Brain as food

The brain, like most other internal organs, or offal, can serve as nourishment. Brains used for nourishment include those of pigs, squirrels, rabbits, horses, cattle, monkeys, chickens, fish, lamb and goats. In many cultures, different types of brain are considered a delicacy.

Cultural consumption

The brain of animals features in French cuisine, in dishes such as cervelle de veau and tête de veau. A dish called maghaz is a popular cuisine in Pakistan, Bangladesh, parts of India, and diaspora countries. In Turkish cuisine brain can be fried, baked, or consumed as a salad. In Chinese cuisine, brain is a delicacy in Chongqing or Sichuan cuisine, and it is often cooked in spicy hot pot or barbecued. In the southern part of China, pig brain is used for "Tianma Zhunao Tang". In South India goat brain curry or fry is a delicacy.

Similar delicacies from around the world include Mexican tacos de sesos.[1] The Anyang tribe of Cameroon practiced a tradition in which a new tribal chief would consume the brain of a hunted gorilla, while another senior member of the tribe would eat the heart.[2] Indonesian cuisine specialty in Minangkabau cuisine also served beef brain in a coconut-milk gravy named gulai banak (beef brain curry).[3][4] In Cuban cuisine, "brain fritters" are made by coating pieces of brain with bread crumbs and then frying them.[5]

Nutritional composition

DHA, an important omega-3 fatty acid, is found concentrated in mammalian brains. For example, according to Nutrition Data, 85g (3oz) of cooked beef brain contains 727mg of DHA.[6] By way of comparison, the NIH has determined that small children need at least 150mg of DHA per day, and pregnant and lactating women need at least 300mg of DHA.[7]

The makeup of the brain is about 12% lipids, most of which are located in myelin (which itself is 70–80% fat).[8] Specific fatty acid ratios will depend in part on the diet of the animal it is harvested from. The brain is also very high in cholesterol. For example, a single 140g (5oz) serving of "pork brains in milk gravy" can contain 3500mg of cholesterol (1170% of the USRDA).[9]

Prions

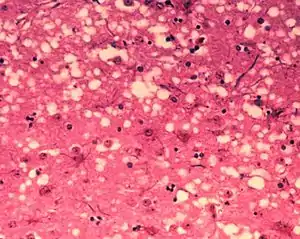

Prions are misfolded proteins with the ability to transmit their misfolded shape onto normal variants of the same protein. They characterize several fatal and transmissible neurodegenerative diseases in humans and many other animals.[10] It is not known what causes the normal protein to misfold, but the abnormal three-dimensional structure is suspected of conferring infectious properties, collapsing nearby protein molecules into the same shape. The word prion derives from "proteinaceous infectious particle".[11][12][13] The hypothesized role of a protein as an infectious agent stands in contrast to all other known infectious agents such as viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites, all of which contain nucleic acids (DNA, RNA or both).

Prions form abnormal aggregates of proteins called amyloids, which accumulate in infected tissue and are associated with tissue damage and cell death.[14] Amyloids are also responsible for several other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease.[15][16] Prion aggregates are stable, and this structural stability means that prions are resistant to denaturation by chemical and physical agents: they cannot be destroyed by ordinary disinfection or cooking. This makes disposal and containment of these particles difficult.Beef brain consumption has been linked to Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease outbreaks in humans, so many countries have strict regulations about what parts of cattle can be sold for human consumption. [17] Another prion disease called kuru has been traced to a funerary ritual among the Fore people of Papua New Guinea in which those close to the dead would eat the brain of the deceased to create a sense of immortality.[18]

References

- "Weird Foods: Mammal". Weird-Food.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2005. Retrieved 14 October 2005.

- Meder, Angela. "Gorillas in African Culture and Medicine". Gorilla Journal. Archived from the original on 5 September 2005. Retrieved 14 October 2005.

- "Beef Brain Curry (Gulai Otak)". Melroseflowers.com. Retrieved 2013-12-07.

- "Brain Fritters". Cubanfoodmarket.com. Archived from the original on 2014-11-15. Retrieved 2013-12-07.

- "Beef, variety meats and by-products, brain, cooked, simmered". Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- "DHA/EPA and the Omega-3 Nutrition Gap / Recommended Intakes".

- "Brain Facts and Figures". Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- "Pork Brains in Milk Gravy". Archived from the original on 2012-09-30. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- "Prion diseases". Diseases and conditions. National Institute of Health.

- "Prion diseases". United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019-05-03.

- "What Is a Prion?". Scientific American. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Prion infectious agent". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Dobson CM (February 2001). "The structural basis of protein folding and its links with human disease". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 356 (1406): 133–45. doi:10.1098/rstb.2000.0758. PMC 1088418. PMID 11260793.

- Golde, Todd E.; Borchelt, David R.; Giasson, Benoit I.; Lewis, Jada (2013-05-01). "Thinking laterally about neurodegenerative proteinopathies". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 123 (5): 1847–1855. doi:10.1172/JCI66029. ISSN 0021-9738. PMC 3635732. PMID 23635781.

- Irvine GB, El-Agnaf OM, Shankar GM, Walsh DM (2008). "Protein aggregation in the brain: the molecular basis for Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases". Molecular Medicine. 14 (7–8): 451–64. doi:10.2119/2007-00100.Irvine. PMC 2274891. PMID 18368143.

- Collinge, John (2001). "Prion diseases of humans and animals: their causes and molecular basis". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 24: 519–50. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.519. PMID 11283320.

- Collins, S; McLean CA; Masters CL (2001). "Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker syndrome, fatal familial insomnia, and kuru: a review of these less common human transmissible spongiform encephalopathies". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 8 (5): 387–97. doi:10.1054/jocn.2001.0919. PMID 11535002.

External links

Media related to Brain (as food) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Brain (as food) at Wikimedia Commons