Provenance

Provenance (from the French provenir, 'to come from/forth') is the chronology of the ownership, custody or location of a historical object.[1] The term was originally mostly used in relation to works of art but is now used in similar senses in a wide range of fields, including archaeology, paleontology, archives, manuscripts, printed books, the circular economy, and science and computing.

The primary purpose of tracing the provenance of an object or entity is normally to provide contextual and circumstantial evidence for its original production or discovery, by establishing, as far as practicable, its later history, especially the sequences of its formal ownership, custody and places of storage. The practice has a particular value in helping authenticate objects. Comparative techniques, expert opinions and the results of scientific tests may also be used to these ends, but establishing provenance is essentially a matter of documentation. The term dates to the 1780s in English. Provenance is conceptually comparable to the legal term chain of custody.

For museums and the art trade, in addition to helping establish the authorship and authenticity of an object, provenance has become increasingly important in helping establish the moral and legal validity of a chain of custody, given the increasing amount of looted art. These issues first became a major concern regarding works that had changed hands in Nazi-controlled areas in Europe before and during World War II. Many museums began compiling pro-active registers of such works and their history. Recently the same concerns have come to prominence for works of African art, often exported illegally, and antiquities from many parts of the world, but currently especially in Iraq, and then Syria.[2]

In archaeology and paleontology, the derived term provenience is used with a related but very particular meaning, to refer to the location (in modern research, recorded precisely in three dimensions) where an artifact or other ancient item was found.[3] Provenance covers an object's complete documented history. An artifact may thus have both a provenience and a provenance.

Works of art and antiques

The provenance of works of fine art, antiques and antiquities is of great importance, especially to their owner. There are a number of reasons why painting provenance is important, which mostly also apply to other types of fine art. A good provenance increases the value of a painting, and establishing provenance may help confirm the date, artist and, especially for portraits, the subject of a painting. It may confirm whether a painting is genuinely of the period it seems to date from. The provenance of paintings can help resolve ownership disputes. For example, provenance between 1933 and 1945 can determine whether a painting was looted by the Nazis. Many galleries are putting a great deal of effort into researching the provenance of paintings in their collections for which there is no firm provenance during that period.[4] Documented evidence of provenance for an object can help to establish that it has not been altered and is not a forgery, a reproduction, stolen or looted art. Provenance helps assign the work to a known artist, and a documented history can be of use in helping to prove ownership. An example of a detailed provenance is given in the Arnolfini portrait.

The quality of provenance of an important work of art can make a considerable difference to its selling price in the market; this is affected by the degree of certainty of the provenance, the status of past owners as collectors, and in many cases by the strength of evidence that an object has not been illegally excavated or exported from another country. The provenance of a work of art may vary greatly in length, depending on context or the amount that is known, from a single name to an entry in a scholarly catalogue some thousands of words long.

An expert certification can mean the difference between an object having no value and being worth a fortune. Certifications themselves may be open to question. Jacques van Meegeren forged the work of his father Han van Meegeren (who in his turn had forged the work of Vermeer). Jacques sometimes produced a certificate with his forgeries stating that a work was created by his father.

John Drewe was able to pass off as genuine paintings, a large number of forgeries that would have easily been recognised as such by scientific examination. He established an impressive (but false) provenance and because of this galleries and dealers accepted the paintings as genuine. He created this false provenance by forging letters and other documents, including false entries in earlier exhibition catalogues.[5]

Sometimes provenance can be as simple as a photograph of the item with its original owner. Simple yet definitive documentation such as that can increase its value by an order of magnitude, but only if the owner was of high renown. Many items that were sold at auction have gone far past their estimates because of a photograph showing that item with a famous person. Some examples include antiques owned by politicians, musicians, artists, actors, etc.[6]

Researching the provenance of paintings

The objective of provenance research is to produce a complete list of owners (together, where possible, with the supporting documentary proof) from when the painting was commissioned or in the artist's studio through to the present time. In practice, there are likely to be gaps in the list and documents that are missing or lost. The documented provenance should also list when the painting has been part of an exhibition and a bibliography of when it has been discussed (or illustrated) in print.

