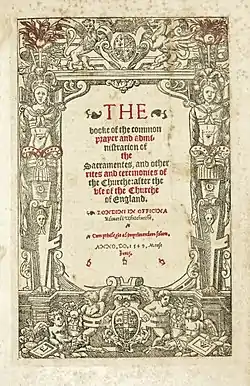

Book of Common Prayer (1549)

The 1549 edition of the Book of Common Prayer is the original version of the Book of Common Prayer (BCP), variations of which are still in use as the official liturgical book of the Church of England and other Anglican churches. Written during the English Reformation, the prayer book was largely the work of Thomas Cranmer, who borrowed from a large number of other sources. Evidence of Cranmer's Protestant theology can be seen throughout the book; however, the services maintain the traditional forms and sacramental language inherited from medieval Catholic liturgies. Criticised by Protestants for being too traditional, it was replaced by a new and significantly revised edition in 1552.

Background

The forms of parish worship in the late medieval church in England followed the Roman Rite. The priest said or sung the liturgy in Latin, but the liturgy itself varied according to local practice. By far the most common form, or "use", found in Southern England was that of Sarum (Salisbury). There was no single book; the services that would be provided by the Book of Common Prayer were to be found in the Missal (the Mass), the Breviary (daily offices), the Manual (the occasional services of baptism, marriage, burial etc.), and the Pontifical (services conducted by a bishop—confirmation, ordination).[1] The chant (plainsong or plainchant) for worship was contained in the Roman Gradual for the Mass, the Antiphonale for the offices, and the Processionale for the litanies.[2]

The liturgical year followed the Roman calendar for the universal feast days, but it also included local feasts as well. The liturgical calendar determined what was to be read at the daily offices and the Mass. By the 1500s, the calendar had become complicated and difficult to use. Furthermore, most of the readings appointed for each day were not drawn from the Bible but were mainly legends about saints' lives. When scripture was assigned, only brief passages were read before moving on to an entirely different chapter. As a result, there was no continuity in scriptural readings throughout the year.[3]

The Book of Common Prayer was a product of the English Reformation. In England, the Reformation began in the 1530s when Henry VIII separated the Church of England from the Roman Catholic Church and the authority of the pope. For the liturgy, Protestant reformers advocated replacing Latin with English, greater lay participation, more Bible reading and sermons, and conforming the liturgy to Protestant theology.[4] Henry VIII, however, was religiously conservative, and Protestants had limited success in reforming the liturgy during his reign.[5]

The work of producing a liturgy in the English language was largely done by Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, starting cautiously in the reign of Henry VIII and then more radically under his son Edward VI. In his early days Cranmer was a conservative humanist and admirer of Erasmus. After 1531, Cranmer's contacts with Protestant reformers from continental Europe helped to change his outlook.[6] By the late 1530s, Cranmer had adopted Lutheran views. By the time the first prayer book was published, Cranmer shared more in common with Reformed theologians like Martin Bucer and Heinrich Bullinger.[7]

Theology

Compared to the liturgies produced by the continental Reformed churches in the same period, the Book of Common Prayer seems relatively conservative. For England, however, it represented a "major theological shift" toward Protestantism.[8] The preface, which contained Cranmer's explanation as to why a new prayer book was necessary, began: "There was never any thing by the wit of man so well devised, or so sure established, which in continuance of time hath not been corrupted."[9]

Cranmer agreed with Reformed Protestant theology,[7] and his doctrinal concerns can be seen in the systematic amendment of source material to remove any idea that human merit contributed to an individual's salvation.[10] The doctrines of justification by faith alone and predestination are central to Cranmer's theology. In justification, God grants the individual faith by which the righteousness of Christ is claimed and the sinner is forgiven. This doctrine is implicit throughout the prayer book, and it had important implications for his understanding of the sacraments. For Cranmer, a sacrament is a "sign of an holy thing" that signifies what it represents but is not identical to it. With this understanding, Cranmer believed that someone who is not one of God's elect receives only the outward form of the sacrament (washing in baptism or eating bread in communion) but does not receive actual grace. Only the elect receive the sacramental sign and the grace. This is because faith—which is a gift only the elect are given—unites the outward sign and the inward grace and makes the sacrament effective. This position was in agreement with the Reformed churches but was opposed to the Roman Catholic and Lutheran views.[11]

