Bluebeard

"Bluebeard" (French: Barbe bleue, [baʁbə blø]) is a French folktale, the most famous surviving version of which was written by Charles Perrault and first published by Barbin in Paris in 1697 in Histoires ou contes du temps passé.[1][2] The tale tells the story of a wealthy man in the habit of murdering his wives and the attempts of one wife to avoid the fate of her predecessors. "The White Dove", "The Robber Bridegroom" and "Fitcher's Bird" (also called "Fowler's Fowl") are tales similar to "Bluebeard".[3][4] The notoriety of the tale is such that Merriam-Webster gives the word "Bluebeard" the definition of "a man who marries and kills one wife after another," and the verb "bluebearding" has even appeared as a way to describe the crime of either killing a series of women, or seducing and abandoning a series of women.[5]

| Bluebeard | |

|---|---|

.png.webp) Bluebeard gives his wife the keys to his castle. | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | Bluebeard |

| Also known as | Barbebleue |

| Data | |

| Aarne-Thompson grouping | ATU 312 (The Bluebeard, The Maiden-Killer) |

| Region | France |

| Published in | Histoires ou contes du temps passé, by Charles Perrault |

| Related | The Robber Bridegroom; How the Devil Married Three Sisters; Fitcher's Bird |

Plot

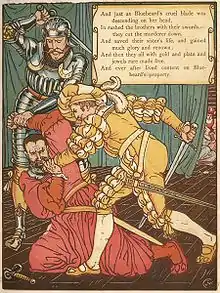

.jpg.webp)

In one version of the story, Bluebeard is a wealthy and powerful nobleman who has been married several times to beautiful women who have all mysteriously vanished. When Bluebeard visits his neighbor and asks to marry one of his daughters, the girls are terrified. After hosting a wonderful banquet, the youngest daughter decides to be his wife and she goes to live with him in his rich and luxurious palace in the countryside, away from her family.

Bluebeard announces that he must leave for the country and gives the keys of the château to his wife. She is able to open any door in the house with them, each of which contain some of his riches, except for an underground chamber that he strictly forbids her to enter lest she suffer his wrath. He then goes away and leaves the house and the keys in her hands. She invites her sister, Anne, and her friends and cousins over for a party. However, she is eventually overcome with the desire to see what the forbidden room holds, and she sneaks away from the party and ventures into the room.

She immediately discovers the room is flooded with blood and the murdered corpses of Bluebeard's former wives hanging on hooks from the walls. Horrified, she drops the key in the blood and flees the room. She tries to wash the blood from the key, but the key is magical and the blood cannot be removed. Bluebeard unexpectedly returns and finds the bloody key. In a blind rage, he threatens to kill his wife on the spot, but she asks for one last prayer with her sister Anne. Then, as Bluebeard is about to deliver the fatal blow, Anne and the wife's brothers arrive and kill Bluebeard. The wife inherits his fortune and castle, and has the dead wives buried. She uses the fortune to have her other siblings married then remarries herself, finally moving on from her horrible experience with Bluebeard.[6]

Sources

Although best known as a folktale, the character of Bluebeard appears to derive from legends related to historical individuals in Brittany. One source is believed to have been the 15th-century convicted Breton serial killer Gilles de Rais, a nobleman who fought alongside Joan of Arc and became both Marshal of France and her official protector, then was hanged and burned as a murderous witch.[7] However, Gilles de Rais did not kill his wife, nor were any bodies found on his property, and the crimes for which he was convicted involved the sexually-driven, brutal murder of children rather than women.[8]

Another possible source stems from the story of the early Breton king Conomor the Accursed and his wife Tryphine. This is recorded in a biography of St. Gildas, written five centuries after his death in the sixth century. It describes how after Conomor married Tryphine, she was warned by the ghosts of his previous wives that he murders them when they become pregnant. Pregnant, she flees; he catches and beheads her, but St. Gildas miraculously restores her to life, and when he brings her to Conomor, the walls of his castle collapse and kill him. Conomor is a historical figure, known locally as a werewolf, and various local churches are dedicated to Saint Tryphine and her son, Saint Tremeur.[9]

Commentaries

_(14592970659).jpg.webp)

The fatal effects of female curiosity have long been the subject of story and legend. Eve, Lot's wife, Pandora, and Psyche are all examples of women in mythic stories whose curiosity is punished by dire consequences. In giving his wife the keys to his castle, Bluebeard is acting the part of the serpent, and therefore of the devil, and his wife the part of the victim held by the serpent's gaze.[10]

