Battle of Sakarya

The Battle of Sakarya (Turkish: Sakarya Meydan Muharebesi, lit. 'Sakarya Field Battle'), also known as the Battle of the Sangarios (Greek: Μάχη του Σαγγαρίου, romanized: Máchi tou Sangaríou), was an important engagement in the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922), the western front of the Turkish War of Independence.

| Battle of Sakarya | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Greco-Turkish War (1919–22) of the Turkish War of Independence | |||||||

At Duatepe observation hill (in Polatlı): Fevzi Çakmak, Kâzım Özalp, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, İsmet İnönü and Hayrullah Fişek | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

96,326 soldiers 5,401 officers 54,572 rifles 825 machine guns 196 cannons 1,309 swords 2 aircraft [4] |

120,000 soldiers 3,780 officers 57,000 rifles 2,768 machine guns 386 cannons 1,350 swords 600 3-ton trucks 240 1-ton trucks 18 airplanes[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

3,700 dead 18,480 wounded 108 captives 5,639 deserters 8,089 missing Total: 38,029[5][Note 1] |

From August 23 to September 16:[7] 4,000 dead 19,000 wounded 354 missing Total: 22,900 | ||||||

The battle went on for 21 days from August 23 to September 13, 1921, close to the banks of the Sakarya River in the immediate vicinity of Polatlı, which is today a district of the Ankara Province.[8] The battle line stretched over 62 miles (100 km).[9]

It is also known as the Officers' Battle[10] (Turkish: Subaylar Savaşı) in Turkey because of the unusually high casualty rate (70–80%) among the officers.[11] Later, it was also called "Melhâme-i Kübrâ" (Islamic equivalent to Armageddon) by Kemal Atatürk.[12]

The Battle of Sakarya is considered as the turning point of the Turkish War of Independence.[13][14][15][16][17][18][19] A Turkish observer, writer and literary critic İsmail Habip Sevük, later described the importance of the battle with the words, "The retreat that started in Vienna on 13 September 1683 stopped 238 years later".[20]

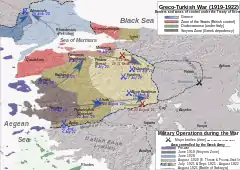

Operational theater

The Greek offensive under King Constantine as Supreme Commander of the Greek Forces in Asia was committed on July 16, 1921, and was skilfully executed. A feint towards the Turkish right flank at Eskişehir distracted Ismet Pasha just as the major assault fell on the left at Kara Hisar. The Greeks then wheeled their axis to the north and swept towards Eskişehir, rolling up the Turkish defence in a series of frontal assaults combined with flanking movements.[21]

Eskişehir fell on July 17, despite a vigorous counter-attack by Ismet Pasha who was determined to fight to the finish. The saner counsels of Mustafa Kemal prevailed, however, and Ismet disengaged with great losses to reach the comparative safety of the Sakarya River, some 30 miles (48 km) to the north and only 50 miles (80 km) from Ankara.[21]

The determining feature of the terrain was the river itself, which flows eastward across the plateau, suddenly curves north and then turns back westwards describing a great loop that forms a natural barrier. The river banks are awkward and steep, and bridges were few, there being only two on the frontal section of the loop. East of the loop, the landscape rises before an invader in rocky, barren ridges and hills towards Ankara. It was here in these hills, east of the river that the Turks dug in their defensive positions. The front followed the hills east of the Sakarya River from a point near Polatlı southwards to where the Gök River joins the Sakarya, and then swung at rightangles eastwards following the line of the Gök River. It was an excellent defensive ground.[22]

For the Greeks, the question on whether to dig in and rest on their previous gains, or to advance towards Ankara in great effort and destroy the Army of the Grand National Assembly was difficult to resolve, posing the eternal problems that the Greek staff had to deal with since the beginning of the war. The dangers of extending the lines of communications still further in such an inhospitable terrain that killed horses, caused vehicles to break down and prevented the movement of heavy artillery were obvious. The present front that gave the Greeks the control of the essential strategic railway was tactically most favourable. But because the Army of the Grand National Assembly had escaped encirclement at Kütahya, nothing had been settled; therefore the temptation of achieving a “knock-out-blow” became irresistible.[23]