Protestants were particularly hostile to the Catholic Church's teaching that each Mass was the sacrifice of Jesus for the redemption of the world. To the reformers, the sacrifice of the Mass was a denial of the "full, perfect and sufficient" sacrifice of Christ. They taught that the Eucharist was a remembrance and representation of this sacrifice, but not the sacrifice itself. Protestants also rejected the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation. According to this doctrine when the priest said the words of institution, the sacramental bread and wine ceased being bread and wine and became the flesh and blood of Christ without changing their appearance. To Protestants, transubstantiation seemed too much like magic, and they rejected it as an explanation for what occurred in the Eucharist.[12]

Protestants opposed the sacrament of penance for two reasons. The first reason was private or auricular confession of sin, which parishioners were supposed to undertake at least once a year. For Protestants, private confession was a problem because it placed a priest between people and God. For Protestants, forgiveness should be sought directly from God. The second reason was that the sacrament of penance demanded some good work as a sign of contrition.[13]

Protestants believed that when a person died he or she would receive either eternal life or eternal damnation depending on whether they had placed their faith in Christ or rejected him. Thus, Protestants denied the Catholic belief in purgatory, a state in which souls are punished for venial or minor sins and those sins that were never confessed. The Catholic Church also taught that the living could take action to reduce the length of time souls spent in purgatory. These included good works such as giving alms, praying to saints and especially the Virgin Mary, and prayer for the dead, especially as part of the Mass.[14] The idea of purgatory was not found in the BCP.[15] Cranmer's theology also led him to remove all instances of prayer to the saints in the liturgy. The literary scholar Alan Jacobs explains this aspect of the prayer book as follows:

In the world of the prayer book, then, the individual Christian stands completely naked before God in a paradoxical setting of public intimacy. There are no powerful rites conducted by sacerdotal figures while people stand some distance away fingering prayer beads or gazing on images of saints whose intercession they crave. Instead, people gather in the church to speak to God, and to be spoken to by Him, in soberly straightforward (though often very beautiful) English. Again and again they are reminded that there is but one Mediator between God and man, Jesus Christ. None other matters; so none other is called upon. The one relevant fact is His verdict upon us, and it is by faith in Him alone that we gain mercy at the time of judgment. All who stand in the church are naked before Him together, exposed in public sight. And so they say, using the first-person singular but using it together, O God, make speed to save me; O Lord, make haste to help me.[16]

Cranmer and his Protestant allies were forced to compromise with Catholic bishops who still held power in the House of Lords. The final form the BCP took was not what either the Protestants nor the Catholics wanted. Historian Albert Pollard wrote that it was "neither Roman nor Zwinglian; still less was it Calvinistic, and for this reason mainly it has been described as Lutheran."[17]

First English services

While Henry was king, the English language was gradually introduced into services alongside Latin. The English-language Great Bible was authorised for use in 1538. Priests were required to read from it during services.[18] The earliest English-language service of the Church of England was the Exhortation and Litany. Published in 1544, it was no mere translation from the Latin. Its Protestant character is made clear by the drastic reduction in the invocation of saints, compressing what had been the major part into three petitions.[19]

Only after the death of Henry VIII and the accession of Edward VI in 1547 could revision proceed faster. On 8 March 1548, a royal proclamation announced the first major reform of the Mass and the Church of England's official eucharistic theology.[20] The "Order of the Communion" was an English liturgy inserted within the Latin Mass after the priest had taken Communion. This was the part of the Mass when the laity would have traditionally been given the sacramental bread to eat.[21]

The Communion order included an exhortation, a penitential section that included confession of sin and absolution as spiritual preparation, and finally the administration of both the sacramental bread and sacramental wine. Communion under both kinds (bread and wine) for the laity was a return to the ancient practice of the church but a departure from the Catholic Church's practice since the 13th century of giving the laity bread only. The order also included what would become known as the Comfortable Words (a selection of encouraging scripture passages read after the absolution) and the Prayer of Humble Access.[22][23]

The Communion Order reflected Protestant theology.[24][25] A significant departure from tradition was that private confession to a priest—long a requirement before receiving the Eucharist—was made optional and replaced with a general confession said by the congregation as a whole. The effect on religious custom was profound as a majority of laypeople, not just Protestants, most likely ceased confessing their sins to their priests.[26] By 1547, Cranmer and other leading Protestants had moved from the Lutheran position to the Reformed position on the Eucharist.[27] Significant to Cranmer's change of mind was the influence of Strasbourg theologian Martin Bucer.[28] This shift can be seen in the communion order's teaching on the Eucharist. Laypeople were instructed that when receiving the sacrament they "spiritually eat the flesh of Christ", an attack on the belief in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist.[29] The Communion order was incorporated into the new prayer book largely unchanged.[30]