In addition, hidden or forbidden chambers were not unknown in pre-Perrault literature. In Basile's Pentamerone, the tale The Three Crowns tells of a Princess Marchetta entering a room after being forbidden by an ogress, and in The Arabian Nights, Prince Agib is given a hundred keys to a hundred doors but forbidden to enter the golden door, which he does with terrible consequences.[11]

While some scholars interpret the Bluebeard story as a fable preaching obedience to wives (as Perrault's moral suggests), folklorist Maria Tatar has suggested that the tale encourages women not to unquestioningly follow patriarchal rules. Women breaking men's rules in the fairy tale can be seen as a metaphor for women breaking society's rules and being punished for their transgression.[12] The key can be seen as a sign of disobedience or transgression; it can also be seen as a sign that one should not trust their husband.[13]

Tatar, however, does go on to speak of Bluebeard as something of a "Beauty and the Beast" narrative. The original Beauty and the Beast tale by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont is said to be a story created to condition young women into the possibility of not only marriage, but marrying young, and to placate their fears of the implications of an older husband.[14] It shows the beast as secretly compassionate, and someone meant to curb the aggressive sexual fears that young women have towards marriage. Though "Beauty and the Beast" holds several similarities in Gothic imagery to "Bluebeard,"(such as is shared with Cupid and Psyche as well, in the case of a mysterious captor, a looming castle, and a young, beautiful heroine) Tatar goes on to state that the latter tale lives on the entire opposite side of the spectrum: one in which, instead of female placation, the tale simply aggravates women's apprehension, confirming one's "'worst fears about sex'".[15]

Jungian psychoanalyst Clarissa Pinkola Estés refers to the key as the key of knowing which gives the wife consciousness. She can choose to not open the door and live as a naive young woman. Instead, she has chosen to open the door of truth.[16]

For folklorist Bruno Bettelheim, Bluebeard can only be considered a fairy tale because of the magical bleeding key; otherwise, it would just be a monstrous horror story. Bettelheim sees the key as associated with the male sexual organ, "particularly the first intercourse when the hymen is broken and blood gets on it." For Bettelheim, the blood on the key is a symbol of the wife's indiscretion.[17]

For scholar Philip Lewis, the key offered to the wife by Bluebeard represents his superiority, since he knows something she does not. The blood on the key indicates that she now has knowledge. She has erased the difference between them, and in order to return her to her previous state, he must kill her.[18][19]

Aarne–Thompson classification

According to the Aarne–Thompson system of classifying folktale plots, the tale of Bluebeard is type 312.[20] Another such tale is The White Dove, an oral French variant.[21] The type is closely related to Aarne–Thompson type 311 in which the heroine rescues herself and her sisters, in such tales as Fitcher's Bird, The Old Dame and Her Hen, and How the Devil Married Three Sisters. The tales where the youngest daughter rescues herself and the other sisters from the villain is in fact far more common in oral traditions than this type, where the heroine's brother rescues her. Other such tales do exist, however; the brother is sometimes aided in the rescue by marvelous dogs or wild animals.[22]

Some European variants of the ballad Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight, Child ballad 4, closely resemble this tale. This is particularly noteworthy among some German variants, where the heroine calls for help much like Sister Anne calls for help to her brothers in Perrault's Bluebeard.[23]

Bluebeard's wives

It is not explained why Bluebeard murdered his first bride; she could not have entered the forbidden room and found a dead wife. Some scholars have theorized that he was testing his wife's obedience, and that she was killed not for what she discovered there, but because she disobeyed his orders.[24]

In the 1812 version published in Grimms' Fairy Tales, Wilhelm Grimm, on p. XLI of the annotations, makes the following handwritten comment: "It seems in all Märchen [fairy tales] of Bluebeard, wherein his Blutrunst [lust for blood] has not rightly explained, the idea to be the basis of himself through bathing in blood to cure of the blue beard; as the lepers. That is also why it is written that the blood is collected in basins."

Maurice Maeterlinck wrote extensively on Bluebeard and in his plays name at least six former wives: Sélysette from Aglavaine et Sélysette (1896), Alladine from Alladine et Palomides (1894), both Ygraine and Bellangère from La mort de Tintagiles (1894), Mélisande from Pelléas et Mélisande, and Ariane from Ariane et Barbe-bleue (1907).

In Jacques Offenbach's opera Barbe-bleue (1866), the five previous wives are Héloïse, Eléonore, Isaure, Rosalinde and Blanche, with the sixth and final wife being a peasant girl, Boulotte, who finally reveals his secret when he attempts to have her killed so that he can marry Princess Hermia.

Béla Bartók's opera Bluebeard's Castle (1911), with a libretto by Béla Balázs, names "Judith" as wife number four.

