Bristol Cathedral

Bristol Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, is the Church of England cathedral in the city of Bristol, England. Founded in 1140 and consecrated in 1148,[2] it was originally St Augustine's Abbey but after the Dissolution of the Monasteries it became in 1542 the seat of the newly created Bishop of Bristol and the cathedral of the new Diocese of Bristol. It is a Grade I listed building.[1]

| Bristol Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity | |

The west front of Bristol Cathedral | |

Bristol Cathedral shown within Bristol | |

| 51°27′06″N 2°36′03″W | |

| Location | Bristol |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Churchmanship | Central/High church |

| Website | bristol-cathedral.co.uk |

| History | |

| Consecrated | 11 April 1148 |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Grade I listed building |

| Designated | 8 January 1959 |

| Style | Norman, Gothic, Gothic Revival |

| Years built | 1220–1877 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 300 feet (91 m)[1] |

| Nave length | 125 feet (38 m)[1] |

| Width across transepts | 29 feet (8.8 m)[1] |

| Nave height | 52 feet (16 m)[1] |

| Choir height | 50 feet (15 m)[1] |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Worcester (until 1541) Gloucester (1541–43) Bristol (1543–1836) Gloucester and Bristol (1836–1897) Bristol (1897–present) |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Viv Faull |

| Dean | Mandy Ford |

| Precentor | Nicola Stanley |

| Chancellor | Michael Roden |

| Canon(s) | Martin Gainsborough (Bishop's Chaplain) 1 vacant (Diocesan Canon) |

| Laity | |

| Organist(s) | Mark Lee, Paul Walton (Assistant Organist) |

The eastern end of the church includes fabric from the 12th century, with the Elder Lady Chapel which was added in the early 13th century. Much of the church was rebuilt in the English Decorated Gothic style during the 14th century despite financial problems within the abbey. In the 15th century the transept and central tower were added. The nave was incomplete at the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1539 and was demolished. In the 19th century Gothic Revival a new nave was built by George Edmund Street partially using the original plans. The western twin towers, designed by John Loughborough Pearson, were completed in 1888.

Located on College Green, the cathedral has tall Gothic windows and pinnacled skyline. The eastern end is a hall church in which the aisles are the same height as the Choir and share the Lierne vaults. The late Norman chapter house, situated south of the transept, contains some of the first uses of pointed arches in England. In addition to the cathedral's architectural features, it contains several memorials and an historic organ. Little of the original stained glass remains with some being replaced in the Victorian era and further losses during the Bristol Blitz.

History

Foundation and 12th century

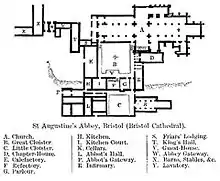

Bristol Cathedral was founded as St Augustine's Abbey in 1140 by Robert Fitzharding, a wealthy local landowner and royal official who later became Lord Berkeley.[3][4] As the name suggests, the monastic precinct housed Augustinian canons.[5] The original abbey church, of which only fragments remain, was constructed between 1140 and 1148 in the Romanesque style, known in England as Norman.[6][7] The Venerable Bede made reference to St Augustine of Canterbury visiting the site in 603ACE, and John Leland had recorded that it was a long-established religious shrine.[8] William Worcester recorded in his Survey of Bristol that the original Augustinian abbey church was further to the east of the current site, though that was rebuilt as the church of St Augustine the Less. That site was bombed during World War II and the site built on by the Royal Hotel, but archaeological finds were deposited with Bristol Museum and Art Gallery.[8] The dedication ceremony was held on 11 April 1148, and was conducted by the Bishops of Worcester, Exeter, Llandaff, and St Asaph.[9]

Further stone buildings were erected on the site between 1148 and 1164.[10] Three examples of this phase survive, the chapterhouse and the abbey gatehouse, now the diocesan office, together with a second Romanesque gateway, which originally led into the abbot's quarters.[11] T.H.B. Burrough, a local architectural historian, describes the former as "the finest Norman chapter house still standing today".[12] In 1154 King Henry II greatly increased the endowment and wealth of the abbey as reward to Robert Fitzharding, for his support during The Anarchy which brought Henry II to the throne.[8] By 1170 enough of the new church building was complete for it to be dedicated by four bishops – Worcester, Exeter, Llandaff and St Asaph.[8]