Drafting and authorisation

While the English people were becoming accustomed to the new Communion service, Cranmer and his colleagues were working on a complete English-language prayer book.[22] Cranmer is "credited [with] the overall job of editorship and the overarching structure of the book";[31] though, he borrowed and adapted material from other sources.[32] He relied heavily on the Sarum rite[33] and the traditional service books (Missal, Manual, Pontifical and Breviary) as well as from the English primers used by the laity. Other Christian liturgical traditions also influenced Cranmer, including Greek Orthodox and Mozarabic texts. These latter rites had the advantage of being catholic but not Roman Catholic. Cardinal Quiñones' revision of the daily office was also a resource.[7] He borrowed much from German sources, particularly from work commissioned by Hermann von Wied, Archbishop of Cologne; and also from Andreas Osiander (to whom he was related by marriage).[33] The Church Order of Brandenberg and Nuremberg was partly the work of the latter. Many phrases are characteristic of the German reformer Martin Bucer, the Italian Peter Martyr (who was staying with Cranmer at the time he was finalising drafts) or of his chaplain, Thomas Becon.[31]

Early in the draft process, bishops and theologians filled out questionnaires on liturgical theology.[8] In September 1548, bishops and senior clergy met at Chertsey Abbey and then later at Windsor and agreed that "the service of the church ought to be in the mother tongue."[34] These meetings were likely the final steps in a longer process of composition and revision.[8] There is no evidence that the book was ever approved by the Convocations of Canterbury and York. In December 1548, the traditionalist and Protestant bishops debated the prayer book's eucharistic theology in the House of Lords.[35] Despite conservative opposition, Parliament passed the Act of Uniformity on 21 January 1549, and the newly authorised Book of Common Prayer was required to be in use by Whitsunday, 9 June.[22]

Content

The BCP replaced the several regional Latin rites then in use (such as the Use of Sarum, the Use of York and the Use of Hereford) with an English-language liturgy.[36] It was far less complicated than the older system, which required multiple books.[15] The prayer book had provisions for the daily offices, scripture readings for Sundays and holy days, and services for communion, public baptism, confirmation, matrimony, visitation of the sick, burial, purification of women and Ash Wednesday. An ordinal for ordination services was added in 1550.[37][8] There was also a calendar and lectionary, which meant a Bible and a Psalter were the only other books required by a priest.[8]

Liturgical calendar

The prayer book preserved the cycles and seasons of the traditional church year along with a calendar of saints' feasts with collects and scripture readings appropriate for the day.[38] Cranmer opposed praying to saints in hopes they might intercede for the living, but he did believe the saints were role models.[16] For this reason, collects that invoked saints were replaced by new ones that only honored them.[39]

The number of saints days were reduced from 181 to 25. Except for All Saints' Day, they only commemorated New Testament saints and events.[15][40] Other feasts, such as the Assumption and Corpus Christi, were "bulldozed away".[41][42] In addition to the major feasts of Christmas, Easter and Whitsun (or Pentecost),[43] the calendar commemorated the following feasts:[44]

- conversion of St. Paul in January

- Purification of the Virgin Mary and St. Matthias in February

- Annunciation in March

- St. Mark the Evangelist in April

- St. Philip and St. James in May

- St. Barnabas, the Nativity of St. John the Baptist, and St. Peter in June

- St. Mary Magdalene and St. James the Apostle in July

- St. Bartholomew the Apostle in August

- St. Matthew and Michael and All Angels in September

- St. Luke the Evangelist and St. Simon and St. Jude in October

- All Saints' Day and St. Andrew the Apostle in November

- St. Thomas the Apostle, St. Stephen, St. John the Evangelist, and Holy Innocents Day in December

The calendar included what is now called the lectionary, which specified the parts of the Bible to be read at each service. For Cranmer, the main purpose of the liturgy was to familiarise people with the Bible. He wanted a congregation to read through the whole Bible in a year. In the Holy Communion service, four biblical passages were read: an Old Testament passage, a Psalm, a Gospel passage, and a passage from a New Testament book other than the Gospels.[45]

The scripture readings for the daily office followed lectio continua. For Morning and Evening Prayer, the lessons did not change if it was a saints' day. The readings for Holy Communion did change if it was a feast day. This became a problem when a moveable feast fell on the same day as a fixed feast, but the prayer book provided no instructions for determining which feast to celebrate. Directions for solving this issue were not added to the BCP until 1662.[46]

