Bellamy Mansion

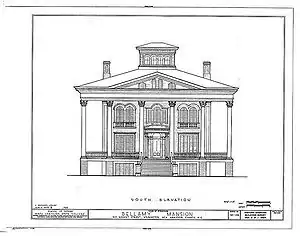

The Bellamy Mansion, built between 1859 and 1861, is a mixture of Neoclassical architectural styles, including Greek Revival and Italianate, and is located at 503 Market Street in the heart of downtown Wilmington, North Carolina. It is one of North Carolina’s finest examples of historic antebellum architecture. It is a contributing building in the Wilmington Historic District.

Background

In 1860, Wilmington was the largest city in North Carolina by population and was number one in the world for the naval stores industry. It was considered a cosmopolitan port city where men like Dr. John D. Bellamy could advance themselves politically, economically and culturally. Designed with Greek Revival and Italianate styling, this twenty-two room house was constructed with the labor of both enslaved skilled carpenters and freed black artisans. In 1860 this was a construction site. The architect James F. Post, a native of New Jersey, and his assistant, draftsman Rufus W. Bunnell of Connecticut, oversaw the construction of the mansion.[1] Originally built as a private residence for the family of |Dr. John D. Bellamy, a prominent plantation owner, physician, and businessman, the mansion has endured a remarkable series of events throughout its existence. Mrs. Bellamy’s formal gardens were not planted until closer to 1870, and when the mansion was first built there were no large shade trees like today. By the time Dr. Bellamy and Eliza Bellamy moved into the house in early 1861, they had been married twenty years and moved in with eight children who ranged in age from a young adult all the way to a toddler. In fact, Eliza was pregnant with her tenth child. Ten Bellamys moved into the big house while nine enslaved workers moved into the outbuildings. The home was taken over by federal troops during the American Civil War, survived a disastrous fire in 1972, was home to two generations of Bellamy family members, and now following extensive restoration and preservation over several decades, the Bellamy Mansion is a fully functioning museum of history and design arts.

It is now a stewardship property of Preservation North Carolina, a private nonprofit organization dedicated to the protection of historic sites in North Carolina.[1]

Family

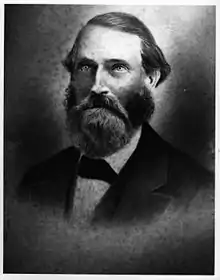

John Dillard Bellamy, M.D. (September 18, 1817 - August 30, 1896) married Eliza McIlhenny Harriss (August 6, 1821 – October 18, 1907) on June 12, 1839. Over the next twenty-two years Dr. and Mrs. Bellamy welcomed ten children to their family: Mary Elizabeth (Belle) (1840–1900) would be the first, followed by Marsden (1843–1909), William James Harriss (1844–1911), Eliza (Liza) (1845–1929), Ellen Douglass (1852–1946), John Dillard Jr. (1854–1942), George Harriss (1856–1924), Kate Taylor (1858-1858), Chesley Calhoun (1859–1881), and Robert Rankin (1861–1926).[2]

As a young man, John Dillard Bellamy, Sr. inherited a large piece of his father’s plantation in Horry County, South Carolina at about age 18, along with several enslaved workers. John soon moved to Wilmington, North Carolina, to begin studying medicine with Dr. William James Harriss. He left for two years in 1837 to study at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and he returned to Wilmington in 1839 to marry Eliza, Harriss' eldest daughter and take over Dr. Harriss’ medical practice following Eliza’s father’s untimely death in July. After their wedding, Bellamy took over Dr. William James Harriss' medical practice in July 1839. The Bellamys lived in the Dock Street home of Eliza’s newly widowed mother, Mary Priscilla Jennings Harriss. Upon his death, Dr. Harriss left behind his wife, along with seven children and fourteen enslaved workers who were also living at the household. John and Eliza welcomed four of their own children into the Dock Street home before they moved across the street in 1846 to the former residence of the sixteenth Governor Benjamin Smith. It was here, from 1852-1859, that the next five of the Bellamy’s ten children were born.[1]