Anatole France's short story "The Seven Wives of Bluebeard" names Jeanne de Lespoisse as the last wife before Bluebeard's death. The other wives were Collette Passage, Jeanne de la Cloche, Gigonne, Blanche de Gibeaumex, Angèle de la Garandine, and Alix de Pontalcin.

In Edward Dmytryk's film Bluebeard (1972), Baron von Sepper (Richard Burton) is an Austrian aristocrat known as Bluebeard for his blue-toned beard and his appetite for beautiful wives, and his wife is an American named Anne.

Variants

- "Bluebeard", a fairy tale (KHM 62a, dropped from later editions) collected by The Brothers Grimm in Kinder- und Hausmärchen (KHM) (1812)[25]

- "The Robber Bridegroom", a variant (KHM 40) in Grimms' Fairy Tales (1812)[26]

- "Fitcher's Bird", another variant (KHM 48) in Grimms' Fairy Tales (1812)[27]

- "The Castle of Murder" (KHM 73a, dropped from later editions), another variant in Grimms' Fairy Tales (1812)

- "Mr. Fox", an English variant of Bluebeard[28]

- "The White Dove" a French variant of Bluebeard[4]

Versions and reworkings

Literature

.png.webp)

Other versions of Bluebeard include:[29][30]

- Commentaires Apostoliques et Théologiques sur les Saintes Prophéties de l"auteur Sacré de Barbe-Bleue, (1779), a satire by Frederick the Great

- Die Sieben Weiber des Blaubart (The Seven Wives of Bluebeard) (1797), a novel by Ludwig Tieck

- "Blaubart (Bluebeard)" (1850), a fairy tale by Alexander von Ungern-Sternberg[31]

- "Captain Murderer" (1860), a short story by Charles Dickens [32]

- "Le Sixième Mariage de Barbe-Bleue ("Bluebeard's Sixth Marriage") (1892), a short story by Henri de Régnier

- "Bluebeard's Keys" (1902), a short story by Anne Thackeray Ritchie

- "The Seven Wives of Bluebeard" (1903), a short story by Anatole France

- Chevalier Blaubarts Liebesgarten (Knight Bluebeard's Love Garden) (1910), a novel by Joseph August Lux

- Ritter Blaubart ("Bluebeard the Knight") (1911), a short story by Alfred Döblin

- Sister Anne (1932), a novella by Beatrix Potter

- The Robber Bridegroom (1942), a novella by Eudora Welty

- "The Bloody Chamber" (1979), a short story by Angela Carter[33]

- Bluebeard (1982), a novel by Max Frisch[34]

- "Bluebeard's Egg" (1983), a short story by Margaret Atwood in a collection of the same name [35]

- Blaubarts Letzte Reise ("Bluebeard's Last Trip"), (1983), a short story by Peter Rühmkorf

- "Bluebeard", (1986), a short story by Donald Barthelme

- Bluebeard (1987), a Kurt Vonnegut novel[36]

- "Blue-Bearded Lover" (1987), a short story by Joyce Carol Oates[37]

- Blaubarts Schatten (Bluebeard's Ghost) (1991), a novel by Karin Struck

- "Bluebeard in Ireland"' (1994), a short story by John Updike[38]

- Fitcher's Brides (2002), a novel by Gregory Frost[39]

- Barbe-Bleue (Bluebeard) (2012), a novel by Amélie Nothomb

- Mr. Fox (2011), a novel by Helen Oyeyemi

In Charles Dickens' short story "Captain Murderer", the titular character is described as "an offshoot of the Bluebeard family", and is far more bloodthirsty than most Bluebeards: he cannibalises each wife a month after marriage. He meets his demise after his sister-in-law, in revenge for the death of her sister, marries him and consumes a deadly poison just before he devours her.[40]

In Anatole France's The Seven Wives of Bluebeard, Bluebeard is the victim of the tale, and his wives the perpetrators. Bluebeard is a generous, kind-hearted, wealthy nobleman called Bertrand de Montragoux who marries a succession of grotesque, adulterous, difficult, or simple-minded wives. His first six wives all die, flee, or are sent away under unfortunate circumstances, none of which are his fault. His seventh wife deceives him with another lover and murders him for his wealth.[41]

In Angela Carter's "The Bloody Chamber", Bluebeard is a 1920s decadent with a collection of erotic drawings, and Bluebeard's's wife is rescued by her mother, who rides in on a horse and shoots Bluebeard between the eyes, rather than by her brothers as in the original fairy tale.[33]

In Joyce Carol Oates' short story, "Blue-Bearded Lover", the most recent wife is well aware of Bluebeard's murdered wives: she does not unlock the door to the forbidden room, and therefore avoids death herself. She remains with Bluebeard despite knowing he is a murderer, and gives birth to Bluebeard's children. The book has been interpreted as a feminist struggle for sexual power.[42]