13th century

Under Abbot David (1216–1234) there was a new phase of building, notably the construction in around 1220 of a chapel dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary, abutting the northern side of the choir.[13] This building, which still stands, was to become known as the "Elder Lady Chapel".[14] The architect, referred to in a letter as 'L', is thought to have been Adam Lock, master mason of Wells Cathedral.[15] The stonework of the eastern window of this chapel is by William the Geometer, of about 1280.[16] Abbot David argued with the convent and was deposed in 1234 to be replaced by William of Bradstone who purchased land from the mayor to build a quay and the Church of St Augustine the Less. The next abbot was William Longe, the Chamberlain of Keynsham, whose reign was found to have lacked discipline and had poor financial management. In 1280 he resigned and was replaced as abbot by Abbot Hugh who restored good order, with money being given by Edward I.[9]

14th–16th century

Under Abbot Edward Knowle (1306–1332), a major rebuilding of the Abbey church began despite financial problems.[9] Between 1298 and 1332 the eastern part of the abbey church was rebuilt in the English Decorated Gothic style.[17] He also rebuilt the cloisters, the canons' dining room, the King's Hall and the King's Chamber.[8] The Black Death is likely to have affected the monastery and when William Coke became abbot in 1353 he obtained a papal bull from Pope Urban V to allow him to ordain priests at a younger age to replace those who had died. Soon after the election of his successor, Henry Shellingford, in 1365 Edward III took control of the monastery and made The 4th Baron Berkeley its commissioner to resolve the financial problems. In the late 14th and early 15th centuries Abbots Cernay and Daubeney restored the fortunes of the order, partly by obtaining the perpetual vicarage of several local parishes. These difficulties meant that little building work had been undertaken for nearly 100 years. However, in the mid-15th century, the number of Canons increased and the transept and central tower were constructed.[9] Abbot John Newland, (1481–1515), also known as 'Nailheart' due to his rebus of a heart pierced by three nails,[8] began the rebuilding of the nave, but it was incomplete at the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1539. Newland also rebuilt the cloisters, the upper part of the Gatehouse, the canons' dormitory and dining room, and the Prior's Lodging (parts of which remained until 1884 as they were built into Minster House).[8]

The partly built nave was demolished and the remaining eastern part of the church closed until it reopened as a cathedral under the secular clergy. In an edict dated June 1542, Henry VIII and Thomas Cranmer raised the building to rank of Cathedral of a new Diocese of Bristol.[18] The new diocese was created from parts of the Diocese of Gloucester and the Diocese of Bath and Wells;[18] Bristol had been, before the Reformation, and the erection of Gloucester diocese, part of the Diocese of Worcester. Paul Bush, (died 1558) a former royal household chaplain, was created the first Bishop of Bristol.[19] The new cathedral was dedicated to the Holy and Undivided Trinity.[1][20]

19th century

In the 1831 Bristol Riots, a mob broke into the Chapter House, destroying a lot of the early records of the Abbey and damaging the building.[8] The church itself was protected from the rioters by William Phillips, sub-sacrist, who barred their entry to the church at the cloister door.[21]

Between the merger of the old Bristol diocese back into the Gloucester diocese on 5 October 1836[22] and the re-erection of the new independent Bristol diocese on 9 July 1897,[23] Bristol Cathedral was a joint and equal cathedral of the Diocese of Gloucester and Bristol.

Giles Gilbert Scott was consulted in 1860 and suggested removing the screen dated 1542 to provide 'a nave of the grandest possible capacity'. The work at this time also removed some of the more vulgar medieval misericords in the choir stalls.[3] With the 19th century's Gothic Revival signalling renewed interest in Britain's ancient architectural heritage, a new nave, in a similar style to the eastern end, based on original 15th-century designs, was added between 1868 and 1877 by George Edmund Street,[13][24] clearing the houses which had been built, crowded onto the site of the former nave, including Minster House.[3] In 1829 leases for these houses were refused by the Dean and Chapter because the houses had become 'very notoriously a receptacle for prostitutes'.[3] The rebuilding of the nave was paid for by public subscription including benefactors such as Greville Smyth of Ashton Court, The Miles family of Kings Weston House, the Society of Merchant Venturers, Stuckey's Bank, William Gibbs of Tyntesfield, and many other Bristol citizens.[3] The opening ceremony was on 23 October 1877.[25] However, the west front with its twin towers, designed by John Loughborough Pearson,[26] was only completed in 1888.[27] The niches around the north porch originally held statues of St Gregory, St Ambrose, St Jerome and St Augustine, but their frivolous detail invoked letters of protest to their "Catholic" design.[3] When the Dean, Gilbert Elliot, heard of the controversy, he employed a team of workmen without the knowledge of the architect or committee to remove the statues.[3] The next edition of the Bristol Times reported that 'a more rough and open exhibition of iconoclasm has not been seen in Bristol since the days of Oliver Cromwell.' The sculptor, James Redfern, was made the scapegoat by the architect and the church, he retreated from the project, fell ill, and died later that year. As a result of Elliot's actions, the committee resigned en masse and the completion of the works was taken over by the Dean and Chapter. Elliot's drop in popularity meant that raising funds was a harder and slower process and the nave had to be officially opened before the two west towers were built.[3]

