Responsibility for the great fire of Smyrna

The question of who was responsible for starting the great fire of Smyrna continues to be debated, with Turkish sources mostly attributing responsibility to Greeks or Armenians and vice versa.[1]

Sources claiming Turkish responsibility

George Horton's account

George Horton was the U.S. Consul General of Smyrna. He was compelled to evacuate Smyrna on 13 September, and arrived in Athens on 14 September.[2] In 1926, he published his own account of what happened in Smyrna, titled The Blight of Asia. He included testimony from a number of eyewitnesses and quoted a number of contemporary scholars. Horton's account states that the last of the Greek soldiers had abandoned Smyrna during the evening of 8 September[3] since it was known in advance that Turkish soldiers would arrive on 9 September.[4]

Origins of the Fire

Horton noted that Turkish soldiers set the fire, on 11 September,

I returned to Smyrna later and was there up until the evening of September 11, 1922, on which date the city was set on fire by the army of Mustapha Khemal, and a large part of its population done to death, and I witnessed the development of that Dantesque tragedy, which possesses few, if any parallels in the history of the world first cleared the Armenian quarter and then torched a number of houses simultaneously behind the American Inter-Collegiate Institute. They waited for the wind to blow in the right direction, away from the homes of the Muslim population, before starting the fire. This report is backed up by the eyewitness testimony of Miss Minnie Mills, the dean of the Inter-Collegiate Institute:[5] “I could plainly see the Turks carrying the tins of petroleum into the houses, from which, in each instance, fire burst forth immediately afterward. There was not an Armenian in sight, the only persons visible being Turkish soldiers of the regular army in smart uniforms.” This was confirmed by the eyewitness report of Mrs King Birge, the wife of an American missionary, who viewed events from the tower of the American College at Paradise.[5]

Contemporary scholars quoted

Horton quoted contemporary scholars within his account, including the historian William Stearns Davis: "The Turks drove straight onward to Smyrna, which they took (9 September 1922) and then burned."[6] Also, Sir Valentine Chirol, lecturer at the University of Chicago: "After the Turks had smashed the Greek armies they turned the essentially Greek city (Smyrna) into an ash heap as proof of their victory."[6][7]

Summary of the destruction of Smyrna

The following is an abridged summary of notable events in the destruction of Smyrna described in Horton's account:[9]

- Turkish soldiers cordoned off the Armenian quarter during the massacre. Armed Turks massacred Armenians and looted the Armenian quarter.

- After their systematic massacre, uniformed Turkish soldiers set fire to Armenian buildings using tins of petroleum and flaming rags soaked in flammable liquids.

- Soldiers planted small bombs under paving slabs around the Christian parts of the city to take down walls. One of the bombs was planted near the American Consulate and another at the American Girls' School.

- The fire was started on 13 September. The last Greek soldiers had evacuated Smyrna on 8 September. The Turkish Army was in full control of Smyrna from 9 September. All Christians remaining in the city who evaded massacre stayed within their homes, fearing for their lives. The burning of the homes forced Christians into the streets. Horton personally witnessed this.

- The fire was initiated at one edge of the Armenian quarter when a strong wind was blowing toward the Christian part of town and away from the Muslim part of town. Citizens of the Muslim quarter were not involved in the catastrophe. The Muslim quarter celebrated the arrival of the Turkish Army.

- Turkish soldiers guided the fire through the modern Greek and European section of Smyrna by pouring flammable liquids into the streets. These were poured in front of the American Consulate to guide the fire, as witnessed by C. Clafun David, the Chairman of the Disaster Relief Committee of the Red Cross (Constantinople Chapter) and others who were standing at the door of the consulate. Mr Davis testified that he put his hands in the mud where the flammable liquid was poured and indicated that it smelled like mixed petroleum and gasoline. The soldiers who were observed doing this had started from the quay and proceeded towards the fire, thus ensuring the rapid and controlled spread of the fire.

- Dr Alexander Maclachlan, the president of the American College, together with a sergeant of the American Marines, was stripped and beaten with clubs by Turkish soldiers. In addition, a squad of American Marines was fired on.