Battle

On August 10, Constantine finally committed his forces to an assault against the Sakarya Line. The Greeks marched hard for nine days before making contact with the enemy. This march included an outflanking manoeuvre through the northern part of Anatolia through the Salt Desert where food and water scarcely existed, so the advancing infantry foraged the poor Turkish villages for maize and water or obtain meat from the flocks which were pastured on the fringe of the desert.[24]

On August 23, battle was finally joined when Greeks made contact with advanced Turkish positions south of the Gök River. The Turkish Staff had made their headquarters at Polatlı on the railway a few miles east of the coast of the Sakarya River and the troops were prepared to resist.

On August 26, the Greeks attacked all along the line. Crossing the shallow Gök, the infantry fought its way step up onto the heights where every ridge and hill top had to be stormed against strong entrenchments and withering fire.

By September 2 the commanding heights of the key Mount Chal were in Greek hands, but once the Greek enveloping movement against the Turkish left flank had failed, the Battle of the Sakarya River descended to a typical head-on confrontation of infantry, machine-guns and artillery.[25] The Greeks launched their main effort in the centre, pushing forward some 10 miles (16 km) in 10 days, through the Turkish Second Line of defense. Some Greek units came as close as 31 miles (50 km) to the city of Ankara.[26] This was the summit of their achievement in the Asia Minor Campaign.[24]

For days during the battle neither ammunition nor food had reached the front, owing to successful harassment of the Greek lines of communications and raids behind the Greek lines by Turkish cavalry. All the Greek troops were committed to the battle, while fresh Turkish drafts were still arriving throughout the campaign in response to the Nationals mobilization. For all these reasons the impetus of the Greek attack was gone. For a few days there was a lull in the fighting in which neither exhausted army could press an attack.[27] The Greek king Constantine I, who commanded the battle personally, was almost taken prisoner by a Turkish patrol.[28]

Astute as ever at the decisive moment, Mustafa Kemal assumed personal command and led a small counter-attack against the Greek left and around the Mount Chal on September 8. The Greek line held and the attack itself achieved a limited military success,[29] but in fear that this presaged a major Turkish effort to outflank their forces as the severity of winter was approaching, Constantine broke off the Greek assault on September 14, 1921.[30]

Consequently, Anastasios Papoulas ordered a general retreat towards Eskişehir and Afyonkarahisar. The Greek troops evacuated the Mount Chal which had been taken at such cost and retired unmolested across the Sakarya River to the positions they have left a month before, taking with them their guns and equipment. In the line of the retreating army nothing was left that could benefit the Turks. Railways and bridges were blown up, the same way villages were burnt.[31] After Greek retreat, Turkish forces managed to retake Sivrihisar on September 20, Aziziye on September 22, Bolvadin and Çay on September 24.

Aftermath

The retreat from Sakarya marked the end of the Greek hopes of imposing settlement on Turkey by force of arms. In May 1922 General Papoulas and his complete staff resigned and was replaced by General Georgios Hatzianestis, who proved much more inept than his predecessor.[25]

On the other hand, Mustafa Kemal returned in triumph to Ankara where the Grand National Assembly awarded him the rank of Field Marshal of the Army, as well as the title of Gazi rendering honours as the saviour of the Turkish nation.[32]

According to the speech that was delivered years later before the same National Assembly at the Second General Conference of the Republican People's Party which took part from October 15 to October 20, 1927; Kemal was said to have ordered that " ... not an inch of the country should be abandoned until it was drenched with the blood of the citizens...," upon realizing that the Turkish army was losing ground rapidly, with virtually no natural defenses left between the battle line and Ankara.[33][34]

Lord Curzon argued that the military situation became a stalemate with time tending in favour of the Turks. The Turkish position within the British views was improving. In his opinion, the Turkish Nationalists were at that point more ready to treat.[35]

After this, the Ankara government signed the Treaty of Kars with the Russians, and the most important Treaty of Ankara with the French, thus reducing the enemy's front notably in the Cilician theatre and concentrating against the Greeks on the West.[36]

For the Turkish troops it was the turning point of the war, which would develop in a series of victorious clashes against the Greeks, driving out the invaders from the whole Asia Minor in the Turkish War of Independence.[37] The Greeks could do nothing but retreat.