Several of the bells in the north-west tower were cast in 1887 by John Taylor & Co. However, earlier bells include those from the 18th century by the Bilbie family and one by William III & Richard II Purdue made in 1658.[28][29]

20th century

The full peal of 8 bells was installed in the north-west tower, taken from the ruins of Temple Church after the bombing of World War II.[30] In 1994 the ceremony took place in Bristol Cathedral for the first 32 women to be ordained as Church of England priests.[31] Since the early 2000s, the cathedral's associations with the legacy of philanthropist and enslaver Edward Colston have also been the subject of public debate resulting in changes to annual commemoration services and memorials inside the cathedral.[32]

Architecture

| Feature | Dimension |

|---|---|

| Total length, external | 300 feet (91 m) |

| Total length, internal | 284 feet (87 m) |

| Length of nave | 125 feet (38 m) |

| Width, including aisles | 69 feet (21 m) |

| Length of transept | 115 feet (35 m) |

| Width of transept | 29 feet (8.8 m) |

| Height to vault in nave | 52 feet (16 m) |

| Height to vault in choir | 50 feet (15 m) |

| Area | 22,556 square feet (2,095.5 m2) |

Bristol Cathedral is a grade I listed building which shows a range of architectural styles and periods.[1] Tim Tatton-Brown writes of the 14th century eastern arm as "one of the most interesting and splendid structures in this country".[34]

Specifications

Most of the medieval stonework, is made from limestone taken from quarries around Dundry and Felton with Bath stone being used in other areas. The two-bay Elder Lady Chapel, which includes some Purbeck Marble, lies to the north of the five-bay aisled chancel or presbytery. The Eastern Lady Chapel has two bays, the sacristy one-bay and the Berkeley Chapel two bays. The exterior has deep buttresses with finials to weathered tops and crenellated parapets with crocketed pinnacles below the Perpendicular crossing tower.[1]

The west front has two large flanking three-stage towers. On the rear outer corners of the towers are octagonal stair turrets with panels on the belfry stage. Between the towers is a deep entrance arch of six orders with decorative Purbeck Marble colonnettes and enriched mouldings to the arch. The tympanum of the arch contains an empty niche.[1]

Hall Church

The eastern end of Bristol Cathedral is highly unusual for a number of reasons. Firstly, it was conceived as a "hall church", meaning that the aisles are the same height as the choir. While a feature of German Gothic architecture, this is rare in Britain, and Bristol cathedral is the most significant example. In the 19th century, G. E. Street designed the nave along the same lines.[1] The effect of this elevation means that there are no clerestory windows to light the central space, as is usual in English Medieval churches. The north and south aisles employ a unique manner where the vaults rest on tie beam style bridges supported by pointed arches.[35] All the internal light must come from the aisle windows which are accordingly very large.[36] In the choir, the very large window of the Lady chapel is made to fill the entire upper part of the wall, so that it bathes the vault in daylight, particularly in the morning.[37]

Because of the lack of a clerestory, the vault is comparatively low, being only about half the height of that at Westminster Abbey. The interior of the cathedral appears wide and spacious. The architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner wrote of the early 14th-century choir of Bristol that "from the point of view of spatial imagination" it is not only superior to anything else in England or Europe but "proves incontrovertibly that English design surpasses that of all other countries" at that date.[38]

The choir has broad arches with two wave mouldings carried down the piers which support the ribs of the vaulting. These may have been designed by Thomas Witney or William Joy as they are similar to the work at Wells Cathedral and St Mary Redcliffe.[39] The choir is separated from the eastern Lady Chapel by a 14th-century reredos which was damaged in The reformation and repaired in 1839 when the 17th-century altarpiece was removed. The Lady Chapel was brightly painted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries following existing fragments of colour. To the south east of the choir and Lady Chapel is the Berkeley Chapel and an adjoining antechapel or sacristy, which may have been added in the 14th century, possibly replacing an earlier structure.[40]

Vaulting

Another feature of Bristol Cathedral is the vaulting of its various medieval spaces. The work that was carried out under Abbot Knowle is unique in this regard, with not one, but three unique vaults.[41]