Daily Office

Cranmer's work of simplification and revision was also applied to the daily offices, which were reduced to Morning and Evening Prayer. Cranmer hoped these would also serve as a daily form of prayer to be used by the laity, thus replacing both the late medieval lay observation of the Latin Hours of the Virgin and its English equivalent, the Primer. This simplification was anticipated by the work of Cardinal Quiñones, a Spanish Franciscan, in his abortive revision of the Roman Breviary published in 1537.[47] Cranmer took up Quiñones's principle that everything should be sacrificed to secure continuity in singing the Psalter and reading the Bible. His first draft, produced during Henry's reign, retained the traditional seven distinct canonical hours of Office prayer; but in his second draft, while he retained the Latin, he consolidated these into two.[48]

The 1549 book established a rigorously biblical cycle of readings for Morning and Evening Prayer and a Psalter to be read consecutively throughout each month. A chapter from the Old Testament and the New Testament were read at each service. Both offices had a canticle after each reading. For Morning Prayer, the Te Deum or Benedicite followed the Old Testament reading and the Benedictus followed the New Testament reading. At Evening Prayer, the Magnificat and Nunc dimittis were sung. On Sundays, Wednesdays and Fridays, Cranmer's litany was to follow Morning Prayer.[49]

Clergy were required to say both Morning and Evening Prayer daily. If this requirement was followed, a clergyman would have read the entire Old Testament once a year. He would have read the New Testament three times a year.[50]

Holy Communion

When it came to the Eucharist, a priority for Protestants was to replace the Roman Catholic teaching that the Mass was a sacrifice to God ("the very same sacrifice as that of the cross") with the Protestant teaching that it was a service of thanksgiving and spiritual communion with Christ.[7][51] As a compromise with conservatives, the word Mass was kept, with the service titled "The Supper of the Lord and the Holy Communion, commonly called the Mass."[52] It also preserved much of the medieval structure of the Mass—stone altars remained, the clergy wore traditional vestments, much of the service was sung, and the priest was instructed to put the Communion wafer into a communicant's mouth instead of in their hand.[49][15] Nevertheless, the first BCP was a "radical" departure from traditional worship in that it "eliminated almost everything that had till then been central to lay Eucharistic piety".[43] Cranmer's intention was to suppress notions of sacrifice and transubstantiation in the Mass.[52]

In the new liturgy, the priest faced the congregation instead of turning his back to them.[53] The offertory departed from the medieval pattern, which had focused on offering the bread and wine which were to be consecrated as the body and blood of Christ. The new offertory was simply a collection for the poor and referred only to an offering of praise and thanksgiving for Christ's one sacrifice.[54] The prayer of consecration was based on the Sarum version of the Canon of the Mass. Before the words of institution, the priest asks God the Father "with thy holy spirit and word, vouchsafe to bless and sanctify these thy gifts and creatures of bread and wine, that they may be unto us the body and blood of thy most dearly beloved son Jesus Christ".[54] This epiclesis or invocation of the Holy Spirit was not meant to imply that a transformation occurred in the elements. Cranmer made clear elsewhere that to bless something meant only to set it apart for a holy purpose. In praying "that they may be unto us the body and blood", Cranmer meant that the bread and wine would represent the body and blood, which can only be received spiritually.[54]

Three sacrifices were mentioned; the first was Christ's sacrifice on the cross. The second was the congregation's sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving, and the third was the offering of "ourselves, our souls and bodies, to be a reasonable, holy and lively sacrifice" to God.[51] While the medieval Canon "explicitly identified the priest's action at the altar with the sacrifice of Christ", the prayer book broke this connection by stating the church's offering of thanksgiving in the Eucharist was not the same as Christ's sacrifice.[38] Christ's sacrifice on the cross was "his one oblation of himself once offered ... a full, perfect and sufficient sacrifice, oblation and satisfaction, for the sins of the whole world".[54] Instead of the priest offering the sacrifice of Christ to the Father, the assembled offered their praises and thanksgivings. The Eucharist was now to be understood as merely a means of partaking in and receiving the benefits of Christ's sacrifice.[55][56] To further stress this, there was no elevation of the consecrated bread and wine, and eucharistic adoration was prohibited. The elevation had been the central moment of the medieval Mass, attached as it was to the idea of real presence.[36][57]