Where the research is proceeding backwards, to discover the previous provenance of a painting whose current ownership and location is known, it is important to record the physical details of the painting – style, subject, signature, materials, dimensions, frame, etc.[7] The titles of paintings and the attribution to a particular artist may change over time. The size of the work and its description can be used to identify earlier references to the painting. The back of a painting can contain significant provenance information. There may be exhibition marks, dealer stamps, gallery labels and other indications of previous ownership. There may also be shipping labels. In the BBC TV programme Fake or Fortune? the provenance of the painting Bords de la Seine à Argenteuil was investigated using a gallery sticker and shipping label on the back. Early provenance can sometimes be indicated by a cartellino (a trompe-l'œil representation of an inscribed label) added to the front of a painting.[8] However, these can be forged, or can fade or be painted over.

Auction records are an important resource to assist in researching the provenance of paintings.

- The Witt Library houses a collection of cuttings from auction catalogs which enables the researcher to identify occasions when a picture has been sold.

- The Heinz Library at the National Portrait Gallery, London maintains a similar collection, but restricted to portraits.

- The National Art Library at the Victoria and Albert Museum has a collection of UK sales catalogues.[9]

- The University of York is establishing a web site with on-line resources for investigating art history in the period 1660–1735.[10] This includes diaries, sales catalogues, bills, correspondence and inventories.

- The Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles has a Project for the Study of Collecting and Provenance (PSCP) which includes an on-line database, still being compiled, of auction and other records relating to painting provenance.[11]

- The Frick Art Reference Library in New York has an extensive collection of auction and exhibition catalogues.[12]

- The Netherlands Institute for Art History (RKD) has a number of databases related to artists from the Netherlands.[13]

If a painting has been in private hands for an extended period and on display in a stately home, it may be recorded in an inventory – for example, the Lumley inventory.[14] The painting may also have been noticed by a visitor who subsequently wrote about it. It may have been mentioned in a will or a diary. Where the painting has been bought from a dealer, or changed hands in a private transaction, there may be a bill of sale or sales receipt that provides evidence of provenance. Where the artist is known, there may be a catalogue raisonné listing all the artist's known works and their location at the time of writing. A database of catalogues raisonnés is available at the International Foundation for Art Research. Historic photos of the painting may be discussed and illustrated in a more general work on the artist, period or genre. Similarly, a photograph of a painting may show inscriptions (or a signature) that subsequently became lost as a result of overzealous restoration. Conversely, a photograph may show that an inscription was not visible at an earlier date. One of the disputed aspects of the "Rice" portrait of Jane Austen concerns apparent inscriptions identifying artist and sitter.[15]

Archives

Provenance – also known as "custodial history" – is a core concept within archival science and archival processing. The term refers to the individuals, groups, or organizations that originally created or received the items in an accumulation of records, and to the items' subsequent chain of custody.[16] The principle of provenance (also termed the principle of "archival integrity", and a major strand in the broader principle of respect des fonds) stipulates that records originating from a common source (or fonds) should be kept together – where practicable, physically; but in all cases intellectually, in the way in which they are catalogued and arranged in finding aids. Conversely, records of different provenance should be preserved and documented separately. In archival practice, proof of provenance is provided by the operation of control systems that document the history of records kept in archives, including details of amendments made to them. The authority of an archival document or set of documents of which the provenance is uncertain (because of gaps in the recorded chain of custody) will be considered to be severely compromised.

The principles of archival provenance were developed in the 19th century by both French and Prussian archivists, and gained widespread acceptance on the basis of their formulation in the Manual for the Arrangement and Description of Archives by Dutch state archivists Samuel Muller, J. A. Feith, and R. Fruin, published in the Netherlands in 1898 (often referred to as the "Dutch Manual").[17]

Seamus Ross has argued a case for adapting established principles and theories of archival provenance to the field of modern digital preservation and curation.[18]

Provenance is also the title of the journal published by the Society of Georgia Archivists.[19]

Books

In the case of books, the study of provenance refers to the study of the ownership of individual copies of books. It is usually extended to include study of the circumstances in which individual copies of books have changed ownership, and of evidence left in books that shows how readers interacted with them.[20][21]

Provenance studies may shed light on the books themselves, providing evidence of the role particular titles have played in social, intellectual and literary history. Such studies may also add to our knowledge of particular owners of books. For instance, looking at the books owned by a writer may help to show which works influenced him or her.

