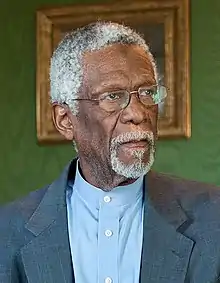

Bill Russell

William Felton Russell (born February 12, 1934) is an American former professional basketball player who played center for the Boston Celtics of the National Basketball Association (NBA) from 1956 to 1969. A five-time NBA Most Valuable Player and a 12-time All-Star, he was the centerpiece of the Celtics dynasty that won eleven NBA championships during his 13-year career. Russell and Henri Richard of the National Hockey League are tied for the record of the most championships won by an athlete in a North American sports league. Russell led the San Francisco Dons to two consecutive NCAA championships in 1955 and 1956, and he captained the gold-medal winning U.S. national basketball team at the 1956 Summer Olympics.[1]

Although Russell never averaged more than 19.0 points per game or shot as much as 47 percent in any season in an offense-friendly era, many regard him to be among the greatest basketball players of all time. He is 6 ft 10 in (2.08 m) tall, with a 7 ft 4 in (2.24 m) wingspan.[2][3] His shot-blocking and man-to-man defense were major reasons for the Celtics' domination of the NBA during his career. Russell was equally notable for his rebounding abilities. He led the NBA in rebounds four times, had a dozen consecutive seasons of 1,000 or more rebounds,[4] and remains second all-time in both total rebounds and rebounds per game. He is one of just two NBA players (the other being prominent rival Wilt Chamberlain) to have grabbed more than 50 rebounds in a game.

Russell played in the wake of black pioneers Earl Lloyd, Chuck Cooper, and Sweetwater Clifton, and he was the first black player to achieve superstar status in the NBA. He also served a three-season (1966–69) stint as player-coach for the Celtics, becoming the first black coach in North American professional sports and the first to win a championship. In 2011, Barack Obama awarded Russell the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his accomplishments on the court and in the Civil Rights Movement.[1]

He was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame and the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame. He was selected into the NBA 25th Anniversary Team in 1971 and the NBA 35th Anniversary Team in 1980, and named as one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History in 1996, one of only four players to receive all three honors. In 2007, he was enshrined in the FIBA Hall of Fame. In Russell's honor the NBA renamed the NBA Finals Most Valuable Player trophy in 2009: it is now the Bill Russell NBA Finals Most Valuable Player Award.

Early years

Family and personal life

Russell was born in 1934 to Charles Russell and Katie Russell in Monroe, Louisiana. Like almost all Southern towns and cities of that time, Monroe was very segregated, and the Russells often struggled with racism in their daily lives.[5] Russell's father was once refused service at a gas station until the staff had taken care of all the white customers first. When he attempted to leave and find a different station, the attendant stuck a shotgun in his face and threatened to kill him if he didn't stay and wait his turn.[5] In another incident, Russell's mother was walking outside in a fancy dress when a white policeman accosted her. He told her to go home and remove the dress, which he described as "white woman's clothing".[5] During World War II, large numbers of blacks were moving to the West to look for work there. When Russell was eight years old, his father moved the family out of Louisiana and settled in Oakland, California.[5] While there, they fell into poverty, and Russell spent his childhood living in a series of public housing projects.[5]

Charles Russell was described as a "stern, hard man" who initially worked in a paper factory as a janitor, which was a typical "Negro Job"—low paid and not intellectually challenging, as sports journalist John Taylor commented.[6] When World War II broke out, the elder Russell became a truck driver.[6] Russell was closer to his mother Katie than to his father,[6] and he received a major emotional blow when she suddenly died when he was 12 years old. His father gave up his trucking job and became a steelworker to be closer to his semi-orphaned children.[6] Russell has stated that his father became his childhood hero, later followed up by Minneapolis Lakers superstar George Mikan, whom he met when he was in high school.[7] Mikan, in turn, would say of Russell the college basketball player, "Let's face it, he's the best ever. He's so good, he scares you."[8]

Initial exposure to basketball

In his early years, Russell struggled to develop his skills as a basketball player. Although Russell was a good runner and jumper and had large hands,[6] he simply did not understand the game and was cut from the team in junior high school. As a freshman at McClymonds High School[9] in Oakland, Russell was almost cut again.[10] However, coach George Powles saw Russell's raw athletic potential and encouraged him to work on his fundamentals.[6] Since Russell's previous experiences with white authority figures were often negative, he was reassured to receive warm words from his coach. He worked hard and used the benefits of a growth spurt to become a decent basketball player, but it was not until his junior and senior years that he began to excel, winning back to back high school state championships.[10] Russell soon became noted for his unusual style of defense. He later recalled, "To play good defense ... it was told back then that you had to stay flatfooted at all times to react quickly. When I started to jump to make defensive plays and to block shots, I was initially corrected, but I stuck with it, and it paid off."[11] Russell, in an autobiographical account, notes while on a California High School All-Stars tour, he became obsessed with studying and memorizing other players' moves (e.g., footwork such as which foot they moved first on which play) as preparation for defending against them, which included practicing in front of a mirror at night. Russell further described himself as an avid reader of Dell Magazines' 1950s sports publications, which he used to scout opponents' moves for the purpose of defending against them.[12]

Future Baseball Hall-of-Famer Frank Robinson was one of Russell's high school basketball teammates.[13]

College years

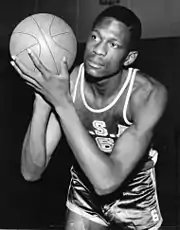

University of San Francisco

Russell was ignored by college recruiters and received not one offer until recruiter Hal DeJulio from the University of San Francisco (USF) watched him play in a high school game. DeJulio was unimpressed by Russell's meager scoring and "atrocious fundamentals",[14] but sensed that the young center had an extraordinary instinct for the game, especially in the clutch.[14] When DeJulio offered Russell a scholarship, he eagerly accepted.[10] Sports journalist John Taylor described it as a watershed event in Russell's life, because Russell realized that basketball was his chance to escape poverty and racism. As a consequence, Russell swore to make the best of it.[6]

At USF, Russell became the new starting center for coach Phil Woolpert. Woolpert emphasized defense and deliberate half-court play, which favored Russell's exceptional defensive skills.[15] Woolpert's choice of how to deploy his players was unaffected by their skin color. In 1954, he became the first coach of a major college basketball squad to start three black players: Russell, K. C. Jones and Hal Perry.[16] In his USF years, Russell took advantage of his relative lack of bulk to develop a unique defensive style: instead of purely guarding the opposing center, he used his quickness and speed to play help defense against opposing forwards and aggressively challenge their shots.[15] Combining the stature and shot-blocking skills of a center with the foot speed of a guard, Russell became the centerpiece of a USF team that soon became a force in college basketball. After USF kept Holy Cross star Tom Heinsohn scoreless in an entire half, Sports Illustrated wrote, "If [Russell] ever learns to hit the basket, they're going to have to rewrite the rules."[15][17] The NCAA did in fact rewrite rules in response to Russell's dominant play; the lane was widened for his junior year. After he graduated, the NCAA rules committee instituted a second new rule to counter the play of big men like Russell; basket interference was now prohibited.[18] The NCAA pays close attention to college basketball superstars. Over the years, other rule changes have been made to counter the dominant play of big men. Two examples are goaltending in response to George Mikan (1945) and prohibiting the dunk shot due to Lew Alcindor (1967), although the latter rule was later repealed.[19]

However, the games were often difficult for the USF squad. Russell and his black teammates became targets of racist jeers, particularly on the road.[20] In one incident, hotels in Oklahoma City refused to admit Russell and his black teammates while they were in town for the 1954 All-College Tournament. In protest, the whole team decided to camp out in a closed college dorm, which was later called an important bonding experience for the group.[16] Decades later, Russell explained that his experiences hardened him against abuse of all kinds. "I never permitted myself to be a victim", he said.[21][22]

Racism also shaped his lifelong paradigm as a team player. "At that time", he has said, "it was never acceptable that a black player was the best. That did not happen ... My junior year in college, I had what I thought was the one of the best college seasons ever. We won 28 out of 29 games. We won the National Championship. I was the [Most Valuable Player] at the Final Four. I was first team All American. I averaged over 20 points and over 20 rebounds, and I was the only guy in college blocking shots. So after the season was over, they had a Northern California banquet, and they picked another center as Player of the Year in Northern California. Well, that let me know that if I were to accept these as the final judges of my career I would die a bitter old man." So he made a conscious decision, he said, to put the team first and foremost, and not worry about individual achievements.[23]

On the hardwood, his experiences were far more pleasant. Russell led USF to NCAA championships in 1955 and 1956, including a string of 55 consecutive victories. He became known for his strong defense and shot-blocking skills, once denying 13 shots in a game. UCLA coach John Wooden called Russell "the greatest defensive man I've ever seen".[16] While at USF, together with K. C. Jones, he also helped pioneer a play that later became known as the alley-oop.[24][25] During his college career, Russell averaged 20.7 points per game and 20.3 rebounds per game.[1]