For centuries it was held that Cranmer's theology of Christ's presence in the Eucharist was Zwinglian. It was actually closer to the Calvinist spiritual presence view and can be described as Receptionism and Virtualism: i.e. Christ is really present but by the power of the Holy Spirit.[58][59] The words of administration in the 1549 rite were deliberately ambiguous: "The body of our Lord Jesus Christ which was given for thee, preserve thy body and soul unto everlasting life". This could be understood as identifying the bread with the body of Christ or (following Cranmer's theology) as a prayer that the communicant might spiritually receive the body of Christ by faith.[54]

In late medieval England, lay people regularly received communion only once a year at Easter. The primary focus of congregational worship was taken to be attendance at the consecration and adoration of the elevated consecrated host. For most of the Mass, congregants were allowed to pray privately, often with their rosaries. Cranmer hoped to change this by establishing the practice of weekly congregational Communion with instructions that Communion should never be received by the priest alone. In the 1549 rite, those not receiving Communion were supposed to leave after the offertory. If there were no communicants, the service was to end without Communion—known as Ante-Communion—and this was how it frequently did end. Ante-Communion included all the parts of the Communion service that came before the actual sacrament (prayers, the reading of the Decalogue, the recitation of the Nicene Creed, a sermon, and prayers for the church). Weekly Holy Communion would not become common within the Church of England until the Victorian Era.[54][60]

Baptism

In the Middle Ages, the church taught that children were born with original sin and that only baptism could remove it.[61] Baptism was, therefore, essential to salvation.[62] It was feared that children who died without baptism faced eternal damnation or limbo.[63] A priest would perform an infant baptism soon after birth on any day of the week, but in cases of emergency, a midwife could baptise a child at birth. The traditional baptism service was long and repetitive. It was also spoken in Latin. The priest only spoke English when exhorting the godparents.[62]

Cranmer did not believe that baptism was absolutely necessary for salvation. He did believe that it was ordinarily necessary and to refuse baptism would be a rejection of God's grace. In agreement with Reformed theology, however, Cranmer believed that salvation was determined by God's unconditional election, which was predestined. If an infant was one of the elect, dying unbaptised would not affect the child's salvation.[62] To Cranmer, baptism and the Eucharist were the only dominical sacraments (sacraments instituted by Christ himself) and of equal importance. The prayer book made public baptism the norm, so a congregation could observe and be reminded of their own baptism. In cases of emergency, a private baptism could be performed at home.[62]

Largely based on Martin Luther's baptism service, which simplified the medieval rite,[62] the prayer book's service maintained a traditional form and sacramental character.[38] The service begins with these words:

Dear beloved, forasmuch as all men be conceived and born in sin, and that no man born in sin, can enter into the kingdom of God (except he be regenerate, and born anew of water, and the holy ghost) I beseech you to call upon God the father through our Lord Jesus Christ, that of his bounteous mercy he will grant to these children that thing, which by nature they cannot have, that is to say, they may be baptized with the holy ghost, and received into Christ’s holy Church, and be made lively members of the same.[64]

The new service preserved some of the symbolic actions and repetitive prayers found in the medieval rite.[62] The old rite included many prayers of minor exorcism.[62] The new service only had one, with the priest praying, "I command thee, unclean spirit, in the name of the father, of the son, and of the holy ghost, that thou come out, and depart from these infants."[65] The rite also included a blessing of the water in the baptismal font. Baptismal vows were made by the godparents on behalf of the child. The child was signed with the cross prior to baptism and afterward dressed in traditional white baptismal clothing and anointed with chrism oil.[38]

Confirmation and catechism

The Book of Common Prayer also included a service for confirmation and a catechism. In Catholicism, confirmation was a sacrament believed to give grace for the Christian life after baptism and was always performed by a bishop.[66]

Cranmer saw confirmation as an opportunity for children who had been baptised as infants to personally affirm their faith.[66] At confirmation, children would accept for themselves the baptismal vows made by godparents on their behalf. Before being confirmed, a child would learn the catechism, which was supposed to be taught in church on Sundays. The catechism included the Apostles' Creed, the Ten Commandments, the Lord's Prayer, and a discussion of the individual's duty to God and neighbor. Everyone was required to know these in order to receive Communion.[67]

The confirmation service followed the Sarum rite.[38] The bishop prayed that the confirmand would be strengthened with the "inward unction of thy Holy Ghost". Afterwards, the bishop made the sign of the cross on the child's forehead and laid his hands on the head. The only significant change to the traditional rite was that the confirmand was not anointed with chrism oil.[67]

Marriage

The marriage service was largely a translation of the Sarum rite.[68] The first part of the service took place in the nave of the church and included an opening pastoral discourse, a time to declare objections or impediments to the marriage, and the marriage vows. The couple then moved to the chancel for prayers and to receive Holy Communion.[67]

