Puss in Boots

"Master Cat, or The Booted Cat" (Italian: Il gatto con gli stivali; French: Le Maître chat ou le Chat botté), commonly known in English as "Puss in Boots", is an Italian[1][2] and later European literary fairy tale about an anthropomorphic cat who uses trickery and deceit to gain power, wealth, and the hand of a princess in marriage for his penniless and low-born master.

| "Puss in Boots" | |

|---|---|

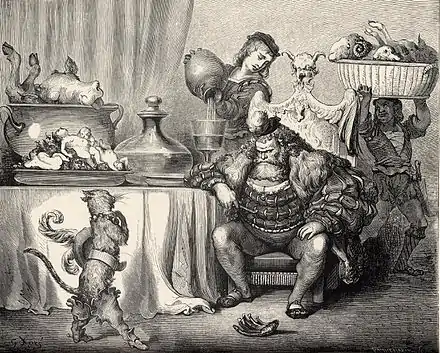

_-_Le_Chat_bott%C3%A9_-_1.png.webp) Illustration 1843, from édition L. Curmer | |

| Author | Giovanni Francesco Straparola Giambattista Basile Charles Perrault |

| Country | Italy (1550–1553) France (1697) |

| Language | Italian (originally) |

| Genre(s) | Literary fairy tale |

| Publication type | Fairy tale collection |

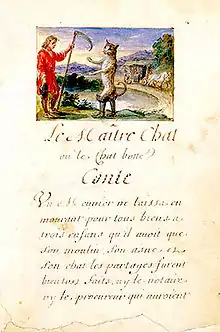

The oldest telling is by Italian author Giovanni Francesco Straparola, who included it in his The Facetious Nights of Straparola (c. 1550–1553) in XIV–XV. Another version was published in 1634 by Giambattista Basile with the title Cagliuso, and a tale was written in French at the close of the seventeenth century by Charles Perrault (1628–1703), a retired civil servant and member of the Académie française. There is a version written by Girolamo Morlini, from whom Straparola used various tales in The Facetious Nights of Straparola.[3] The tale appeared in a handwritten and illustrated manuscript two years before its 1697 publication by Barbin in a collection of eight fairy tales by Perrault called Histoires ou contes du temps passé.[4][5] The book was an instant success and remains popular.[3]

Perrault's Histoires has had considerable impact on world culture. The original Italian title of the first edition was Costantino Fortunato, but was later known as Il gatto con gli stivali (lit. The cat with the boots); the French title was "Histoires ou contes du temps passé, avec des moralités" with the subtitle "Les Contes de ma mère l'Oye" ("Stories or Fairy Tales from Past Times with Morals", subtitled "Mother Goose Tales"). The frontispiece to the earliest English editions depicts an old woman telling tales to a group of children beneath a placard inscribed "MOTHER GOOSE'S TALES" and is credited with launching the Mother Goose legend in the English-speaking world.[4]

"Puss in Boots" has provided inspiration for composers, choreographers, and other artists over the centuries. The cat appears in the third act pas de caractère of Tchaikovsky's ballet The Sleeping Beauty,[6] appears in the sequels and self-titled spin-off to the animated film Shrek and is signified in the logo of Japanese anime studio Toei Animation. Puss in Boots is also a popular pantomime in the UK.

Plot

The tale opens with the third and youngest son of a miller receiving his inheritance—a cat. At first, the youngest son laments, as the eldest brother gains the mill, and the middle brother gets the mules. The feline is no ordinary cat, however, but one who requests and receives a pair of boots. Determined to make his master's fortune, the cat bags a rabbit in the forest and presents it to the king as a gift from his master, the fictional Marquis of Carabas. The cat continues making gifts of game to the king for several months, for which he is rewarded.

One day, the king decides to take a drive with his daughter. The cat persuades his master to remove his clothes and enter the river which their carriage passes. The cat disposes of his master's clothing beneath a rock. As the royal coach nears, the cat begins calling for help in great distress. When the king stops to investigate, the cat tells him that his master the Marquis has been bathing in the river and robbed of his clothing. The king has the young man brought from the river, dressed in a splendid suit of clothes, and seated in the coach with his daughter, who falls in love with him at once.