By 1860, as the Bellamy family prepared to move into their new home on Market Street, their family included eight children, ages ranging from one to nineteen. Along with the ten members of the Bellamy family, nine enslaved workers also lived at the household. In 1861, Robert Rankin was the last born of the children and the only one to be born in the mansion on Market Street.[1]

Dr. Bellamy’s prosperity continued to grow through the second half of the nineteenth century and by 1850 he was listed as a "merchant" on the census. His medical practice was successful; however, the majority of his wealth came from his operation of a turpentine distillery in Brunswick County, his position as a director of the Bank of the Cape Fear, and his investment, as director and stockholder, in the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad. Grovely Plantation was "an almost ten thousand acre" produce plantation on Town Creek in Brunswick County, now a present-day Brunswick Forest development, on which Dr. Bellamy raised livestock and crops such as "wheat, oats, corn, and peanuts." In 1860, he had 82 enslaved workers living in 17 "slave cabins" at Grovely, while the family lived in a "comfortable and pleasant" home that was "no stately mansion." Grist Plantation was a turpentine plantation in Columbus County, near Chadbourn, North Carolina. Dr. Bellamy kept 24 enslaved men between the ages of 18-40 living in 9 slave cabins. The work was extremely difficult for the enslaved workers but very profitable for Dr. Bellamy. According to John D. Bellamy, Jr. his father told him concerning the home at 5th and Market the "amount of its cost was only one year's profit that he made at Grist." Dr. Bellamy was an extremely wealthy man as indicated by his land and slave holdings. In 1860, he owned 114 enslaved workers in North Carolina spread across three counties. Only 117 other men in the entire state owned between 100-199 enslaved workers out of a slave owning population of almost 35,000, meaning John D. Bellamy was in the upper echelon and of the planter class.

The sons of Dr. John D. Bellamy followed in their father’s footsteps and became successful students and career men in and outside of Wilmington. Marsden, the eldest of the sons, became a prominent trial attorney in Wilmington. William developed a successful medical practice of his own, just as his father and grandfather had before in Wilmington. George became a farmer and took over Grovely Plantation, land that his father had purchased in 1842 in Brunswick County, North Carolina, later going on to serve multiple terms in the North Carolina Senate between 1893 and 1914. The youngest son, Robert, became a successful businessman in the pharmaceutical industry. John Jr. attended Davidson College, and the University of Virginia Law School, and eventually became a successful politician in the conservative Democratic Party. From 1899 -1903 John Jr. represented North Carolina as a United States Congressman, and served as the Dean of the North Carolina Bar Association from 1926-1927. Chesley Calhoun unfortunately died at the young age of twenty-one, while studying at Davidson College.[1]

Only one of the four daughters of Dr. and Mrs. John D. Bellamy grew to marry and have children. Mary Elizabeth (Belle) married William Jefferson Duffie of Columbia, South Carolina on September 12, 1876. They had two children, Eliza (Elise) Bellamy Duffie, and Ellen Douglas Duffie. Of the other three daughters of Dr. and Mrs. Bellamy, Eliza and Ellen lived out their days unmarried in the family mansion on Market Street, while Kate Taylor died as an infant in 1858. Later in life Ellen would write her memoir Back With the Tide, which provides an informative inside account of the Bellamy Mansion and its history.

In March 1861 the family prepared to move into their new home on Market Street, and held a housewarming party, as well as the celebration of two cousins' weddings. The dining room table here was "laden with everything conceivably good," but the Civil War broke out the following month and "ended all entertaining for four long years."

Two months after moving into the new home, on May 20, 1861, North Carolina officially seceded from the Union. Dr. Bellamy was a secessionist, and he assumed the honor of heading the welcoming committee when Jefferson Davis visited Wilmington in late May.[1] John Jr. described his father as an "ardent Secessionist, Calhoun Democrat, and never after the war ‘reconstructed.’" Dr. Bellamy was so proud of South Carolina’s secession in December 1860 and so dismayed that many prominent Wilmington families "would not take part in the celebration of South Carolina's withdrawal from the Union, he bought all the empty tar barrels in Wilmington and had them strewn along Front Street...and had a great bonfire and procession at night, three days before the Christmas of 1860. He procured a band of music, and headed the marching column himself, at Front and Market Streets, with his little son and namesake, the author, by his side, bearing a torch upon his shoulder! It was a night to live always in his memory, and of which he was ever afterwards proud!" Marsden Bellamy, the eldest of the sons, had enlisted in the Scotland Neck Cavalry volunteers before the official secession, and later enlisted in the Confederate Navy. Just a few months later, his younger brother William would join the Wilmington Rifle Guards.