The prayer book rejected the idea that marriage was a sacrament[67] while also repudiating the common medieval belief that celibacy was holier than married life. The prayer book called marriage a "holy estate" that "Christ adorned and beautified with his presence, and first miracle that he wrought in Cana of Galilee."[69] Sacerdotal elements in the rite were removed, and the emphasis was on the groom and bride as the true ministers of the wedding. The wedding ring was retained, but it was not blessed. Cranmer believed that blessings applied to people not things, so the couple was blessed.[67]

The Sarum rite stated there were two purposes for marriage: procreation of children and avoidance of fornication. Cranmer added a third purpose: "for the mutual society, help, and comfort, that the one ought to have of the other, both in prosperity and adversity."[68] In the Sarum rite, the husband vowed "to have and to hold from this day forward, for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness, and in health, till death us depart." Cranmer added the words "to love and to cherish" (for the wife "to love, cherish, and obey").[68]

Visitation of the sick

The office for the visitation of the sick was a shortened version of the Sarum rite. It featured prayers for healing, a long exhortation by the priest and a reminder that the sick person needed to examine their conscience and repent of sin while there was still time. The rite had a penitential tone, which was reinforced by the option to make private confession to the priest who would then grant absolution. This was the only form for absolving individuals provided in the prayer book and was to be used for all other private confessions. The visitation rite also included anointing of the sick, but a distinction was made between the visible oil and the inward anointing of the Holy Spirit.[67][16]

Communion of the sick was also provided for in the prayer book. While the Catholic practice of reserving the sacrament was forbidden, the priest could celebrate a shortened Communion service at the sick person's house or the sacrament could be brought directly from a Communion service at the parish church to be administered to the sick.[67]

In the medieval rite, there were prayers to saints asking for their intercession on behalf of the sick. These prayers were not included in the prayer book liturgy.[70] Other changes made included the removal of symbolic gestures and sacramentals. For example, the prayer book rite made anointing of the sick optional with only one anointing on the forehead or chest. In the old rite, the eyes, ears, lips, limbs and heart were anointed to symbolise, in the words of historian Eamon Duffy, "absolution and surrender of all the sick person's senses and faculties as death approached".[71]

Burial

The Order for the Burial of the Dead was focused on the resurrection of Jesus as a pledge and guarantee of the resurrection and glorification of all believers.[72] It included a procession through the church yard, the burial, a service in church and Holy Communion.[73] There were remnants of prayer for the dead and the Requiem Mass, such as the provision for celebrating Communion at a funeral.[42] At the same time, much of the traditional funeral rites were removed. For example, the service in the house and all other processions were eliminated.[73]

Ordinal and vestments

When first published, the prayer book lacked an ordinal, the book containing the rites for the ordination of deacons and priests and the consecration of bishops. This was added to the BCP in 1550. The ordinal adopted the Protestant doctrine of sola scriptura and has ordination candidates affirm they are "persuaded that the holy scriptures contain sufficiently all doctrine required of necessity for eternal salvation through faith in Jesus Christ".[50]

The services were also simplified. For Cranmer and other reformers, the essential part of ordination was the laying on hands with prayer. In the traditional service, the ordination candidate would be anointed, put on Mass vestments and receive the eucharistic vessels to symbolise his new role. In the prayer book, however, the only thing the candidate was given was a Bible from which he would teach.[74]

Priests still wore vestments—the prayer book recommended the cope rather than the chasuble.[38] When being consecrated, bishops were to wear a black chimere over a white rochet. This requirement offended John Hooper, who initially refused to wear the offensive garments to become bishop of Gloucester. His refusal launched the first vestments controversy in the Church of England.[75]

Music

The Latin Mass and daily office traditionally used monophonic chant for music. While Lutheran churches in Germany continued to use chant in their services, other Protestant churches in Europe were replacing chant with exclusive psalmody. The English reformers followed the Lutheran example by retaining chant for their new vernacular services. There was, however, a demand to make chant less elaborate so that the liturgical text could be heard clearly. This had been a common concern for humanists such as Erasmus.[2] Cranmer preferred simple plainsong that was "functional, comprehensible to and even performable by any persevering member of a congregation".[76]

The English litany was published along with simple plainsong based on the chant used in the Sarum rite.[2] When the BCP was published, there was initially no music because it would take time to replace the church's body of Latin music.[42] Theologian Gordon Jeanes writes that "Musically the greatest loss was of hymnody, reflecting Cranmer’s own acknowledged lack of compositional skill."[7]

