Bedford, Virginia

Bedford is an incorporated town and former independent city located within Bedford County in the U.S. state of Virginia. It serves as the county seat of Bedford County. As of the 2010 census, the population was 6,222.[5] It is part of the Lynchburg Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Bedford, Virginia | |

|---|---|

The town of Bedford on a typical fall evening. | |

.gif) Seal | |

| Nickname(s): The World's Best Little Town | |

| Motto(s): Life. Liberty. Happiness. | |

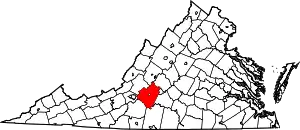

Location in Virginia | |

| Coordinates: 37°20′04″N 79°31′23″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Virginia |

| County | Bedford County |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Steve Rush |

| Area | |

| • Total | 8.75 sq mi (22.67 km2) |

| • Land | 8.72 sq mi (22.59 km2) |

| • Water | 0.03 sq mi (0.07 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,004 ft (306 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 6,222 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 6,597 |

| • Density | 756.28/sq mi (291.99/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 24523 |

| Area code(s) | 540 |

| FIPS code | 51-05544[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1498450[4] |

| Website | http://www.bedfordva.gov |

Known as the "place that sells itself," Bedford boasts the Blue Ridge Mountains to the North, Smith Mountain Lake to the South, Lynchburg to the East, and I-81/Roanoke to the West.

History

Bedford was originally known as Liberty, "named after the Colonial victory over Cornwallis at Yorktown." [6] Founded as a village in 1782, Liberty became Bedford County's seat of government, replacing New London which had become part of the newly formed Campbell County. Liberty became a town in 1839 and in 1890 changed its name to Bedford City. In 1912 Bedford reverted to town status, it resumed city status in 1968,[7] and once more it reverted to a town in 2013.[8]

In November 1923 the town was the site of an accidental mass poisoning. Nine men were killed after drinking apple cider served at the Elks National Home. A local farmer had produced the drink and stored in a barrel that had been used to hold a pesticide.[9]

Bedford is home to the National D-Day Memorial (despite the "National" in its name, the memorial is owned and operated by a non-governmental, non-profit, education foundation). The United States Congress warranted that this memorial would be the nation's D-Day Memorial and President Bill Clinton authorized this effort in September 1996. President George W. Bush dedicated this memorial as the nation's D-Day memorial on June 6, 2001. Bedford lost more residents per capita in the Normandy landings than any other American community. Nineteen soldiers from Bedford, whose 1944 population was about 3,200, were killed on D-Day. Three other Bedford soldiers died later in the Normandy campaign. Proportionally this community suffered the nation's most severe D-Day losses.[10]

Bedford was designated as an independent city in 1968, but remained the county seat of Bedford County. Its status as an independent city was ended on July 1, 2013, returning to a town within Bedford County.[11]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 6.9 square miles (18 km2), of which 6.9 square miles (18 km2) is land and 0.02 square miles (0.052 km2) (0.3%) is water.[12]

Bedford sits at the foot of the Peaks of Otter.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 722 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,208 | 67.3% | |

| 1880 | 2,191 | 81.4% | |

| 1890 | 2,897 | 32.2% | |

| 1900 | 2,416 | −16.6% | |

| 1910 | 2,508 | 3.8% | |

| 1920 | 3,243 | 29.3% | |

| 1930 | 3,713 | 14.5% | |

| 1940 | 3,973 | 7.0% | |

| 1950 | 4,061 | 2.2% | |

| 1960 | 5,921 | 45.8% | |

| 1970 | 6,011 | 1.5% | |

| 1980 | 5,991 | −0.3% | |

| 1990 | 6,073 | 1.4% | |

| 2000 | 6,299 | 3.7% | |

| 2010 | 6,222 | −1.2% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 6,597 | [2] | 6.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[13] 1790-1960[14] 1900-1990[15] 1990-2000[16] 2010-2012[5] | |||

At the 2000 census there were 6,299 people in 2,519 households, including 1,592 families, in the city. The population density was 914.5 persons per square mile (353.0/km2). There were 2,702 housing units at an average density of 392.3 per square mile (151.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 75.33% White, 22.38% Black or African American, 0.24% Native American, 0.57% Asian, 0.08% Pacific Islander, 0.24% from other races, and 1.16% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.89%.[17]

Of the 2,519 households, 27.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.0% were married couples living together, 17.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.8% were non-families. 33.0% of households were one person, and 15.7% were one person aged 65 or older. The average household size was 2.26 and the average family size was 2.87.