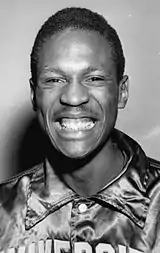

Track and field

Besides basketball, Russell represented USF in track and field events. Russell was a standout in the high jump, ranking the seventh-best high-jumper in the world in 1956 (his graduation year) according to Track & Field News (this despite not competing in Olympic high-jump competition that year[7]).[26] That year, Russell won high jump titles at the Central California AAU meet, the Pacific AAU meet, and the West Coast Relays. One of his highest jumps occurred at the West Coast Relays, where he achieved a mark of 6 feet 9 1⁄4 inches (2.06 m);[27] at the meet Russell tied Charlie Dumas, who would later in the year win gold in the Melbourne Olympics for the United States and become the first person to high-jump 7 feet (2.13 m).[28] Like fellow world-class high-jumpers of that era, Russell did not use the Fosbury Flop high-jump technique with which all high jump world records after 1978 have been set.[29][30]

Russell also competed in the 440 yards (402.3 m) race, which he could complete in 49.6 seconds.[31]

Professional basketball plans

The Harlem Globetrotters invited Russell to join their exhibition basketball squad. Russell, who was sensitive to any racial prejudice, was enraged by the fact that owner Abe Saperstein would only discuss the matter with Woolpert. While Saperstein spoke to Woolpert in a meeting, Globetrotters assistant coach Harry Hanna tried to entertain Russell with jokes. Russell, however, was livid after this snub and declined the offer. He reasoned that if Saperstein was too smart to speak with him, then he was too smart to play for Saperstein. Instead, Russell made himself eligible for the 1956 NBA draft.[32]

1956 NBA draft

In the 1956 NBA draft, Boston Celtics coach Red Auerbach set his sights on Russell, thinking his defensive toughness and rebounding prowess were the missing pieces the Celtics needed.[1] In retrospect, Auerbach's thoughts were unorthodox. In that period, centers and forwards were defined by their offensive output, and their ability to play defense was secondary.[33]

Boston's chances of getting Russell seemed slim, however. Because the Celtics had finished second in the previous season and the worst teams had the highest draft picks, the Celtics had slipped too low in the draft order to pick Russell. In addition, Auerbach had already used his territorial pick to acquire talented forward Tom Heinsohn.

Auerbach, however, knew that the Rochester Royals, who owned the first draft pick, already had a strong rebounder in Maurice Stokes, were looking for an outside shooting guard, and were unwilling to pay Russell the $25,000 signing bonus he requested. Celtics owner Walter A. Brown contacted Rochester owner Les Harrison, and received an assurance that the Royals could not afford Russell, and would instead draft Sihugo Green.[34] Auerbach later claimed that Brown offered Harrison guaranteed performances of the Ice Capades if they did not draft Russell; it is difficult to verify or disprove this, but it is clear that the Royals underrated Russell.[34]

The St. Louis Hawks, who owned the second pick, drafted Russell, but were vying for Celtics center Ed Macauley, a six-time All-Star who had roots in St. Louis. Auerbach agreed to trade Macauley, who had previously asked to be traded to St. Louis in order to be with his sick son, if the Hawks gave up Russell. The owner of St Louis called Auerbach later and demanded more in the trade. Not only did he want Macauley, who was the Celtics premier player at the time, he wanted Cliff Hagan, who had been serving in the military for three years and had not yet played for the Celtics. After much debate, Auerbach agreed to give up Hagan, and the Hawks made the trade.[35]

During that same draft, Boston also drafted guard K. C. Jones, Russell's former USF teammate. Thus, in one night, the Celtics managed to draft three future Hall of Famers: Russell, Jones and Heinsohn.[1] The Russell draft-day trade was later called one of the most important trades in the history of North American sports.[34]

1956 Olympics

Before his NBA rookie year, Russell was the captain of the U.S. national basketball team that competed at the 1956 Summer Olympics, which would be held in November and December in Melbourne, Australia in the Southern Hemisphere. Avery Brundage, head of the International Olympic Committee, argued that Russell had already signed a professional contract and thus was no longer an amateur, but Russell prevailed.[34] He had the option to skip the tournament and play a full season for the Celtics, but he was determined to play in the Olympics. He later commented that he would have participated in the high jump if he had been snubbed by the basketball team.[7] Under head coach Gerald Tucker, Russell helped the national team win the gold medal in Melbourne, by defeating the Soviet Union 89–55 in the final game. The United States dominated the tournament, winning by an average of 53.5 points per game. Russell led the team in scoring, averaging 14.1 points per game for the competition.[36] His former USF and future Celtics teammate K. C. Jones, joined him on the Olympic squad and contributed 10.9 points per game.[37]

Boston Celtics

1956–59

Due to Russell's Olympic commitment, he could not join the Celtics for the 1956–57 season until December. After rejoining the Celtics, Russell played 48 games, averaging 14.7 points per game and a league-high 19.6 rebounds per game.[38] During this season, the Celtics featured five future Hall-of-Famers: center Russell, forwards Heinsohn and Frank Ramsey, and guards Bill Sharman and Bob Cousy. (K.C. Jones did not play for the Celtics until 1958 because of military service.)[39]

Russell's first Celtics game came on Dec. 22, 1956, against the St. Louis Hawks, led by star forward Bob Pettit, who would come to hold several all-time scoring records.[40] Auerbach assigned Russell to shut down the Hawks' main scorer, and the rookie impressed the Boston crowd with his man-to-man defense and shot-blocking.[40] In previous years, the Celtics had been a high-scoring team, but lacked the defensive presence needed to close out tight games. However, with the added defensive presence of Russell, the Celtics had laid the foundation for a dynasty. The team utilized a strong defensive approach to the game, forcing opposing teams to commit many turnovers, which led to many easy points on fast breaks.[40] Russell was an elite help defender who allowed the Celtics to play the so-called "Hey, Bill" defense: whenever a Celtic requested additional defensive help, he would shout "Hey, Bill!" Russell was so quick that he could run over for a quick double team and make it back in time if the opponents tried to find the open man.[40] He also became famous for his shot-blocking skills: pundits called his blocks "Wilsonburgers", referring to the Wilson NBA basketballs he "shoved back into the faces of opposing shooters".[40] This skill also allowed the other Celtics to play their men aggressively: if they were beaten, they knew that Russell was guarding the basket.[40] This approach allowed the Celtics to finish with a 44–28 regular season record, the team's second-best record since beginning play in the 1946–47 season, and guaranteed a post-season appearance.[41]

At the same time, Russell received much negative publicity as a player. He was notorious for his public surliness and judgmental attitude towards others. Because Russell ignored virtually any well-wisher who approached him home or away, not to mention the vast majority of media, his autograph was among the most difficult to secure of any pro athlete of his time. Constantly provoked by New York Knicks center Ray Felix during a game, he complained to coach Auerbach, who told him to take matters into his own hands. After the next provocation, Russell pounded Felix to the point of unconsciousness, paid a modest $25 fine and rarely was the target of cheap fouls thereafter.[40] Russell had a more cordial relationship with many of his teammates with the notable exception of Heinsohn, his old rival and fellow rookie. Heinsohn felt that Russell resented him because the former was named the 1957 NBA Rookie of the Year. Many people thought that Russell was more important even though he had only played half the season. Russell also ignored Heinsohn's request for an autograph on behalf of his cousin and openly said to Heinsohn that he deserved half of his $300 Rookie of the Year check. The relationship between the two was tenuous at best.[42] However, despite their different ethnic backgrounds and lack of common off-court interests, his relationship with Celtics point guard and fan favorite Bob Cousy was amicable.[43]

In Game 1 of the Eastern Division Finals, the Celtics met the Syracuse Nationals, who were led by Dolph Schayes. In Russell's first NBA playoff game, he finished with 16 points and 31 rebounds, along with a reported seven blocks. (At the time, blocks were not yet an officially registered statistic.) After the Celtics' 108–89 victory, Schayes quipped, "How much does that guy make a year? It would be to our advantage if we paid him off for five years to get away from us in the rest of this series."[33] The Celtics swept the Nationals in three games to earn the franchise's first appearance in the NBA Finals.[44]

In the NBA Finals, the Celtics met the St. Louis Hawks, who were again led by Bob Pettit, as well as former Celtic Ed Macauley. The teams split the first six games, and the tension was so high that, in Game 3, Celtics coach Auerbach punched his colleague Ben Kerner and received a $300 fine.[42] In the highly competitive Game 7, Russell tried his best to slow down Pettit, but it was Heinsohn who scored 37 points and kept the Celtics alive.[42] However, Russell contributed by completing the famous "Coleman Play". Here, Russell ran down Hawks guard Jack Coleman, who had received an outlet pass at midcourt, and blocked his shot despite the fact that Russell had been standing at his own baseline when the ball was thrown to Coleman. The block preserved Boston's slim 103–102 lead with 40-odd seconds left to play in regulation, saving the game for the Celtics.[33] In the second overtime, both teams were in serious foul trouble: Heinsohn had fouled out, and the Hawks were so depleted that they had only 7 players left.[42] With the Celtics leading 125–123 with one second left, the Hawks had the ball at their own baseline. Reserve guard Alex Hannum threw a long alley oop pass to Pettit, and Pettit's tip-in rolled indecisively on the rim for several seconds before rolling out again. The Celtics won, earning their first NBA Championship.[42]

