Rebus

A rebus (/ˈriːbəs/) is a puzzle device that combines the use of illustrated pictures with individual letters to depict words or phrases. For example: the word "been" might be depicted by a rebus showing an illustrated bumblebee next to a plus sign (+) and the letter "n". It was a favourite form of heraldic expression used in the Middle Ages to denote surnames.

For example, in its basic form, three salmon (fish) are used to denote the surname "Salmon". A more sophisticated example was the rebus of Bishop Walter Lyhart (d. 1472) of Norwich, consisting of a stag (or hart) lying down in a conventional representation of water.

The composition alludes to the name, profession or personal characteristics of the bearer, and speaks to the beholder Non verbis, sed rebus, which Latin expression signifies "not by words but by things"[1] (res, rei (f), a thing, object, matter; rebus being ablative plural).[2]

Rebuses within heraldry

Rebuses are used extensively as a form of heraldic expression as a hint to the name of the bearer; they are not synonymous with canting arms. A man might have a rebus as a personal identification device entirely separate from his armorials, canting or otherwise. For example, Sir Richard Weston (d. 1541) bore as arms: Ermine, on a chief azure five bezants, whilst his rebus, displayed many times in terracotta plaques on the walls of his mansion Sutton Place, Surrey, was a "tun" or barrel, used to designate the last syllable of his surname.

An example of canting arms proper are those of the Borough of Congleton in Cheshire consisting of a conger eel, a lion (in Latin, leo) and a tun (barrel). This word sequence "conger-leo-tun" enunciates the town's name. Similarly, the coat of arms of St. Ignatius Loyola contains wolves (in Spanish, lobo) and a kettle (olla), said by some (probably incorrectly) to be a rebus for "Loyola". The arms of Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon feature bows and lions.

Modern rebuses, word plays

A modern example of the rebus used as a form of word play is:

- H +

= Hear, or Here.

= Hear, or Here.

By extension, it also uses the positioning of words or parts of words in relation to each other to convey a hidden meaning, for example:

- p walk ark: walk in the park.

A rebus made up solely of letters (such as "CU" for "See you") is known as a gramogram, grammagram, or letteral word. This concept is sometimes extended to include numbers (as in "Q8" for "Kuwait", or "8" for "ate").[3] Rebuses are sometimes used in crossword puzzles, with multiple letters or a symbol fitting into a single square.[4]

Pictograms

The term rebus also refers to the use of a pictogram to represent a syllabic sound. This adapts pictograms into phonograms. A precursor to the development of the alphabet, this process represents one of the most important developments of writing. Fully developed hieroglyphs read in rebus fashion were in use at Abydos in Egypt as early as 3400 BCE.[5] In Mesopotamia, the principle was first employed on proto-cuneiform tablets, beginning in the Jemdet Nasr period (c. 3100–2900 BC).[6][7]

The writing of correspondence in rebus form became popular in the 18th century and continued into the 19th century. Lewis Carroll wrote the children he befriended picture-puzzle rebus letters, nonsense letters, and looking-glass letters, which had to be held in front of a mirror to be read.[8] Rebus letters served either as a sort of code or simply as a pastime.

Rebus principle

In linguistics, the rebus principle is the use of existing symbols, such as pictograms, purely for their sounds regardless of their meaning, to represent new words. Many ancient writing systems used the rebus principle to represent abstract words, which otherwise would be hard to represent with pictograms. An example that illustrates the Rebus principle is the representation of the sentence "I can see you" by using the pictographs of "eye—can—sea—ewe".

Some linguists believe that the Chinese developed their writing system according to the rebus principle,[9] and Egyptian hieroglyphs sometimes used a similar system. A famous rebus statue of Ramses II uses three hieroglyphs to compose his name: Horus (as Ra), for Ra; the child, mes; and the sedge plant (stalk held in left hand), su; the name Ra-mes-su is then formed.[10]

Freud[11] posited that the rebus was the basis for uncovering the latent content of the dream. He wrote, "A dream is a picture puzzle of this sort and our predecessors in the field of dream interpretation have made the mistake of treating the rebus as a pictorial composition: and as such it has seemed to them nonsensical and worthless."

Use in game shows

Canada

- 1980s children's game show Kidstreet featured a rebus during the bonus round (or "final lap").

