Building restoration

Building Restoration describes a particular treatment approach and philosophy within the field of architectural conservation and historic preservation. It emphasizes the preservation of structures such as historic sites, houses, monuments, and other significant properties through careful maintenance and upkeep. Restoration aims to create accurate depictions of these locations and protect them against deterioration that could make them inaccessible or unrecognizable in the future.

Overview

In the field of historic preservation, building restoration is the action or process of accurately revealing, recovering or representing the state of a historic building, as it appeared at a particular period in its history, while protecting its heritage value. Restoration work may be performed to reverse decay, or alterations made to the buildings.

Since Historic Building Conservation is more about fostering a deep appreciation for these famous structures and learning more about why they exist, rather than just keeping historic structures standing tall and looking as beautiful as ever, true historic building preservation aims for a high level of authenticity, accurately replicating historic materials and techniques as much as possible, ideally using modern techniques only in a concealed manner where they will not compromise the historic character of the structure's appearance.[1]

For instance a restoration might involve the replacement of outdated heating and cooling systems with newer ones, or the installation of climate controls that never existed at the time of building after careful study. Tsarskoye Selo, the complex of former royal palaces outside St Petersburg in Russia is an example of this sort of work.

Exterior and interior paint colors present similar problems over time. Air pollution, acid rain, and sun take a toll, and often many layers of different paint exist. Historic paint analysis of old paint layers now allow a corresponding chemical recipe and color to be re-produced. But this is often only a beginning as many of the original materials are either unstable or in many cases environmentally unsound. Many eighteenth century greens were made with arsenic and lead, materials no longer allowed in paints. Another problem occurs when the original pigment came from a material no longer available. For example, in the early to mid-19th century, some browns were produced from bits of ground mummies. In cases like this the standards allow other materials with similar appearance to be used and organizations like Britain's National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty will work with a historic paint color re-creator s to replicate the antique paints in durable, stable, and environmentally safe materials. In the United States the National Trust for Historic Preservation is a helpful resource. The polychrome painted interiors of the Vermont State House and Boston Public Library are examples of this type of heritage restoration.

Types of Treatment

Historical conservation is the "preservation and repair of archaeological, historical, and cultural sites and artifacts".[2] When dealing with building conservation, there are four primary types of treatment, or ways in which a property can be managed. Each one has their own objectives and limitations.

- Preservation "places a high premium on the retention of all historic fabric through conservation, maintenance and repair".[3] In other words, all the materials added to a building over its lifetime are retained and work is only completed when it is essential to prevent deterioration of the site.

The next two treatments are a subset of preservation with some variation to account for the different requirements of the building and the needs of the institution.

- Rehabilitation is a more lenient standard of preservation because it assumes the building is so deteriorated that it needs repair to prevent further damage. It focuses on maintaining the materials, features, and spatial relationships that give a building historic character and allows for additions or alterations to be made that do not destroy the integrity of the property.[4]

- Restoration like preservation, it works to maintain as much of the original material as possible. However, the focus of restoration is to present the property at a specific point in history. As result repairs and recreations of certain elements or fixtures are completed and anything which postdates the intended period is documented and removed. The extent of a restoration is limited by the existing structure or proof of pre-existing features that were previously modified. Designs that were never executed cannot be included.[5]

- Reconstruction the most substantial type of treatment, it allows for the recreation of a former sites, landscape, or objects that no longer exists using all new materials. It is limited to aspects of a historic building that are essential for understanding and must be completed on documentary and physical evidence. Unlike the other treatments, a reconstruction must be labeled as a "contemporary re-creation" as it has historical foundations but is new in construction.[6]

Why restore a building?

The reasons to restore a building most frequently fall into five main categories.[7]

Value - Buildings hold intrinsic value not only in the history of the building, how it was used, but also how it was built. Historic buildings, notably pre-WWII, are built with higher quality materials and built under different standards than modern buildings.

Architectural Design - Buildings have personalities, specific architectural elements that make the building unique and more valuable. Saving these unique traits within original building are ideal.

Sustainability - Restoring a building for another purpose than its original intent is called adaptive reuse. Financially, businesses are better off restoring a building and adapting it for modern use than constructing a new site. The buildings are often built to better standards and as mentioned above have unique architectural elements that can increase business.