In Helen Oyeyemi's Mr. Fox, Mr. Fox is a writer of slasher novels, with a muse named Mary. Mary questions Mr. Fox about why he writes about killing women who have transgressed patriarchal laws, making him aware of how his words normalize domestic violence. One of the stories in the book is about a girl named Mary who has a fear of serial killers because her father raised her on stories about men who killed women who didn't obey them and then killed her mother.[43]

Kurt Vonnegut's Bluebeard features a painter who calls himself Bluebeard, and who considers his art studio to be a forbidden chamber where his girlfriend Circe Berman is not allowed to go.[44]

In Donald Barthelme's Bluebeard, the wife believes that the carcasses of Bluebeard's previous six wives are behind the door. She loses the key and her lover hides the three duplicates. One afternoon Bluebeard insists that she open the door, so she borrows his key. Inside, she finds the decaying carcasses of six zebras dressed in Coco Chanel gowns.[45]

In theatre

- Pantomime versions of the tale were staged at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in London as early as 1798, and famous editions there were by E. L. Blanchard in 1879 and starred Dan Leno in 1901.[46] Many of these productions orientalized the tale by setting it in the Ottoman Empire, often giving the wife the name Fatima. The popularity of the pantomime made orientalized depictions of Bluebeard common in English illustrations throughout the 19th century and into the early 20th century.

- Ariane et Barbe-bleue (1899), a symbolist play by Maurice Maeterlinck

- Bluebeard's Eighth Wife (1921), a French farce by Alfred Savoir

- Bluebeard (1896), a ballet by choreographer Marius Petipa to the music of composer Pyotr Schenk.[47]

- Bluebeard (2015), a ballet based on the novel The Seven Wives of Bluebeard by Anatole France, directed and choreographed by Staša Zurovac and composed by Marjan Nećak

- Bluebeard (1970), an off-Broadway absurdist comedy by Charles Ludlam, adapted from The Island of Dr Moreau

- Ritter Blaubart (Knight Bluebeard) (1797), a play by Ludwig Tieck

- The Grand Dramatic Romance Bluebeard, or Female Curiosity, a 1798 play by George Colman the Younger

- Blaubart: Drama giocoso (1985), a play by Martin Mosebach

- Bluebeard (1895), a ballet by Georges Jacobi, choreographed by Carlo Coppi

- Bluebeard (1941), by Jacques Offenbach, choreographed by Michel Fokine

- Blaubarts Traum (Bluebeard's Dream) (1961), a ballet by Harold Saeverud, choreographed by Yvonne Georgi

- Bluebeard's Friends (2019), one of three short plays by Caryl Churchill

In music

- Raoul Barbe-bleue (1789), an opera by André Grétry

- Barbe-bleue (1866), an operetta by Jacques Offenbach

- Ariane et Barbe-bleue (1907), an opera by Paul Dukas

- Bluebeard's Castle (1918), an opera by Béla Bartók and Béla Balázs

- "Bluebeard" (1993), a song by the Cocteau Twins, on the album Four-Calendar Café

- "Go Long" by Joanna Newsom (2010), on the album Have One on Me[48]

- "Aoki Hakushaku no Shiro" (English Translation: "The Blue Marquis' Castle"), a song by Sound Horizon, on the album Märchen (album)

- "Mrs. Bluebeard", a song by They Might Be Giants, on the album I Like Fun

- "Bluebeard" (2019) a song by Patty Griffin, on the album Patty Griffin

- "Nightmares by the Sea", a song by Jeff Buckley, on the album Sketches for My Sweetheart the Drunk

In film

Several film versions of the story were made:

- Barbe-bleue, a 1901 short film by Georges Méliès

- Bluebeard's 8th Wife, a 1923 silent comedy film directed by Sam Wood and starring Gloria Swanson

- Bluebeard's Eighth Wife, a 1938 remake of the Swanson silent, directed by Ernst Lubitsch and starring Claudette Colbert and Gary Cooper

- Bluebeard, a 1944 film directed by Edgar G. Ulmer, starring John Carradine

- Secret Beyond the Door, a 1948 contemporary adaptation directed by Fritz Lang, starring Michael Redgrave and Joan Bennett

- Bluebeard's Six Wives, a 1950 Italian comedy film directed by Carlo Ludovico Bragaglia, starring Totò

- Barbe-Bleue, (titled Bluebeard in the U.S.), a 1951 German-French film directed by Christian-Jaque, starring Hans Albers