As by August 26. 1922 Turkish offensive started with Battle of Dumlupınar. Kemal dispatched his army on a drive to the coast of the Aegean Sea pursuing the shattered Greek army, which would culminate in the direct assault of Smyrna between September 9 and 11th 1922.

The war would be over and sealed with the defeat of the Greeks, formalized by the Treaty of Lausanne on 24 July 1923.

Gallery

Evacuation of wounded Greek soldiers

Evacuation of wounded Greek soldiers Collection of Turkish prisoners

Collection of Turkish prisoners Greek infantry awaits order to attack

Greek infantry awaits order to attack Greek infantry approaches the heights of Polatlı

Greek infantry approaches the heights of Polatlı Evzones attack

Evzones attack Bodies of killed Greek soldiers after the Battle of Sakarya

Bodies of killed Greek soldiers after the Battle of Sakarya Greek lithograph of the era, depicting the battle as a Greek victory

Greek lithograph of the era, depicting the battle as a Greek victory Mustafa Kemal and Salih (Bozok) at Duatepe Hill, observing enemy positions

Mustafa Kemal and Salih (Bozok) at Duatepe Hill, observing enemy positions "Anatolia's present to Greece on the occasion of the new year". Political cartoon published one month after the battle

"Anatolia's present to Greece on the occasion of the new year". Political cartoon published one month after the battle

References

- Michael Llewellyn Smith "Ionian Vision" Hurst & Company London 1973 ISBN 1-85065-413-1, p. 234

- Spencer C. Tucker, (2019), Middle East Conflicts from Ancient Egypt to the 21st Century, p. 1100

- Michael Llewellyn Smith "Ionian Vision" Hurst & Company London 1973 ISBN 1-85065-413-1, p. 227–232

- Battle of Sakarya Archived June 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Turkish General Staff, retrieved: 12 Ağustos 2009.

- Zeki Sarıhan: Kurtuluş Savaşı günlüğü: açıklamalı kronoloji. Sakarya savaşı'ndan Lozan'ın açılışına (23 Ağustos 1921-20 Kasım 1922) (engl.: Diary of the War of Independence: commented chronology. From the Battle of Sakarya to the opening of Lausanne (23 August 1921-20 November 1922)), Türk Tarih Kurumu yayınları (publishing house), 1996, ISBN 975-16-0517-2, page 62.

- Celâl Erikan: 100 [i.e. Yüz] soruda Kurtuluş Savaşımızın tarihi, Edition I, Gerçek Yayınevi, 1971, İstanbul, page 166. (in Turkish)

- Σαγγάριος 1921, Η επική μάχη που σφράγησε την τύχη του Μικρασιατικού Ελληνισμού, Εκδόσεις Περισκόπιο, Ιούλιος 2008, ISBN 978-960-6740-45-9, page 32

- Campbell, Verity; Carillet, Jean-Bernard; Elridge, Dan; Gordon, Frances Linzee (2007). Turkey. Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-74104-556-8.

- Edmund Schopen: Die neue Türkei, Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag, 1938, page 95. (in German)

- Sean McMeekin, The Berlin-Baghdad Express: The Ottoman Empire and Germany's Bid for World Power , Harvard University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-674-05739-5, p. 302.

- Osman Faruk Loğoğlu, İsmet İnönü and the Making of Modern Turkey, İnönü Vakfı, 1997, ISBN 978-975-7951-01-8, p. 56.