The cat hurries ahead of the coach, ordering the country folk along the road to tell the king that the land belongs to the "Marquis of Carabas", saying that if they do not he will cut them into mincemeat. The cat then happens upon a castle inhabited by an ogre who is capable of transforming himself into a number of creatures. The ogre displays his ability by changing into a lion, frightening the cat, who then tricks the ogre into changing into a mouse. The cat then pounces upon the mouse and devours it. The king arrives at the castle that formerly belonged to the ogre, and, impressed with the bogus Marquis and his estate, gives the lad the princess in marriage. Thereafter, the cat enjoys life as a great lord who runs after mice only for his own amusement.[7]

The tale is followed immediately by two morals: "one stresses the importance of possessing industrie and savoir faire while the other extols the virtues of dress, countenance, and youth to win the heart of a princess."[8] The Italian translation by Carlo Collodi notes that the tale gives useful advice if you happen to be a cat or a Marquis of Carabas.

This is the theme in France, but other versions of this theme exist in Asia, Africa, and South America.[9]

Background

Perrault's "The Master Cat, or Puss in Boots" is the most renowned tale in all of Western folklore of the animal as helper.[10] However, the trickster cat was not Perrault's invention.[11] Centuries before the publication of Perrault's tale, Somadeva, a Kashmir Brahmin, assembled a vast collection of Indian folk tales called Kathā Sarit Sāgara (lit. "The ocean of the streams of stories") that featured stock fairy tale characters and trappings such as invincible swords, vessels that replenish their contents, and helpful animals. In the Panchatantra (lit. "Five Principles"), a collection of Hindu tales from the 2nd century BC., a tale follows a cat who fares much less well than Perrault's Puss as he attempts to make his fortune in a king's palace.[12]

In 1553, "Costantino Fortunato", a tale similar to "Le Maître Chat", was published in Venice in Giovanni Francesco Straparola's Le Piacevoli Notti (lit. The Facetious Nights),[13] the first European storybook to include fairy tales.[14] In Straparola's tale however, the poor young man is the son of a Bohemian woman, the cat is a fairy in disguise, the princess is named Elisetta, and the castle belongs not to an ogre but to a lord who conveniently perishes in an accident. The poor young man eventually becomes King of Bohemia.[13] An edition of Straparola was published in France in 1560.[10] The abundance of oral versions after Straparola's tale may indicate an oral source to the tale; it also is possible Straparola invented the story.[15]

In 1634, another tale with a trickster cat as hero was published in Giambattista Basile's collection Pentamerone although neither the collection nor the tale were published in France during Perrault's lifetime. In Basile, the lad is a beggar boy called Gagliuso (sometimes Cagliuso) whose fortunes are achieved in a manner similar to Perrault's Puss. However, the tale ends with Cagliuso, in gratitude to the cat, promising the feline a gold coffin upon his death. Three days later, the cat decides to test Gagliuso by pretending to be dead and is mortified to hear Gagliuso tell his wife to take the dead cat by its paws and throw it out the window. The cat leaps up, demanding to know whether this was his promised reward for helping the beggar boy to a better life. The cat then rushes away, leaving his master to fend for himself.[13] In another rendition, the cat performs acts of bravery, then a fairy comes and turns him to his normal state to be with other cats.

It is likely that Perrault was aware of the Straparola tale, since 'Facetious Nights' was translated into French in the sixteenth century and subsequently passed into the oral tradition.[3]

Publication

The oldest record of written history was published in Venice by the Italian author Giovanni Francesco Straparola in his The Facetious Nights of Straparola (c. 1550–53) in XIV-XV. His original title was Costantino Fortunato (lit. Lucky Costantino).