- Bluebeard, a 1972 film directed by Edward Dmytryk, starring Richard Burton, Joey Heatherton, Raquel Welch, and Virna Lisi

- Barbe Bleue, a 2009 film directed by Catherine Breillat [49]

- Monsieur Verdoux, a 1947 black comedy film directed by and starring Charles Chaplin

- Bluebeard's Ten Honeymoons, a 1960 British thriller directed by W. Lee Wilder and starring George Sanders

- Landru (titled Bluebeard in the U.S.), a 1963 French drama directed by Claude Chabrol starring Charles Denner, Michèle Morgan, and Danielle Darrieux

- Herzog Blaubarts Burg (Duke Bluebeard's Castle), a 1963 film directed by Michael Powell, a film of the Béla Bartók opera Bluebeard's Castle

- Miss Bluebeard, a 1925 silent comedy film directed by Frank Tuttle and starring Bebe Daniels, based on the play Little Miss Bluebeard

- Barbe-bleue, a 1936 claymation short film directed by Jean Painlevé

- La Barbe-bleue, a 1986 French TV movie adaptation directed by Alain Ferrari

- Juliette, or Key of Dreams, a 1951 French film based on the 1930 play of the same name, in which a main character is directly inspired from Bluebeard

- The Piano, a 1993 film directed by Jane Campion, a loose adaptation which features a Christmas pageant presentation of the fairy tale Bluebeard.

- Gaslight, Rebecca, and Suspicion are Classical Hollywood cinema variations on the Bluebeard tale.[50][51]

- Ochen' siniya boroda (Very Blue Beard), a 1979 Soviet animated film, gives modern satirical variations on the theme of Bluebeard

- Ex Machina, a 2015 film directed by Alex Garland, adapts the Bluebeard character as the reclusive CEO of a fictional tech company called "Bluebook"

- Crimson Peak, a 2015 Gothic horror film, has plot similarities to the tale of Bluebeard in that a woman is taken to her husband's castle where he hides a dark, forbidden secret.

- Elizabeth Harvest, a 2018 film directed by Sebastian Gutierrez, taking a modern approach to the tale.

- Bye, Bye Bluebeard is a 1949 Warner Brothers cartoon by Arthur Davis in which Bluebeard is portrayed as a blue bearded wolf/a killer on the loose who appears at the home of Porky Pig.

In poetry

- "Bluebeard's Closet" (1888), a poem by Rose Terry Cooke[52]

- "Der Ritter Blaubart" (The Knight Bluebeard) (1911), a poem by Reinhard Koester

- "I Seek Another Place" (1917), a sonnet by Edna St. Vincent Millay.[53]

- "Bluebeard", a poem by Sylvia Plath[54]

- The story is alluded to in Seamus Heaney's 1966 poem "Blackberry Picking":[55]"Our hands were peppered/With thorn pricks, our palms sticky as Bluebeard's."

References in literature

- In Charlotte Brontë's 1847 novel Jane Eyre, the narrator alludes to her husband as Bluebeard, and to his castle as Bluebeard's castle.[56]

- In Machado de Assis’s story "The Looking Glass," the main character, Jacobina, dreams he is trying to escape Bluebeard.

- In The Scarlet Pimpernel by Baroness Orczy, the story of Bluebeard is referred to in Chapter 18, with Sir Percy's bedroom being compared to Bluebeard's chamber, and Marguerite to Bluebeard's wife.[57]

- In William Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing, the character Benedick exclaims, "Like the old tale, my lord: "It is not so nor 'twas not so but, indeed, God forbid it should be so." Here Benedick is quoting a phrase from an English variant of Bluebeard, Mr. Fox,[58] referring to it as "the old tale."

- In The Blue Castle, a 1926 novel by Lucy Maude Montgomery, Valancy's mysterious new husband forbids her to open one door in his house, a room they both term "Bluebeard's Chamber."

- In Stephen King's The Shining, the character Jack Torrance reads the story of Bluebeard to his three-year-old son Danny, to his wife's disapproval. The Shining also directly references the Bluebeard tale in that there is a secret hotel room which conceals a suicide, a remote castle (The Overlook Hotel), and a husband (Jack) who attempts to kill his wife.