United Kingdom

- Catchphrase is a long-running game show which required contestants to decipher a rebus. The show began as a short-lived American game show hosted by Art James before being seen in the United Kingdom from 1986 to 2004 and returning in 2013. There was also an Australian version of the show hosted by John Burgess.

- In 1998, Granada TV produced Waffle, a single word rebus puzzle show that was hosted by Nick Weir, and included premium telephone line viewer participation.

United States

- Rebuses were central to the television game show Concentration. Contestants had to solve a rebus, usually partially concealed behind any of thirty "squares", to win a game. An updated version, known as Classic Concentration, shrank the board to twenty-five squares. There were also British and Australian versions of the game.

- The HBO children's game series Crashbox features three rebus puzzles in the game segment "Ten Seconds."

- A short-lived ABC game show from 1965 known as The Rebus Game also involved contestants creating rebuses to communicate an answer.

India

- Dadagiri Unlimited is a game show in which some rebus puzzles are used in the googly round. The show is broadcast by Zee Bangla and hosted by the former Indian cricketer Sourav Ganguly.

Historical examples

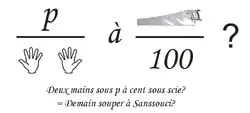

- It is reported[13] that when Voltaire was the guest of Frederick the Great at Sanssouci Palace, they exchanged puzzle notes. Frederick sent over a page with two picture blocks on it: two hands below the letter P, and then the number 100 below a picture of a handsaw, all followed by a question mark. Voltaire replied with: Ga!

- Both messages were rebuses in the French language: deux mains sous Pé à cent sous scie? "two hands under 'p' at [one] hundred under saw" = demain souper à Sanssouci? "supper tomorrow at Sanssouci?"); reply: Gé grand, A petit! "big 'G', small 'a'!" (= j'ai grand appétit! "I am very hungry!").

- The early 16th-century Bishop of Exeter, Hugh Oldham, adopted the owl as his personal device. It bore a scroll in its beak bearing the letters D.O.M., forming a rebus based on his surname, which would probably have been pronounced at the time as owl-dom.[14]

- The 19th-century French sculptor Jean-Pierre Dantan would place rebuses on the socles of his caricature busts to identify the subject. For example, Victor Hugo was an axe (hache in French, which sounds like the French pronunciation of "H") + UG + crossed bones (os, sounding like "O"). Hector Berlioz was represented by the letters BER low on the socle, with a bed (lit, for "li") comparatively high on the socle (to mean "haut", the French for high, pronounced with a silent "h" and "t" and so sounding like "O").[15]

- Rebus Bibles such as A Curious Hieroglyphic Bible were popular in the late 18th century for teaching Bible-reading to children.[16]

- Franciscans interacting with Nahuatl-speaking groups found that the Cholultecans used rebus principles to record information in Latin. The Cholultecans learned the Pater Noster or Lord's Prayer with the aid of drawing pictures of a pantli (flag or banner) to represent pater and a picture of a prickly pear, nochtli, for noster. This practice was seen as a strength of the people's pictograhic literacy.[17]

Japan

In Japan, the rebus known as hanjimono (判じ物)[18] was immensely popular during the Edo period.[19] A piece by ukiyo-e artist Kunisada was "Actor Puzzles" (Yakusha hanjimono) that featured rebuses.[20]

Today the most often seen of these symbols is a picture of a sickle, a circle, and the letter nu (ぬ), read as kama-wa-nu (鎌輪ぬ, sickle circle nu), interpreted as kamawanu (構わぬ), the old-fashioned form of kamawanai (構わない, don't worry, doesn't matter). This is known as the kamawanu-mon (鎌輪奴文, kamawanu sign), and dates to circa 1700,[21] being used in kabuki since circa 1815.[22][23]

Kabuki actors would wear yukata and other clothing whose pictorial design, in rebus, represented their Yagō "guild names", and would distribute tenugui cloth with their rebused names as well. The practice was not restricted to the acting profession and was undertaken by townsfolk of various walks of life. There were also pictorial calendars called egoyomi that represented the Japanese calendar in rebus so it could be "read" by the illiterate.