Charles Dobson

Charles Dobson, an Anglican chaplain in Smyrna, was convinced that the Turks started the fire. He wrote multiple reports stating this belief in response to Turkish denial of responsibility.[10]

American eyewitnesses

One of the witnesses in Marjorie Housepian Dobkin's account was the American industrial engineer Mark Prentiss, a foreign trade specialist in Smyrna, who was also acting as a freelance correspondent for the New York Times. He was an eyewitness to many of the events which occurred in Smyrna. He was initially quoted in The New York Times as putting the blame on the Turkish military. Prentiss arrived in Smyrna 8 September 1922, one day before the Turkish Army marched into Smyrna. He was a special representative of the Near East Relief (an American charity organization whose purpose was to watch over and protect Armenians during the war). He arrived on the destroyer USS Lawrence, under the command of Captain Wolleson. His superior was Rear Admiral Mark Lambert Bristol, U.S. High Commissioner to the Ottoman Empire from 1919 to 1927, present in Constantinople. Bristol was intent on securing economic concessions for the United States from Turkey and made a concerted effort to prevent any news report to appear to show any favor to the Armenians or Greeks. He once remarked that "I hate the Greeks. I hate the Armenians and I hate the Jews. The Turks are fine fellows."[11]

The former American vice-consul to Persia was so incensed by Bristol's efforts to stifle news coming out of Smyrna, that he took out an op-ed in New York Times to write, "The United States cannot afford to have its fair name besmirched and befouled by allowing such a man to speak for the American soul and conscience."[11]

Prentiss initial published statements were as follows:[12]

Many of us personally saw – and are ready to affirm the statement – Turkish soldiers often directed by officers throwing petroleum in the street and houses. Vice-Consul Barnes watched a Turkish officer leisurely fire the Custom House and the Passport Bureau while at least fifty Turkish soldiers stood by. Major Davis saw Turkish soldiers throwing oil in many houses. The Navy patrol reported seeing a complete horseshoe of fires started by the Turks around the American school.

Critics of Prentiss point out that Prentiss changed his story, giving two very different statements of events at different times.[12] Initially, Prentiss had cabled his account, which was printed in The New York Times on 18 September 1922 as "Eyewitness Story of Smyrna's Horror; 200,000 Victims of Turks and Flames". Upon his return to the United States, he was pressured by Admiral Bristol to put a different version on record. Prentiss then claimed that it was the Armenians who had set the fire. (the New York Times partially disavowed his first report in an article on 14 November.)

Bristol reported that during the Turkish capture of Smyrna and the ensuing fire the number of deaths due to killings, fire, and execution did not exceed 2,000.[13] He is the only one to offer such a low estimate of fatalities.

René Puaux

A near-contemporaneous account is given by René Puaux, correspondent of the respected Paris newspaper Le Temps, who had been posted in Smyrna since 1919. Based on multiple eyewitness accounts, he concluded that "by Wednesday [13 September] the putrefaction of the bodies, left unattended since the 9th in the evening, became untolerable, explaining what happened. The Turks, having pillaged the Armenian quarter and massacred a great portion of its inhabitants, resorted to fire to erase the trace of their actions."[14] He also quoted a telegraph by Major General F. Maurice, special correspondent for the Daily News in Constantinople, concluding that "The fire started on the 13th, in the afternoon, in the Armenian quarter, but the Turkish authorities did nothing serious to stop it. The next day eyewitnesses saw a large number of Turkish soldiers throwing gasoline and setting houses on fire. The Turkish authorities could have prevented the fire from reaching the European quarters. Turkish soldiers, acting deliberately, are the primary cause of the terrible spread of the disaster."[14]

Professor Rudolf J. Rummel

Genocide scholar Rudolph J. Rummel blames the Turkish side for the "systematic firing" in the Armenian and Greek quarters of the city. Rummel argues that after the Turks recaptured the city, Turkish soldiers and Muslim mobs shot and hacked to death Armenians, Greeks, and other Christians in the streets of the city; he estimates the victims of these massacres, by giving reference to the previous claims of Dobkin, at about 100,000 Christians.[15]