- In Fifty Shades of Grey by E. L. James, Mr. Grey has a bloody S & M chamber where he tortures Anastasia, and she refers to him at least once as Bluebeard.[59]

- "Bones'"a short story by Francesca Lia Block, recasts Bluebeard as a sinister L.A. promoter.[60]

- The short story Trenzas ("Braids") by Chilean writer María Luisa Bombal has some paragraphs where the narrator comments on Bluebeard's last wife having long and thick braids that would get tangled in Bluebeard's fingers, and as he struggled to undo them before killing her, he was caught and killed by the woman's protective brothers.[61]

In television

- In a 1977 episode of Lou Grant, when considering their employer Mrs. Pynchon's relationship with a media mogul, Lou Grant says to Charlie Hume, "They make a nice couple." Whereupon, Charlie responds : "How often do you think that was mentioned at Bluebeard's wedding?"[62]

- Bluebeard is featured in Grimm's Fairy Tale Classics as part of its "Grimm Masterpiece Theater" season. The bride is the peasant teenage girl Josephine, raised by her three woodworker brothers; she is deliberately chosen by Bluebeard for her beauty, her naivete and her desire to marry a prince. The character design for Bluebeard strongly resembles the English King Henry VIII.

- Bluebeard is featured in Sandra the Fairytale Detective as the villain in the episode "The Forbidden Room".

- Bluebeard is featured in Scary Tales, produced by the Discovery Channel, Sony and IMAX, episode one, in 2011. (This series is not related to the Disney collection of the same name.)

- Bluebeard was the subject of the pilot episode of an aborted television series, Famous Tales (1951), created by and starring Burl Ives with music by Albert Hague.

- A Korean stage play of the Bluebeard story serves as the backstory and inspiration for the antagonist, a serial kidnapper, in the South Korean television show, Strong Woman Do Bong-soon (2017).

- Hannibal (TV series), Season 3 episode 12 "The Number of the Beast is 666", Bedelia Du Maurier compares herself and the protagonist Will Graham to Bluebeard's brides, referring to their relationships with Hannibal Lecter.

- You (TV series), Season 1 episode 10 "Bluebeard's Castle", along with taking the episodes namesake from the fairy tale, heroine Guinevere Beck compares the character Joe Goldberg to Bluebeard and his glass box to Bluebeard's Castle.[63]

- It's Okay to Not Be Okay is a South Korean Drama in which this tale is narrated in episode 6.

- The TV series Grimm; episode 4, season 1,"Lonely Hearts", is based on Bluebeard. The antagonist is a serial rapist who keeps all of his (living) victims in a secret basement room.

In other media

- The fairy tale of Bluebeard was the inspiration for the Gothic feminine horror game Bluebeard's Bride by Whitney "Strix" Beltrán, Marissa Kelly, and Sarah Richardson. Players play from the shared perspective of the Bride, each taking on an aspect of her psyche.[64]

- In DC Comics' Fables series, Bluebeard appears as an amoral character, willing to kill and often suspected of being involved in various nefarious deeds.

- Bluebeard is a character in the video game by Telltale Games based on the Fables comics The Wolf Among Us.

- In the Japanese light novel and manga/anime Fate/Zero, Bluebeard appears as the Caster Servant, where his character largely stems from Gilles de Rais as a serial murderer of children.

- The Awful History of Bluebeard consists of 7 original drawings by William Makepeace Thackeray from 1833, given as a gift to his cousin on her 11th birthday and published in 1924.[65]

- A series of photographs published in 1992 by Cindy Sherman illustrate the fairy tale Fitcher's Bird (a variant of Bluebeard).

- Bluebeard appears as a minor darklord in the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (2nd ed.) Ravenloft Accessory Darklords.[66]

- BBC Radio 4 aired a radio play from 2014 called Burning Desires written by Colin Bytheway, about the serial killer Landru, an early 20th-century Bluebeard.[67]

- The 2013 fantasy horror comic Porcelain: A Gothic Fairy Tale (by Benjamin Read and Chris Wildgoose) employs the Bluebeard story element with the bloody key to a secret room of horrors.[68]

- The 1955 film The Night of the Hunter includes a scene at the trial of serial wife killer in which the crowd/mob chants "Bluebeard!" repeatedly.

- A mausoleum containing the remains of Bluebeard and his wives can be seen at the exit of The Haunted Mansion at Walt Disney World.

- The card "Malevolent Noble" in the Throne of Eldraine expansion of Magic: The Gathering is a visual reference to Bluebeard.

- The independent role playing game Bluebeard's Bride by Magpie Games is centered around the premise of the fairy tale with players acting out emotions and thoughts of the titular bride.[69]

- The tale inspired the plot of hidden object game Dark Romance 5: Curse of Bluebeard, by developer DominiGames.

- Ceramic tiles tell the tale of Bluebeard and his wives in Fonthill Castle, the home of Henry Mercer in Doylestown, PA.

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- "Charles Perrault (1628–1703)". CLPAV.

- "Bluebeard, The Robber Bridegroom, and Ditcher's Bird". JML: Grimm to Disney.

- "The White Dove: A French Bluebeard". Tales of Faerie.

