Bill Griffith

William Henry Jackson Griffith (born January 20, 1944) is an American cartoonist who signs his work Bill Griffith and Griffy. He is best known for his surreal daily comic strip Zippy.[2] The catchphrase "Are we having fun yet?" is credited to Griffith.[3]

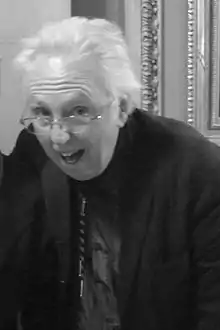

Bill Griffith | |

|---|---|

Bill Griffith, 25 March 2012 | |

| Born | William Henry Jackson Griffith January 20, 1944 |

| Other names | Griffy |

| Occupation | Cartoonist |

| Years active | 1969—present |

| Spouse(s) | Nancy Griffith (div. c. 1972) Diane Noomin |

| Awards | Inkpot Award (1992)[1] |

| Signature | |

| |

Early life, family and education

Born in Brooklyn, New York City, New York, Griffith grew up in Levittown, New York on Long Island. One of his neighbors was science fiction illustrator Ed Emshwiller, whom he credits with pointing him towards the world of art.[4] Griffith, his father and his mother all served as models for Emshwiller at one time or another; a very young Griffith appears (along with his father) on the cover of the September, 1957 issue of Science Fiction Stories.[5]

Career

Griffith began his comics career in New York City in 1969.[6] His first comic strips in the East Village Other and Screw featured an angry amphibian named Mr. The Toad.[2]

Underground comix

In 1969, Griffith began making underground comix.[2] He ventured to San Francisco, California in 1970[2] to join its burgeoning underground comix movement[6] and gained prominence in it, first with a hit comic Young Lust, "an X-rated parody of girl's romance comics."[7] and co-created with cartoonist Jay Kinney. Other early major comic book titles included Tales of Toad. He co-founded the comics anthology Arcade, the Comics Revue with Art Spiegelman and co-edited for its seven-issue run in the mid-1970s. Griffith has worked with the leading underground publishers throughout that decade and up to the present: Print Mint, Last Gasp, Rip Off Press, Kitchen Sink and Fantagraphics Books. He contributed comics and illustrations to a variety of publications, including National Lampoon, High Times, The New Yorker, The Village Voice and The New York Times.

Zippy

The first Zippy strip appeared in the underground Real Pulp #1 (Print Mint) in 1971. The strip went weekly in 1976, first in the Berkeley Barb and then syndicated nationally through Rip Off Press.[2] The one-row format Zippy strip debuted in the Berkeley Barb in 1976 and continues in weekly newspapers.

In 1979, he added his alter ego character, Griffy,[7] to the strip. He describes Griffy as "neurotic, self-righteous and opinionated, someone with whom Zippy would certainly contrast. I brought the two characters together around 1979, perhaps symbolically bringing together the two halves of my personality. It worked. Their relationship seemed to make Zippy's random nuttiness more directed and Griffy's cranky, critical persona had his foil, someone to bounce happily off of his constant analysis of everything and everyone around him."[8]

In 1986, the "Zippy Theme Song" was composed and performed, with lyrics by The B-52s' Fred Schneider and vocals by Manhattan Transfer's Janis Siegel.[9] Also on the cut are singers Phoebe Snow and Jon Hendricks.[10]

The daily Zippy strip (syndicated by King Features to over 200[2] newspapers worldwide) started in 1986. Griffith compares the creation of the strip to jazz: "When I'm doing a Zippy strip, I'm aware that I'm weaving elements together, almost improvising, as if I were all the instruments in a little jazz combo, then stepping back constantly to edit and fine-tune. Playing with language is what delights Zippy the most."[11]

In October 1994 Griffith toured Cuba for two weeks, during a period of mass exodus, as thousands of Cubans took advantage of President Fidel Castro's decision to permit emigration for a limited time. In early 1995, Griffith published a six-week series of "comics journalism" stories about Cuban culture and politics in Zippy. The Cuba series included transcripts of conversations Griffith had conducted with various Cubans, including artists, government officials, and a Yoruba priestess.[12]

Years ago, as continuity strips gave way to humor strips, typeset episode subtitles vanished from strips. In a nod toward the classic daily strips of yesteryear, Griffith keeps the tradition alive by always centering a hand-lettered subtitle above each Zippy strip.

In 2007, Griffith began to focus his daily strip on Zippy's "birthplace", Dingburg.[7] Griffith said, "Over the years, I began to expand Zippy's circle of friends beyond my usual cast of characters to a wider world of people like Zippy—other pinheads. I kept this up for a few months, happily adding more and more muu-muu-clad men and women until one day the whole thing just reached critical mass. The thought then occurred, 'Where do all these friends of Zippy live? Do they live in the real world which Zippy has been seen escaping for years—or do they live apart, in a pinhead world of their own?' Thus Dingburg, 'The City Inhabited Entirely by Pinheads' was born. It even had a motto: 'Going too far is half the pleasure of not getting anywhere'. The logical next step was to imagine Dingburg streets and neighborhoods—to create a place where Zippy's wacky rules would be the norm and everyone would play 24-hour Skeeball and worship at the feet of the giant Muffler Man. Zippy had, at last, found his home town."