Historians Lowe and Dockrill

C.J. Lowe and M.L. Dockrill attribute blame for the fire to the "Kemalists," saying it was in retaliation for the earlier Greek occupation of Smyrna and was an attempt to push the Greeks out:[16]

The short-sightedness of both Lloyd George and President Wilson seems incredible, explicable only in terms of the magic of Venizelos and an emotional, perhaps religious, aversion to the Turks. For Greek claims were at best debatable, perhaps a bare majority, more likely a large minority in the Smyrna Vilayet, which lay in an overwhelmingly Turkish Anatolia. The result was an attempt to alter the imbalance of populations by genocide, and the counter determination of Nationalists to erase the Greeks, a feeling which produced bitter warfare in Asia Minor for the next two years until the Kemalists took Smyrna in 1922 and settled the problem by burning down the Greek quarter.

Giles Milton

British author Giles Milton's Paradise Lost: Smyrna 1922 (2008) is a graphic account of the sack of Smyrna (modern İzmir) in 1922 recounted through the eyes of the city's Levantine community. Milton's book is based on eyewitness accounts of those who were there, making use of unpublished diaries and letters written by Smyrna's Levantine elite:[17] He contends that their voices are among the few impartial ones in a highly contentious episode of history.

Paradise Lost chronicles the violence that followed the Greek landing through the eyewitness accounts of the Levantine community. The author offers a reappraisal of Smyrna's first Greek governor, Aristidis Stergiadis, whose impartiality towards both Greeks and Turks earned him considerable enmity amongst the local Greek population.

The third section of Paradise Lost is a day-by-day account of what happened when the Turkish army entered Smyrna. The narrative is constructed from accounts written principally by Levantines and Americans who witnessed the violence first hand, in which the author seeks to apportion blame and discover who started the conflagration that was to cause the city's near-total destruction. According to Milton, the fire was started by the Turkish army, who brought in thousands of barrels of oil and poured them over the streets of Smyrna, with the exception of the Turkish quarter. The book also investigates the role played by the commanders of the 21 Allied warships in the bay of Smyrna, who were under orders to rescue only their own nationals, abandoning to their fate the hundreds of thousands of Greeks and Armenian refugees gathered on the quayside.

Falih Rıfkı Atay

Falih Rıfkı Atay, a Turkish journalist and author of national renown, is quoted as having lamented that the Turkish army had burnt Smyrna to the ground in the following terms:

Gavur [infidel] İzmir burned and came to an end with its flames in the darkness and its smoke in daylight. Were those responsible for the fire really the Armenian arsonists as we were told in those days? ... As I have decided to write the truth as far as I know I want to quote a page from the notes I took in those days. 'The plunderers helped spread the fire ... Why were we burning down İzmir? Were we afraid that if waterfront konaks, hotels and taverns stayed in place, we would never be able to get rid of the minorities? When the Armenians were being deported in the First World War, we had burned down all the habitable districts and neighbourhoods in Anatolian towns and cities with this very same fear. This does not solely derive from an urge for destruction. There is also some feeling of inferiority in it. It was as if anywhere that resembled Europe was destined to remain Christian and foreign and to be denied to us.[18]

If there were another war and we were defeated, would it be sufficient guarantee of preserving the Turkishness of the city if we had left Izmir as a devastated expanse of vacant lots? Were it not for Nureddin Pasha, whom I know to be a dyed-in-the-wool fanatic and rabblerouser, I do not think this tragedy would have gone to the bitter end. He has doubtless been gaining added strength from the unforgiving vengeful feelings of the soldiers and officers who have seen the debris and the weeping and agonized population of the Turkish towns which the Greeks have burned to ashes all the way from Afyon.[19]