- "Words We're Watching: 'Bluebeard,' the Verb". Merriam-Webster.

- Perrault, Charles. "Bluebeard". Childhood Reading.com.

- Margaret Alice Murray (1921). The Witch-cult in Western Europe: A Study in Anthropology. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 267. ISBN 0-19-820744-1.

- Paoletti, Gabe. "Gilles De Rais, The Child Serial Killer Who Fought Alongside Joan Of Arc". All That is Interesting.com.

- Warner, Marina (1995). From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales And Their Tellers. p. 261. ISBN 0-374-15901-7.

- Bridgewater, Patrick (2013). The German Gothic Novel in Anglo-German Perspective. Rodopi. p. 238.

- "The History of Agib". More Fairy Tales From The Arabian Nights.

- Jónsdóttir, Margrét Snæfríður. "Madam Has a Word to Say" (PDF). Skemann.is.

- Tatar, Maria (2002). "The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales". New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Tatar, Maria (2017). Beauty and the Beast: Classic Tales About Animal Brides and Grooms from Around the World. New York: Penguin Books. p. 190. ISBN 978-0143111696.

- Tatar, Maria (2004). Secrets Beyond the Door: The Story of Bluebeard and His Wives. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 247. ISBN 0-691-11707-1.

- Estés, Clarissa Pinkola (1995). "Women who Run with the Wolves". New York: Ballantine Books.

- Bettelheim, Bruno (1977). The Uses of Enchantment. New York: Vintage Books.

- Hermansson, Casie (2009). Bluebeard. A reader's Guide to the English Tradition. Minnesota: University of Mississippi: Association of American University Presses.

- Lewis, Philip E. (1996). Seeing through the Mother Goose tales : visual turns in the writings of Charles Perrault. California: Stanford University Press.

- Heidi Anne Heiner. "Tales Similar to Bluebeard". SurLaLune Fairy Tales.

- Paul Delarue (1956). The Borzoi Book of French Folk-Tales, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., p. 359

- Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. p. 36.

- Francis James Child (1965). The English and Scottish Popular Ballads; v. 1, New York: Dover Publications, p. 47

- Lewis, Philip (1996). Seeing Through the Mother Goose Tales. Stanford University Press.

- The Gale Group. "Bluebeard (Blaubart) By Jacob And Wilhelm Grimm, 1812". Encyclopedia.com.

- Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm. "The Robber Bridegroom". Pitt.edu.

- Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm. "Fitcher's Bird". Pitt.edu.

- "Mr. Fox (an English tale)". Sur La Lune Fairy Tales.com. Archived from the original on 2018-07-20. Retrieved 2018-06-13.

- Shuli Barzilai, Tales of Bluebeard and His Wives from Late Antiquity to Postmodern Times

- Hermansson, Casie (2009). Bluebeard: A Reader's Guide to the English Tradition. University of Mississippi.

- Ungern-Sternberg, Alexander von. "Blaubart". Spiegel Online.

- Dickens, Charles. "Captain Murderer". charlesdickenspage.com.

- Acocella, Joan. "Angela Carter's Feminist Mythology". The New Yorker.

- Gilman, Richard. "Who Killed Wife No. 6?". The New York Times.

- Towers, Robert. "Old-Fashioned Virtues, Bohemian Vices". The New York Times.

- Moynahan, Julian. "A Prisoner of War in the Hamptons". The New York Times.

- Oates, Joyce Carol. "Blue-bearded lover". indbooks.ind.

- Updike, John. "Bluebeard in Ireland". indbooks.ind.

- Millard, Martha. "Fitcher's Brides". Publisher's Weekly.

- Dickens, Charles. "Captain Murderer". The Robber Bridegroom and other folktales of Aarne-Thompson-Uther type 955.

- France, Anatole. "The Seven Wives of Bluebeard". Gutenberg.org.

- Freeman-Slade, Jessica. "Once Children". Los Angeles Review of Books.

- Bender, Aimee. "A Writer of Slasher Books Finds More Than a Muse". The New York Times.

- Moynahan, Julian. "A Prisoner of War in the Hamptons". The New York Times.

- Barthelme, Donald. "Bluebeard". The New Yorker.

- Adams, William Davenport. "A dictionary of the drama: a guide to the plays, play-wrights, players, and playhouses of the United Kingdom and America", Chatto & Windus, 1904, p. 176

- "Bluebeard". The Marius Petipa Society.

- Newsom, Joanna. "Go Long". Genius.com.

- Hohenadel, Kristin. "Fairy-Tale Endings: Death by Husband". The New York Times.

- Lurie, Alison. "One Bad Husband". The American Scholar.