Le Maître Chat, ou le Chat Botté was later published by Barbin in Paris in January 1697 in a collection of tales called Histoires ou contes du temps passé.[3] The collection included "La Belle au bois dormant" ("The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood"), "Le petit chaperon rouge" ("Little Red Riding Hood"), "La Barbe bleue" ("Blue Beard"), "Les Fées" ("The Enchanted Ones", or "Diamonds and Toads"), "Cendrillon, ou la petite pantoufle de verre" ("Cinderella, or The Little Glass Slipper"), "Riquet à la Houppe" ("Riquet with the Tuft"), and "Le Petit Poucet" ("Hop o' My Thumb").[3] The book displayed a frontispiece depicting an old woman telling tales to a group of three children beneath a placard inscribed "CONTES DE MA MERE L'OYE" (Tales of Mother Goose).[4] The book was an instant success.[3]

Le Maître Chat first was translated into English as "The Master Cat, or Puss in Boots" by Robert Samber in 1729 and published in London for J. Pote and R. Montagu with its original companion tales in Histories, or Tales of Past Times, By M. Perrault.[note 1][16] The book was advertised in June 1729 as being "very entertaining and instructive for children".[16] A frontispiece similar to that of the first French edition appeared in the English edition launching the Mother Goose legend in the English-speaking world.[4] Samber's translation has been described as "faithful and straightforward, conveying attractively the concision, liveliness and gently ironic tone of Perrault's prose, which itself emulated the direct approach of oral narrative in its elegant simplicity."[17] Since that publication, the tale has been translated into various languages and published around the world.

Question of authorship

Perrault's son Pierre Darmancour was assumed to have been responsible for the authorship of Histoires with the evidence cited being the book's dedication to Élisabeth Charlotte d'Orléans, the youngest niece of Louis XIV, which was signed "P. Darmancour". Perrault senior, however, was known for some time to have been interested in contes de veille or contes de ma mère l'oye, and in 1693 published a versification of "Les Souhaits Ridicules" and, in 1694, a tale with a Cinderella theme called "Peau d'Ane".[4] Further, a handwritten and illustrated manuscript of five of the tales (including Le Maistre Chat ou le Chat Botté) existed two years before the tale's 1697 Paris publication.[4]

Pierre Darmancour was sixteen or seventeen years old at the time the manuscript was prepared and, as scholars Iona and Peter Opie note, quite unlikely to have been interested in recording fairy tales.[4] Darmancour, who became a soldier, showed no literary inclinations, and, when he died in 1700, his obituary made no mention of any connection with the tales. However, when Perrault senior died in 1703, the newspaper alluded to his being responsible for "La Belle au bois dormant", which the paper had published in 1696.[4]

Analysis

In folkloristics, Puss in Boots is classified as Aarne-Thompson-Uther ATU 545B, "Puss in Boots", a subtype of ATU 545, "The Cat as Helper".[18] Folklorists Joseph Jacobs and Stith Thompson point that the Perrault's tale is the possible source of the Cat Helper story in later European folkloric traditions.[19][20] The tale has also spread to the Americas, and is known in Asia (India, Indonesia and Philippines).[21]

Variations of the feline helper across cultures replace the cat with a jackal or fox.[22][23][24]

Adaptations

Perrault's tale has been adapted to various media over the centuries. Ludwig Tieck published a dramatic satire based on the tale, called Der gestiefelte Kater,[25] and, in 1812, the Brothers Grimm inserted a version of the tale into their Kinder- und Hausmärchen.[26] In ballet, Puss appears in the third act of Tchaikovsky's The Sleeping Beauty in a pas de caractère with The White Cat.[6]

In film and television, Walt Disney produced an animated black and white silent short based on the tale in 1922.[27]

It was also adapted into a manga by the famous Japanese writer and director Hayao Miyazaki, followed by an anime feature film, distributed by Toei in 1969. The title character, Pero, named after Perrault, has since then become the mascot of Toei Animation, with his face appearing in the studio's logo.

In the mid-1980s, Puss in Boots was televised as an episode of Faerie Tale Theatre with Ben Vereen and Gregory Hines in the cast.[28]

Another version from the Cannon Movie Tales series features Christopher Walken as Puss, who in this adaptation is a cat who turns into a human when wearing the boots.