Falih Rifki Atay implied Nureddin Pasha was the person responsible for the fire in his account: "At the time it was said that Armenian arsonists were responsible. But was this so? There were many who assigned a part in it to Nureddin Pasha, commander of the First Army, a man whom Kemal had long disliked..."[20]

Professor Biray Kolluoğlu Kırlı

Biray Kolluoğlu Kırlı, a Turkish professor of Sociology at Bogazici University, published a paper in 2005 in which she argues that Smyrna was burned by the Turkish Army to create a Turkish city out of the cosmopolitan fabric of the old city.[21]

Reşat Kasaba's essay

Turkish historian Resat Kasaba noted in a short essay that various pro-Turkish sources offer different and even contradicting explanations for this event. Some of them completely ignore the event or they claim that there was not a fire at all. Additional pro-Turkish accounts claim that the Greeks set the fire, but others suggest that both Greeks and Turks did it.[22] The local population feared violence by Turkish troops, as soon as they entered the city, as retaliation for the earlier scorched earth policy of the Greek Army during the last stage of the war.[23]

Sources claiming Greek or Armenian responsibility

Mustafa Kemal's telegram

On 17 September, when the massacre and the fire in the city had come to an end, Mustafa Kemal, Commander-in-Chief of the Turkish armies, sent the Minister of Foreign Affairs Yusuf Kemal the following telegram, describing the official version of events in the city:[24][25]

FROM COMMANDER IN CHIEF GAZI MUSTAFA KEMAL PASHA TO THE MINISTER OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS YUSUF KEMAL BEY

Tel. 17.9.38 (1922) (Arrived 4.10.38)

To be transmitted with care. Important and urgent.

Find hereunder the instruction I sent to Hamid Bey with Admiral Dumesmil, who left for İstanbul today.

Commander-In-Chief

Mustafa KEMAL

Copy To Hamid Bey,

1. It is necessary to comment on the fire in İzmir for future reference.

Our army took all the necessary measures to protect İzmir from accidents, before entering the city. However, the Greeks and the Armenians, with their pre-arranged plans have decided to destroy İzmir. Speeches made by Chrysóstomos at the churches have been heard by the Muslims, the burning of İzmir was defined as a religious duty. The destruction was accomplished by this organization. To confirm this, there are many documents and eyewitness accounts. Our soldiers worked with everything that they have to put out the fires. Those who attribute this to our soldiers may come to İzmir personally and see the situation. However, for a job like this, an official investigation is out of the question. The newspaper correspondents of various nationalities presently in İzmir are already executing this duty. The Christian population is treated with good care and the refugees are being returned to their places.[26]

Grescovich Report

Paul Grescovich, the chief of the Smyrna Fire Department and seen by Prentiss as "a thoroughly reliable witness", put the blame on Greeks and Armenians. He reported that Smyrna had seen an abnormal amount of fires in the first week of September, some of which were arson cases. Once Turkish troops captured Smyrna, Gresovich asked for more men and equipment to fight the fires. The Turkish authorities didn't provide additional support immediately. They first arrested the Greek firemen, who made up about a fifth of Grescovich's force. The fire department went a few days with reduced staff. On the 11th and 12th, the Turkish army assisted the firefighters in extinguishing fires across the city.[27]

At the same time, Grescovich reported, Armenians were caught setting fires. He stated especially that "his own firemen, as well as Turkish guards, had shot down many Armenian young men disguised either as women or as Turkish irregular soldiers, who were caught setting fires during Tuesday night [12 September] and Wednesday [13 September] morning". Prentiss reports Grescovich as stating that at least six fires were reported around freight terminal warehouses and the Adine railroad passenger station at 11:20, five more around the Turkish-occupied Armenian hospital at 12:00 and nearly at the same time at the Armenian Club, and several at the Cassaba railroad station. Grescovich then asked the military authorities for help, but got no assistance until 6 pm when he was given soldiers who, two hours later, started to blow up buildings to prevent the fire from spreading.[27]

Letters of Johannes Kolmodin

Johannes Kolmodin, a Swedish Orientalist scholar, was studying in Smyrna in those days. He wrote that the Greek army was responsible for the fire, as well as fires in 250 Turkish villages.[28]