In 2008, Griffith presented a talk on Zippy at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor. In it, he laid out his "Top 40 List on Comics and their Creation” which has been reposted on numerous comics blog posts and is available here in four illustrated parts: part 1, part 2, part 3 and part 4.

Other works

For a short period in the late 1960s, Griffith joined the team of artists, including Kim Deitch, Drew Friedman, Jay Lynch, Norman Saunders, Art Spiegelman, Bhob Stewart and Tom Sutton, who designed Wacky Packages trading cards for the Topps Company. Griffith recently drew Wacky Packages Old School Sketch Cards for Topps.

In 2015 Fantagraphics published Griffith's memoir Invisible Ink: My Mother’s Secret Love Affair With a Famous Cartoonist, and in 2019 his graphic biography of Schlitzie, Nobody's Fool: The Life and Times of Schlitzie the Pinhead was published by Harry N. Abrams.

Personal life

For over a decade, starting in 1957, Griffith's mother Barbara had an affair with cartoonist Lawrence Lariar; this formed the basis of Bill Griffith's 2015 graphic novel Invisible Ink: My Mother’s Secret Love Affair With a Famous Cartoonist.[13]

Invisible Ink depicts various other details and incidents involving Griffith's family, including the fact that Griffith himself is the great-grandson of the photographer and artist William Henry Jackson, and was named for him.

Griffith's first wife, Nancy, was also involved in the underground comix community.[14]

In 1998, Griffith and his second wife, cartoonist Diane Noomin,[2] moved from San Francisco to Connecticut.[12] His studio is in East Haddam, Connecticut.[6]

Bibliography

Zippy books and comics are published by Fantagraphics Books. In January 2012, Fantagraphics published Bill Griffith: Lost and Found, Comics 1969-2003, a 392-page collection of Griffith's early work in underground comics from the East Village Other to his pages for The New Yorker and the National Lampoon in the 1980s and 1990s.

Zippy titles (selected)

- Zippy Stories

- Nation of Pinheads

- Pointed Behavior

- Pindemonium

- Are We Having Fun Yet?

- Kingpin

- Pinhead's Progress

- Get Me a Table Without Flies, Harry (travel sketches)

- From A to Zippy

- Zippy's House of Fun

- Griffith Observatory

- Zippy Annual #1

- Zippy Annual 2001

- Zippy Annual 2002

- Zippy Annual 2003

- Zippy: From Here to Absurdity

- Zippy: Type Z Personality

- Zippy: Connect the Polka Dots

- Zippy: Walk a Mile in My Muu-Muu

- Zippy: Welcome to Dingburg

- Zippy: Ding Dong Daddy from Dingburg

References

- Inkpot Award

- "Bill Griffith". Lambiek.net. Lambiek Encyclopedia. July 10, 2016. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- "Are we having fun yet?". Bartlett's Familiar Quotations (16th ed.). 1992.

- "Bill Griffith". zippythepinhead.com.

- Post on Griffith's Facebook page; March 5, 2019

- Battista, Carolyn (July 11, 1999). "Q&A/Bill Griffith; Exploring The State With Zippy and Griffy". The New York Times.

- Heller, Steve (December 22, 2011). "Bill Griffith: The Man Who Made Zippy a Pinhead". The Atlantic. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- Dooley, Michael Patrick; Heller, Stephen (2005). The Education of a Comics Artist. Allworth Press. p. 43. ISBN 9781581154085.

- "Zippy Theme Song". zippythepinhead.com.

- Griffith, Bill (2012). Lost and Found: Comics 1969-2003. Fantagraphic Books. p. xxi. ISBN 978-1606994825.

- "Is he having fun yet?". zippythepinhead.com.

- "About Bill Griffith," Current Biography (2001). Archived at Zippy the Pinhead official Website. Accessed Dec. 11, 2019.

- “I Had Moments Where I Just Broke Down Crying”: An Interview with Bill Griffith, by Chris Mautner, in The Comics Journal; published November 23, 2015; retrieved December 16, 2015

- Fox, M. Steven. "Fits #2". ComixJoint.com. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

External links

- Radio interview relating to Griffith's book on the real "Zippy."

- Official Zippy The Pinhead site

- Dueben, Alex (October 6, 2008). "Is Bill Griffith Having Fun Yet?". ComicBookResources.com.

- "On the Road with Zippy the Pinhead" Boston Globe, 2011

- Review by novelist Paul Di Fillipo 2/12/12 in Barnes & Noble In The Margin blog

- Interview in Griffith's Connecticut studio in 2003 by the Hartford NBC-TV affiliate on YouTube

- Zippy Meets Mick Jagger