At the start of the 1957–58 season, the Celtics won 14 straight games, and continued to succeed.[4] Russell averaged 16.6 points per game and a league-record average of 22.7 rebounds per game.[38] An interesting phenomenon began that year: Russell was voted the NBA Most Valuable Player, but only named to the All-NBA Second Team. This would occur repeatedly throughout his career. The NBA reasoned that other centers were better all-round players than Russell, but no player was more valuable to his team. The Celtics won 49 games and easily made the first berth in the 1958 NBA Playoffs, and made the 1958 NBA Finals against their familiar rivals, the St. Louis Hawks.[45] The teams split the first two games, but then Russell went down with a foot injury in Game 3 and only returned for Game 6. The Celtics surprisingly won Game 4, but the Hawks prevailed in Games 5 and 6, with Pettit scoring 50 points in the deciding Game 6.[45]

In the following 1958–59 season, Russell continued his strong play, averaging 16.7 points per game and 23.0 rebounds per game in the regular season.[38] The Celtics broke a league record by winning 52 games, and Russell's strong performance once again helped lead the Celtics through the post-season, as they returned to the NBA Finals. In the 1959 NBA Finals, the Celtics recaptured the NBA title, sweeping the Minneapolis Lakers 4–0.[46] Lakers head coach John Kundla praised Russell, stating, "We don't fear the Celtics without Bill Russell. Take him out and we can beat them ... He's the guy who whipped us psychologically."[33]

1959–66: Eight Straight Championships

In the 1959–60 season, the NBA witnessed the debut of legendary 7 ft 1 in (2.16 m) Philadelphia Warriors center Wilt Chamberlain, who averaged a record 37.6 points per game in his rookie year.[47] On November 7, 1959, Russell's Celtics hosted Chamberlain's Warriors, and pundits called the matchup between the best offensive and defensive centers "The Big Collision" and "Battle of the Titans".[48] Both men awed onlookers with "nakedly awesome athleticism",[48] and while Chamberlain outscored Russell 30 to 22, the Celtics won 115–106, and the match was called a "new beginning of basketball."[48] The matchup between Russell and Chamberlain became one of basketball's greatest rivalries.[1] On February 5, 1960, Russell grabbed 51 rebounds in a 124-100 win over the Syracuse Nationals.[49] It was the record for most rebounds in a single game until Chamberlain grabbed 55 rebounds.

In that season, Russell's Celtics won a record 59 regular season games (including a then-record tying 17 game win streak) and met Chamberlain's Warriors in the Eastern Division Finals. Chamberlain outscored Russell by 81 points in the series, but the Celtics walked off with a 4–2 series win.[50] In the 1960 Finals, the Celtics outlasted the Hawks 4–3 and won their third championship in four years.[41] Russell grabbed an NBA Finals-record 40 rebounds in Game 2, and added 22 points and 35 rebounds in the deciding Game 7, a 122–103 victory for Boston.[1][33]

In the 1960–61 season, Russell averaged 16.9 points and 23.9 rebounds per game,[38] leading his team to a regular season mark of 57–22. The Celtics earned another post-season appearance, where they defeated the Syracuse Nationals 4–1 in the Eastern Division Finals. The Celtics made good use of the fact that the Los Angeles Lakers had exhausted St. Louis in a long seven-game Western Conference Finals, and the Celtics convincingly won in five games.[51][52]

In the following season, Russell scored a career-high 18.9 points per game, accompanied by 23.6 rebounds per game.[38] While his rival Chamberlain had a record-breaking season of 50.4 points per game and a 100-point game,[47] the Celtics became the first team to win 60 games in a season, and Russell was voted as the NBA's Most Valuable Player. In the post-season, the Celtics met the Philadelphia Warriors with Chamberlain. Russell did his best to slow down the 50-points-per-game scoring Warriors center; in the pivotal Game 7, Russell managed to hold Chamberlain to only 22 points (28 below his season average) while scoring 19 himself. The game was tied with two seconds left when Sam Jones sank a clutch shot that won the Celtics the series.

In the 1962 NBA Finals, the Celtics met the Los Angeles Lakers with star forward Elgin Baylor and star guard Jerry West. The teams split the first six games. In Game 6, Russell recorded 19 points, 24 rebounds and 10 assists as the Celtics won 119-105.[53] Game 7 was tied one second before the end of regular time when Lakers guard Rod Hundley faked a shot and instead passed out to Frank Selvy, who missed an open eight-foot last-second shot that would have won L.A. the title.[54] Though the game was tied, Russell had the daunting task of defending against Baylor with little frontline help, as the three best Celtics forwards, Loscutoff, Heinsohn and Tom Sanders, had fouled out. In overtime, the fourth forward, Frank Ramsey, fouled out trying to guard Elgin Baylor, so Russell was completely robbed of his usual four-men wing rotation. But Russell and little-used fifth forward Gene Guarilia successfully pressured Baylor into missed shots.[54][55] Russell finished with a clutch performance, scoring 30 points and tying his own NBA Finals record with 40 rebounds in a 110–107 overtime win.[33]

The Celtics lost playmaker Bob Cousy to retirement after the 1962–63 season, but they drafted John Havlicek. Once again, the Celtics were powered by Russell, who averaged 16.8 points and 23.6 rebounds per game, won his fourth regular-season MVP title, and earned MVP honors at the 1963 NBA All-Star Game following his 19-point, 24-rebound performance for the East.[38] Russell recorded his first career triple-double after putting up 17 points, 19 rebounds and 10 assists in a 129-123 win over the Knicks.[56] At that time, he became the fourth player in Celtics history to have a triple-double, joining Ed Macauley, Bob Cousy and K.C. Jones.[57] The Celtics reached the 1963 NBA Finals, where they again defeated the Los Angeles Lakers, this time in six games.[58]

In the following 1963–64 season, the Celtics posted a league-best 58–22 record in the regular season. Russell scored 15.0 ppg and grabbed a career-high 24.7 rebounds per game, leading the NBA in rebounds for the first time since Chamberlain entered the league.[38] Boston defeated the Cincinnati Royals 4–1 to earn another NBA Finals appearance, and then won against Chamberlain's newly relocated San Francisco Warriors 4–1.[59] It was their sixth consecutive and seventh title in Russell's eighth year, a streak unreached in any U.S. professional sports league. Russell later called the Celtics' defense the best of all time.[1]

Russell again excelled during the 1964–65 season. The Celtics won a league-record 62 games, and Russell averaged 14.1 points and 24.1 rebounds per game, winning his second consecutive rebounding title and his fifth MVP award.[38] In the 1965 NBA Playoffs, the Celtics played the Eastern Division Finals against the Philadelphia 76ers, who had recently traded for Wilt Chamberlain. Russell held Chamberlain to a pair of field goals in the first three quarters of Game 3. In Game 5, Russell contributed 28 rebounds, 10 blocks, seven assists and six steals.[33] However, that playoff series ended in a dramatic Game 7. Five seconds before the end, the Sixers were trailing 110–109, but Russell turned over the ball. However, when the Sixers' Hall-of-Fame guard Hal Greer inbounded, John Havlicek stole the ball, causing Celtics commentator Johnny Most to scream: "Havlicek stole the ball! It's all over! Johnny Havlicek stole the ball!"[1] After the Division Finals, the Celtics had an easier time in the NBA Finals, winning 4–1 against the Los Angeles Lakers with Jerry West and Elgin Baylor.[60]

In the following 1965–66 season, the Celtics won their eighth consecutive title. Russell's team again beat Chamberlain's Philadelphia 76ers 4 games to 1 in the Division Finals, proceeding to win the NBA Finals in a tight seven-game showdown against the Los Angeles Lakers, with Russell scoring 25 points and grabbing 32 rebounds in a 95–93 win in the deciding seventh game.[61] During the season, Russell contributed 12.9 points and 22.8 rebounds per game. This was the first time in seven years that he failed to average at least 23 rebounds a game. [38]