In vaulting a roof space using stone ribs and panels of infill, the bearing ribs all spring from columns along the walls. There is commonly a rib called the ridge rib which runs along the apex of the vault. There may be intermediate or "tierceron" ribs, which have their origin at the columns.[42] In Decorated Gothic there are occasionally short lierne ribs connecting the bearing and tierceron ribs at angles, forming stellar patterns. This is the feature that appears at Bristol, at a very early date, and quite unlike the way that "lierne" ribs are used elsewhere. In this case, there is no ridge rib, and the lierne ribs are arranged to enclose a series of panels that extend the whole way along the centre of the choir roof, interacting with the large east window by reflecting the light from the smoothly arching surfaces. From the nave can be seen the intricate tracery of the east window echoed in the rich lierne pattern of the tower vault, which is scarcely higher than the choir, and therefore clearly visible. The two aisles of the choir both also have vaults of unique character, with open transverse arches and ribs above the stone bridges.[36]

East Lady Chapel

The 13th-century East Lady Chapel is built of red sandstone in an Early English style, making it stand out from the rest of the building. It is four bays long and has a vaulted ceiling. The windows are supported by Blue Lias shafts matching those between the bays. Much of the chapel, including the piscina and sedilia, is decorated with stylised foliage, in a style known as "stiff-leaf".[43]

Nave

Street's design followed the form of the Gothic choir. On a plan or elevation it is not apparent that the work is of a different era. But Street designed an interior that respected the delicate proportions of the ribs and mouldings of the earlier work, but did not imitate their patterns. Street's nave is vaulted with a conservative vault with tierceron ribs, rising at the same pitch as the choir.[44] Street's aisle vaults again echo their counterparts in the mediaeval chancel, using open vaulting above the stone bridges, but the transverse vaults are constructed differently.

Fittings

The cathedral has two unusual and often-reproduced monuments, the Berkeley memorials. These are set into niches in the wall, and each is surrounded by a canopy of inverted cusped arches. Pearson's screen, completed in 1905,[13] echoes these memorials in its three wide arches with flamboyant cusps.

West front

Unlike many English Gothic cathedrals, Bristol's west facade has a rose window above the central doorway. The details, however, are clearly English, owing much to the Early English Gothic at Wells Cathedral and the Decorated Gothic at York Minster with a French Rayonnant style.[45]

Chapter House

The late Norman chapter house, situated south of the transept,[1] contains some of the first uses of pointed arches in England.[46] It also has a rich sculptural decoration, with a variety of Romanesque abstract motifs.[47] In both of these aspects there are close similarities with the abbey gatehouse, supporting the view that the two structures were built around the same time in the 12th century, as put forward by Street in the 19th century.[46][48]

The approach to the chapter house is through a rib-vaulted ante-room 3 bays wide, whose pointed arches provide a solution to that room's rectangular shape. Carved pointed arches also appear in the decoration of the chapter house itself. Here they arise from the intersections of the interlaced semicircular arcading, which runs continuously around the walls. The chapter house has a quadripartite ribbed vault 7.5 metres (25 ft) high. The ribs, walls and columns display a complex interplay of carved patterns: chevron, spiral, nailhead, lozenge and zigzag.[49][50]

The chapter house has 40 sedilia lining its walls, and may have originally provided seating for more when it was the meeting room for the abbey community.[50] In 1714 it was refurbished to become a library, and its floor was raised by about 1 m (3 ft). Its east end was damaged in the Bristol riots of 1831, requiring considerable restoration, and at that time or later the library furnishings were removed. In 1832, when the floor was lowered again, a Saxon stone panel depicting the Harrowing of Hell was found underneath.[49] The discovery of the stone provides strong evidence that there was a church or shrine on the site before Robert Fitzharding founded the Abbey in 1140.[8]

Stained glass

The east window in the Lady Chapel was largely replaced and restored in the mid 19th century. However, it does contain some 14th-century stained glass pieces, including male heads and heraldic symbols.[51] Some of the early glass is also incorporated into the Tree of Jesse which goes across nine lights.[52][53]

During the restoration led by Street, most of the work on the glass was by Hardman & Co.; these include the rose window and towers at the west end and the Magnificat in the Elder Lady Chapel.[52]

Some of the most recent stained glass is by Bristolian Arnold Wathen Robinson following damage during the Bristol Blitz of 1940 and 1941. These included depictions of local Civil Defence during World War II including St. John Ambulance, the British Red Cross and the fire services along with air raid wardens, police officers, the Home Guard and the Women's Voluntary Service.[54] The most recent glass is an abstract expressionist interpretation of the Holy Spirit designed by Keith New in 1965 and installed in the south choir.[55]