The TV show Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child features the story in a Hawaiian setting. The episode stars the voices of David Hyde Pierce as Puss in Boots, Dean Cain as Kuhio, Pat Morita as King Makahata, and Ming-Na Wen as Lani. In addition, the shapeshifting ogre is replaced with a shapeshifting giant (voiced by Keone Young).

Another adaptation of the character with little relation to the story was in the Pokémon anime episode "Like a Meowth to a Flame," where a Meowth owned by the character Tyson wore boots, a hat, and a neckerchief.

DreamWorks Animation released the animated feature Puss in Boots, with Antonio Banderas reprising his voice-over role of Puss in Boots from the Shrek films, on November 4, 2011. This new film's story bears no similarities to the book. The character later appeared in The Adventures of Puss in Boots voiced by Eric Bauza.

Commentaries

Jacques Barchilon and Henry Pettit note in their introduction to The Authentic Mother Goose: Fairy Tales and Nursery Rhymes that the main motif of "Puss in Boots" is the animal as helper and that the tale "carries atavistic memories of the familiar totem animal as the father protector of the tribe found everywhere by missionaries and anthropologists." They also note that the title is original with Perrault as are the boots; no tale prior to Perrault's features a cat wearing boots.[29]

Folklorists Iona and Peter Opie observe that "the tale is unusual in that the hero little deserves his good fortune, that is if his poverty, his being a third child, and his unquestioning acceptance of the cat's sinful instructions, are not nowadays looked upon as virtues." The cat should be acclaimed the prince of 'con' artists, they declare, as few swindlers have been so successful before or since.[11]

The success of Histoires is attributed to seemingly contradictory and incompatible reasons. While the literary skill employed in the telling of the tales has been recognized universally, it appears the tales were set down in great part as the author heard them told. The evidence for that assessment lies first in the simplicity of the tales, then in the use of words that were, in Perrault's era, considered populaire and du bas peuple, and finally, in the appearance of vestigial passages that now are superfluous to the plot, do not illuminate the narrative, and thus, are passages the Opies believe a literary artist would have rejected in the process of creating a work of art. One such vestigial passage is Puss's boots; his insistence upon the footwear is explained nowhere in the tale, it is not developed, nor is it referred to after its first mention except in an aside.[30]

According to the Opies, Perrault's great achievement was accepting fairy tales at "their own level." He recounted them with neither impatience nor mockery, and without feeling that they needed any aggrandisement such as a frame story—although he must have felt it useful to end with a rhyming moralité. Perrault would be revered today as the father of folklore if he had taken the time to record where he obtained his tales, when, and under what circumstances.[30]

Bruno Bettelheim remarks that "the more simple and straightforward a good character in a fairy tale, the easier it is for a child to identify with it and to reject the bad other." The child identifies with a good hero because the hero's condition makes a positive appeal to him. If the character is a very good person, then the child is likely to want to be good too. Amoral tales, however, show no polarization or juxtaposition of good and bad persons because amoral tales such as "Puss in Boots" build character, not by offering choices between good and bad, but by giving the child hope that even the meekest can survive. Morality is of little concern in these tales, but rather, an assurance is provided that one can survive and succeed in life.[31]

Small children can do little on their own and may give up in disappointment and despair with their attempts. Fairy stories, however, give great dignity to the smallest achievements (such as befriending an animal or being befriended by an animal, as in "Puss in Boots") and that such ordinary events may lead to great things. Fairy stories encourage children to believe and trust that their small, real achievements are important although perhaps not recognized at the moment.[32]

In Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion Jack Zipes notes that Perrault "sought to portray ideal types to reinforce the standards of the civilizing process set by upper-class French society".[8] A composite portrait of Perrault's heroines, for example, reveals the author's idealized female of upper-class society is graceful, beautiful, polite, industrious, well groomed, reserved, patient, and even somewhat stupid because for Perrault, intelligence in womankind would be threatening. Therefore, Perrault's composite heroine passively waits for "the right man" to come along, recognize her virtues, and make her his wife. He acts, she waits. If his seventeenth century heroines demonstrate any characteristics, it is submissiveness.[33]