Cultural Significance - One of the most important reasons that a site is restored is because of its cultural significance. Certain sites are tied to a nation’s identity making the site more valuable for what it provides to the culture than if it were demolished. According to Building Talk, “the renovation of heritage buildings is essential to the permanent residence of history and culture in the nation’s psyche.”[8]

One Chance Rule - When a building is demolished what is lost cannot be measured. The site could hold a one of a kind design element or a historically significant past currently unknown. The One Chance Rule is guided by the idea that there is only one chance to restore a site and missing that opportunity could destroy a site of unknown significance.[9]

Although rare, there are times when a site would be demolished or reconstruction is chosen over restoration. This decision is made primarily when the resources to restore the site are unavailable. The challenge to reconstruction is that there is an element of conjecture in the process that can easily alter the site unintentionally.[10] Another reason not to restore a building is the value and knowledge that can be gained from the material remaining within the building. The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings has a unique approach to the preservation of historic buildings, which focuses on the materials that were used in the building's construction and what knowledge can be learned from the remaining material.[11]

Standards of Restoration

One of the biggest challenges to building restoration is that each country has their own terminology, standards, regulations and oversights which impact every restoration process. As a result, there are no international set of standards.[12] Conservators often follow best practices in the restoration approach. Every restoration project will adhere to the standard that the property is to be used as it was originally intended. This standard will guide all other decisions in the restoration process. This would include which materials are selected, to methods of construction, and finishing touches to the building such as fixtures. The property being restored is considered a record of its time. Any work undertaken will only be to restore the site to the specified time period and no removal of those historical elements will be made, however this does not exclude removing elements not historically accurate to the site.[13]

Best practices are as follows:

- Analysis of the site should be the first step in the restoration process. Conservators will need to examine the site to determine its status and what changes have previously been made and what work will need to be done going forward including removals. [14]

- Extensive documentation must be conducted. This includes taking an inventory of all objects and fixtures within the building. Photographing the building inside and outside is mandatory. Every element and feature of the building must be photographed and documented in writing such as their location and function. While this may seem to be excessive, this is a crucial step in understanding the site and what work will need completed.[15]

- Before any work on the site is done, a conservator will develop a collection management policy for the restoration. This policy will include a statement of purpose, a plan for the restoration including a list of all proposed changes to the site, a list of the current collection of the site, accessioning policies for new additions, deaccessioning policies for collection items that will be removed during the process, guidelines for the care of collection during the restoration process, and a section of ethical guidelines to follow as the restoration moves forward.[16] Additional sections can be added to the collection management policy depending on the building being restored, the items in the collection, and the historical significance of the site which could influence specific restoration requirements. One example of a collections management policy for restoration is the Edith Wharton Restoration, Inc. Collection Management Policy from The Mount, the historic home of Edith Wharton. The initial phase of restoration began in 1997, and has continually developed over the years.[17] The Collection Management Policy above is from 2004.

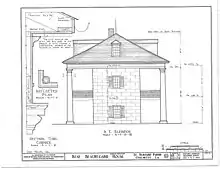

Exterior Restoration Plans for the Rene Beauregarde House, Chalmette, LA.

Exterior Restoration Plans for the Rene Beauregarde House, Chalmette, LA. - All materials from the selected restoration period will be preserved for restoration. This includes materials, architectural features, design elements such as paint or wallpaper associated with the restoration period. Materials and architectural elements not specific to that period will be removed during restoration.

- If a part of the building, fixtures, or design features are deteriorated, conservators must first attempt to repair the damage. If this is not possible, then a replacement is made. If replacement occurs, the new feature must match the original in color and design. Ideally, conservators will use materials associated with the time period, however this may not always be possible.[18]

- If a restoration requires an addition to the building, these changes must be proven through historical documentation and physical proof. Restoration avoids conjecture, and adding details that are not proven to have existed will only damage the value and significance of the site. If the building design did not exist in the period selected, it will not be included in the restoration.

- Any treatments undertaken during restoration efforts will follow best practices for the material being treated.[19] Treatments that will cause damage to the building or the historical materials within will not be used. Any treatment will affect the material, so conservators must carefully select the treatment method best for the material. For example, a brick facade will have a different treatment method from wrought iron.

