Buhen

Buhen (Ancient Greek: Βοὥν Bohón)[1] was an ancient Egyptian settlement situated on the West bank of the Nile below (to the North of) the Second Cataract in what is now Northern State, Sudan. It is now submerged in Lake Nasser, Sudan. On the East bank, across the river, there was another ancient settlement, where the town of Wadi Halfa now stands. The earliest mention of Buhen comes from stelae dating to the reign of Senusret I.[2] Buhen is also the earliest known Egyptian settlement in the land of Nubia.[3]

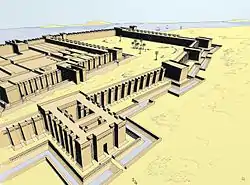

.jpg.webp) Fortress of Buhen, of the Middle Kingdom, reconstructed under the New Kingdom (about 1200 B.C.) | |

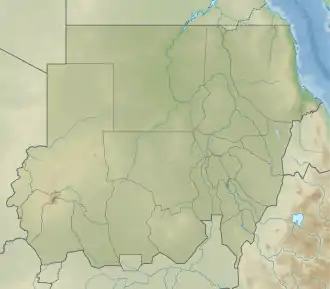

Shown within Northeast Africa  Buhen (Sudan) | |

| Location | Northern, Sudan |

|---|---|

| Region | Old Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 21°55′N 31°17′E |

| Type | Settlement |

Old Kingdom

| b(w)hn[4][1] in hieroglyphs |

|---|

| bwhn[4][1] in hieroglyphs |

|---|

In the Old Kingdom (about 2686–2181 BCE), Buhen was the site of a small trading post in Nubia that was also used for copper working.[5] The settlement may have been established during the reign of Sneferu (4th Dynasty). Nevertheless, there is evidence of still earlier, 2nd Dynasty, occupation at Buhen.[6][7]

An archaeological investigation in 1962 revealed what was described as an ancient copper factory.[3]

Graffiti and other inscribed items from the site show that the Egyptians stayed about 200 years, until late in the 5th Dynasty, when they were probably forced out by immigration from the south.

Fortress

Buhen is known for its large fortress, probably constructed during the rule of Senusret III in around 1860 BCE (12th Dynasty).[8] Senusret III conducted four campaigns into Kush and established a line of forts within signaling distance of one another; Buhen was the northernmost of these. The other forts along the banks were Mirgissa, Shalfak, Uronarti, Askut, Dabenarti, Semna, and Kumma. The Kushites captured Buhen during the 13th Dynasty, and held it until Ahmose I recaptured it at the beginning of the 18th Dynasty. It was stormed and recaptured by indigenous forces at the end of Egypt's 20th Dynasty.

The fortress itself extended more than 150 metres (490 ft) along the west bank of the Nile. It covered 13,000 square metres (140,000 sq ft), and had within its wall a small town laid out in a grid system. At its peak it probably had a population of around 3,500 people. The fortress also included the administration for the whole fortified region of the Second Cataract. Its fortifications included a moat three meters deep, drawbridges, bastions, buttresses, ramparts, battlements, loopholes, and a catapult. The outer wall included an area between the two walls pierced with a double row of arrow loops, allowing both standing and kneeling archers to fire at the same time.[8] The walls of the fort were about 5 metres (16 ft) thick and 10 metres (33 ft) high.[8] The walls of Buhen were crafted with rough stone.[9] The walls of Buhen are unique as most Egyptian fortress walls were constructed with timber and mud-brick.[9] The fortress at Buhen is now submerged under Lake Nasser as a result of the construction of the Aswan Dam in 1964. Before the site was covered with water, it was excavated by a team led by Walter Bryan Emery.

Buhen had a temple of Horus built by Hatshepsut, which was moved to the National Museum of Sudan in Khartoum prior to the flooding of Lake Nasser.