When the family returned, Mary Elizabeth and Eliza moved back in with their parents. Ellen was 13 years old with four younger brothers growing up in the house. Three of the brothers are pictured in portraits. John Jr. was about 10 years old when they returned. He grew up to become a politician, lawyer, and U.S. Congressman. (portrait above fireplace. Chesley was almost 6 years old. Chesley went off to Davidson College, caught a virus, and came home to die before his 21st birthday. (portrait by rocking chair). Robert was the only Bellamy born in this house, and when they moved back in he was about 4 years old. He went on to become a successful Davidson-college educated merchant and pharmacist in town. (portrait over sofa). George, the only one not pictured in the family parlor, was 8 when they moved back in 1865. He went on to become a farmer and ran Grovely Plantation for his father when he grew up.

Paid and Enslaved Workers

Ten Bellamys moved into the big house while nine enslaved workers moved into the outbuildings. Guy Nixon, the butler and carriage driver for the Bellamys, would run errands, answer the door, and serve meals. Tony Bellamy, the caretaker, most likely conducted maintenance and grounds keeping on the property. The fact he took Dr. Bellamy’s last name after emancipation most likely means he lived primarily at Grovely and only came to town when needed. If the needed repairs and work required him to stay in Wilmington overnight or longer, he would have most likely slept in the same area as Guy. Sarah Miller Sampson (1815-1896) belonged to Dr. William Harriss, Dr. John D. Bellamy’s father-in-law, and was given to Eliza and John D. Bellamy in 1839, the year of their marriage and of Dr. Harriss’s untimely death just a few weeks after the ceremony. Rosella and six other females were also working in the home, including Joan, a wet nurse and nanny for the Bellamy children; Caroline, Joan’s daughter (who was 7 in 1860) and was described as Mrs. Bellamy’s "little maid" who followed Eliza "from foot to foot"; Mary Ann, a 14-year old in 1860 who was likely learning tasks from Sarah, Joan, and Rosella. A 4-year-old girl, a 3-year-old girl and a 1-year-old girl were also listed on the census.

The enslaved craftsmen, such as brick masons, carpenters, and plasterers, were hired by Dr. Bellamy in what was known as the "hiring out" system whereby enslaved workers would congregate at the Market House near New Year’s Day and wealthy men would engage them in temporal contracts, usually in construction. Rufus Bunnell noted on January 2, 1860 that "Hundreds of (N)egro slaves huddled about the Market House … sitting or standing in the keen weather" to renew their contracts.

Even those who had constructed the Bellamy Mansion would join in the war effort on both sides of the Mason–Dixon line. The architect, James F. Post had joined the Confederate artillery, and even helped to build various structures at Fort Fisher and Fort Anderson. As he had since returned to the north after his duties were completed, draftsman Rufus W. Bunnell had joined the Connecticut regiment of the Union Army.[1]

William B. Gould, a mulatto, was owned by the Nixon family and was a plasterer who was hired out by Dr. Bellamy. The enslaved plasterer managed to escape from Wilmington with several other enslaved workers on the night of September 21, 1862. Eight enslaved workers rowed a small boat down the Cape Fear River to a Union blockade ship, where Gould and some of the others joined the Union navy. Despite it being illegal to teach slaves to read and/or write in North Carolina by 1830, Gould had kept an extensive diary during the war, which is thought to be one of only a few diaries written by a former slave serving in the Civil War in existence today. Gould later continued plastering in Massachusetts, where he married and had eight children.[1] In the 1990s his great-grandson, William B. Gould IV, edited Gould’s diary into a book titled, Diary of a Contraband: The Civil War Passage of a Black Sailor.