Cultural Heritage Sites

Cultural Heritage is the physical and emotional reflection of a society, their legacy, and what they value. Tangible or physical representations include the material of the culture, locations of cultural significance, and the community associated with the culture. Intangible representations include oral stories, traditions, and the emotional connection to the cultural ancestors.[20] The conservation and restoration of cultural heritage sites pose different challenges and often follow different guidelines because of designation of a heritage site. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) is a guiding resource in the conservation of cultural heritage sites. UNESCO's mission is to identify, protect, and preserve World Heritage Sites. The World Heritage List is constantly evolving as new sites of cultural significance are added.[21] Another great resource for restoration of cultural heritage sites is the World Monuments Fund, which focuses on working with local groups around the world providing support for restoration, preservation, and stewardship.[22]

Restoration of Historic Buildings

Restoration of historic buildings varies from country to country, just as with cultural heritage sites and other building restoration projects. Before any work is done on a historic building, conservator-restorers should consult local requirements. Best practices listed above still apply. One example of restoration of historic buildings is the work conducted by the National Park Service which owns and maintains thousands of historic buildings and has been a leader in historic preservation for over 100 years. The standards were developed in 1975 and updated in 1992.[23] The standards deal with the "...materials, features, finishes, spaces, and spatial relationships..."[24] of historic buildings and are divided into preservation, rehabilitating, restoration and reconstruction.

Agents of Deterioration

As buildings can sustain various forms of damage and deterioration over time, understanding the cause of this damage and finding the best way to treat and prevent it is an important aspect to building restoration. The Agents of Deterioration are the ten primary sources of damage to heritage objects and buildings comprised in a comprehensive list by the Canadian Conservation Institute. The Agents are physical forces, fire, pests, light (ultraviolet and infrared), incorrect relative humidity, thieves and vandals, water, pollutants, incorrect temperature and the dissociation of objects.[25] While each of the ten agents can affect a historic building, some agents cause more common types of damage that may be addressed through building restoration.

- Fire damage can be a significant threat to historic buildings as many of the original components of these buildings may be made of wood or other flammable substances. Damage can result from internal fires such as electrical faults, external fires including forest fires and damage due to lightning strikes.[26] Fire damage can also increase the likelihood of water damage due to exposure to the elements, sprinkler systems and water used by safety personnel to put out the fire. Building restoration needed for this time of damage can include replacing wooden beams and structural elements as soon as possible to ensure that the building does not collapse, removing burnt flooring and plaster, and following a detailed plan of action to make sure that elements of the building are not lost during the restoration process.[27] Creating positive connections with local fire service personnel and establishing a fire safety plan can help to prevent or minimize future fire-related situations. An example of fire damage and restoration is the Notre-Dame de Paris fire that occurred on 15 April 2019. The fire caused significant damage to the roof and wooden structures including the destruction of the cathedral’s spire. The cause of the fire is still under investigation but may be due to an electrical shortage.[28] Reconstruction and restoration plans were approved on 16 July by the French parliament to recreate damaged structures in a way that preserves the historical and architectural integrity of their original construction.[29]

- Water damage, both interior and exterior, can cause significant damage to the structural integrity of a historic building and can create numerous types of damage that may need to be addressed during restoration. This can include burst pipes or flooding resulting in the peeling of paint from internal walls, the running of dyes from textiles and general staining.[30] Water damage also includes mold growth and internal deterioration due to incorrect humidity levels or a lack of humidity control within the building. It is recommended that wood, textiles and other absorbent materials that have sustained extensive water damage and cannot be dried and cleaned be removed and replaced, as they may continue to foster mold growth.[31] For historic buildings in areas that are prone to persistent flooding, the building can be raised or moved to a higher location. To mitigate general water control, an inspection checklist can be created for staff to inspect noticeable pipes, make note of any leaks within the building during storms as well as ensuring exterior elements of the historic building are adequately removing water such as drains and gutters. Internal humidity control devices can also mitigate mold and damage stemming from moisture. An example of water damage and building restoration is the extensive flooding of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice, Italy. While rising flood waters have been an increasing concern, a large flood on 12 November 2019 caused significant damage to the building, including damage to marble flooring, the deterioration of mosaics and mortar from salt in the water, and flooding of the crypt. Building restoration and prevention efforts include removing salt, checking for cracks in the flooring that may allow water to seep in and adding water pumps in the back of the building.[32] An emergency fund of €1m was implemented by the local government to aid in these efforts and further discussions of flood protection for the city are ongoing.[33]