A Victorian era window under the cathedral's clock, marked "to the glory of God and in memory of Edward Colston" and commemorating that 17th-century Royal African Company magnate and Bristol philanthropist, was ordered to be covered in June 2020 in advance of its eventual removal.[56][57] The Diocese of Bristol also decided to remove from the cathedral other dedications to Colston after the toppling of the late 19th-century Statue of Edward Colston in the city centre on 7 June 2020, along with the removal of another stained glass window at St Mary Redcliffe.[56] The cathedral dean previously considered removing the memorial window in 2017 but said in a radio broadcast in February it would cost "many, many thousands of pounds".[58][57] The legacy of Colston became contentious because of his involvement in, and profit from, the transatlantic slave trade in enslaved Africans, and came to a head after the killing of George Floyd in May 2020.[59][32]

Decoration, monuments and burials

The south transept contains the important late Saxon stone panel of the Harrowing of Hell. It dates from before the Norman Conquest and may have been carved around 1050. Following a fire in 1831 it was found being used as a coffin lid under the Chapter House floor.[13][60][61]

The high altar stone reredos are by John Loughborough Pearson of 1899. The three rows of choir stalls are mostly from the late 19th century with Flamboyant traceried ends. There are also 28 misericords dating from 1515 to 1526, installed by Robert Elyot, Abbot of St. Augustine's, with carvings largely based on Aesop's Fables.[62] In the Berkeley chapel is a very rare candelabrum of 1450 from the Temple church in Bristol.[63][64]

The monuments within the cathedral include recumbent figures and memorials of several abbots and bishops: Abbot Walter Newbery who died in 1473 and Abbot William Hunt (died 1481) are within 14th-century recesses on the north side of the Lady Chapel, while the recumbent effigy of Abbot John Newland (died 1515) is in a similar recess on the southern side. The coffin lid of Abbot David (died 1234) is in the north transept.[65] In the north choir aisle is a chest tomb to Bishop Bush (died 1558) which includes six fluted Ionic columns with an entablature canopy.[65] Also honoured are: Thomas Westfield, Bishop of Bristol (1642–1644), Thomas Howell (Bishop of Bristol) (1644–1645), Gilbert Ironside the elder, Bishop of Bristol (1661–1671), William Bradshaw (bishop), Bishop of Bristol (1724–1732), Joseph Butler, Bishop of Bristol (1738–1750), John Conybeare, Bishop of Bristol (1750–1755) and Robert Gray (bishop of Bristol) (1827–1834), who is buried in graveyard attached to the cathedral. The Berkeley family as early benefactors are represented by Maurice de Berkeley (died 1281), *Thomas de Berkeley, 1st Baron Berkeley (died 1321), Lord Berkeley (died 1326) and Thomas Berkeley (died 1243) who are depicted in military effigies on the south side of the choir aisle, along with the chest tomb of Maurice Berkeley (died 1368).

In addition there are notable monuments to local dignitaries of the 17th and 18th century. There is a perpendicular reredos showing figures kneeling at a prayer desk flanked by angels to Robert Codrington (died 1618) and his wife.[66] Phillip Freke (died 1729) is commemorated with a marble wall tablet in the north choir aisle. The oval wall tablet to Rowland Searchfield, English academic and Bishop of Bristol (died 1622) is made of slate.[1] The Newton Chapel, which is between the Chapter House and south choir aisle contains a large dresser tomb of Henry Newton (died 1599) and a recumbent effigy of John Newton (died 1661),[65] as well as a dresser tomb dedicated to Charles Vaughan who died in 1630.[67]

Dame Joan Wadham (1533–1603) is buried, with her two husbands Sir Giles Strangways and Sir John Young, in an altar tomb at the entrance to Bristol Cathedral. She was one of the sisters and co-heiresses (through her issue) of Nicholas Wadham (1531–1609) of Merryfield, Ilton Somerset and of Edge, Branscombe Devon, the co-founder with his wife Dorothy Wadham (1534–1618) of Wadham College, Oxford.[68]

Dame Joan is represented in effigy lying beneath the armorials of Wadham and those of both her husbands, Giles Strangways MP (1528–1562) of Melbury Sampford, with her the ancestor of the Earls of Ilchester, and John Young MP (1519–1589) with whom she built the Great House Bristol from 1568, of which only the Red Lodge, now the Red Lodge Museum, Bristol and completed by Dame Joan in 1590 after the death of her husband, remains today.[69]

Queen Elizabeth I stayed with Joan and Sir John Young at The Great House when she visited Bristol in 1574, and the Red Lodge Museum with its Tudor panelled rooms and wood carvings is only a short walk from the cathedral.[70]

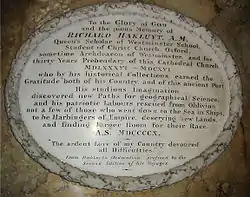

The importance of exploration and trade to the city are reflected by a memorial tablet and representation in stained glass of Richard Hakluyt (died 1616) is known for promoting the settlement of North America by the English through his works. He was a prebendary of the cathedral.[71]

