Oil paint

Oil paint is a type of slow-drying paint that consists of particles of pigment suspended in a drying oil, commonly linseed oil. The viscosity of the paint may be modified by the addition of a solvent such as turpentine or white spirit, and varnish may be added to increase the glossiness of the dried oil paint film. Oil paints have been used in Europe since the 12th century for simple decoration, but did not begin to be adopted as an artistic medium until the early 15th century. Common modern applications of oil paint are in finishing and protection of wood in buildings and exposed metal structures such as ships and bridges. Its hard-wearing properties and luminous colors make it desirable for both interior and exterior use on wood and metal. Due to its slow-drying properties, it has recently been used in paint-on-glass animation. Thickness of coat has considerable bearing on time required for drying: thin coats of oil paint dry relatively quickly.

History

The technical history of the introduction and development of oil paint, and the date of introduction of various additives (driers, thinners) is still—despite intense research since the mid 19th century—not well understood. The literature abounds with incorrect theories and information: in general, anything published before 1952 is suspect.[1] Until 1991 nothing was known about the organic aspect of cave paintings from the Paleolithic era. Many assumptions were made about the chemistry of the binders. Well known Dutch-American artist Willem De Kooning is known for saying “Flesh is the reason oil paint was invented”.[2]

First recorded use

The oldest known oil paintings date from 650 AD, found in 2008 in caves in Afghanistan's Bamiyan Valley, "using walnut and poppy seed oils."[3]

Classical and medieval period

Though the ancient Mediterranean civilizations of Greece, Rome, and Egypt used vegetable oils, there is little evidence to indicate their use as media in painting. Indeed, linseed oil was not used as a medium because of its tendency to dry very slowly, darken, and crack, unlike mastic and wax (the latter of which was used in encaustic painting).

Greek writers such as Aetius Amidenus recorded recipes involving the use of oils for drying, such as walnut, poppy, hempseed, pine nut, castor, and linseed. When thickened, the oils became resinous and could be used as varnish to seal and protect paintings from water. Additionally, when yellow pigment was added to oil, it could be spread over tin foil as a less expensive alternative to gold leaf.

Early Christian monks maintained these records and used the techniques in their own artworks. Theophilus Presbyter, a 12th-century German monk, recommended linseed oil but advocated against the use of olive oil due to its long drying time. Oil paint was mainly used as it is today in house decoration, as a tough waterproof cover for exposed woodwork, especially outdoors.

In the 13th century, oil was used to detail tempera paintings. In the 14th century, Cennino Cennini described a painting technique utilizing tempera painting covered by light layers of oil. The slow-drying properties of organic oils were commonly known to early painters. However, the difficulty in acquiring and working the materials meant that they were rarely used (and indeed the slow drying was seen as a disadvantage[4]).

Renaissance onwards

As public preference for naturalism increased, the quick-drying tempera paints became insufficient to achieve the very detailed and precise effects that oil could achieve. The Early Netherlandish painting of the 15th century saw the rise of panel painting purely in oils, or oil painting, or works combining tempera and oil painting, and by the 16th century easel painting in pure oils had become the norm. The claim by Vasari that Jan van Eyck "invented" oil painting, while it has cast a long shadow, is not correct, but van Eyck's use of oil paint achieved novel results in terms of precise detail and mixing colours wet-on-wet with a skill hardly equalled since. Van Eyck's mixture may have consisted of piled glass, calcined bones, and mineral pigments boiled in linseed oil until they reached a viscous state—or he may have simply used sun-thickened oils (slightly oxidized by Sun exposure).

The Flemish-trained or influenced Antonello da Messina, who Vasari wrongly credited with the introduction of oil paint to Italy,[5] does seem to have improved the formula by adding litharge, or lead (II) oxide. The new mixture had a honey-like consistency and better drying properties (drying evenly without cracking). This mixture was known as oglio cotto—"cooked oil." Leonardo da Vinci later improved these techniques by cooking the mixture at a very low temperature and adding 5 to 10% beeswax, which prevented darkening of the paint. Giorgione, Titian, and Tintoretto each may have altered this recipe for their own purposes.

Paint tube

The paint tube was invented in 1841 by portrait painter John Goffe Rand,[6] superseding pig bladders and glass syringes[7] as the primary tool of paint transport. Artists, or their assistants, previously ground each pigment by hand, carefully mixing the binding oil in the proper proportions. Paints could now be produced in bulk and sold in tin tubes with a cap. The cap could be screwed back on and the paints preserved for future use, providing flexibility and efficiency to painting outdoors. The manufactured paints had a balanced consistency that the artist could thin with oil, turpentine, or other mediums.

Paint in tubes also changed the way some artists approached painting. The artist Pierre-Auguste Renoir said, “Without tubes of paint, there would have been no impressionism.” For the impressionists, tubed paints offered an easily accessible variety of colors for their plein air palettes, motivating them to make spontaneous color choices.

Carrier

Characteristics

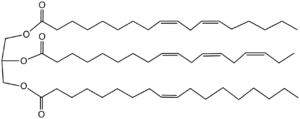

Traditional oil paints require an oil that always hardens, forming a stable, impermeable film. Such oils are called causative, or drying, oils, and are characterised by high levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids. One common measure of the causative property of oils is iodine number, the number of grams of iodine one hundred grams of oil can absorb. Oils with an iodine number greater than 130 are considered drying, those with an iodine number of 115–130 are semi-drying, and those with an iodine number of less than 115 are non-drying. Linseed oil, the most prevalent vehicle for artists' oil paints, is a drying oil.