Copper Work at Buhen

During 1962, an archaeological expedition of Buhen took place revealing a copper factory.[3] During the excavation an unknown ore was found and analyzed further using modern techniques. The ore was originally made up of malachite however has become atacamite mixed with gold.[3] With many factors going into a location being adequate for copper smelting, Buhen would have been an ideal location to produce small quantities of copper.[3] An Egyptian device called, "Fire Dogs," were used to generally prepare food.[10] The exact usage of a fire dog is not known however, there is evidence that fire dogs involved fire and burning.[10] A large number of fire dogs were found a Buhen, this discovery has been associated with the potential generation of copper by using fire dogs.[10]

In order for a copper to be smelted in an area certain resources were necessary, and the availability of these resources determined if an area was suitable to copper smelting.[3] These resources included human labor, water, clay, wood, a mineral-based flux, and large quantities of the ore.[3] The mineral-based flux would be used to produce fluid slag during smelting. With Buhen's geographical location, during the time of the Old Kingdom, it would have met all of the requirements for a successful copper smelting location. Buhen is close in proximity to the Nile river, which would have provided the necessary supply water as well as clay.[11] With Egypt having a many skilled workers, a sufficient amount of the skilled workers necessary could have been brought to Buhen.[3] Although now there is not much evidence of sufficient timber, during the Old Kingdom a higher level of rainfall would have resulted in a larger availability to timber along the Nile and Wadis.[3] The slags stemming from the factory contain iron, indicative of a ferruginous flux.[3] This specific flux requires iron oxide, which is abundant throughout the Nile valley.[3] Despite evidence for the majority of the requirements, when it comes to the copper that would have been used for smelting not much is known about the source. All copper deposits recorded in Egypt and in Northern Sudan are long from Buhen.[3] All of these deposits are also located on the eastern side of the Nile, which poses further complications in transporting the copper that would have been smelted as it would have had to cross the Nile.[12]

Gallery

.jpg.webp) The Horus temple of Buhen in the Sudan National Museum

The Horus temple of Buhen in the Sudan National Museum A view of the fortress from the north (artist's impression)

A view of the fortress from the north (artist's impression)

Notes

- Wallis Budge, E. A. (1920). An Egyptian hieroglyphic dictionary: with an index of English words, king list and geological list with indexes, list of hieroglyphic characters, coptic and semitic alphabets, etc. Vol II. John Murray. p. 980.

- Randall-MacIver, David; Woolley, Sir Leonard (1911). Buhen. University Museum.

- Gayar, El Sayed El; Jones, M. P. (1989). "A Possible Source of Copper Ore Fragments Found at the Old Kingdom Town of Buhen". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 75: 31–40. doi:10.2307/3821897. JSTOR 3821897.

- Gauthier, Henri (1925). Dictionnaire des Noms Géographiques Contenus dans les Textes Hiéroglyphiques Vol. 2. p. 26.

- Buhen University College London

- Brian Yare, The Middle Kingdom Egyptian Fortresses in Nubia. 2001

- Drower, Margaret 1970: Nubia, A Drowning Land, London, pp. 16-17

- Lewis, Leo Richard; Tenney, Charles R. (2010). The Compendium of Weapons, Armor & Castles. Nabu Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-1146066846.

- Lawrence, A. W. (1965). "Ancient Egyptian Fortifications". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 51: 69–94. doi:10.2307/3855621. ISSN 0307-5133. JSTOR 3855621.

- Budka, Julia; Doyen, Florence (2012). "Life in New Kingdom Towns in Upper Nubianew Evidence from Recent Excavations on Sai Island". Ägypten und Levante / Egypt and the Levant. 22/23: 167–208. ISSN 1015-5104. JSTOR 43552818.

- Stanley, Daniel Jean; Wingerath, Jonathan G. (1996). "Clay Mineral Distributions to Interpret Nile Cell Provenance and Dispersal: I. Lower River Nile to Delta Sector". Journal of Coastal Research. 12 (4): 911–929. ISSN 0749-0208.

- Lucas, A. (1927). "Copper in Ancient Egypt". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 13 (3/4): 162–170. doi:10.2307/3853955. ISSN 0307-5133.