1966–69

Celtics coach Red Auerbach retired before the 1966–67 season. He had initially wanted his old player Frank Ramsey to coach the Celtics, but Ramsey was too occupied running his three lucrative nursing homes.[63] His second choice was Bob Cousy, who declined the invitation, stating that he did not want to coach his former teammates.[63] Third choice Tom Heinsohn also said no, because he did not think he could handle the often surly Russell.[63] However, Heinsohn proposed Russell himself as a player-coach, and when Auerbach asked his center, he said yes.[63] On April 16, 1966, Bill Russell agreed to become head coach of the Boston Celtics; a public announcement was made two days later.[64] Russell thus became the first black head coach in NBA history[1] and commented to journalists: "I wasn't offered the job because I am a Negro, I was offered it because Red figured I could do it."[63] The Celtics' championship streak ended at eight in his first full season as head coach when Wilt Chamberlain's Philadelphia 76ers won a record-breaking 68 regular season games and beat the Celtics 4–1 in the 1967 Eastern Finals.[65] The Sixers simply outpaced the Celtics when they shredded the famed Boston defense by scoring 140 points in the clinching Game 5 win.[66] Russell acknowledged the first real loss of his career (he had been injured in 1958 when the Celtics lost the NBA Finals) by visiting Chamberlain in the locker room, shaking his hand and saying, "Great".[66] However, the game still ended on a high note for Russell. After the loss, he led his grandfather through the Celtics locker rooms, and the two saw white Celtics player John Havlicek taking a shower next to his black teammate Sam Jones and discussing the game. Suddenly, Jake Russell broke down crying. Asked by his grandson what was wrong, his grandfather replied how proud he was of him, being coach of an organization in which blacks and whites coexisted in harmony.[66]

In Russell's penultimate season of 1967–68, his numbers slowly declined, but at age 34, he still tallied 12.5 points per game and 18.6 rebounds per game[38] (the latter good for the third highest average in the league).[67] In the Eastern Division Finals, the 76ers had the better record than the Celtics and were slightly favored. But then, national tragedy struck on April 4, with the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. With eight of the ten starting players on Sixers and Celtics being black, both teams were in deep shock, and there were calls to cancel the series.[68] In a game called as "unreal" and "devoid of emotion", the Sixers lost 127–118 on April 5. In Game 2, Philadelphia evened the series with a 115–106 win, and in Games 3 and 4, the Sixers won, with Chamberlain suspiciously often defended by Celtics backup center Wayne Embry, causing the press to speculate Russell was worn down.[68] Prior to Game 5, the Celtics seemed dead: no NBA team had ever come back from a 3–1 deficit.[68] However, the Celtics rallied back, winning Game 5 122–104 and Game 6 114–106, powered by a spirited Havlicek and helped by a terrible Sixers shooting slump.[68] In Game 7, 15,202 stunned Philadelphia fans witnessed a historic 100–96 defeat, making it the first time in NBA history a team lost a series after leading 3–1. Russell limited Chamberlain to only two shot attempts in the second half.[33] Despite this, the Celtics were leading only 97–95 with 34 seconds left when Russell closed out the game with several consecutive clutch plays. He made a free throw, blocked a shot by Sixers player Chet Walker, grabbed a rebound off a miss by Sixers player Hal Greer, and finally passed the ball to teammate Sam Jones, who scored to clinch the win. Boston then beat the Los Angeles Lakers 4–2 in the NBA Finals, giving Russell his tenth title in 12 years.[1] For his efforts Russell was named Sports Illustrated's Sportsman of the Year. After losing for the fifth straight time against Russell and his Celtics, Hall-of-Fame Lakers guard Jerry West stated, "If I had a choice of any basketball player in the league, my No.1 choice has to be Bill Russell. Bill Russell never ceases to amaze me."[33]

However, Russell seemed to reach a breaking point during the 1968–69 season. He was shocked by the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, disillusioned by the Vietnam War, and weary from his increasingly stale marriage to his wife Rose; the couple later divorced. He was convinced that the U.S. was a corrupt nation and that he was wasting his time playing something as superficial as basketball.[69] He was 15 pounds overweight, skipped mandatory NBA coach meetings and was generally lacking energy: after a New York Knicks game, he complained of intense pain and was diagnosed with acute exhaustion.[69] Russell pulled himself together and put up 9.9 points and 19.3 rebounds per game,[38] but the aging Celtics stumbled through the regular season. Their 48–34 record was the team's worst since 1955–56, and they entered the playoffs as only the fourth-seeded team in the East.[70] In the playoffs, however, Russell and his Celtics achieved upsets over the Philadelphia 76ers and New York Knicks to earn a meeting with the Los Angeles Lakers in the NBA Finals. L.A. now featured new recruit Wilt Chamberlain next to perennial stars Baylor and West, and were heavily favored. In the first two games, Russell ordered not to double-team West, who used the freedom to score 53 and 41 points in the Game 1 and 2 Laker wins.[71] Russell then ordered to double-team West, and Boston won Game 3. In Game 4, the Celtics were trailing by one point with seven seconds left and the Lakers having the ball, but then Baylor stepped out of bounds, and in the last play, Sam Jones used a triple screen by Bailey Howell, Larry Siegfried and Havlicek and hit a buzzer beater which equalized the series.[71] The teams split the next two games, so it all came down to Game 7 in L.A., where Lakers owner Jack Kent Cooke angered and motivated the Celtics by putting "proceedings of Lakers victory ceremony" on the game leaflets. Russell used a copy as extra motivation and told his team to play a running game, because in that case, not the better, but the more determined team was going to win.[71]

The Celtics were ahead by nine points with five minutes remaining; in addition, West was heavily limping after a Game 5 thigh injury and Chamberlain had left the game with an injured leg.[71] West then hit one basket after the other and cut the lead to one, and Chamberlain asked to return to the game. However, Lakers coach Bill van Breda Kolff kept Chamberlain on the bench until the end of the game, saying later that he wanted to stay with the lineup responsible for the comeback.[47][72] The Celtics held on for a 108–106 victory, and Russell claimed his eleventh championship in 13 years. At age 35, Russell contributed 21 rebounds in his last NBA game.[33] After the game, Russell went over to the distraught West (who had scored 42 points and was named the only NBA Finals MVP in history from the losing team), clasped his hand and tried to soothe him.[71] Days later, 30,000 enthusiastic Celtics fans cheered their returning heroes, but Russell was not there: the man who said he owed the public nothing ended his career and cut all ties to the Celtics.[71] It was so surprising that even Red Auerbach was blindsided, and as a consequence, he made the "mistake" of drafting guard Jo Jo White instead of a center.[73] Although White became a standout Celtics player, the Celtics lacked an All-Star center, went just 34–48 in the next season and failed to make the playoffs for the first time since 1950.[41] In Boston, both fans and journalists felt betrayed, because Russell left the Celtics without a coach and a center and sold his retirement story for $10,000 to Sports Illustrated. Russell was accused of selling out the future of the franchise for a month of his salary.[73]

Post-playing career

Russell's No. 6 jersey was retired by the Celtics on March 12, 1972,[74] Russell had worn the same number 6 at the University of San Francisco and for the 1956 USA Olympic Team.[75] He was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1975. Russell, who had a difficult relationship with the media, did not attend either ceremony.[76]

After retiring as a player, Russell had stints as head coach of the Seattle SuperSonics (1973–1977) and Sacramento Kings (1987–1988). His time as a non-player coach was lackluster; although he led the struggling SuperSonics into the playoffs for the first time in franchise history, Russell's defensive, team-oriented Celtics mindset did not mesh well with the team, and he left in 1977 with a 162–166 record. Russell's stint with the Kings was considerably shorter, his last assignment ending when the Kings went 17–41 to begin the 1987–88 season.[77]

In addition, Russell ran into financial trouble. He had invested $250,000 in a rubber plantation in Liberia, where he had wanted to spend his retirement, but it went bankrupt.[78] The same fate awaited his Boston restaurant called "Slade's", after which he had to default on a $90,000 government loan to purchase the outlet. The IRS discovered that Russell owed $34,430 in tax money and put a lien on his house.[79]

Russell became a vegetarian, took up golf and worked as a color commentator for CBS and TBS throughout the 1970s into the mid-1980s, but he was uncomfortable as a broadcaster. He later said, "The most successful television is done in eight-second thoughts, and the things I know about basketball, motivation, and people go deeper than that."[1][79] On November 3, 1979, Russell hosted Saturday Night Live, in which he appeared in several sports-related sketches. Russell also wrote books, usually written as a joint project with a professional writer, including 1979's Second Wind. In 1986 Russell played Judge Roger Ferguson in the Miami Vice episode "The Fix" (aired March 7, 1986).

Russell made few public appearances in the early 1990s, living as a near-recluse on Mercer Island near Seattle. Following Chamberlain's death in October 1999, Russell returned to prominence at the turn of the millennium.[80] Russell's Rules was published in 2001, and in January 2006, he convinced Miami Heat superstar center Shaquille O'Neal to bury the hatchet with fellow NBA superstar and former Los Angeles Lakers teammate Kobe Bryant, with whom O'Neal had a bitter public feud.[81] Later that year, on November 17, 2006, the two-time NCAA winner Russell was recognized for his impact on college basketball as a member of the founding class of the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame. He was one of five, along with John Wooden, Oscar Robertson, Dean Smith and Dr. James Naismith, selected to represent the inaugural class.[82] On May 20, 2007, Russell was awarded an honorary doctorate by Suffolk University, where he served as its commencement speaker. Russell also received honorary degrees from Harvard University on June 7, 2007 and from Dartmouth College on June 14, 2009. On June 18, 2007, Russell was inducted as a member of the founding class of the FIBA Hall of Fame. In 2008, Russell received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[83][84] Russell was also honored during the 2009 NBA All-Star Weekend in Phoenix.