Contemporary newspapers and witnesses

A French journalist who had covered the Turkish War of Independence arrived in Smyrna shortly after the flames had died down. He wrote:[29]

The first defeat of the nationalists had been this enormous fire. Within forty-eight hours, it had destroyed the only hope of immediate economic recovery. For this reason, when I heard people accusing the winners themselves of having provoked it to get rid of the Greeks and Armenians who still lived in the city, I could only shrug off the absurdity of such talk. One had to know the Turkish leaders very little indeed to attribute to them so generously a taste for unnecessary suicide.

Bilge Umar, an individual witness, art historian and long-time inhabitant of Smyrna, suggested that both Turkish and the Armenian sides were guilty for the fire: "Turks and Armenians are equally to blame for this tragedy. All the sources show that the Greeks did not start the fire as they left the city. The fire was started by fanatical Armenians. The Turks did not try to stop the fire."[30]

Non-contemporary sources

Donald Webster's version

According to US scholar Donald Webster, who taught at the International College in Izmir between 1931 and 1934:

All the world heard about the great fire which destroyed much of beautiful Izmir. While every partisan accuses enemies of the incendiarism, the preponderance of impartial opinion blames the terror-stricken Armenians, who had bet their money on the wrong horse – a separatist national rather than a cultural individuality within the framework of the new, laïque Turkey."[32]

Lord Kinross's study

Devoting an entire chapter of his biography of Atatürk to the fire, Lord Kinross argues:

The internecine violence led, more or less by accident, to the outbreak of a catastrophic fire. Its origins were never satisfactorily explained. Kemal maintained to Admiral Dumesnil that it had been deliberately planned by an Armenian incendiary organization, and that before the arrival of the Turks speeches had been made in churches, calling for the burning of the city as a sacred duty. Fuel for the purpose had been found in the houses of Armenian women, and several incendiaries had been arrested. Others accused the Turks themselves of deliberately starting the fire under the orders or at least connivance of Nur-ed-Din Pasha, who had a reputation for fanaticism and cruelty. Most probably it started when the Turks, rounding up the Armenians to confiscate their arms, besieged a band of them in a building in which they had taken refuge. Deciding to burn them out, they set it alight with petrol, placing cordon of sentries around to arrest or shoot them as they escaped. Meanwhile the Armenians started other fires to divert the Turks from their main objective. The quarter was on the outskirts of the city. But a strong wind, for which they had not allowed, quickly carried flames towards the city. By the early evening several other quarters were on fire, and a thousand homes, built flimsily of lath and plaster, had been reduced to ashes. The flames were being spread by the looters, and doubtless also by Turkish soldiers, paying off scores. The fire brigade was powerless to cope with such a conflagration, and at Ismet's headquarters the Turks alleged that its hose pipes had been deliberately severed. Ismet himself chose to declare that the Greeks had planned to burn the city.[33]

Other accounts

In an article published in Current History Colonel Rachid Galib stated that H. Lamb, the British Consul General at Smyrna, reported that he "had reason to believe that Greeks in concert with Armenians had burned Smyrna".[34]

Historiography

The question of who was responsible for starting the great fire of Smyrna continues to be debated, with Turkish sources mostly attributing responsibility to Greeks or Armenians and vice versa.[35][36]

A number of studies have been published on the Smyrna fire. Professor of literature Marjorie Housepian Dobkin's Smyrna 1922, a meticulously documented chronicle of the events according to the New York Times,[37] concludes that the Turkish Army systematically burned the city and killed Christian Greek and Armenian inhabitants. Her work is based on extensive eyewitness testimony from survivors, Allied troops sent to Smyrna during the evacuation, foreign diplomats, relief workers, and Turkish eyewitnesses. A study by historian Niall Ferguson comes to the same conclusion. Historian Richard Clogg categorically states that the fire was started by the Turks following their capture of the city.[38] In his book Paradise Lost: Smyrna 1922, Giles Milton addresses the issue of the Smyrna Fire through original material (interviews, unpublished letters, and diaries) from the Levantine families of Smyrna, who were mainly of British origin. All the documents collected by the author during this research are deposited in Exeter University Library.[39] The conclusion of the author is that it was Turkish soldiers and officers who set the fire, most probably acting under direct orders. British scholar Michael Llewellyn-Smith, writing on the Greek administration in Asia Minor, also concludes that the fire was "probably lit" by the Turks as indicated by what he calls "what evidence there is".[40]