Many provenance studies are historically focused, and concentrated on books owned by writers, politicians and public figures. The recent ownership of books is studied, however, as is evidence of how ordinary or anonymous readers have interacted with books.[22][23]

Provenance can be studied both by examining the books themselves (for instance looking at inscriptions, marginalia, bookplates, book rhymes, and bindings) and by reference to external sources of information such as auction catalogues.[20]

Wines

In transactions of old wine with the potential of improving with age, the issue of provenance has a large bearing on the assessment of the contents of a bottle, both in terms of quality and the risk of wine fraud. A documented history of wine cellar conditions is valuable in estimating the quality of an older vintage due to the fragile nature of wine.[24]

Recent technology developments have aided collectors in assessing the temperature and humidity history or the wine which are two key components in establishing perfect provenance. For example, there are devices available that rest inside the wood case and can be read through the wood by waving a smartphone equipped with a simple app. These devices track the conditions the case has been exposed to for the duration of the battery life, which can be as long as 15 years, and sends a graph and high/low readings to the smartphone user. This takes the trust issue out of the hands of the owner and gives it to a third party for verification.

Science

Archaeology, anthropology, and paleontology

Archaeology and anthropology researchers use provenience to refer to the exact location or find spot of an artifact, a bone or other remains, a soil sample, or a feature within an ancient site,[3] whereas provenance covers an object's complete documented history. Ideally, in modern excavations, the provenience is recorded in three dimensions on a site grid with great precision, and may also be recorded on video to provide additional proof and context. In older work, often undertaken by amateurs, only the general site or approximate area may be known, especially when an artifact was found outside a professional excavation and its specific position not recorded. The term provenience appeared in the 1880s, about a century after provenance. Outside of academic contexts, it has been used as a synonymous variant spelling of provenance, especially in American English.

Any given antiquity may have both a provenience (where it was found) and a provenance (where it has been since it was found). A summary of the distinction is that "provenience is a fixed point, while provenance can be considered an itinerary that an object follows as it moves from hand to hand."[25] Another metaphor is that provenience is an artifact's "birthplace", while provenance is its "résumé",[26] though this is imprecise (many artifacts originated as trade goods created in one region but were used and finally deposited in another).

Aside from scientific precision, a need for the distinction in these fields has been described thus:[26]

Archaeologists ... don't care who owned an object—they are more interested in the context of an object within the community of its (mostly original) users. ... [W]e are interested in why a Roman coin turned up in a shipwreck 400 years after it was made; while art historians don't really care, since they can generally figure out what mint a coin came from by the information stamped on its surface. "It's a Roman coin, what else do we need to know?" says an art historian; "The shipping trade in the Mediterranean region during late Roman times" says an archaeologist. ... [P]rovenance for an art historian is important to establish ownership, but provenience is interesting to an archaeologist to establish meaning.

In this context, the provenance can occasionally be the detailed history of where an object has been since its creation,[26] as in art history contexts – not just since its modern finding. In some cases, such as where there is an inscription on the object, or an account of it in written materials from the same era, an object of study in archaeology or cultural anthropology may have an early provenance – a known history that predates modern research – then a provenience from its modern finding, and finally a continued provenance relating to its handling and storage or display after the modern acquisition.

Evidence of provenance in the more general sense can be of importance in archaeology. Fakes are not unknown, and finds are sometimes removed from the context in which they were found without documentation, reducing their value to science. Even when apparently discovered in situ, archaeological finds are treated with caution. The provenience of a find may not be properly represented by the context in which it was found (e.g. due to stratigraphic layers being disturbed by erosion, earthquakes, or ancient reconstruction or other disturbance at a site. Artifacts can also be moved through looting as well as trade, far from their place of origin and long before modern rediscovery. Further research is often required to establish the true provenance of a find, and what the relationship is between the exact provenience and the overall provenance.