- Pest control and awareness can prevent a variety of damage to historic buildings as well as preventing further damage in the future. Pests can include a variety of things from termites who can feast on the wooden structural elements of a historic building to rodents who may gnaw on or burrow into the building and objects within the building. Damage created by large pest infestations such as termites can be irreversible, with building restoration taking the form of replacement in order to maintain a sound structure for the building.[34] The most effective way to mitigate pest damage is to implement proactive measures prior to a pest infestation that may cause irreparable damage. These measures can include blocking off exterior openings, placing and checking traps for signs of pests and involving a pest management professional to check the building regularly.[35] An example of pest damage and control involving building restoration is the approach taken by Colonial Williamsburg. With over 600 historic buildings with wooden elements, Colonial Williamsburg has seen termite damage and has since created an extensive action plan in order prevent and detect termite activity. These measures include routine inspections, training staff in termite detection and performing restoration where needed.[36]

- Physical forces can impact a historic building in various ways both internally and externally. Powerful storms and winds can cause external damage to the building while internal forces such as strong impacts can cause cracks to walls or damage objects held within the building. Physical forces also include shocks and vibrations that can damage the fragile structure of the building, such as vibrations stemming from construction or large events.[37] Building restoration and damage prevention can include training staff on proper object handling within the space, performing evaluations on structural integrity and measuring the levels of vibration that are deemed safe in and around the building. Understanding the structural health of the building, including vibration measuring, can help in determining restoration work that is safe to perform. An example of physical forces that will require building restoration is damage to the historic Mechanics Hall building in Worcester, Massachusetts. Strong winds during a storm on 13 April 2020 caused portions of the copper roofing to be pulled from the building, allowing further damage to the attic and internal water damage.[38] With the cancellation of spring events due to COVID-19, restoration plans such as restoring the copper roof and fully repairing internal areas from water damage are pending. Recent research has found that self-healing coatings can be applied to rock and stone to repair cracks as they begin to appear; this technique has already been successfully applied at Tintern Abbey in Wales.[39]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Restoration of buildings. |

- Conservation-restoration

- Athens Charter

- Venice Charter

- Florence Charter

- Barcelona Charter

- Historic preservation

- International Union of Bricklayers and Allied Craftworkers

- Traditional trades

References

- Van Sanford, Scott. "Historic Building Restoration, Preservation, and Renovation". Pearl Bay Corporation. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- "Definition of Conservation". Oxford English Dictionary.

- Weeks, K (1996). "Historic Preservation Treatment Toward A Common Language". Cultural Resources Management. 19 (1): 32–35.

- Weeks, K (1996). "Historic Preservation Treatment Toward A Common Language". Cultural Resources Management. 19 (1): 32–35.

- Weeks, K (1996). "Historic Preservation Treatment Toward A Common Language". Cultural Resources Management. 19 (1): 32–35.

- Weeks, K (1996). "Historic Preservation Treatment Toward A Common Language". Cultural Resources Management. 19 (1): 32–35.

- Rocchi, J., & National Trust. (2015, November 10). Six Practical Reasons to Save Old Buildings: National Trust for Historic Preservation. Retrieved May 1, 2020, from https://savingplaces.org/stories/six-reasons-save-old-buildings?utm_medium=email&utm_source=NTHP_newsletter_062316&utm_campaign=NTHP_eNewsletter-FY16_June23_TEST#.Xq4GNxnYp6y

- 5 reasons we should restore historical buildings. (2017, February 24). Retrieved May 1, 2020, from https://www.buildingtalk.com/5-reasons-we-should-restore-historical-buildings/

- 5 reasons we should restore historical buildings. (2017, February 24). Retrieved May 1, 2020, from https://www.buildingtalk.com/5-reasons-we-should-restore-historical-buildings/

- Betz, K. W. (2017, November 6). Preserve, Rehab, Restore, Or Reconstruct? Retrieved May 2, 2020, from https://www.commarch.com/preserve-rehab-restore-reconstruct/

- Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. (2019, May 2). The SPAB Approach. Retrieved May 3, 2020, from https://www.spab.org.uk/campaigning/spab-approach

- Yates, T. (2019). British and European Standards for Heritage and Conservation. Retrieved May 1, 2020, from https://www.buildingconservation.com/articles/standards/standards.htm

- Restoration as a Treatment and Standards for Restoration-Technical Preservation Services, National Park Service. (n.d.). Retrieved May 1, 2020, from https://www.nps.gov/tps/standards/four-treatments/treatment-restoration.htm

- Canadian Conservation Institute (2018, August 30). Government of Canada. Retrieved May 1, 2020, from https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/risk-management-heritage-collections/abc-method-risk-management-approach.html

- White, M. (2016, December 6). 6 Tips to Document Historic Details Before They Disappear: National Trust for Historic Preservation. Retrieved May 1, 2020, from https://savingplaces.org/stories/6-tips-to-document-historic-details-before-they-disappear#.Xq5DChnYp6w

- American Alliance of Museums. (2012). Developing a Collections Management Policy. Alliance Reference Guide, 1–12.