American historian Norman Naimark has evaluated the evidence regarding the responsibility of the fire. He agrees with the view of American Lieutenant Merrill that it was in Turkish interests to terrorize Greeks into leaving Smyrna with the fire, and points out to the "odd" fact that the Turkish quarter was spared from the fire as a factor suggesting Turkish responsibility. However, he points out that there is no "solid and substantial evidence" of this and that it can be argued that burning the city was against Turkish interests and was unnecessary. He also suggests that the responsibility may lie with Greeks and Armenians as they "had own their good reasons", pointing out to the "Greek history of retreating" and "Armenian attack in the first day of the occupation". But normally this considered as an escapism or an excuse for their failure to help the Christians and shift to shift the responsibility to the victims[41]

Horton and Housepian are criticized by Heath Lowry and Justin McCarthy, who argue that Horton was highly prejudiced and Housepian makes an extremely selective use of sources.[42] Lowry and McCarthy are members of the Institute of Turkish Studies and have in turn been strongly criticized by other scholars for their denial of the Armenian Genocide[43][44][45][46] and McCarthy has been described by Michael Mann as being on "the Turkish side of the debate."[47] Horton, however, has been criticised as anti-Turkish by a number of other scholars. Professor Biray Kolluoğlu Kırlı has accused Horton of having a "crudely explicit" anti-Turkish bias,[48] while in his review of Horton's work, Professor Emeritus Peter M. Buzanski has attributed Horton's anti-Turkish stance to his well-known "fanatic" philhellenism and his wife being Greek, and written "During the Turkish capture of Smyrna, at the end of the Greco-Turkish War, Horton suffered a breakdown, resigned from the diplomatic service, and spent the balance of his life writing anti-Turkish, pro-Greek books."[49] Brian Coleman, reviewing Horton's work, has characterised it as "a demonization of Muslims, in general, and of Turks, in particular" and stated that Horton wrote not as historian, but as publicist.[50]

Turkish author and journalist Falih Rifki Atay, who was in Smyrna at the time, and the Turkish professor Biray Kolluoğlu Kırlı agreed that the Turkish Army was responsible for the destruction of Smyrna in 1922. More recently, a number of non-contemporary scholars, historians, and politicians have added to the history of the events by revisiting contemporary communications and histories. Leyla Neyzi, in her work on the oral history regarding the fire, makes a distinction between Turkish nationalist discourse and local narratives. In the local narratives, she points out to the Turkish forces being held responsible for at least not attempting to extinguish the fire effectively, or, at times, being held responsible for the fire itself.[51]

Other accounts contradict some of the facts presented in the above works. These include a telegram sent by Mustafa Kemal, articles in contemporary newspapers, and a short non-contemporary essay by Turkish historian Reşat Kasaba of the University of Washington, who briefly describes events without making clear accusations.[52]

The accounts of Jewish teachers in Smyrna, letters of Johannes Kolmodin (a Swedish Orientalist who was in Smyrna at the time), and Paul Grescovich say that Greeks or Armenians were responsible for the fire. R.A. Weight stated that "his clients showed that the fire, in its origin, was a small accidental fire, though it eventually destroyed a large section of the town".[53]References

- Neyzi, Leyla (2008). "The Burning of Smyrna/ Izmir (1922) Revisited: Coming to Terms with the Past in the Present". The Past as Resource in the Turkic Speaking World: 23–42. doi:10.5771/9783956506888-23.

- Marketos, James L (2006). "George Horton: An American Witness in Smyrna" (PDF). AHI World. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- Horton, The Blight of Asia, p. 82.