After the family settled back into their home and Dr. Bellamy restarted production at Grovely, he was, of course, using paid labor. Of the enslaved workers who had resided here before the Civil War only one remained as a paid servant. Mary Ann Nixon was still working for the Bellamys in 1870 and still living in the slave quarters with one other "domestic servant." Sarah seemingly retired and by 1866 was living on Red Cross St. with her husband, Aaron Sampson. Sarah and Aaron were married when Sarah was just 15 years old, but they did not live together until she was about 50 years old. She was listed on the 1870 census as "keeping house." Aaron was an enslaved carpenter who continued as a carpenter in Wilmington after emancipation.

History

As the war continued, the Bellamys remained in residence at their new Market Street home. However, the deadly outbreak of a yellow fever epidemic had begun to spread throughout Wilmington and the family was forced to take refuge at Grovely Plantation. On January 15, 1865 Dr. Bellamy and his family learned that Fort Fisher had fallen to the federal troops under General Alfred H. Terry. This was a devastating blow to the Confederacy, as Wilmington was the last major port supplying the southern states.[1]

While the family was still at Grovely Plantation, Federal troops arrived in Wilmington on February 22, having pushed many of the Confederate troops inland. Union officers took shelter in the nicer homes in town whose owners had been forced to abandon them. The Bellamy House was quickly occupied and chosen to be headquarters for the military staff. On March 1, 1865 General Joseph Roswell Hawley was placed in charge of the Wilmington District and assigned the Bellamy House. Soon after, the General’s wife Harriet Foote Hawley, an experienced war nurse, arrived in Wilmington in April 1865 to help tend to the wounded.[1]

After the official end of the war in April 1865, the Federal Government seized southern property, including land, buildings, and homes of Dr. Bellamy. The Bellamys came to reclaim their house, but Dr. Bellamy was not allowed into Wilmington, courtesy of General Hawley — Dr. Bellamy's reputation preceded him. Gen. Joseph Hawley wrote about Dr. Bellamy to another Union officer upon receipt of Dr. Bellamy’s oath of allegiance to the federal government stating, "As a specimen of the temper of certain people I inclose a copy of an application from J.D. Bellamy, which explains itself. Bellamy was a rabid secessionist here and tyrannized over all suspected of Unionism. He ran away, but only to get under the feet of General Sherman’s forces. From a neighboring county he sends in this appeal. I have answered verbally that having for four years been making his bed, he now must lie on it for awhile. I have no time to take him within the lines."

Mrs. Bellamy had traveled into Wilmington in May 1865 to meet with Mrs. Harriett Foote Hawley hoping to retrieve her home. It is assumed that it wasn't easy for Eliza Bellamy to be entertained by a "yankee" in her own home, but it has been reported that she behaved as a proper Southern lady, and acted with politeness. Ellen describes her mother as having intentions of regaining their home, but the meeting did not go as planned. Eliza and Harriett were very different with one major difference being Eliza was a pro-slavery Confederate while Harriett was from a staunch Hartford, Connecticut abolitionist family. In fact, Harriett was a first cousin of Harriet Beecher Stowe who wrote the abolitionist work Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Eliza recalled Harriett spit tobacco into the fireplace. Eliza was also upset that Harriett offered her "some figs...which Aunt Sarah had picked." Sarah served the Union officers and was most likely paid for service. General and Mrs. Hawley left for Richmond, Virginia soon after, however the home was still being occupied by other Union soldiers.[1]

Dr. Bellamy's home retrieval process was lengthy, likely because of his political views and his former status as a large slaveholder. In the summer of 1865, he sought a pardon to reclaim his property. By August 21, he received a Presidential Pardon from Andrew Johnson to retrieve his plantation land and commercial buildings, but the Bellamy House on Market Street was still under military control. Eliza wrote Belle "the Mirrors, Mantles, & gas fixtures are very little abused" but the "walls, paint, & floors shamefully" dirty. She even described the basement as "more like hog pen than anything else." By the end of September 1865, the Bellamy family sought to return to their home in Wilmington.[1]