A composite of Perrault's male heroes, however, indicates the opposite of his heroines: his male characters are not particularly handsome, but they are active, brave, ambitious, and deft, and they use their wit, intelligence, and great civility to work their way up the social ladder and to achieve their goals. In this case of course, it is the cat who displays the characteristics and the man benefits from his trickery and skills. Unlike the tales dealing with submissive heroines waiting for marriage, the male-centered tales suggest social status and achievement are more important than marriage for men. The virtues of Perrault's heroes reflect upon the bourgeoisie of the court of Louis XIV and upon the nature of Perrault, who was a successful civil servant in France during the seventeenth century.[8]

According to fairy and folk tale researcher and commentator Jack Zipes, Puss is "the epitome of the educated bougeois secretary who serves his master with complete devotion and diligence."[33] The cat has enough wit and manners to impress the king, the intelligence to defeat the ogre, and the skill to arrange a royal marriage for his low-born master. Puss's career is capped by his elevation to grand seigneur[8] and the tale is followed by a double moral: "one stresses the importance of possessing industrie et savoir faire while the other extols the virtues of dress, countenance, and youth to win the heart of a princess."[8]

The renowned illustrator of Dickens' novels and stories, George Cruikshank, was shocked that parents would allow their children to read "Puss in Boots" and declared: "As it stood the tale was a succession of successful falsehoods—a clever lesson in lying!—a system of imposture rewarded with the greatest worldly advantages."

Another critic, Maria Tatar, notes that there is little to admire in Puss—he threatens, flatters, deceives, and steals in order to promote his master. She further observes that Puss has been viewed as a "linguistic virtuoso", a creature who has mastered the arts of persuasion and rhetoric to acquire power and wealth.[5]

"Puss in Boots" has successfully supplanted its antecedents by Straparola and Basile and the tale has altered the shapes of many older oral trickster cat tales where they still are found. The morals Perrault attached to the tales are either at odds with the narrative, or beside the point. The first moral tells the reader that hard work and ingenuity are preferable to inherited wealth, but the moral is belied by the poor miller's son who neither works nor uses his wit to gain worldly advantage, but marries into it through trickery performed by the cat. The second moral stresses womankind's vulnerability to external appearances: fine clothes and a pleasant visage are enough to win their hearts. In an aside, Tatar suggests that if the tale has any redeeming meaning, "it has something to do with inspiring respect for those domestic creatures that hunt mice and look out for their masters."[34]

Briggs does assert that cats were a form of fairy in their own right having something akin to a fairy court and their own set of magical powers. Still, it is rare in Europe's fairy tales for a cat to be so closely involved with human affairs. According to Jacob Grimm, Puss shares many of the features that a household fairy or deity would have including a desire for boots which could represent seven-league boots. This may mean that the story of "Puss and Boots" originally represented the tale of a family deity aiding an impoverished family member.[35]

Stefan Zweig, in his 1939 novel, Ungeduld des Herzens, references Puss in Boots' procession through a rich and varied countryside with his master and drives home his metaphor with a mention of Seven League Boots.

References

- Notes

- The distinction of being the first to translate the tales into English was long questioned. An edition styled Histories or Tales of Past Times, told by Mother Goose, with Morals. Written in French by M. Perrault, and Englished by G.M. Gent bore the publication date of 1719, thus casting doubt upon Samber being the first translator. In 1951, however, the date was proven to be a misprint for 1799 and Samber's distinction as the first translator was assured.

- Footnotes

- W. G. Waters, The Mysterious Giovan Francesco Straparola, in Jack Zipes, a c. di, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p 877, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974), The Classic Fairy Tales, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-211559-6. Further info: Little Red Pentecostal Archived 2007-10-23 at the Wayback Machine, Peter J. Leithart, July 9, 2007.

- Opie & Opie 1974, p. 21.

- Opie & Opie 1974, p. 23.