- Horton, The Blight of Asia, p. 78.

- Horton, The Blight of Asia, p. 93.

- Horton, The Blight of Asia, p. 73.

- Chirol, Sir Valentine The Occident and the Orient, p. 58.

- Karavasilis, Niki (2010). The Whispering Voice of Smyrna. Dorrance Publishing. p. 250. ISBN 978-1434952974.

- Horton, The Blight of Asia, pp. 74–75.

- Hyslop, Joanna (2016). "'A brief and personal account': the evidence of Charles Dobson on the destruction of the city of Smyrna in September 1922". Modern Greek Studies (Australia and New Zealand). 0 (0). ISSN 1039-2831.

- Milton 2008, p. 350.

- Dobkin. Smyrna 1922, p. 71.

- Freely, John. Children of Achilles: the Greeks in Asia Minor since the days of Troy. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2009, p. 213.

- René Puaux, La mort de Smyrne (The Death of Smyrna), Editions de la Revue des Balkans, 4th edition (1922), p. 13 (in French)

- Irving Louis Horowitz; Rudolph J. Rummel (1994). "Turkey's Genocidal Purges". Death by Government. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56000-927-6., p. 233.

- C. J. Lowe, M. L Dockrill, The Mirage of Power, British Foreign Policy 1914–1922, Routledge, p. 347, ISBN 978-0-415-26597-3

- Adil, Alev (9 June 2008). "Paradise Lost: Smyrna 1922". The Independent. London.

- Falih Rifki Atay, Çankaya: Atatürk'un Dogumundan Olumune Kadar, Istanbul, 1969, 324–25

- The Atatürk I Knew: An Abridged Translation of F.R. Atay's Çankaya by Geoffrey Lewis. İstanbul: Yapı ve Kredi Bankası, 1981, p. 180.

- Quoted in Nicole and Hugh Pope, Turkey Unveiled: A History of Modern Turkey, Woodstock, N.Y.: Overlook Press, 2004, p. 58. ISBN 978-1-58567-581-4.

- Kirli, Biray Kolluoglu. Forgetting the Smyrna Fire, History Workshop Journal, No. 60, 2005, Oxford University Press, pp. 25–44.

- "İzmir 1922: A port city unravels" Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Reşat Kasaba, Washington University, pp. 5–6

- Kasaba, "İzmir 1922", p. 1

- Bilal Şimşir, 1981. Atatürk ile Yazışmalar (The Correspondence with Atatürk), Kültür Bakanlığı

- Karavasilis, Niki (2010). The Whispering Voices of Smyrna. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA: Red Lead Press. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-4349-6381-9. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- Niki Karavasilis, The Whispering Voices of Smyrna, Dorrance Publishing, 2010, ISBN 978-1-4349-6381-9, pp. 208–209.

- Lowry, Heath W. (1989). "Turkish History: On Whose Sources Will It Be Based? A Case Study on the Burning of İzmir" (PDF). Journal of Ottoman Studies. 9: 8–12.

- Özdalga, Elizabeth. The Last Dragoman: The Swedish Orientalist Johannes Kolmodin as Scholar, Activist and Diplomat (2006), Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul, p. 63

- Nicole and Hugh Pope, Turkey Unveiled : A History of Modern Turkey, Woodstock, N.Y. : Overlook Press, 2004, p. 58 ISBN 978-1-58567-581-4

- Leyla Neyzi, "Remembering Smyrna/Izmir Shared History, Shared Trauma," History & Memory, Vol. 20, No. 2 (Fall/Winter 2008), p. 117.

- "Aya Fotini". levantineheritage.com. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- Donald Everett Webster, The Turkey of Ataturk – Social Process in the Turkish Reformation, Philadelphia: American Academy of Political and Social Science, 1939, p. 96.

- Lord Kinross, Ataturk: A Biography of Mustafa Kemal, Father of Turkey, New York: William Morrow & Company, 1965, pp. 370–371.