John Merbecke's Book of Common Prayer noted, published in 1550, also used simple plainsong musical settings.[77] Merbecke's work was intended to be sung by the "singing men" of cathedrals and collegiate churches, not by the congregation. In smaller parish churches, every part of the liturgy would have been spoken. Merbecke's musical settings experienced a revival in popularity during the 19th century, when his settings were revised to be sung by congregations.[78] Some of those settings have remained in use into the 20th century.[77]

Reception

The 1549 Book of Common Prayer was a temporary compromise between reformers and conservatives.[79] It provided Protestants with a service free from what they considered superstition, while maintaining the traditional structure of the Mass.[80]

It was criticised by Protestants for being too susceptible to Roman Catholic re-interpretation. Conservative clergy took advantage of loopholes in the 1549 prayer book to make the new liturgy as much like the old Latin Mass as possible, including elevating the Eucharist.[81] The conservative Bishop Gardiner endorsed the prayer book while in prison,[80] and historian Eamon Duffy notes that many lay people treated the prayer book "as an English missal".[82] Nevertheless, it was unpopular in the parishes of Devon and Cornwall where, along with severe social problems, its introduction was one of the causes of the Prayer Book Rebellion in the summer of that year, partly because many Cornish people lacked sufficient English to understand it.[83][84]

Protestants considered the book too traditional. Martin Bucer identified 60 problems with the prayer book, and the Italian Peter Martyr Vermigli provided his own complaints. Shifts in Eucharistic theology between 1548 and 1552 also made the prayer book unsatisfactory—during that time English Protestants achieved a consensus rejecting any real bodily presence of Christ in the Eucharist. Some influential Protestants such as Vermigli defended Zwingli's symbolic view of the Eucharist. Less radical Protestants such as Bucer and Cranmer advocated for a spiritual presence in the sacrament.[85] Cranmer himself had already adopted receptionist views on the Lord's Supper.[86] In April 1552, a new Act of Uniformity authorised a revised Book of Common Prayer to be used in worship by 1 November.[87]

Centuries later, the 1549 prayer book would become popular among Anglo-Catholics. Nevertheless, Cranmer biographer Diarmaid MacCulloch comments that this would have "surprised and probably distressed Cranmer".[52]

See also

References

Citations

- Harrison & Sansom 1982, p. 29.

- Leaver 2006, p. 39.

- Strout 2018, pp. 309–312.

- Moorman 1983, pp. 20–21.

- Jacobs 2013, p. 10.

- MacCulloch 1996, p. 60.

- Jeanes 2006, p. 28.

- Jeanes 2006, p. 26.

- Procter & Frere 1965, p. 45.

- MacCulloch 1996, p. 418.

- Jeanes 2006, p. 30.

- Moorman 1983, pp. 24–25.

- Moorman 1983, pp. 23–24.

- Moorman 1983, p. 22.

- Moorman 1983, p. 26.

- Jacobs 2013, p. 38.

- Pollard (1905, p. 220) quoted in Strout (2018, p. 315).

- Jacobs 2013, p. 13.

- Procter & Frere 1965, p. 31.

- MacCulloch 1996, p. 384.

- Jacobs 2013, p. 17.

- Jeanes 2006, p. 23.

- Moorman 1983, p. 25.

- Haigh 1993, p. 173.

- Duffy 2005, p. 459.

- Marshall 2017, p. 315.

- Marshall 2017, pp. 322–323.

- MacCulloch 1996, p. 380.

- MacCulloch 1996, p. 386.

- MacCulloch 1996, p. 385.

- MacCulloch 1996, p. 417.

- Jeanes 2006, p. 27.

- MacCulloch 1996, p. 414.

- Procter & Frere 1965, p. 47.

- MacCulloch 1996, pp. 404–407.

- Marshall 2017, p. 324.

- Gibson 1910.

- Marshall 2017, pp. 324–325.

- Strout 2018, pp. 314–315.

- Strout 2018, p. 315.

- Duffy 2005, p. 465.

- Marshall 2017, p. 325.

- Duffy 2005, pp. 464–466.

- Strout 2018, p. 319.

- Jacobs 2013, pp. 26–27.

- Strout 2018, pp. 319–320.

- Procter & Frere 1965, p. 27.

- Procter & Frere 1965, p. 34.

- Jeanes 2006, p. 31.

- Moorman 1983, p. 18.

- Moorman 1983, p. 27.

- MacCulloch 1996, p. 412.