In paleontology and paleoanthropology, it is recognized that fossils can also move from their primary context and are sometimes found, apparently in-situ, in deposits to which they do not belong because they have been moved, for example, by the erosion of nearby but different outcrops. It is unclear how strictly paleontology maintains the provenience and provenance distinction. For example, a short glossary at a website (primarily aimed at young students) of the American Museum of Natural History treats the terms as synonymous,[27] while scholarly paleontology works make frequent use of provenience in the same precise sense as used in archaeology and paleoanthropology.

While exacting details of a find's provenience are primarily of use to scientific researchers, most natural history and archaeology museums also make strenuous efforts to record how the items in their collections were acquired. These records are often of use in helping to establish a chain of provenance.

Data provenance

Scientific research is generally held to be of good provenance when it is documented in detail sufficient to allow reproducibility.[28][29] Scientific workflow systems assist scientists and programmers with tracking their data through all transformations, analyses, and interpretations. Data sets are reliable when the processes used to create them are reproducible and analyzable for defects.[30] Security researchers are interested in data provenance because it can analyze suspicious data and make large opaque systems transparent.[31] Current initiatives to effectively manage, share, and reuse ecological data are indicative of the increasing importance of data provenance. Examples of these initiatives are National Science Foundation Datanet projects, DataONE and Data Conservancy, as well as the U.S. Global Change Research Program.[32] Some international academic consortia, such as the Research Data Alliance, have specific groups to tackle issues of provenance. In that case it is the Research Data Provenance Interest Group.[33]

Computer science

Within computer science, informatics uses the term "provenance"[34] to mean the lineage of data, as per data provenance, with research in the last decade extending the conceptual model of causality and relation to include processes that act on data and agents that are responsible for those processes. See, for example, the proceedings of the International Provenance Annotation Workshop (IPAW)[35] and Theory and Practice of Provenance (TaPP).[36] Semantic web standards bodies, including the World Wide Web Consortium in 2014, have ratified a standard data model for provenance representation known as PROV[37] which draws from many of the better-known provenance representation systems that preceded it, such as the Proof Markup Language and the Open Provenance Model.[38]

Interoperability is a design goal of most recent computer science provenance theories and models, for example the Open Provenance Model (OPM) 2008 generation workshop aimed at "establishing inter-operability of systems" through information exchange agreements.[39] Data models and serialisation formats for delivering provenance information typically reuse existing metadata models where possible to enable this. Both the OPM Vocabulary[40] and the PROV Ontology[41] make extensive use of metadata models such as Dublin Core and Semantic Web technologies such as the Web Ontology Language (OWL). Current practice is to rely on the W3C PROV data model, OPM's successor.[42]

There are several maintained and open-source provenance capture implementation at the operating system level such as CamFlow,[43][44] Progger[45] for Linux and MS Windows, and SPADE for Linux, MS Windows, and MacOS.[46] Operating system level provenance have gained interest in the security community notably to develop novel intrusion detection techniques.[47] Other implementations exist for specific programming and scripting languages, such as RDataTracker[48] for R, and NoWorkflow[49] for Python.

Whole-system provenance implementation for Linux

- PASS[50] – closed source – not maintained – kernel v2.6.X

- Hi-Fi[51] – open source[52] – not maintained – kernel v3.2.x

- Flogger[53] – closed source – not maintained – kernel v2.6.x

- S2Logger[54] – closed source – not maintained – kernel v2.6.x

- LPM[55] – open source[56] – not maintained – kernel v2.6.x

- Progger[57][45][58][59] – open source[60] – not maintained – kernel v2.6.x and kernel v.4.14.x

- CamFlow[61][62][63] – open source[64] – maintained – kernel v5.9.X

Petrology

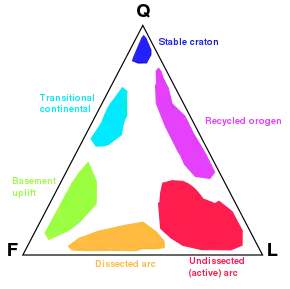

In the geologic use of the term, provenance instead refers to the origin or source area of particles within a rock, most commonly in sedimentary rocks. It does not refer to the circumstances of the collection of the rock. The provenance of sandstone, in particular, can be evaluated by determining the proportion of quartz, feldspar, and lithic fragments (see diagram).