More recent monuments from the early 18th century to the 20th century include: Mrs Morgan (died 1767) by John Bacon to the design of James Stuart and a bust by Edward Hodges Baily to Robert Southey a Bristolian poet of the Romantic school, one of the so-called "Lake Poets", and Poet laureate for 30 years from 1813 to his death in 1843. Baily also created the monument to William Brane Elwyn (died 1841). The obelisk to local actor William Powell (died 1769) was made by James Paine.[72] The memorial to Elizabeth Charlotte Stanhope (died 1816) in the Newton Chapel is by Richard Westmacott.[73] There is a memorial plaque to the education reformer Mary Carpenter (died 1877).[1] The memorial to Emma Crawfuird (died 1823) is by Francis Leggatt Chantrey while the effigy to Francis Pigou (Dean; died 1916) is by Newbury Abbot Trent.[1] The most recent are of the biographer Alfred Ainger (died 1904) and the composer Walford Davies (died 1941).

Dean and Chapter

As of 30 November 2020:[74]

- Dean — Mandy Ford (since 3 October 2020 installation)[75]

- Canon Precentor — Nicola Stanley (since 1 March 2014 installation)[76]

- Canon Chancellor — Michael Roden (since 12 January 2019 installation)[77]

- Diocesan Canon & Bishop's Chaplain — Martin Gainsborough (since 22 May 2019;[78] previously Diocesan Canon, 2016–2019)[79]

- Diocesan Canon — vacant since 1 January 2019 (most recently Gainsborough as Canon Theologian and Diocesan Social Justice and Environmental Adviser)

Music

Organ

The organ was originally built in 1685 by Renatus Harris at a cost of £500.[80] This has been removed and repaired many times. However, some of the original work, including the case and pipes, is incorporated into the present instrument, which was built by J. W. Walkers & Sons in 1907, to be found above the stalls on the north side of the choir. It was further restored in 1989.[81][82]

Prior to the building of the main organ, the cathedral had a chair organ, which was built by Robert Taunton in 1662,[83] and before that one built by Thomas Dallam in 1630.[84]

Organists

The earliest known appointment of an organist of Bristol Cathedral is Thomas Denny in 1542.[85] Notable organists have included the writer and composer Percy Buck and the conductor Malcolm Archer. The present Organist is Mark Lee and the Assistant Organist Paul Walton.[86]

Choirs

The first choir at Bristol probably dates from the Augustinian foundation of 1140. The present choir consists has twenty-eight choristers, six lay clerks and four choral scholars. The choristers include fourteen boys and fourteen girls, who are educated at Bristol Cathedral Choir School, the first government-funded choir academy in England. Choral evensong is sung daily during term.[87]

The Bristol Cathedral Concert Choir (formerly Bristol Cathedral Special Choir) was formed in 1954[88] and comprised sixty singers who presented large-scale works such as Bach's St Matthew Passion.;[87] it was wound up in 2016.[89] The Bristol Cathedral Consort is a voluntary choir drawn from young people of the city. They sing Evensong twice a month.[87] Bristol Cathedral Chamber Choir was reformed in 2001 and is directed by assistant organist Paul Walton.[87]

Burials in St Augustine's Abbey

- Harding of Bristol

- Robert Fitzharding and his wife Eva

- Maurice de Berkeley, Baron Berkeley

- Maurice de Berkeley, 4th Baron Berkeley

- Thomas de Berkeley, 1st Baron Berkeley

- Margaret Mortimer, Baroness Berkeley, wife of Thomas de Berkeley, 3rd Baron Berkeley

- William de Berkeley, 1st Marquess of Berkeley

In popular culture

Bristol Cathedral was used as a location in the 1978 film The Medusa Touch under the guise of a fictional London place of worship called Minster Cathedral.[90]

Other cathedrals in Bristol

Bristol is also home to a Roman Catholic cathedral, Clifton Cathedral. The Church of England parish church of St. Mary Redcliffe is so grand as to be occasionally mistaken for a cathedral by visitors.[91]

See also

Notes

- Historic England. "Cathedral Church of St Augustine, including Chapter House and cloisters (1202129)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Smith 1970, p. 6.

- J H Bettey, Bristol Cathedral the Rebuilding of the Nave, University of Bristol (Bristol branch of the Historical Association), 1993

- Walker 2001, pp. 12–18.

- "St Augustine's Abbey". University of the West of England. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- McNeill 2011, pp. 32–33.

- "Bristol Cathedral". Victoria County History. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- J H Bettey, St Augustine's Abbey Bristol, University of Bristol (Bristol branch of the Historical Association), 1996

- Page, William (ed.). "Houses of Augustinian canons: The abbey of St Augustine, Bristol". British History Online. Victoria County History. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- Harrison 1984, p. 2.