When exposed to air, oils do not undergo the same evaporation process that water does. Instead, they dry semisolid. The rate of this process can be very slow, depending on the oil.

The advantage of the slow-drying quality of oil paint is that an artist can develop a painting gradually. Earlier media such as egg tempera dried quickly, which prevented the artist from making changes or corrections. With oil-based paints, revising was comparatively easy. The disadvantage is that a painting might take months or years to finish, which might disappoint an anxious patron. Oil paints blend well with each other, making subtle variations of color possible as well as creating many details of light and shadow. Oil paints can be diluted with turpentine or other thinning agents, which artists take advantage to paint in layers.

There is also another kind of oil paint that is water-mixable, making the cleaning and using process easier and less toxic.

Sources

.jpg.webp)

The earliest and still most commonly used vehicle is linseed oil, pressed from the seed of the flax plant. Modern processes use heat or steam to produce refined varieties of oil with fewer impurities, but many artists prefer cold-pressed oils.[8] Other vegetable oils such as hemp, poppy seed, walnut, sunflower, safflower, and soybean oils may be used as alternatives to linseed oil for a variety of reasons. For example, safflower and poppy oils are paler than linseed oil and allow for more vibrant whites straight from the tube.

Extraction methods and processing

Once the oil is extracted, additives are sometimes used to modify its chemical properties. In this way, the paint can be made to dry more quickly (if that is desired), or to have varying levels of gloss, like Liquin. Modern oils paints can, therefore, have complex chemical structures; for example, affecting resistance to UV. By hand, the process involves first mixing the paint pigment with the linseed oil to a crumbly mass on a glass or marble slab. Then, a small amount at a time is ground between the slab and a glass Muller (a round, flat-bottomed glass instrument with a hand grip). Pigment and oil are ground together 'with patience' until a smooth, ultra-fine paste is achieved. This paste is then placed into jars or metal paint tubes and labelled.

Pigment

The color of oil paint is derived from small particles of colored pigments mixed with the carrier, the oil. Common pigment types include mineral salts such as white oxides: zinc oxide, titanium dioxide, and the red to yellow cadmium pigments. Another class consists of earth types, the main ones being ochre, sienna and umber. Still another group of pigments comes from living organisms, such as madder root. Synthetic organic pigments are also now available. Natural pigments have the advantage of being well understood through centuries of use, but synthetics have greatly increased the spectrum of available colors, and many have attained a high level of lightfastness.

When oil paint was first introduced in the arts, basically the same limited range of available pigments were used that had already been applied in tempera: yellow ochre, umber, lead-tin-yellow, vermilion, kermes, azurite, ultramarine, verdigris, lamp black and lead white. These pigments strongly varied in price, transparency and lightfastness. They included both anorganic and organic substances, the latter often being far less permanent. The painter bought them from specialised traders, "colour men", and let his apprentices grind them with oil in his studio to obtain paint of the desired viscosity.

During the Age of discovery, new pigments became known in Europe, mostly of the organic and earthy type, such as Indian yellow. In the eighteenth century, the developing science of chemistry deliberately tried to expand the range of pigments, which led to the discovery of Prussian blue and cobalt blue.

Toxicity

Many of the historical pigments were dangerous, and many pigments still in use are highly toxic. Some of the most poisonous pigments, such as Paris green (copper(II) acetoarsenite) and orpiment (arsenic sulfide), have fallen from use.

Many pigments are toxic to some degree. Commonly used reds and yellows are produced using cadmium, and vermilion red uses natural or synthetic mercuric sulfide or cinnabar. Flake white and Cremnitz white are made with basic lead carbonate. Some intense blue colors, including cobalt blue and cerulean blue, are made with cobalt compounds. Some varieties of cobalt violet are made with cobalt arsenate.

See also

External links

- Business Insider, July 13, 2019 "Why Oil Paint Is So Expensive?" 6 minute YouTube video

References

- Mayer, Ralph. The Artist's Handbook of Materials and Techniques Viking Adult; 5th revised and updated edition, 1991. ISBN 0-670-83701-6

- Gottsegen, Mark David. The Painter's Handbook Watson-Guptill; Revised and expanded, 2006 ISBN 978-0-8230-3496-3

- Coremans, Gettens, Thissen, La technique des Primitifs flamands, Studies in Conservation 1 (1952)

- https://artcritical.com/2018/07/13/david-carrier-on-chaim-soutine/

- "Oldest Oil Paintings Found in Afghanistan" Archived June 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Rosella Lorenzi, Discovery News. Feb. 19, 2008.

- Theophilus Presbyter Book I ch. 25

- Barbera, Giocchino (2005). Antonello da Messina, Sicily's Renaissance Master (exhibition catalogue). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-11648-9 (online), p. 14

- Hurt, Perry. "Never Underestimate the Power of a Paint Tube". Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- Callen, Anthea. The Art of Impressionsm: How Impressionism Changed the Art World. Yale University Press. 2000.

- H. Gluck, "The Impermanences of Painting in Relation to Artists' Materials", Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, Volume CXII 1964