Seed provenance

Seed provenance refers to the specified area in which plants that produced seed are located or were derived. Local provenancing is a position maintained by ecologists that suggests that only seeds of local provenance should be planted in a particular area. However, this view depends on the adaptationist program – a view that populations are universally locally adapted.[65] It is maintained that local seed is best adapted to local conditions, and that outbreeding depression will be avoided. Evolutionary biologists suggest that strict adherence to provenance collecting is not a wise decision because:

- Local adaptation is not as common as assumed.[66]

- Background population maladaptation can be driven by natural processes.[66]

- Human actions of habitat fragmentation drive maladaptation up and adaptive potential down.[67]

- Natural selection is changing rapidly due to climate change.[68] and habitat fragmentation

- Population fragments are unlikely to divergence by natural selection since fragmentation (< 500 years). This leads to a low risk of outbreeding depression.[69]

Provenance trials, where material of different provenances are planted in a single place or at different locations spanning a range of environmental conditions, is a way to reveal genetic variation among provenances. It also contributes to an understanding of how different provenances respond to various climatic and environmental conditions and can as such contribute with knowledge on how to strategically select provenances for climate change adaptation.[70]

Computers and law

The term provenance is used when ascertaining the source of goods such as computer hardware to assess if they are genuine or counterfeit. Chain of custody is an equivalent term used in law, especially for evidence in criminal or commercial cases.

Software provenance encompasses the origin of software and its licensing terms. For example, when incorporating a free, open source or proprietary software component in an application, one may wish to understand its provenance to ensure that licensing requirements are fulfilled and that other software characteristics can be understood.

Data provenance covers the provenance of computerized data. There are two main aspects of data provenance: ownership of the data and data usage. Ownership will tell the user who is responsible for the source of the data, ideally including information on the originator of the data. Data usage gives details regarding how the data has been used and modified and often includes information on how to cite the data source or sources. Data provenance is of particular concern with electronic data, as data sets are often modified and copied without proper citation or acknowledgement of the originating data set. Databases make it easy to select specific information from data sets and merge this data with other data sources without any documentation of how the data was obtained or how it was modified from the original data set or sets.[32] The automated analysis of data provenance graphs has been described as a mean to verify compliance with regulations regarding data usage such as introduced by the EU GDPR.[71]

Secure Provenance refers to providing integrity and confidentiality guarantees to provenance information. In other words, secure provenance means to ensure that history cannot be rewritten, and users can specify who else can look into their actions on the object.[72][73]

A simple method of ensuring data provenance in computing is to mark a file as read only. This allows the user to view the contents of the file, but not edit or otherwise modify it. Read only can also in some cases prevent the user from accidentally or intentionally deleting the file.

References

- OED: "The fact of coming from some particular source or quarter; source, derivation"

- "Better Safe Than Sorry: American Museums Take Measures Mindful of Repatriation of African Art", by Robin Scher, Art News, 11 June 2019

- "Selected Archeological Terms". 10 February 2013. Archived from the original on 10 February 2013.

- "Spoliation of Works of Art during the Holocaust and World War II period". www.nationalmuseums.org.uk. National Museum Directors' Council Website. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- "A 20th Century Master Scam". Archived from the original on 2012-02-25. Retrieved 2012-03-06.

- Reynolds, Lisa, An Art Provenance Research Guide available at University of North Carolina Master's Papers Archived 2012-07-07 at Archive.today

- "Cartellino". Glossary. London: The National Gallery. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- "Course Reserves - nal-vam.on.worldcat.org". nal-vam.on.worldcat.org.