- Winship 2018, p. 12.

- Jeanes 2006, p. 32.

- Jones et al. 1992, pp. 101–105.

- Thompson 1961, pp. 234–236.

- MacCulloch 1996, p. 413.

- Jones et al. 1992, p. 36.

- MacCulloch 1996, p. 392.

- Jacobs 2013, pp. 18, 30–31.

- Jacobs 2013, p. 34.

- Jeanes 2006, p. 34.

- Jacobs 2013, p. 34 and footnote 17.

- Jacobs 2013, pp. 34–35.

- Jacobs 2013, p. 35.

- Jeanes 2006, p. 35.

- Jeanes 2006, p. 36.

- Jacobs 2013, p. 40.

- Jacobs 2013, p. 39.

- Jacobs 2013, p. 36.

- Duffy 2005, p. 466.

- Jacobs 2013, p. 42.

- Jeanes 2006, p. 38.

- Moorman 1983, p. 28.

- Marshall 2017, pp. 340–341.

- MacCulloch 1996, p. 331.

- MacCulloch 1996, pp. 330–331.

- Leaver 2006, p. 40.

- MacCulloch 1996, p. 410.

- Haigh 1993, p. 174.

- Marshall 2017, p. 339.

- Duffy 2005, p. 470.

- Duffy 2003, pp. 131ff.

- Caraman 1994.

- Haigh 1993, p. 179.

- MacCulloch (1996, pp. 461, 492) quotes Cranmer as explaining "And therefore in the book of the holy communion, we do not pray that the creatures of bread and wine may be the body and blood of Christ; but that they may be to us the body and blood of Christ" and also "I do as plainly speak as I can, that Christ's body and blood be given to us in deed, yet not corporally and carnally, but spiritually and effectually."

- Duffy 2005, p. 472.

Bibliography

- Caraman, Philip (1994), The Western Rising 1549: the Prayer Book Rebellion, Tiverton: Westcountry Books, ISBN 1-898386-03-X

- Duffy, Eamon (2003), The Voices of Morebath: Reformation and Rebellion in an English Village, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-09825-1

- Duffy, Eamon (2005). The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, c. 1400–c. 1580 (2nd ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10828-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gibson, E.C.S (1910). The First and Second Prayer Books of Edward VI. Everyman's Library.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Haigh, Christopher (1993). English Reformations: Religion, Politics, and Society Under the Tudors. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822162-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harrison, D.E.W.; Sansom, Michael C (1982), Worship in the Church of England, London: SPCK, ISBN 0-281-03843-0

- Jacobs, Alan (2013). The Book of Common Prayer: A Biography. Lives of Great Religious Books. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691191782.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jeanes, Gordon (2006). "Cranmer and Common Prayer". In Hefling, Charles; Shattuck, Cynthia (eds.). The Oxford Guide to The Book of Common Prayer: A Worldwide Survey. Oxford University Press. pp. 21–38. ISBN 978-0-19-529756-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Cheslyn; Wainwright, Geoffrey; Yarnold, Edward; Bradshaw, Paul, eds. (1992). The Study of Liturgy (revised ed.). SPCK. ISBN 978-0-19-520922-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leaver, Robin A. (2006). "The Prayer Book 'Noted'". In Hefling, Charles; Shattuck, Cynthia (eds.). The Oxford Guide to The Book of Common Prayer: A Worldwide Survey. Oxford University Press. pp. 39–43. ISBN 978-0-19-529756-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid (1996). Thomas Cranmer: A Life (revised ed.). London: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300226577.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marshall, Peter (2017). Heretics and Believers: A History of the English Reformation. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300170629.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moorman, John R. H. (1983). The Anglican Spiritual Tradition. Springfield, Illinois, US: Templegate Publishers. ISBN 0-87243-139-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pollard, Albert Frederick (1905). Thomas Cranmer and the English Reformation, 1489-1556. G. P. Putnam's Sons.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Procter, F; Frere, W H (1965), A New History of the Book of Common Prayer, St. Martin's Press

- Strout, Shawn (September 2018). "Thomas Cranmer's Reform of the Sanctorale Calendar". Anglican and Episcopal History. Historical Society of the Episcopal Church. 87 (3): 307–324. JSTOR 26532536.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, Bard (1961). Liturgies of the Western church. Meridian Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Winship, Michael P. (2018). Hot Protestants: A History of Puritanism in England and America. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12628-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- "The Book of Common Prayer - 1549". justus.anglican.org. Society of Archbishop Justus.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)