Dr. Bellamy finally obtained his property, but he now had to hire freed workers for the turpentine distillery, Grovely Plantation, and the family home on Market Street. He resumed his practice of medicine to gain the extra money needed to pay off debts brought about by the building of the mansion, the war, and military occupation. In the early 1870s as the children grew older, Mrs. Bellamy along with her daughter Ellen, made plans to surround the property of the home with a beautiful black iron fence, which would enclose a picturesque garden to be laid out by Mrs. Bellamy herself. She could now pursue her hobby of horticulture. This fence and the garden have been maintained throughout the years and remain on the grounds of the mansion today.[1]

Throughout the rest of the nineteenth century, the children of Dr. and Mrs. Bellamy would go on to live their lives as successful businessmen, farmers, politicians, doctors, homemakers, fathers and mothers. Dr. Bellamy died just before the turn of the century in 1896, and his wife Eliza passed away roughly ten years later in 1907. Eliza and Ellen, the daughters of Dr. and Mrs. Bellamy lived the rest of their days in the mansion, Eliza passing on in 1929 and Ellen in 1946.

Architecture

Design and construction

It is unclear where the idea for such an elaborate structure with a full colonnade came from, but certain signs point to the artistic eye of Belle, the first Bellamy child.[1] While studying in South Carolina, she had taken a liking to a nearby home in Columbia that featured a similar design, and so she shared her ideas with Dr. Bellamy and eventually with the draftsman, Rufus W. Bunnell. Dr. Bellamy hired James F. Post, an architect in Wilmington who had been the supervisor of the construction of Thalian Hall, designed by the renowned John M. Trimble. In May 1859, Post hired Bunnell to be an assistant architect. Henry Taylor was another carpenter who worked on the house. Born to a white man who was also his master, he was known to be nominally an enslaved man, but treated as free.[3] Drawings for Dr. Bellamy’s new home would be produced through the late summer and early fall months, and in October the excavation of the construction site began and the foundation was laid.[1]

After the New Year most of Bunnell’s drawings were complete and most of the building supplies had been ordered from New York, including the large Corinthian columns, along with various blinds and window drapings. By February a large portion of the pine frame had been erected, and in March the cornices and the tin roof on the mansion were completed. Slave quarters and a small carriage house, both made of red brick, were also on the property. Among the men building the house were a number of enslaved workers from Wilmington, several freed black artisans, and other skilled carpenters from the area. William B. Gould and other enslaved workers and artisans exhibited their fine skills in the plaster moldings of the interior of the main house and extensive woodwork throughout all twenty-two rooms of the home. The mansion began to take the form of Bunnell and Post’s ultimate vision.[1]

Although Dr. Bellamy wanted his home constructed with classic style, and in an old reliable fashion, he was very much interested in modern utilities and innovations that would allow his family to live in comfort. The house was equipped with running hot and cold water, which was supplied by a large cistern and pump. The mansion was even furnished with gas chandeliers to light the large rooms. The channeled tin roof allows for quick and effective drainage, and insulation; due to Wilmington’s high heat and humidity levels in the summer months Dr. Bellamy also wanted the large, door-sized windows of the first floor to open all the way, disappearing into the wall. This allowed for cross breezes to circulate through both the home and multiple walkways to and from the wraparound porch.

Because the children’s rooms on the top floor did not have these large windows, another way to ventilate their living space was needed. Each of the small bedrooms on the top floor had vents that traveled up and emptied into the belvedere at the very top of the mansion. On hot days, the windows of the belvedere were propped open to create a vacuum effect to naturally cool the upper floors of the home. Besides the various modern features, the home was also outfitted with luxurious wood, iron and metal works, along with lavish rugs, furniture, and other forms of décor. Although Dr. Bellamy was described as a man with somewhat conservative taste, he needed his home to be both modern and comforting, accommodating to the large number of people living in it.