On February 14, 2009, NBA Commissioner David Stern announced that the NBA Finals Most Valuable Player Award would be renamed the "Bill Russell NBA Finals Most Valuable Player Award" in honor of the 11-time NBA champion.[85] The following day, during halftime of the All-Star game, Celtics captains Paul Pierce, Kevin Garnett, and Ray Allen presented Russell a surprise birthday cake for his 75th birthday.[86] Russell attended the final game of the Finals that year to present his newly christened namesake award to its winner, Kobe Bryant.[87][88] Russell was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama in 2011.[89] Russell and Kobe Bryant were spectators to a basketball game for Obama's 50th birthday at the basketball court at the White House. The game featured Shane Battier, LeBron James, Magic Johnson, Maya Moore, Alonzo Mourning, Joakim Noah, Chris Paul and Derrick Rose and Obama's friends from high school.[90]

Accomplishments and legacy

Russell is one of the most successful and decorated athletes in North American sports history. His awards and achievements include 11 NBA championships as a player with the Boston Celtics in 13 seasons (including two NBA championships as player/head coach), and he is credited with having raised defensive play in the NBA to a new level.[91] By winning the 1956 NCAA Championship with USF and the 1957 NBA title with the Celtics, Russell became the first of only four players in basketball history to win an NCAA championship and an NBA Championship back-to-back (the others being Henry Bibby, Magic Johnson, and Billy Thompson). He also won two state championships in high school. In the interim, Russell won an Olympic gold medal in 1956. His stint as coach of the Celtics was also of historical significance, as he became the first black head coach in major U.S. professional sports when he succeeded Red Auerbach.[92]

In his first NBA full season (1957–58), Russell became the first player in NBA history to average more than 20 rebounds per game for an entire season, a feat he accomplished 10 times in his 13 seasons. Russell's 51 rebounds in a single game is the second-highest performance ever, trailing only Chamberlain's all-time record of 55. He still holds the NBA record for rebounds in one half with 32 (vs. Philadelphia, on November 16, 1957). Career-wise in rebounds, Russell ranks second to Wilt Chamberlain in regular season total (21,620) and average per game (22.5), and he led the NBA in average rebounds per game four times. Russell is the all-time playoff leader in total (4,104) and average (24.9) rebounds per game, he grabbed 40 rebounds in three separate playoff games (twice in the NBA Finals), and he never failed to average at least 20 rebounds per game in any of his 13 post-season campaigns. Russell also had seven regular season games with 40 or more rebounds, the NBA Finals record for highest rebound per game average (29.5 rpg, 1959) and by a rookie (22.9 rpg, 1957). In addition, Russell holds the NBA Finals single-game record for most rebounds (40, March 29, 1960, vs. St. Louis, and April 18, 1962, vs. Los Angeles), most rebounds in a quarter (19, April 18, 1962 vs. Los Angeles), and most consecutive games with 20 or more rebounds (15 from April 9, 1960 – April 16, 1963).[93] He also had 51 in one game, 49 in two others, and 12 straight seasons of 1,000 or more rebounds.[1] Russell was known as one of the most clutch players in the NBA. He played in 11 deciding games (10 times in Game 7s, once in a Game 5), and ended with a flawless 11–0 record. In these 11 games, Russell averaged 18 points and 29.45 rebounds.[33]

Russell was considered the consummate defensive center, noted for his defensive intensity, basketball IQ, and will to win.[33] He excelled at playing man-to-man defense, blocking shots and grabbing defensive rebounds.[1] Opponent Wilt Chamberlain said Russell's timing as a shot-blocker was unparalleled.[94] Bill Bradley—Russell's erstwhile Knicks opponent—wrote in 2009 that Russell "was the smartest player ever to play the game [of basketball]".[95] He also could score with putbacks and made mid-air outlet passes to point guard Bob Cousy for easy fast break points.[1] He also was known as a fine passer and pick-setter, featured a decent left-handed hook shot and finished strong on alley oops.[33] However, on offense, Russell's output was limited. His NBA career personal averages show him to be an average scorer (15.1 points career average), a poor free throw shooter (56.1%), and average overall shooter from the field (44%, not exceptional for a center). In his 13 years, he averaged a relatively low 13.4 field goals attempted (normally, top scorers average 20 and more), illustrating that he was never the focal point of the Celtics offense, instead focusing on his tremendous defense.[38]

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

In his career, Russell won five regular season MVP awards (1959, 1961–63, 1965)—tied with Michael Jordan for second all-time behind Kareem Abdul-Jabbar's six awards. He was selected three times to the All-NBA First Teams (1959, 1963, 1965) and eight Second Teams (1958, 1960–62, 1964, 1966–68), and was a 12-time NBA All-Star (1958–1969). Russell was elected to one NBA All-Defensive First Team. This took place during his last season (1969), and was the first season the NBA All-Defensive Teams were selected. In 1970, The Sporting News named Russell the "Athlete of the Decade". Russell is universally seen as one of the best NBA players ever,[1] and was declared "Greatest Player in the History of the NBA" by the Professional Basketball Writers Association of America in 1980.[1] For his achievements, Russell was named "Sportsman of the Year" by Sports Illustrated in 1968. He also made all three NBA Anniversary Teams: the NBA 25th Anniversary All-Time Team (1970), the NBA 35th Anniversary All-Time Team (1980) and the NBA 50th Anniversary All-Time Team (1996). Russell ranked #18 on ESPN's 50 Greatest Athletes of the 20th Century in 1999. In 2009, SLAM Magazine named Russell the #3 player of all time behind Michael Jordan and Wilt Chamberlain.[96] Former NBA player and head coach, Don Nelson, described Russell as follows: "There are two types of superstars. One makes himself look good at the expense of the other guys on the floor. But there's another type who makes the players around him look better than they are, and that's the type Russell was."[97]

On February 14, 2009, during the 2009 NBA All-Star Weekend in Phoenix, NBA Commissioner David Stern announced that the NBA Finals MVP Award would be named after Bill Russell.[85] Russell was named as a 2010 recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom.[98] On June 15, 2017, Russell was announced as the inaugural recipient of the NBA Lifetime Achievement Award.

In 2000, his longtime teammate Tommy Heinsohn described both Russell's stature and his uneasy relationship with Boston more earthily: "Look, all I know is the guy...came to Boston and won 11 championships in 13 years, and they named a bleeping tunnel after Ted Williams."[99]

Statue

Boston honored Russell by erecting a statue of him on City Hall Plaza in 2013: he is depicted in-game, surrounded by 11 plinths representing the 11 championships he helped the Celtics win.[100] Each plinth features a key word and related quote to illustrate Russell's multiple accomplishments. The Bill Russell Legacy Foundation, established by the Boston Celtics Shamrock Foundation, funded the project.[101] The art is by Ann Hirsch of Somerville, Massachusetts, in collaboration with Pressley Associates Landscape Architects of Boston. The statue was unveiled on November 1, 2013, with Russell in attendance. Two years later, during the spring of 2015, two statues of children were added, honoring Bill Russell's commitment to working with children. These statues were modeled by a local boy from Somerville and multiple girls from the surrounding area.[102][103][104][105]

West Coast Conference: The Russell Rule

On August 2, 2020, the West Coast Conference (WCC), which has been home to Russell's alma mater of USF since the league's formation in 1952,[106][lower-alpha 1] became the first NCAA Division I conference to adopt a conference-wide diversity hiring commitment, announcing the "Russell Rule", named after Russell and based on the NFL's Rooney Rule. In its announcement, the WCC stated:[107]

The “Russell Rule” requires each member institution to include a member of a traditionally underrepresented community in the pool of final candidates for every athletic director, senior administrator, head coach and full-time assistant coach position in the athletic department.

