X09000493. eISSN 1745-5219. ISSN 0020-157X.

- Martin, C (2014). "A Maritime Dominion — Sea-Power and the Lordship". In Oram, RD (ed.). The Lordship of the Isles. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp. 176–199. doi:10.1163/9789004280359_009. ISBN 978-90-04-28035-9. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Martin, FX (1992). "Ireland in the Time of St. Bernard, St. Malachy, St. Laurence O'Toole". Seanchas Ardmhacha: Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society. 15 (1): 1–35. doi:10.2307/29742533. ISSN 0488-0196. JSTOR 29742533.

- Martin, FX (1994) [1967]. "The Normans: Arrival and Settlement (1169–c. 1300)". In Moody, TW; Martin, FX (eds.). The Course of Irish History (1994 revised and enhanced ed.). Cork: Mercier Press. pp. 123–143. ISBN 1-85635-108-4.

- Martin, FX (2008) [1987]. "Diarmait Mac Murchada and the Coming of the Anglo-Normans". In Cosgrove, A (ed.). Medieval Ireland, 1169–1534. New History of Ireland. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 43–66. ISBN 978-0-19-821755-8.

- McAndrew, BA (2006). Scotland's Historic Heraldry. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843832614.

- McDonald, A (1995). "Scoto-Norse Kings and the Reformed Religious Orders: Patterns of Monastic Patronage in Twelfth-Century Galloway and Argyll". Albion. 27 (2): 187–219. doi:10.2307/4051525. ISSN 0095-1390. JSTOR 4051525.

- McDonald, RA (1995). "Images of Hebridean Lordship in the Late Twelfth and Early Thirteenth Centuries: The Seal of Raonall Mac Sorley". Scottish Historical Review. 74 (2): 129–143. doi:10.3366/shr.1995.74.2.129. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241. JSTOR 25530679.

- McDonald, RA (1997). The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's Western Seaboard, c. 1100–c. 1336. Scottish Historical Monographs. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. ISBN 978-1-898410-85-0.

- McDonald, RA (1999). "'Treachery in the Remotest Territories of Scotland': Northern Resistance to the Canmore Dynasty, 1130–1230". Canadian Journal of History. 34 (2): 161–192. doi:10.3138/cjh.34.2.161. eISSN 2292-8502. ISSN 0008-4107.

- McDonald, RA (2000). "Rebels Without a Cause? The Relations of Fergus of Galloway and Somerled of Argyll With the Scottish Kings, 1153–1164". In Cowan, E; McDonald, R (eds.). Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. pp. 166–186. ISBN 1-86232-151-5.

- McDonald, RA (2002). "Soldiers Most Unfortunate". In McDonald, R (ed.). History, Literature, and Music in Scotland, 700–1560. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 93–119. ISBN 0-8020-3601-5.

- McDonald, RA (2004). "Coming in From the Margins: The Descendants of Somerled and Cultural Accommodation in the Hebrides, 1164–1317". In Smith, B (ed.). Britain and Ireland, 900–1300: Insular Responses to Medieval European Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 179–198. ISBN 0-511-03855-0.

- McDonald, RA (2007a). "Dealing Death From Man: Manx Sea Power in and around the Irish Sea, 1079–1265". In Duffy, S (ed.). The World of the Galloglass: Kings, Warlords and Warriors in Ireland and Scotland, 1200–1600. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 45–76. ISBN 978-1-85182-946-0.

- McDonald, RA (2007b). Manx Kingship in its Irish Sea Setting, 1187–1229: King Rǫgnvaldr and the Crovan Dynasty. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-84682-047-2.

- McDonald, RA (2012). "The Manx Sea Kings and the Western Oceans: The Late Norse Isle of Man in its North Atlantic Context, 1079–1265". In Hudson, B (ed.). Studies in the Medieval Atlantic. The New Middle Ages. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 143–184. doi:10.1057/9781137062390.0012. ISBN 978-1-137-06239-0.

- McDonald, RA (2016). "Sea Kings, Maritime Kingdoms and the Tides of Change: Man and the Isles and Medieval European Change, AD c1100–1265". In Barrett, JH; Gibbon, SJ (eds.). Maritime Societies of the Viking and Medieval World. The Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph. Milton Park, Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 333–349. doi:10.4324/9781315630755. ISBN 978-1-315-63075-5. ISSN 0583-9106.

- McDonald, RA; McLean, SA (1992). "Somerled of Argyll: A New Look at Old Problems". Scottish Historical Review. 71 (1–2): 3–22. eISSN 1750-0222. ISSN 0036-9241. JSTOR 25530531.

- McDonald, RW (2015). "Outsiders, Vikings, and Merchants: The Context Dependency of the Gall-Ghàidheil in Medieval Ireland and Scotland". Journal of the Australian Early Medieval Association. 11: 67–86. ISSN 1449-9320.

- McGrail, MJ (1995). The Language of Authority: The Expression of Status in the Scottish Medieval Castle (MA thesis). McGill University.

- McLeod, W (2002). "Rí Innsi Gall, Rí Fionnghall, Ceannas nan Gàidheal: Sovereignty and Rhetoric in the Late Medieval Hebrides". Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies. 43: 25–48. ISSN 1353-0089.