- Tatar 2002, p. 234

- Brown 2007, p. 351

- Opie & Opie 1974, pp. 113–116

- Zipes 1991, p. 26

- Darnton, Robert (1984). The Great Cat Massacre. New York, NY: Basic Books, Ink. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-465-01274-9.

- Opie & Opie 1974, p. 110.

- Opie & Opie 1974, p. 110

- Opie & Opie 1974, p. 18.

- Opie & Opie 1974, p. 112.

- Opie & Opie 1974, p. 20.

- Zipes 2001, p. 877

- Opie & Opie 1974, p. 24.

- Gillespie & Hopkins 2005, p. 351

- Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. pp. 58-59. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 58. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- Jacobs, Joseph. European Folk and Fairy Tales. New York, London: G. P. Putnam's sons. 1916. pp. 239-240.

- Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 59. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- Uther, Hans-Jörg. "The Fox in World Literature: Reflections on a "Fictional Animal"." Asian Folklore Studies 65, no. 2 (2006): 133-60. www.jstor.org/stable/30030396.

- Kaplanoglou, Marianthi. "AT 545B "Puss in Boots" and "The Fox-Matchmaker": From the Central Asian to the European Tradition." Folklore 110 (1999): 57-62. www.jstor.org/stable/1261067.

- Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 58. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- Paulin 2002, p. 65

- Wunderer 2008, p. 202

- "Puss in Boots". The Disney Encyclopedia of Animated Shorts. Archived from the original on 2016-06-05. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- Zipes 1997, p. 102

- Barchilon 1960, pp. 14,16

- Opie & Opie 1974, p. 22.

- Bettelheim 1977, p. 10

- Bettelheim 1977, p. 73

- Zipes 1991, p. 25

- Tatar 2002, p. 235

- Nukiuk H. 2011 Grimm's Fairies: Discover the Fairies of Europe's Fairy Tales, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

- Works cited

- Barchilon, Jacques (1960), The Authentic Mother Goose: Fairy Tales and Nursery Rhymes, Denver, CO: Alan Swallow

- Bettelheim, Bruno (1977) [1975, 1976], The Uses of Enchantment, New York: Random House: Vintage Books, ISBN 0-394-72265-5

- Brown, David (2007), Tchaikovsky, New York: Pegasus Books LLC, ISBN 978-1-933648-30-9

- Gillespie, Stuart; Hopkins, David, eds. (2005), The Oxford History of Literary Translation in English: 1660–1790, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-924622-X

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974), The Classic Fairy Tales, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-211559-6

- Paulin, Roger (2002) [1985], Ludwig Tieck, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-815852-1

- Tatar, Maria (2002), The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- Wunderer, Rolf (2008), "Der gestiefelte Kater" als Unternehmer, Weisbaden: Gabler Verlag, ISBN 978-3-8349-0772-1

- Zipes, Jack David (1991) [1988], Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-90513-3

- Zipes, Jack David (2001), The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p. 877, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- Zipes, Jack David (1997), Happily Ever After, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-91851-0

Further reading

- Neuhaus, Mareike. "The Rhetoric of Harry Robinson's "Cat With the Boots On"." Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal 44, no. 2 (2011): 35-51. www.jstor.org/stable/44029507.

- Nikolajeva, Maria. "Devils, Demons, Familiars, Friends: Toward a Semiotics of Literary Cats." Marvels & Tales 23, no. 2 (2009): 248–67. www.jstor.org/stable/41388926.

- "Jack Ships to the Cat." In: Clever Maids, Fearless Jacks, and a Cat: Fairy Tales from a Living Oral Tradition, edited by Best, Anita; Lovelace, Martin, and Greenhill, Pauline, by Blair Graham, 93-103. University Press of Colorado, 2019. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvqc6hwd.11.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Puss in boots. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Origin of the Story of 'Puss in Boots'

- "Puss in Boots" – English translation from The Blue Fairy Book (1889)

- "Puss in Boots" – Beautifully illustrated in The Colorful Story Book (1941)

Master Cat, or Puss in Boots, The public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Master Cat, or Puss in Boots, The public domain audiobook at LibriVox