NBA career statistics

| GP | Games played | GS | Games started | MPG | Minutes per game |

| FG% | Field goal percentage | 3P% | 3-point field goal percentage | FT% | Free throw percentage |

| RPG | Rebounds per game | APG | Assists per game | SPG | Steals per game |

| BPG | Blocks per game | PPG | Points per game | Bold | Career high |

| † | Won an NBA championship | * | Led the league | |

NBA record |

Regular season

| Year | Team | GP | MPG | FG% | FT% | RPG | APG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1956–57† | Boston | 48 | 35.3 | .427 | .492 | 19.6* | 1.8 | 14.7 |

| 1957–58 | Boston | 69 | 38.3 | .442 | .519 | 22.7* | 2.9 | 16.6 |

| 1958–59† | Boston | 70 | 42.6* | .457 | .598 | 23.0* | 3.2 | 16.7 |

| 1959–60† | Boston | 74 | 42.5 | .467 | .612 | 24.0 | 3.7 | 18.2 |

| 1960–61† | Boston | 78 | 44.3 | .426 | .550 | 23.9 | 3.4 | 16.9 |

| 1961–62† | Boston | 76 | 45.2 | .457 | .575 | 23.6 | 4.5 | 18.9 |

| 1962–63† | Boston | 78 | 44.9 | .432 | .555 | 23.6 | 4.5 | 16.8 |

| 1963–64† | Boston | 78 | 44.6 | .433 | .550 | 24.7* | 4.7 | 15.0 |

| 1964–65† | Boston | 78 | 44.4 | .438 | .573 | 24.1* | 5.3 | 14.1 |

| 1965–66† | Boston | 78 | 43.4 | .415 | .551 | 22.8 | 4.8 | 12.9 |

| 1966–67 | Boston | 81 | 40.7 | .454 | .610 | 21.0 | 5.8 | 13.3 |

| 1967–68† | Boston | 78 | 37.9 | .425 | .537 | 18.6 | 4.6 | 12.5 |

| 1968–69† | Boston | 77 | 42.7 | .433 | .526 | 19.3 | 4.9 | 9.9 |

| Career | 963 | 42.3 | .440 | .561 | 22.5 | 4.3 | 15.1 | |

Playoffs

| Year | Team | GP | MPG | FG% | FT% | RPG | APG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1957† | Boston | 10 | 40.9 | .365 | .508 | 24.4 | 3.2 | 13.9 |

| 1958 | Boston | 9 | 39.4 | .361 | .606 | 24.6 | 2.7 | 15.1 |

| 1959† | Boston | 11 | 45.1 | .409 | .612 | 27.7 | 3.6 | 15.5 |

| 1960† | Boston | 13 | 44.0 | .456 | .707 | 25.8 | 2.9 | 18.5 |

| 1961† | Boston | 10 | 46.2 | .427 | .523 | 29.9 | 4.8 | 19.1 |

| 1962† | Boston | 14 | 48.0 | .458 | .726 | 26.4 | 5.0 | 22.4 |

| 1963† | Boston | 13 | 47.5 | .453 | .661 | 25.1 | 5.1 | 20.3 |

| 1964† | Boston | 10 | 45.1 | .356 | .552 | 27.2 | 4.4 | 13.1 |

| 1965† | Boston | 12 | 46.8 | .527 | .526 | 25.2 | 6.3 | 16.5 |

| 1966† | Boston | 17 | 47.9 | .475 | .618 | 25.2 | 5.0 | 19.1 |

| 1967 | Boston | 9 | 43.3 | .360 | .635 | 22.0 | 5.6 | 10.6 |

| 1968† | Boston | 19 | 45.7 | .409 | .585 | 22.8 | 5.2 | 14.4 |

| 1969† | Boston | 18 | 46.1 | .423 | .506 | 20.5 | 5.4 | 10.8 |

| Career | 165 | 45.4 | .430 | .603 | 24.9 | 4.7 | 16.2 | |

Head coaching record

| Regular season | G | Games coached | W | Games won | L | Games lost | W–L % | Win–loss % |

| Playoffs | PG | Playoff games | PW | Playoff wins | PL | Playoff losses | PW–L % | Playoff win–loss % |

| Team | Year | G | W | L | W–L% | Finish | PG | PW | PL | PW–L% | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston | 1966–67 | 81 | 60 | 21 | .671 | 2nd in Eastern | 9 | 4 | 5 | .444 | Lost in Div. Finals |

| Boston | 1967–68 | 82 | 54 | 28 | .659 | 2nd in Eastern | 19 | 12 | 7 | .632 | Won NBA Championship |

| Boston | 1968–69 | 82 | 48 | 34 | .585 | 4th in Eastern | 18 | 12 | 6 | .667 | Won NBA Championship |

| Seattle | 1973–74 | 82 | 36 | 46 | .439 | 3rd in Pacific | — | — | — | — | Missed Playoffs |

| Seattle | 1974–75 | 82 | 43 | 39 | .524 | 2nd in Pacific | 9 | 4 | 5 | .444 | Lost in Conf. Semifinals |

| Seattle | 1975–76 | 82 | 43 | 39 | .524 | 2nd in Pacific | 6 | 2 | 4 | .333 | Lost in Conf. Semifinals |

| Seattle | 1976–77 | 82 | 40 | 42 | .488 | 4th in Pacific | — | — | — | — | Missed Playoffs |

| Sacramento | 1987–88 | 58 | 17 | 41 | .293 | (released) | — | — | — | — | — |

| Career | 631 | 341 | 290 | .540 | 61 | 34 | 27 | .557 |

Personal life

Russell was married to his college sweetheart Rose Swisher from 1956 to 1973. They had three children, daughter Karen Russell, the television pundit and lawyer, and sons William Jr. and Jacob. However, the couple grew emotionally distant and divorced.[108] In 1977, he married Dorothy Anstett, Miss USA of 1968,[108] but they divorced in 1980. The relationship was shrouded in controversy because Anstett was white.[109] In 1996, Russell married his third wife, Marilyn Nault;[110] their marriage lasted until her death in January 2009.[111] As of 2020, Russell is married to Jeannine Russell.[112] He has been a resident of Mercer Island, Washington for over four decades.[113] His older brother was the noted playwright Charlie L. Russell.[114]

In 1959, Russell became the first NBA player to visit Africa.[115] Russell is a member of Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity, having been initiated into its Gamma Alpha chapter while a student at University of San Francisco.[116] On October 16, 2013, Russell was arrested for bringing a loaded .38-caliber Smith & Wesson handgun to the Seattle–Tacoma International Airport.[117]

Earnings

During his career, Russell was one of the first big earners in NBA basketball. His 1956 rookie contract was worth $24,000, only fractionally smaller than the $25,000 of top earner Bob Cousy.[40] Russell never had to work part-time. This was in contrast to other Celtics who had to work during the offseason to maintain their standard of living. Heinsohn sold insurance, Gene Guarilia was a professional guitar player, Cousy ran a basketball camp, and Auerbach invested in plastics and a Chinese restaurant.[118] When Wilt Chamberlain became the first NBA player to earn $100,000 in salary in 1965, Russell went to Auerbach and demanded a $100,001 salary, which he promptly received.[119][120] For his promotion to coach, the Celtics paid Russell an annual salary of $25,000 which was in addition to his salary as a player. Although the salary was touted in the press as a record for an NBA coach, it is unclear whether Russell's continued $100,001 salary as a player was included in the calculation.[121]

Personality

In 1966, The New York Times wrote "Russell's main characteristics are pride, intelligence, an active and appreciative sense of humor, a preoccupation with dignity, a capacity for consideration once his friendship or sympathy has been aroused, and an unwillingness to compromise whatever truths he has accepted."[122] Russell himself in 2009 wrote his paternal grandfather's motto, passed down to his father and then to him is: "A man has to draw a line inside himself that he won't allow any man to cross."; Russell was "proud of my grandfather's heroic dignity against forces more powerful than him... he would not allow himself to be oppressed or intimidated by anyone."; he wrote these words after recounting how grandfather Jake had stood up to the Ku Klux Klan and whites who attempted to thwart his efforts to build a schoolhouse for black children (Jake Russell was the first person in Bill Russell's patrilineal line born free in North America, and was himself illiterate.[123]).[124] Thus Bill Russell's motto became, "If you disrespect that line, you disrespect me."[125]

As a competitor

Russell was driven by "a neurotic need to win", as his Celtic teammate Heinsohn observed.[78] He was so tense before every game that he regularly vomited in the locker room; early in his career it happened so frequently that his fellow Celtics were more worried when it did not happen.[126] Later in Russell's career, Havlicek said of his teammate and coach that he threw up less often than early in his career, only doing so "when it's an important game or an important challenge for him—someone like Chamberlain, or someone coming up that everyone's touting. [The sound of Russell throwing up] is a welcome sound, too, because it means he's keyed up for the game, and around the locker room we grin and say, "Man, we're going to be all right tonight."[127]

In a retrospective interview, Russell described the state of mind he felt he needed to enter in order to be able to play basketball as, "I had to almost be in a rage. Nothing went on outside the borders[] of the court. I could hear anything, I could see anything, and nothing mattered. And I could anticipate every move that every player made."[128]

Russell was also known for his natural authority. When he became player-coach in 1966, Russell bluntly said to his teammates that "he intended to cut all personal ties to other players", and seamlessly made the transition from their peer to their superior.[129] Russell, at the time his additional role of coach was announced, publicly stated he believed Auerbach's (who he regarded as the greatest of all coaches) impact as a coach confined every or almost every relationship with each Celtic player to a strictly professional one.[130]

Off the court

Russell was known for his distinctive high-pitched laugh (hear at [131]) of which Auerbach quipped, "There are only two things that could make me quit coaching[:] My wife and Russell's laugh."[132] To teammates and friends, Russell was open and amicable, but was extremely distrusting and cold towards anyone else.[78] Journalists were often treated to the "Russell Glower", described as an "icily contemptuous stare accompanied by a long silence".[78] Russell was also notorious for his refusal to give autographs or even acknowledge the Celtics fans, and was called "the most selfish, surly and uncooperative athlete" by one pundit.[78]