- "The Art World in Britain 1660–1735". Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- "What's covered in the Indexes (Getty Research Institute)". www.getty.edu.

- "Frick Art Reference Library". www.frick.org. The Frick Collection. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- "Netherlands Institute for Art History Databases". Archived from the original on 2012-09-16. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- Dynasties, a catalogue of an exhibition at the Tate Gallery, Karen Hearn, page 158

- Grosvenor, Bendor. "Art History News". www.arthistorynews.com.

- Abukhanfusa, Kerstin; Sydbeck, Jan, eds. (1994). The Principle of Provenance: report from the First Stockholm Conference on Archival Theory and the Principle of Provenance, 2–3 September 1993. Stockholm: Swedish National Archives. ISBN 9789188366115.

- Douglas, Jennifer (2010). "Origins: evolving ideas about the principle of provenance". In Eastwood, Terry; MacNeil, Heather (eds.). Currents of Archival Thinking. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Libraries Unlimited. pp. 23–43 (27–28). ISBN 9781591586562.

- Ross, Seamus (2012). "Digital Preservation, Archival Science and Methodological Foundations for Digital Libraries". New Review of Information Networking. 17 (1): 43–68 (esp. 50–53). doi:10.1080/13614576.2012.679446. S2CID 58540553.

- "Provenance, Journal of the Society of Georgia Archivists".

- Pearson, David (1998). Provenance Research in Book History: a Handbook. British Library. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-7123-4598-9.

- Pearson, David (2005). "Provenance and Rare Book Cataloguing: Its Importance and Its Challenges". In Shaw, David J. (ed.). Books and Their Owners: Provenance Information and The European Cultural Heritage. Consortium of European Research Libraries. pp. 1–9. ISBN 978-0-9541535-3-3.

- Curwen, Tony & Jonsson, Gunilla (2007). "Provenance and the Itinerary of the Book: Recording Provenance Data in On-line Catalogues". In Shaw, David J. (ed.). Imprints and Owners: Recording the Cultural Geography of Europe. Consortium of European Research Libraries. pp. 31–47. ISBN 978-0-9541535-6-4.

- Jackson, H. J. (2001). Marginalia: Readers Writing in Books. Yale University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-300-08816-8.

- winepros.com.au. Oxford Companion to Wine. "ageing". Archived from the original on 2008-07-26. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- Joyce, Rosemary A. (2012). "From Place to Place: Provenience, Provenance, and Archaeology". In Feigenbaum, Gail; Jackson Reist, Inge (eds.). Provenance: An Alternate History of Art. Issues & Debates. Getty Research Institute. p. 48. ISBN 978-1606061220.

- Hirst, K. Kris (December 22, 2016). "Provenience, Provenance, Let's Call the Whole Thing Off: What is the difference in meaning between provenience and provenance?". ThoughtCo. Dotdash/IAC. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- "Glossary". PaleoPortal Collections Management. American Museum of Natural History. 2009. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- Altintas, I.; Berkley, C.; Jaeger, E.; Jones, M.; Ludascher, B.; Mock S. (2004) "Kepler: An extensible system for design and execution of scientific workflows". Proceedings of 16th International Conference on Scientific and Statistical Database Management, pp. 423–424

- Pasquier, Thomas; Lau, Matthew K.; Trisovic, Ana; Boose, Emery R.; Couturier, Ben; Crosas, Mercè; Ellison, Aaron M.; Gibson, Valerie; Jones, Chris R.; Seltzer, Margo (5 September 2017). "If these data could talk". Scientific Data. 4: 170114. Bibcode:2017NatSD...470114P. doi:10.1038/sdata.2017.114. PMC 5584398. PMID 28872630.

- Boose, E.; Ellison, A.; Osterweil, L.; Clarke, L.; Podorozhny, R., Hadley, J.; Wise, A.; Foster, D. (2007) Ensuring reliable datasets for environmental models and forecasts. Ecological Informatics, 2(3):237–247

- Bates, Adam; Hassan, Wajih Ul (2019). "Can Data Provenance Put an End to the Data Breach?". IEEE Security & Privacy. 17 (4): 88–93. doi:10.1109/MSEC.2019.2913693. S2CID 195832747.