- So quoted in Colonel Rachid Galib, "Smyrna During the Greek Occupation," Current History, V. 18 May 1923, p. 319.

- Neyzi, Leyla (2008). "The Burning of Smyrna/ Izmir (1922) Revisited: Coming to Terms with the Past in the Present". The Past as Resource in the Turkic Speaking World: 23–42. doi:10.5771/9783956506888-23. ISBN 9783956506888.

- Martoyan, Tehmine (2017). "The Destruction of Smyrna in 1922: An Armenian and Greek Shared Tragedy". In Shirinian, George N. (ed.). Genocide in the Ottoman Empire: Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks, 1913-1923. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-78533-433-7.

- "Smyrna 1922: The Destruction of a City—A Review of Marjorie Housepian Dobkin's Work by Chris and Mary Papoutsy". www.helleniccomserve.com. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- Clogg, Richard (20 June 2002). A Concise History of Greece. Cambridge University Press. pp. 94. ISBN 9780521004794.

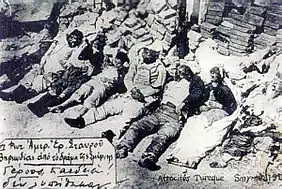

Refugees crowded on the waterfront at Smyrna on 13 September 1922 after fire had devastated much of the Greek, Armenian and Prankish [European] quarters of the city which the Turks had called Gavur Izmir or 'Infidel Izmir', so large was its non-Muslim population.

- Milton 2008, p. xx..

- Llewellyn Smith, Michael (1998). Ionian Vision: Greece in Asia Minor, 1919–1922. C. Hurst & Co. p. 308. ISBN 1850653682.

- Naimark, Norman M. (2002). Fires of Hatred. Harvard University Press. pp. 47–52. ISBN 978-0-674-00994-3.

- Lowry, Heath. "Turkish History: On Whose Sources Will it Be Based? A Case Study on the Burning of Izmir," The Journal of Ottoman Studies, IX, 1988; Justin McCarthy, Death and Exile. The Ethnic Cleansing of Ottoman Muslims. Princeton: Darwin Press, 1995, pp. 291–292, 316–317 and 327.

- Auron, Yair. The Banality of Denial: Israel and the Armenian Genocide. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 2003, p. 248.

- Charny, Israel W. Encyclopedia of Genocide, Vol. 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 1999, p. 163.

- Dadrian, Vahakn N. "Ottoman Archives and the Armenian Genocide" in The Armenian Genocide: History, Politics, Ethics. Richard G. Hovannisian (ed.) New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 1992, p. 284.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. "Denial of the Armenian Genocide in Comparison with Holocaust Denial" in Remembrance and Denial: The Case of the Armenian Genocide. Richard G. Hovannisian (ed.) Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1999, p. 210.

- Michael Mann, The Dark Side of Democracy: explaining ethnic cleansing, pp. 112–114, Cambridge, 2005 "... figures are derive[d] from McCarthy (1995: I 91, 162–164, 339), who is often viewed as a scholar on the Turkish side of the debate."

- Kırlı, Biray Kolluoğlu (2005). "Forgetting the Smyrna Fire" (PDF). History Workshop Journal. Oxford University Press. 60 (60): 25–44. doi:10.1093/hwj/dbi005. S2CID 131159279. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- Buzanski, Peter Michael (1960). Admiral Mark L. Bristol and Turkish-American Relations, 1919–1922. University of California, Berkeley. p. 176.

- Coleman, Brian, "George Horton: the literary diplomat", Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, Volume 30, Number 1, January 2006, pp. 81–93(13). DOI:10.1179/030701306X96618 (subscription required)

- Neyzi, Leyla (2008). "Remembering Smyrna/Izmir" (PDF). History & Memory. 20 (2). doi:10.2979/his.2008.20.2.106. S2CID 159560899. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- Reşat Kasaba"İzmir 1922: A port city unravels" Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Arts, York University.

- The Post Magazine and Insurance Monitor, Volume 85, Issue 2 (1924), Buckley Press, p. 2153