Russell–Chamberlain relations

For most of his career, Russell and his perennial opponent Wilt Chamberlain were close friends. Chamberlain often invited Russell over for Thanksgiving dinner, and at Russell's place, conversation mostly concerned Russell's electric trains.[133] However, the close relationship ended after Game 7 of the 1969 NBA Finals, when Chamberlain injured his knee with six minutes left and was forced to leave the game. During a conversation with students, a reporter—unknown to Russell—heard Russell describe Chamberlain as a malingerer and accused him of "copping out" of the game when it seemed that the Lakers would lose.[134] Chamberlain was livid with Russell and saw him as a backstabber.[134] Chamberlain's knee was injured so badly that he could not play the entire offseason and he ruptured it the next season. The two men did not speak to each other for more than 20 years until Russell finally met with Chamberlain and personally apologized.[135] After that, the two were often seen together at various events and interviewed as friends. When Chamberlain died in 1999, Chamberlain's nephew said that Russell was the second person he was told to call.[7] At Chamberlain's eulogy, Russell stated that he did not consider them to be rivals, but rather to have a competition, and that the pair would "be friends through eternity."[136]

Racist abuse, controversy, and relationship with Boston fans

Russell's life was marked by an uphill battle against racism and controversial actions and statements in response to perceived racism. As a child he witnessed how his parents were victims of racial abuse, and the family eventually moved into government housing projects to escape the daily torrent of bigotry.[5] When he later became a standout college player at USF, Russell recalled how he and his few fellow black teammates were jeered by white students.[20] Even after he became a star with the Boston Celtics, Russell was the victim of racial abuse. When the NBA All-Stars toured the U.S. in the 1958 offseason, white hotel owners in segregated North Carolina denied rooms to Russell and his black teammates, causing him to later write in his memoir Go Up for Glory, "It stood out, a wall which understanding cannot penetrate. You are a Negro. You are less. It covered every area. A living, smarting, hurting, smelling, greasy substance which covered you. A morass to fight from."[43] Before the 1961–62 season, Russell's team was scheduled to play in an exhibition game in Lexington, Kentucky, when Russell and his black teammates were refused service at a local restaurant. He and the other black teammates refused to play in the exhibition game and flew home, drawing a great deal of controversy and publicity.[76]

As a consequence, Russell was extremely sensitive to all racial prejudice: according to Taylor, he often perceived insults even if others did not.[32] He was active in the Black Power movement and supported Muhammad Ali's decision to refuse to be drafted.[137] He was often called "Felton X", presumably in the tradition of the Nation of Islam's practice of replacing a European slave name with an "X", and even purchased land in Liberia.[78] Russell's public statements became increasingly militant, and he was quoted in a 1963 Sports Illustrated interview with the words: "I dislike most white people because they are people ... I like most blacks because I am black"; however, Russell articulated these views with a measure of self-criticism: "I consider this a deficiency in myself—maybe. If I looked at it objectively, detached myself, it would be a deficiency."[78][132] However, when his white Celtics teammate Frank Ramsey asked whether he hated him, Russell claimed to have been misquoted, but few believed it.[78]

According to Taylor, Russell discounted the fact that his career was facilitated by white people who were proven anti-racists: his high school coach George Powles (the person who encouraged him to play basketball), his college coach Phil Woolpert (who integrated USF basketball), Celtics coach Red Auerbach (who is regarded as an anti-racist pioneer and made him the first black NBA coach), and Celtics owner Walter A. Brown, who gave him a high $24,000 rookie contract, just $1,000 shy of the top earning veteran Bob Cousy.[79]

However, Russell in the above-quoted 1963 Sports Illustrated article said he had "never met a finer person [than George Powles]... I owe so much to him it's impossible to express."[132] Years after Taylor's book, Russell published an autobiographical account, Red and Me which chronicled his lifelong friendship with Auerbach. Bill Bradley for the New York Times Book Review wrote of Red and Me, "Bill Russell is a private, complex man, but on the subject of his love of Red Auerbach and his Celtic teammates, he's loud and clear."[95] In the book itself Russell wrote "Whenever I leave the Celtics locker room, even Heaven wouldn't be good enough because anywhere else is a step down... With Red [Auerbach] and Walter Brown, I was the freest athlete on the planet. I could always be myself with them and they were always there for me."[138] Describing the Celtics organization (as distinguished from Boston sports fans in the 1950s and 1960s) as very progressive racially, Russell in 2010 recalled a list of the organization's accomplishments on racial progress both in terms of objective milestones and his own subjective experience as a member of the organization:[139]

The Celtics were the first [NBA basketball] team to draft a black player, period:… [a] guy named Chuck Cooper from Duquesne… The first team to start five black players was the Boston Celtics… The first [NBA organization] to hire a black [head] coach was the Boston Celtics… and [they've] had at least five [black head-coaches] over the years.

And so [Walter Brown,] the… guy that owned the Celtics[,] was [in addition to Auerbach for whom Russell expressed "respect" and "actual love"] another one of the fine, good, and decent human beings that I've ever encountered… When the [Celtics] drafted Chuck Cooper and they came into Washington, D.C. to sign his contract, Walter Brown the owner of the team walked up to him and said 'Mr. Cooper, the Boston Celtics will never embarrass you.' That's the first thing Walter Brown said to Chuck Cooper. And that's the kind of guy [Brown] was.

And so the Celtics—all we looked for was: 'Can he play?' And what we would do is—[Auerbach] trusted all his players—so like when he'd make a coaching decision, he could talk: he talked to [Bob] Cousey [who is white], he talked to me [black], he talked to [Bill] Sharman [white], he talked to Sam [Jones] [black]—all of us: "What do you think?". [Auerbach would] get the information from us and then make a decision based on that information and his thoughts. So we never, or at least I never, ever considered him as having ulterior motives for whatever he did.

In 1966, Russell was promoted to head coach of the Boston Celtics. During a press conference, Russell was asked: "As the first Negro head coach in a major league sport, can you do the job impartially without any racial prejudice in reverse?" He replied "Yes." The reporter asked, "How?" Russell replied, "Because the most important factor is respect. And in basketball I respect a man for his ability, period."[64][140]

As a result of repeated racial bigotry, Russell refused to respond to fan acclaim or friendship from his neighbors, thinking it was insincere and hypocritical. This attitude contributed to his legendarily bad rapport with fans and journalists.[43] He alienated Celtics fans by saying, "You owe the public the same it owes you, nothing! I refuse to smile and be nice to the kiddies."[78] This supported the opinion of many white fans that Russell (who was by then the highest-paid Celtic) was egotistical, paranoid and hypocritical. The already hostile atmosphere between Russell and Boston hit its apex when vandals broke into his house, covered the walls with racist graffiti, damaged his trophies and defecated in the beds.[78] In response, Russell described Boston as a "flea market of racism".[141] In King Of The Court by Aram Goudsouzian, he was quoted saying, "From my very first year I thought of myself as playing for the Celtics, not for Boston. The fans could do or think whatever they wanted."[142] Referring to a time when the Celtics did not frequently sell out the Boston Garden (while the generally-mediocre and all-white NHL Boston Bruins did), Russell recalled "We [the Celtics] did a survey about what we could do to improve attendance. Over 50 percent of responses said 'There's too many black players.'"[143] In retirement, Russell described the Boston press as corrupt and racist; in response, Boston sports journalist Larry Claflin claimed that Russell himself was the real racist.[144]

The FBI maintained a file on Russell, and described him in their file as "an arrogant Negro who won't sign autographs for white children".[78][145]

Russell refused to attend the ceremony when his jersey #6 was retired in 1972; he also refused to attend his induction into the Hall of Fame in 1975.[76] While Russell still has sore feelings towards Boston, there has been something of a reconciliation;[146] on November 15, 2019 Russell did accept the Hall of fame ring in a private ceremony with family,[147] and he has even visited the city regularly in recent years, something he never did in the years immediately after his retirement.[146] When Russell originally retired, he demanded that his jersey be retired in an empty Boston Garden.[148] In 1995, the Celtics left Boston Garden and entered the FleetCenter, now the TD Garden, and as the main festive act, the Boston organization wanted to re-retire Russell's jersey in front of a sellout audience.[79] Perennially wary of what he long perceived as a racist city, Russell decided to make amends and gave his approval. On May 6, 1999, the Celtics re-retired Russell's jersey in a ceremony attended by his on-court rival (and friend) Chamberlain, along with Celtics legend Larry Bird and Hall of Famer Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. The crowd gave Russell a prolonged standing ovation, which brought tears to his eyes.[148] He thanked Chamberlain for taking him to the limit and "making [him] a better player" and the crowd for "allowing [him] to be a part of their lives."[79] In December 2008, the We Are Boston Leadership Award was presented to Russell.[149]

On September 26, 2017, Russell posted a photograph of himself to a previously unused Twitter account in which he was taking a knee in solidarity with NFL players kneeling during the US national anthem. Russell wore his Presidential Medal of Freedom, and the image was captioned with "Proud to take a knee, and to stand tall against social injustice." In an interview with ESPN, Russell said he wanted the NFL players to know they weren't alone.[150]

See also

- List of National Basketball Association career minutes played leaders

- List of National Basketball Association career rebounding leaders

- List of National Basketball Association career playoff rebounding leaders

- List of National Basketball Association annual minutes leaders

- List of NCAA Division I men's basketball career rebounding leaders

Selected publications

- Russell, Bill; McSweeny, William (1966). Go Up for Glory. Coward-McCann.