- The Mount. (2020, April 9). The Estate: The Mount: Edith Wharton's Home. Retrieved May 3, 2020, from https://www.edithwharton.org/discover/the-estate/

- Concrete Renovations. (2019, July 28). Popular Techniques in Building Restoration. Retrieved May 3, 2020, from https://www.concreterenovations.co.uk/news/popular-techniques-in-building-restoration/

- Conservation-Restoration of Cultural Heritage. (n.d.). Conservation-Restoration of Cultural Heritage. Retrieved from https://rm.coe.int/strategy-21-conservation-restoration-of-cultural-hehttps://rm.coe.int/strategy-21-conservation-restoration-of-cultural-heritage-in-less-than/16807bfbbaritage-in-less-than/16807bfbba

- What is Cultural Heritage. (n.d.). Retrieved May 3, 2020, from http://www.cultureindevelopment.nl/Cultural_Heritage/What_is_Cultural_Heritage

- UNESCO (n.d.). World Heritage. Retrieved May 3, 2020, from https://whc.unesco.org/en/about/

- World Monuments Fund. (n.d.). Preservation & Beyond. Retrieved May 2, 2020, from https://www.wmf.org/what-we-do

- Jacobs, David E.. Guidelines for the evaluation and control of lead-based paint hazards in housing. Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 1995. 18-5. Print.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-11-22. Retrieved 2013-12-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Canadian Conservation Institute. “Agents of deterioration”, Government of Canada, 26 September 2017. Retrieved on 28 April 2020.

- "Restored chapel". Times of Malta. 26 April 2015. Archived from the original on 24 August 2015.

- Hutton, Tim. “After the Fire”, buildingconservation.com, 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- Richman-Abdou, Kelly. “Notre-Dame Updates: What We Know About the Cathedral Five Months After the Fire”, My Modern Met, 10 September 2019. Retrieved on 2 May 2020.

- Bandarin, Francesco. “New law regarding Notre Dame says restoration must preserve its 'historic, artistic and architectural interest’”, The Art Newspaper, 2 August 2019. Retrieved on 2 May 2020.

- Tremain, David. “Water”, Government of Canada, 17 May 2018. Retrieved on 28 April 2020.

- EPA. “Dealing with Debris and Damaged Buildings”, United States Environmental Protection Agency, 8 September 2017. Retrieved on 30 April 2020.

- Rodenigo, Veronica. “The cost of Venice's worst floods since 1966”, [The Art Newspaper]], 4 February 2020. Retrieved on 2 May 2020.

- Somers Cocks, Anna. “Governing body of St Mark’s basilica wants to build a Perspex anti-flood wall‘, [The Art Newspaper]], 3 January 2020. Retrieved on 2 May 2020.

- Jones, R., Silence, P. & Webster, M. “Preserving History: Subterranean Termite Prevention in Colonial Williamsburg”, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2013. Retrieved on 29 April 2020.

- Strang, T. & Kigawa, R. “Pests”, Government of Canada, 18 May 2018. Retrieved on 29 April 2020.

- Campbell, Emily. “Monitoring and Treating for Pesky Pests”, Colonial Williamsburg, 22 November 2019. Retrieved on 2 May 2020.

- Marcon, Paul. “Physical Forces”, Government of Canada, 17 May 2018. Retrieved on 29 April 2020.

- Croteau, Scott J. “Storm damages historic Mechanics Hall in Worcester as copper roof began to blow off, but it could have been worse”, MASSLIVE, 14 April 2020. Retrieved on 2 May 2020.

- Heingartner, Douglas (2021-01-20). "Nanotech for historic building preservation: bacterial coating lets historic buildings self-repair". PsychNewsDaily. Retrieved 2021-02-03.