Slave Quarters

The now restored slave quarters on the property are one of the best examples of urban quarters in the state, and one of very few open to the public. Seven enslaved female African Americans lived in this building including Sarah, the housekeeper and cook, Mary Ann and Joan, nurses, Rosella, a nurse and laundress, and three children. Two enslaved men that lived on the Bellamy property included Guy, the butler and coachman, and Tony, a laborer and handyman. More than likely, they resided in small rooms above the carriage house. The architecture of the slave quarters is very distinct, and done very purposefully. The attractive brick walls and shutters were a sign of social superiority for the Bellamy family. Because these were urban quarters, they could easily be seen by the public from street level. Having a visibly pleasing slave quarter gave the impression of high social status for the family. There are no windows on the rear of the slave quarters, meaning enslaved workers could only look out and view the main house, which they were close to. High walls, sometimes more than a foot thick, surrounded the entire property, forming a compound where workers spent their day. The smallness of the yards and gardens at the center of the lots seem to magnify the commanding size of the walls and emphasize the calculated isolation of the quarters. The relentless masonry was broken only by the stark escarpment created by the rear of the adjacent buildings- the backs of kitchens, stables, or neighboring slave quarters. Standing in the middle of the plot, the enslaved worker could see only a maze of brick and stone. Thus, the physical design of the complex directed enslaved workers to center their activity upon the owner and the owner's house. Symbolically, the pitch of the roof of the slave quarters was highest at the outside edge and then slanted sharply toward the yard; an expression of the human relationship involved. The whole design was concentric, drawing the life of the slaves inward. After the Civil War, this building became servants' quarters.

Restoration

In February 1972 fourth generation members of the Bellamy family started Bellamy Mansion, Inc., in hopes of beginning preservation and restoration of the historic home. Sadly, one month later arsonists set fire to the home. While the fire department was able to put out the flames, extensive damage was done to a large amount of the interior.[1]

After the devastating fire in March 1972, Bellamy Mansion, Inc. faced a whole new set of challenges regarding the restoration of the home. The house had sustained extensive damage to its plaster work and much of the original wood had been destroyed. Further damage came from the water needed to extinguish the blaze. Over the next two decades more Bellamy family members and community volunteers joined to raise awareness and funds for the restoration effort.[1]

Through the 1970s and 1980s, Bellamy Mansion, Inc., worked to complete exterior restoration of the main home and the servants' quarters in the rear of the property, and to raise funds for the interior renovations. In 1989, the corporation decided to donate the property to the Historic Preservation Foundation of North Carolina. This turned the mansion into a public historic site. Over the next few years the necessary interior repairs were completed, and in 1994 the Bellamy Mansion Museum of History and Design Arts officially opened.[1]

Today the Bellamy Mansion is a fully operational museum, focusing on history and design arts, and a Stewardship Property of Preservation North Carolina.[4] The facility often features changing exhibits of history and design as well as various community events, including the annual garden tour of the famous North Carolina Azalea Festival in Wilmington. In 2001 the carriage house at the rear of the property was reconstructed and became the museum’s visitor center and office building. The authentic and unique slave quarters, fully restored as of 2014, serves to depict the conditions in which enslaved workers lived. Because the property's slave quarters were constructed only a few years before the abolition of slavery, they are some of the best preserved examples of urban slave housing in the country.

Acting as a nonprofit organization, the Bellamy Mansion is home to many volunteers from the Wilmington community who are knowledgeable of the Bellamy family and the history of the home itself. Tours are given at the museum Tuesday – Saturday from 10:00 AM – 5:00 PM (with the last tour starting at 4:00 PM) and Sunday from 1:00 PM – 5:00 PM (with the last tour starting at 4:00 PM). Aside from being an operational museum, the Bellamy Mansion is also available for weddings and special events rentals. The structure is located at 503 Market Street in Wilmington and on the Web at www.bellamymansion.org [4]

Sources

- Bisher, Catherine W. The Bellamy Mansion Wilmington North Carolina: An Antebellum Architectural Treasure and Its People 2004 PNC Inc.

- Cashman, Diane Cobb. History of The Bellamy Mansion. January 1990.

- Bishir, Catherine W. The Bellamy Mansion: An Antebellum Architectural Treasure and Its People. Raleigh: Historic Preservation Foundation of North Carolina, Inc, 2004.

- "Bellamy Mansion Museum". Bellamy Mansion Museum. Retrieved July 24, 2019.