In the city the population was spread out, with 21.6% under the age of 18, 7.2% from 18 to 24, 27.8% from 25 to 44, 20.7% from 45 to 64, and 22.6% 65 or older. The median age was 41 years. For every 100 females, there were 90.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 85.4 males.

The median household income was $29,792 and the median family income was $35,023. Males had a median income of $31,668 versus $18,065 for females. The per capita income for the city was $15,423. About 11.4% of families and 12.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 19.4% of those under age 18 and 11.1% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

Top employers

According to the town's 2019 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[18] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wal-Mart | 362 |

| 2 | Centra Bedford Memorial Hospital | 358 |

| 3 | Bedford County Public Schools | 301 |

| 4 | Sam Moore Furniture LLC | 199 |

| 5 | Bedford Weaving Mills | 138 |

| 6 | Cintas | 130 |

| 7 | Lowes | 117 |

| 8 | Smyth Companies Bedford | 108 |

| 9 | English Meadows AKA Elks National Home | 87 |

| 10 | Food Lion | 65 |

Education

Bedford is served by Bedford County Public Schools, which operates Liberty High School and Liberty Middle School in the community. Fifteen elementary schools feed students into these and two other pairs of middle and high schools elsewhere in the county.[19]

Central Virginia Community College also has a branch campus in Bedford.[20]

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by mild, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Bedford has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[21]

Transportation

U.S. Route 221 runs through the town; and U.S. Route 460 circumvents the main part of town. State routes 43 and 122 converge onto the town.

Until the late 1960s there were three different Southern Railway/Norfolk & Western Railroad trains operating daily at Bedford station.[22]

- Birmingham Special—New York City to Birmingham, and branch to Memphis

- Pelican—New York to New Orleans

- Tennessean—Washington to Memphis

However, the newly restored Amtrak service to Roanoke does not make stops at Bedford.

International links

Bedford has a Friendship Treaty with:

Bedford maintains relationships with 11 communities on the Normandy Coast of France. One sister city, Trévières, France, sent Bedford an exact replica of its own World War I memorial statue. The face of the statue was damaged in World War II by artillery fire from US forces retaking the town. The Bedford statue also bears these wounds and is erected on the grounds of the National D-Day Memorial.

Notable people

- F.W. Caulkins, architect

- Lawrence Chambers, the first African American to command a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier and the first African American graduate of the Naval Academy to reach flag rank.[24]

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- Bedford County Sheriff's Office, Welcome to Bedford County!

- Bedford, Virginia Online, About the Town of Bedford Archived 2014-10-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Faulconer, Justin (July 1, 2013). "Bedford reversion to town becomes official today". The News & Advance. Lynchburg, VA. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- "VA Poisoned Cider Kills Nine at Elks Home". New York Times. 12 November 1923. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- Goldstein, Richard (23 April 2009). "Ray Nance, Last of the Bedford Boys, Dies at 94". The New York Times.

- Faulconer, Justin. "Bedford Reversion to Town Becomes Official Today". The News and Advance. newsadvance.com. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- "Town of Bedford CAFR". Retrieved 2020-09-05.

- "Home - Bedford County Public Schools". bedford.sharpschool.net. Retrieved 2016-09-25.

- "Bedford CVCC".

- Climate Summary for Bedford, Virginia

- Norfolk and Western Timetable, April 1966 documenting stops at the Bedford station http://streamlinermemories.info/South/N&W66-4TT.pdf

- Ivybridge International Links Archived 2008-07-08 at the Wayback Machine from the Ivybridge Town Guide

- Catherine Reef (1 January 2004). African Americans in the Military. Infobase Publishing. pp. 56–7. ISBN 978-1-4381-0775-2. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bedford, Virginia. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Bedford (Virginia). |