- Russell, Bill; Branch, Taylor (1979). Second Wind. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-394-50385-1.

- Russell, Bill; Hilburg, Alan; Faulkner, David (2001). Russell Rules. New American Library. ISBN 0-525-94598-9.

- Russell, Bill; Steinberg, Alan (2009). Red and Me: My Coach, My Lifelong Friend. Harper. ISBN 978-0-06-176614-5.

Footnotes

- During Russell's college career, the conference was known as the California Basketball Association.[106]

References

- "Bill Russell". National Basketball Association. Turner Sports Interactive. Archived from the original on November 12, 2006. Retrieved December 1, 2006.

- Daley, Arthur (February 24, 1957). "Education of a Rookie". The New York Times Magazine. 53.

- Holmes, Baxter (October 11, 2014). "Bill Russell, K.C. Jones treated like 'Rock' stars at Alcatraz". The Boston Globe. ALCATRAZ ISLAND, Calif.

- "NBA Encyclopedia, Playoff Edition". NBA Media Ventures, LLC. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- Thompson, Tim (February 19, 2001). "Bill Russell overcame long odds, dominated basketball". The Current (University of Missouri–St. Louis).

- Taylor, John (2005). The Rivalry: Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain, and the Golden Age of Basketball. New York City: Random House. pp. 52–56. ISBN 1-4000-6114-8.

- Russell, Bill. "Chat Transcript: Celtics Legend Bill Russell". National Basketball Association. Turner Sports Interactive. Retrieved December 1, 2006.

- "Russell "So good, he scares you" – Mikan". New York: The Afro-American. March 3, 1956. p. 15.

- "Bill Russell Bio". NBA.com.

- Bjarkman, Peter C (2002). Boston Celtics Encyclopedia. Basketball-Reference. p. 99. ISBN 1-58261-564-0.

- Wir sind stolz auf Dirk, Sven Simon, FIVE magazine, issue 43, 12/2007, p. 69.

- Bill Russell; Alan Steinberg (May 5, 2009). Red and Me: My Coach, My Lifelong Friend. HarperCollins. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-0-06-176614-5.

- O'Malley, Pat (December 12, 1990). "Who's Better At Hoops: Bill Russell Or Frank Robinson?". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- Taylor, John (2005). The Rivalry: Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain, and the Golden Age of Basketball. New York City: Random House. pp. 50–51. ISBN 1-4000-6114-8.

- Taylor, John (2005). The Rivalry: Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain, and the Golden Age of Basketball. New York City: Random House. pp. 57–67. ISBN 1-4000-6114-8.

- Schneider, Bernie (2006). "1953–56 NCAA Championship Seasons: The Bill Russell Years". University of San Francisco. Archived from the original on November 28, 2006. Retrieved December 1, 2006.

- Actual quotation from Sports Illustrated follows. Terrell, Roy (January 9, 1956). "The Tournaments and The Man Who". Sports Illustrated.

if [Russell] ever learns to hit the basket someone is going to have to revise the rules.

- Luke DeCock (December 6, 2005). Great Teams in College Basketball History. Raintree. pp. 1960–. ISBN 978-1-4109-1488-0.

- "Basketball Players who Caused Rule Changes by Ron Kurtus - Sports History: School for Champions". www.school-for-champions.com.

- Matthews, Chris (April 28, 2000). "Bill Russell and American racism". Jewish World Review. Retrieved February 9, 2007.

- "A conversation with Bill Russell". sportsillustrated.cnn.com. May 10, 1999. Archived from the original on February 27, 2007. Retrieved February 9, 2007.

- "A conversation with Bill Russell". usatoday.com. June 6, 2001. Retrieved February 9, 2007.

- "Bill Russell Biography and Interview". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- Johnson, James W. (2009). The Dandy Dons: Bill Russell, K. C. Jones, Phil Woolpert, and One of College Basketball's Greatest and Most Innovative Teams. Bison Books. p. 85. ISBN 9780803224445.

- Paul, Alan (2018). "An Interview With Bill Russell".

- "World Rankings — Men's High Jump" (PDF). 2019. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- "NCAA Basketball Tourney History: Two by Four". CBS Sportsline.com. Archived from the original on February 14, 2007. Retrieved February 23, 2007.

- Huntress, Frank (May 13, 1956). "Stanford Trackmen Finish Fourth in Fresno Relays; Leamon King Equals Century World Record; Landy Runs Mile in 3.59.1; Russell Nears Mark". The Stanford Daily.

USF's versatile Bill Russell and Compton's Charlie Dumas cleared 6-9"-1/4 and tried for the magic ceiling of seven feet. On his third attempt, Russell just missed breaking 6-9"-1/2, the record set by Walt Davis of Texas A&M

- "Bill Russell attempting to clear 6-9 1/4. (embedded photo)". Sports Illustrated – via The Associated Press.

- "Rare Photos of Bill Russell (third photo in gallery". Sports Illustrated. May 5, 2011. Archived from the original on April 12, 2017 – via The Associated Press).

- "Along Came Bill". Time. January 2, 1956. Retrieved February 23, 2007.

- Taylor, John (2005). The Rivalry: Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain, and the Golden Age of Basketball. New York City: Random House. pp. 66–71. ISBN 1-4000-6114-8.

- Ryan, Bob. "Timeless Excellence". National Basketball Association. Turner Sports Interactive. Retrieved December 1, 2006.

- Taylor, John (2005). The Rivalry: Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain, and the Golden Age of Basketball. New York City: Random House. pp. 67–74. ISBN 1-4000-6114-8.

- Auerbach, Red and John Feinstein. (2004). Let Me Tell You a Story: A Lifetime in the Game. Little, Brown and Company. pp. 75–6. ISBN 0-316-73823-9.

- 1956 Olympic Games : Tournament for Men.

- "Games of the XVIth Olympiad–1956". usabasketball.com. Archived from the original on September 10, 2008. Retrieved April 1, 2008.

- "Bill Russell Statistics". Basketball-Reference. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- Smith, Sam (October 30, 2006). "2003 draft eventually may be best in history". nbcsports.msnbc.com. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- Taylor, John (2005). The Rivalry: Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain, and the Golden Age of Basketball. New York City: Random House. pp. 74–80. ISBN 1-4000-6114-8.

- "Boston Celtics". Basketball-Reference. Archived from the original on December 8, 2006. Retrieved December 4, 2006.

- Taylor, John (2005). The Rivalry: Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain, and the Golden Age of Basketball. New York City: Random House. pp. 91–99. ISBN 1-4000-6114-8.

- Taylor, John (2005). The Rivalry: Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain, and the Golden Age of Basketball. New York City: Random House. pp. 108–111. ISBN 1-4000-6114-8.

- "1957 NBA Playoffs". Basketball-Reference. Retrieved December 4, 2006.

- "Pettit Drops 50 on Celtics in Game 6". National Basketball Association. Turner Sports Interactive. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- "1959 NBA Playoffs". Basketball-Reference. Retrieved December 4, 2006.

- "Wilt Chamberlain Bio". National Basketball Association. Turner Sports Interactive. Archived from the original on December 15, 2006. Retrieved December 1, 2006.

- Taylor, John (2005). The Rivalry: Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain, and the Golden Age of Basketball. New York City: Random House. pp. 3–10. ISBN 1-4000-6114-8.

- "Syracuse Nationals at Boston Celtics Box Score, February 5, 1960". Basketball-Reference. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- "1960 NBA Finals". Basketball-Reference. Retrieved December 4, 2006.

- "Celtics Give Sharman Championship Sendoff". National Basketball Association. Turner Sports Interactive. Archived from the original on June 10, 2008. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- "1961 NBA Playoffs". Basketball-Reference. Retrieved December 4, 2006.

- "Boston Celtics at Los Angeles Lakers Box Score, April 16, 1962". Basketball-Reference. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- Taylor, John (2005). The Rivalry: Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain, and the Golden Age of Basketball. New York City: Random House. pp. 167–170. ISBN 1-4000-6114-8.

- "1962 NBA Playoffs". Basketball-Reference. Retrieved December 6, 2006.

- "New York Knicks at Boston Celtics Box Score, February 10, 1963". Basketball-Reference. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- "Boston Celtics Players to have recorded a triple-double". Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- "1963 NBA Playoffs". Basketball-Reference. Archived from the original on September 21, 2006. Retrieved December 4, 2006.

- "1964 NBA Playoffs". Basketball-Reference. Archived from the original on September 18, 2006. Retrieved December 4, 2006.