- Archived 2019-02-04 at the Wayback Machine Sakarya Meydan Muharebesi’nin Yankıları (Melhâme-i Kübrâ Büyük Kan Seli veya büyük Savaş Alanı)

- Revue internationale d'histoire militaire Volumes 46–48, International Committee of Historical Sciences. Commission of comparative military history, 1980, page 222

- International review of military history (Volume 50), International Committee of Historical Sciences. Commission d'histoire militaire comparée, 1981, page 25.

- Dominic Whiting, Turkey Handbook, Footprint Travel Guides, 2000, ISBN 1-900949-85-7, page 445.

- Young Turk, Moris Farhi, Arcade Publishing, 2005, ISBN 978-1-55970-764-0, page 153.

- Kevin Fewster, Vecihi Başarin, Hatice Hürmüz Başarin, A Turkish view of Gallipoli: Çanakkale, Hodja, 1985, ISBN 0-949575-38-0, page 118.

- William M. Hale Turkish foreign policy, 1774–2000, Routledge, 2000, ISBN 0-7146-5071-4, page 52.

- Michael Dumper, Bruce E. Stanley: Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: a historical encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, 2007, ISBN 1-57607-919-8, page 38.

- Kate Fleet, Suraiya Faroqhi, Reşat Kasaba: The Cambridge History of Turkey (Volume 4), Cambridge University Press, 2008, ISBN 0-521-62096-1, page 138.

- Christopher Chant "Warfare of the 20th. Century – Armed Conflicts Outside the Two World Wars" Chartwell Books Inc. New Jersey 1988. ISBN 1-55521-233-6, p. 22

- Michael Llewellyn Smith, p. 227

- Michael Llewellyn Smith, p. 228

- Michael Llewellyn Smith, p. 233

- Christopher Chant "Warfare of the 20th. Century – Armed Conflicts Outside the Two World Wars" Chartwell Books Inc. New Jersey 1988. ISBN 1-55521-233-6, p. 23

- Österreichische Militärische Zeitschrift, Verlag C. Ueberreuter, 1976, page 131. (in German)

- Michael Llewellyn Smith, p. 233–234

- Johannes Glasneck: Kemal Atatürk und die moderne Türkei, 2010, Ahriman-Verlag GmbH, ISBN 3894846089, page 133. (in German)

- Michael Llewellyn Smith "Ionian Vision" Hurst & Company London 1973 ISBN 1-85065-413-1, pg. 233–234

- Christopher Chant, p. 23

- Michael Llewellyn Smith, p. 234

- Shaw, Stanford Jay (1976), "History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey", Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-21280-9, p. 357

- Turkish: Dedim ki: «Hatt-ı müdafaa yoktur, Saht-ı müdafaa vardır. O satıh, bütün vatandır. Vatanın, her karış toprağı, vatandaşın kaniyle ıslanmadıkça, terkonuamaz. Onun için küçük, büyük her cüz-i tam, bulunduğu mevziden atılabilir. Fakat küçük, büyük her cüz-i tam, ilk durabildiği noktada, tekrar düşmana karşı cephe teşkil edip muharebeye devam eder. Yanındaki cüz-, tamın çekilmeğe mecbur olduğunu gören cüz-i tamlar, ona tâbi olamaz. Bulunduğu mevzide nihayete kadar sebat ve mukavemet mecburdur.», Gazi M. Kemal, Nutuk-Söylev, Cilt II: 1920–1927, Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, ISBN 975-16-0195-9, pp. 826–827.

- English: I said that there was no line of defence but a plain of defence, and that this plain was the whole of the country. Not an inch of the country should be abandoned until it was drenched with the blood of the citizens..., A speech Delivered by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, 1927, Ministry of Education Print. Plant, 1963, p. 521.

- Michael Llewellyn Smith, p. 240

- Michael Llewellyn Smith, p. 241

- Shaw, Stanford Jay; , p. 362

Notes

- Although Turkish casualties state 5,639 deserters and 8,089 missing, these two casualty figures belong to the period between the Battle of Kütahya–Eskişehir and the Battle of Sakarya.[6]