Today a number of abstract examples following certain conventions are occasionally used for names, primarily for corporate logos or product logos and incorporating some characters of the name, as in a monogram; see Japanese rebus monogram. The most familiar example globally is the logo for Yamasa soy sauce, which is a ∧ with a サ under it. This is read as Yama, for yama (山, mountain) (symbolized by the ∧) + sa (サ, katakana character for sa).

Rebus puzzles on US beers

- Lone Star has rebus puzzles under the crown caps of its bottled beer, as do National Bohemian, Lucky Lager, Falstaff, Olympia, Rainier, Haffenreffer, IBM, Kassel, Pearl, Regal, Ballantine, Mickey's, Lionshead, and Texas Pride during the 1970s and the 1980s. These puzzle caps are also called "crown ticklers".[24] Narragansett Beer uses rebus puzzles on their bottle caps, and bar coasters.[25]

See also

References

- Boutell, Charles, Heraldry Historical & Popular, London, 1863, pp. 117–120

- Cassell's Latin Dictionary, ed. Marchant & Charles

- "Cryptic crossword reference lists > Gramograms". Highlight Press. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- Deb Amlen. "How to Solve The New York Times Crossword". New York Times. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Fischer, Steven Roger, "A History of Writing", 2004, Reaktion Books, ISBN 1-86189-167-9, ISBN 978-1-86189-167-9, at page 36

- DeFrancis, John (1989). Visible Speech: The Diverse Oneness of Writing Systems. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-8248-1207-2.

- Woods, Christopher (2010). "The earliest Mesopotamian writing". In Woods, Christopher (ed.). Visible language. Inventions of writing in the ancient Middle East and beyond (PDF). Oriental Institute Museum Publications. 32. Chicago: University of Chicago. pp. 33–50. ISBN 978-1-885923-76-9.

- Dawn Comer (3 January 1998). "Lewis Carroll Centenary Article". Niles Daily Star. Archived from the original on 13 May 2007.

- The Languages of China. S. Robert Ramsey. Princeton University Press, 1987, p. 137.

- The pharaohs. Ziegler, Christiane. London: Thames & Hudson. 2002. ISBN 9780500051191. OCLC 50215544.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Freud, S. (1900) The Interpretation of Dreams London: Hogarth Press

- Boutell, Charles (1863). Heraldry, Historical and Popular (2nd ed.). London: Winsor and Newton. p. 118.

- Danesi, Marcel (2002). The Puzzle Instinct: The Meaning of Puzzles in Human Life (1st ed.). Indiana, USA: Indiana University Press. p. 61. ISBN 0253217083.

- Moss, John. "Manchester Celebrities – Philanthropy, Philosophy & Religion – Bishop Hugh Oldham". ManchesterUK. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- "The Art Tribune – Jean-Pierre Dantan (1800–1869), Louis-Hector Berlioz, 1833". Thearttribune.com. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- "A Curious Hieroglyphick Bible". American Treasures of the Library of Congress. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- Mendieta, G. de (1971). Historia Eclesiastica Indiana[A religios History of the Indians]. Mexico, DF: Editorial Porrua (Original work published 1945)

- Hepburn, James Curtis (1873). A Japanese-English and English-Japanese Dictionary. A.D.F. Randolph.

- Ihara, Saikaku (1963). Morris, Ivan (ed.). The Life of an Amorous Woman: And Other Writings. A.D.F. Randolph. ISBN 978-0-8112-0187-2., p.348, note 456,

- Izzard, Sebastian; Rimer, J. Thomas; Carpenter, John T. (1993). Kunisada's world. Japan Society, in collaboration with Ukiyo-e Society of America. ISBN 978-0-913304-37-2., p. 23

- "辞典・百科事典の検索サービス - Weblio辞書". Arquivo.pt. Archived from the original on 25 May 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- Archived 17 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "旅から旅 文様事典 BBS". Tabikaratabi.pro.tok2.com. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- Alan J. Switzer. "Puzzle Beer Caps". Jokelibrary.net. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- "Rebus Puzzles". Narragansett Beer.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rebus. |

- How to solve Rebus puzzles.

- An example of using chinese-like characters to write English.

- The online music review La Folia offers rebuses derived from composers' names

- Online rebus generators, automatically convert any text into a rebus:

- festisite.com

- rebus.club High quality generator due to the use of a special purpose Edit distance algorithm.

- rebus1.com.

- Collection of interesting Rebus Puzzles