- Biller, Anna. "Bluebeard at the Movies". Talkhouse.

- Cooke, Rose Terry. "Blue-Beard's Closet". Bartleby.com.

- Millay, Edna St. Vincent. "Bluebeard". Poemhunter.

- Plath, Sylvia. "Bluebeard". Poemhunter.

- Heaney, Seamus. "Blackberry-Picking". Poetry Foundation.

- Troiano, Ali. "Jane Eyre and "Bluebeard"". English Novel Writing.

- Orczy, Emma. "Chapter 18 – The Mysterious Device". Scarlet Pimpernel.com. Archived from the original on 2018-05-20. Retrieved 2018-06-13.

- Folk Tale, English. "Mr. Fox". World of Tales.

- Biller, Anna. "Fifty Shades of Grey is a Bluebeard Story". Anna Biller's Blog.

- "The Rose and the Beast". Kirkus Reviews.

- https://albalearning.com/audiolibros/bombal/trenzas.html

- "Lou Grant: Episode "Takeover"". IMDB.

- "You: Episode 'Bluebeard's Castle'". IMDB.

- Boss, Emily Care. "Bluebeard's Bride and Noir Themes – Interview with Strix Beltrán, Sarah Richardson and Marissa Kelly". Black and Green Games.

- Thackeray, William Makepeace. "The Awful History of Bluebeard: Original Drawings". Archive.org.

- Lucard, Alex. "Tabletop Review: Ravenloft: Darklords (Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition)". Diehard Game Fan.com.

- Bytheway, Colin. "Burning Desires". BBC.

- "Interview with Benjamin Read and Chris Wildgoose". Geek Pride.

- "Bluebeard's Bride". Magpie Games.

Further reading

- Apostolidès, Jean-Marie. "DES CHOSES CACHÉES DANS LE CHÂTEAU DE BARBE BLEUE." Merveilles & Contes, vol. 5, no. 2, 1991, pp. 179–199. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41390294. Accessed 30 Apr. 2020.

- Barzilai, Shuli. Tales of Bluebeard and His Wives from Late Antiquity to Postmodern Times. London: Routledge, 2009. Print.

- Da Silva, Francisco Vaz. Marvels & Tales, vol. 24, no. 2, 2010, pp. 358–360. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41388968. Accessed 30 Apr. 2020.

- Estés, Clarissa P. (1992). Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype. New York: Random House, Inc.

- Hermansson, Casie E. (2009). Bluebeard: A Reader's Guide to the English Tradition. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi.

- Loo, Oliver (2014). The Original 1812 Grimm Fairy Tales Kinder- und Hausmärchen Children's and Household Tales.

- Lovell-Smith, Rose. "Anti-Housewives and Ogres' Housekeepers: The Roles of Bluebeard's Female Helper." Folklore, vol. 113, no. 2, 2002, pp. 197–214. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1260676. Accessed 30 Apr. 2020.

- Lurie, Alison. "One Bad Husband: What the ‘Bluebeard’ Story Tells Us about Marriage." The American Scholar, vol. 74, no. 1, 2005, pp. 129–132. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41221385. Accessed 30 Apr. 2020.

- Ruddick, Nicholas. "‘Not So Very Blue, after All’: Resisting the Temptation to Correct Charles Perrault's ‘Bluebeard.’" Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts, vol. 15, no. 4 (60), 2004, pp. 346–357. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43308720. Accessed 30 Apr. 2020.

- Sumpter, Caroline. "Tales of Bluebeard and His Wives from Late Antiquity to Postmodern Times, by Shuli Barzilai." Victorian Studies, vol. 55, no. 1, 2012, pp. 160–162. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/victorianstudies.55.1.160. Accessed 30 Apr. 2020.

- Tatar, Maria (2004). Secrets Beyond the Door: The Story of Bluebeard and His Wives. Princeton / Oxford, Princeton University Press.

- Vizetelly, Ernest Alfred (1902). Bluebeard: An Account of Comorre the Cursed and Gilles de Rais, with Summaries of Various Tales and Traditions; Chatto & Windus; Westminster, England.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bluebeard. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Look up Bluebeard in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- SurLaLune Fairy Tale Pages: Heidi Anne Heiner, "The Annotated Bluebeard"

- Variants

- "Bluebeard and the Bloody Chamber" by Terri Windling

- Leon Botstein's concert notes on Dukas' Ariane et Barbe-bleue

- Glimmerglass Opera's notes on Offenbach's Barbe Bleue, the Bluebeard fairy tale in general, and operetta in the time of Offenbach.

- A Shakespeare reference

- Bluebeard, audio version

(in French)

(in French)