- Bettey 1996, pp. 1, 5, 7.

- Burrough 1970, p. 2.

- Historic England. "Bristol Cathedral (1007295)". PastScape. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- Ditchfield, P. H. (1902). The Cathedrals of Great Britain. J.M. Dent. p. 138. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014.

- "Elder Lady Chapel". Bristol Cathedral. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- Hendrix 2012, p. 132.

- Godwin 1863, pp. 38–63.

- "Bristol: Introduction Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1541–1857: Volume 8, Bristol, Gloucester, Oxford and Peterborough Dioceses". British History Online. Institute of Historical Research. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- Nicholls & Taylor "Bristol Past & Present" 3vols. 1881

- Bettey 1996, pp. 7, 11–15, 21, 24–5.

- "Photo of plaque commemorating William Phillips' actions". Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- "No. 19426". The London Gazette. 7 October 1836. pp. 1734–1738.

- "No. 26871". The London Gazette. 9 July 1897. p. 3787.

- "George Edmund Street". Architecture.com. Royal Institute of British Architects. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- "Bristol Cathedral". Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. 24 October 1877. Retrieved 10 March 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "Brief History". Bristol Cathedral. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- Bettey & Harris 1993.

- Moore, Rice & Hucker 1995.

- "Bristol Cathedral Church of the Holy & Undivided Trinity". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- "Bells and Bellringing - Bristol Cathedral". bristol-cathedral.co.uk. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- "The women priests debate". Church of England. Archived from the original on 26 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- Richards, Samuel J. (September 2020). "Historical Revision in Church: Re-examining the 'Saint' Edward Colston". Anglican and Episcopal History. 89 (3): 225–254.

- "Bristol Cathedral". Time Ref. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- Tatton-Brown & Cook 2002.

- David Pepin, Discovering Cathedrals, Osprey Publishing, 2004

- Clifton-Taylor 1967, pp. 191–192.

- Masse 1901, p. 40.

- Pevsner 1958, pp. 371–386.

- Foyle 2004, pp. 52–54.

- Foyle 2004, pp. 53–56.

- Burrough 1970, pp. 9–11.

- Foyle 2004, pp. 53–54.

- Foyle 2004, pp. 52–53.

- Foyle 2004, pp. 56–57.

- Cannon, Jon. "Bristol Cathedral — architectural overview". Bristol Cathedral. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- Gomme, Jenner & Little 1979, pp. 17–18.

- Foyle 2004, p. 62.

- Oakes 2000, pp. 85–86.

- Oakes 2000, pp. 78–83.

- Sivier 2002, pp. 125–127.

- "Panel of the Month Veiled Manhood in the Lady Chapel at Bristol". Vidimus. 21. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- Foyle 2004, pp. 58–59.

- "The east window". The Rose Window. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- "Footsteps into the Past: Memorial windows, Bristol Cathedral". Bristol Post. 11 November 2014. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- Smith 1983, pp. 14–15.

- "Church windows celebrating slave trader removed". BBC News. 16 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "'Slavery' window removal considered". BBC News. 23 February 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- James, Aaron (20 February 2017). "Bristol Cathedral open to removing Colston window amid slavery concerns". Premier Christian News (premierchristian.news). Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Protesters tear down statue amid anti-racism demos". BBC News. 8 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "South Transept". Bristol Cathedral. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- Smith, M. Q. (1976). "The Harrowing of Hell Relief in Bristol Cathedral" (PDF). Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society. 94: 101–106. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2015.

- Perry, Mary Phillips (1921). "The Stall Work of Bristol Cathedral" (PDF). Archaeological Journal. 78 (1): 233–250. doi:10.1080/00665983.1921.10853369. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Burrough 1970, p. 11.

- "Holy Cross (Temple Church)". Church Crawler. Archived from the original on 17 May 2005. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- Foyle 2004, p. 60.

- "Bristol". Church Monuments Society. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- "VAUGHAN, Sir Charles (1584–1631), of Falstone House, Bishopstone, Wilts". The History of Parliament. The History of Parliament Trust. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- See pedigree of Wadham, pages 27–28, Wadham College Oxford Its Foundation Architecture And History With An Account Of Wadham And Their Seats In Somerset And Devon by T.G. Jackson, Oxford at The Clarendon Press

- Maclean, John (1890). "The Family of Young, of Bristol, and on the Red Lodge" (PDF). Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society. 15: 227–245. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016.

- "Young's Great House". Bristol Museums Galleries and Archives. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- Quinn, David B. (1974). The Hakluyt Handbook. Cambridge University Press. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-521-08694-3.

- Howard Colvin (1978). A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects 1600–1840. John Murray. pp. 612–613. ISBN 978-0-7195-3328-0.

- Britton, John; Le Keux, John; Blore, Edward (1836). Peterborough, Gloucester, and Bristol. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green, and T. Longman. p. 64.

- "Who we are - Bristol Cathedral". Bristol-cathedral.co.uk. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- "Diocese of Bristol | Installation of the Revd Canon Dr Mandy Ford as Dean of Bristol marks a first for the Church of England". Bristol.anglican.org. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- "Week 1 - Nicola Stanley - Bristol Cathedral". Bristol-cathedral.co.uk. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Diocese of Bristol | Martin Gainsborough announced as Residentiary Canon at Bristol Cathedral". Bristol.anglican.org. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Crotchet, Dotted (November 1907). "Bristol Cathedral". Musical Times. The Musical Times, Vol. 48, No. 777. 48 (777): 705–715. doi:10.2307/904456. JSTOR 904456.

- "Organ". Bristol Cathedral. Archived from the original on 19 January 2007. Retrieved 28 June 2007.

- "Bristol Cathedral". Bristol Link. Archived from the original on 5 July 2007. Retrieved 28 June 2007.

- "Letters to the editor — July 1981". British Institute of Organ Studies (BIOS). Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2007.

- Lehmberg 1996, p. 4.

- "The Bristol Cathedral Choir". Meridian Records. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- "Who we are". Bristol Cathedral. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- Bristol Cathedral Choirs Archived 6 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 1 March 2013

- "Diamond Jubilee Concert 2014". Bristol Cathedral. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- "Charity details". Charity Commission. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- "The Medusa Touch". Bristol Cathedral. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Bristol Cathedral". Open Buildings. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

Bibliography

- Bettey, Joseph H. (1996). St.Augustine's Abbey Bristol. Historical Association (Bristol Branch). ISBN 978-0901388728.

- Bettey, Joseph H.; Harris, Peter (1993). Bristol Cathedral: The Rebuilding of the Nave. Historical Assn.(Bristol). ISBN 978-0901388667.

- Burrough, THB (1970). Bristol. London: Studio Vista. ISBN 978-0289798041.

- Clifton-Taylor, Alec (1967). The Cathedrals of England (2 ed.). Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0500200629.

- Foyle, Andrew (2004). Pevsner Architectural Guide, Bristol. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300104424.

- Godwin, Edward W. (1863). "Bristol Cathedral" (PDF). The Archaeological Journal. 20: 38–63. doi:10.1080/00665983.1863.10851241.

- Gomme, A.; Jenner, M.; Little, B. (1979). Bristol: an architectural history. London: Lund Humphries. ISBN 978-0853314097.

- Harrison, D. E. W. (1984). Bristol Cathedral. Heritage House Group. ISBN 978-0851012322.

- Hendrix, John Shannon (2012). The Splendor of English Gothic Architecture. Parkstone International. ISBN 9781780428918.

- Lehmberg, Stanford E. (1996). Cathedrals Under Siege: Cathedrals in English Society, 1600–1700. Penn State Press. ISBN 9780271044200.

- Masse, H. J. L. J. (1901). The Cathedral Church of Bristol. George Bell & Sons.

- McNeill, John (2011). "The Romanesque Fabric". In Cannon, Jon; Williamson, Beth (eds.). The Medieval Art, Architecture and History of Bristol Cathedral: An Enigma Explored. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1843836803. ASIN 1843836807.

- Moore, James; Rice, Roy; Hucker, Ernest (1995). Bilbie and the Chew Valley clock makers. The authors.

- Oakes, Catherine (2000). Rogan, John (ed.). Bristol Cathedral: History and Architecture. Charleston: Tempus. ISBN 978-0752414829.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1958). North Somerset and Bristol. Penguin Books. OCLC 868291293.

- Richards, Samuel J. (September 2020). "Historical Revision in Church: Re-examining the "Saint" Edward Colston". Anglican and Episcopal History. 89 (3): 225–254.

- Sivier, David (2002). Anglo-Saxon and Norman Bristol. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus. ISBN 978-0752425337.

- Smith, M.Q. (1970). The medieval churches of Bristol. Historical Association (Bristol Branch). ISBN 978-0901388025.

- Smith, M.Q. (1983). The Stained Glass of Bristol Cathedral. Redcliffe Press. ISBN 978-0905459714.

- Tatton-Brown, T .W. T.; Cook, John (2002). The English Cathedral. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 978-1843301202.

- Walker, David (2001). Bettey, Joseph (ed.). Historic Churches and Church Life in Bristol. Bristol: Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society. ISBN 978-0900197536.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bristol Cathedral. |