- Ma, X.; Fox, P.; Tilmes, C.; Jacobs, K.; Waple, A. (2014) Capturing and presenting provenance of global change information. Nature Climate Change 4 (6), 409-413.

- "Research Data Provenance IG". RDA. 11 September 2013.

- Tan, Yu Shyang; Ko, Ryan K.L.; Holmes, Geoff (November 2013). "Security and Data Accountability in Distributed Systems: A Provenance Survey". 2013 IEEE 10th International Conference on High Performance Computing and Communications & 2013 IEEE International Conference on Embedded and Ubiquitous Computing. IEEE: 1571–1578. doi:10.1109/hpcc.and.euc.2013.221. ISBN 9780769550886. S2CID 16890856.

- "International Provenance and Annotation Workshop". International Provenance and Annotation Workshop. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- "TaPP 2015". workshops.inf.ed.ac.uk. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- "PROV-Overview". www.w3.org.

- "Provenance Web Services". openprovenance.org.

- Moreau et al. (2008) The Open Provenance Model: An Overview, in J. Freire, D. Koop, and L. Moreau (Eds.): IPAW 2008, LNCS 5272, pp. 323–326, 2008. Springer.

- Zhao, J. (2010) "Open Provenance Model Vocabulary Specification", accessed 2016-04-09.

- Lebo et al. (eds.) "PROV-O: The PROV Ontology", accessed 2016-04-09.

- Belhajjame, Khalid (4 April 2013). "W3C PROV Implementations: Preliminary Analysis". Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- CamFlow, a Linux security module by the University of Cambridge and Harvard University

- Pasquier, Thomas; Han, Xueyuan; Goldstein, Mark; Moyer, Thomas; Eyers, David; Seltzer, Margo; Bacon, Jean (2017). "Practical Whole-system Provenance Capture". Proceedings of the 2017 Symposium on Cloud Computing. ACM: 405–418. arXiv:1711.05296. Bibcode:2017arXiv171105296P. doi:10.1145/3127479.3129249. ISBN 9781450350280. S2CID 4885447.

- Li, Xin; Joshi, Chaitanya; Tan, Alan Yu Shyang; Ko, Ryan Kok Leong (August 2015). "Inferring User Actions from Provenance Logs". 2015 IEEE Trustcom/BigDataSE/ISPA. IEEE. 1: 742–749. doi:10.1109/trustcom.2015.442. hdl:10289/9505. ISBN 9781467379526. S2CID 1904317.

- Gehani, Ashish (8 February 2019). "SPADE: Support for Provenance Auditing in Distributed Environments". Retrieved 10 February 2019 – via GitHub.

- Han, Xueyuan; Pasquier, Thomas; Bates, Adam; Mickens, James; Seltzer, Margo (2020-02-26). "Unicorn: Runtime Provenance-Based Detector for Advanced Persistent Threats". Network and Distributed System Security Symposium. doi:10.14722/ndss.2020.24046. ISBN 978-1-891562-61-7.

- "An R library to collect provenance from R scripts.: End-to-end-provenance/RDataTracker". 12 December 2018 – via GitHub.

- "Supporting infrastructure to run scientific experiments without a scientific workflow management system.: gems-uff/noworkflow". 19 December 2018 – via GitHub.

- Muniswamy-Reddy, Kiran-Kumar; Holland, David; Seltzer, Margo (2006). "Provenance-Aware Storage Systems". USENIX 2006 Annual Technical Conference Refereed Paper.

- Pohly, Devin J.; McLaughlin, Stephen; McDaniel, Patrick; Butler, Kevin (2012). "Hi-Fi: Collecting High-fidelity Whole-system Provenance". Proceedings of the 28th Annual Computer Security Applications Conference. ACM: 259–268. doi:10.1145/2420950.2420989. ISBN 9781450313124. S2CID 5622944.

- Pohly, Devin J. (19 August 2013). "Hi-Fi".

- Ko, Ryan K. L.; Jagadpramana, Peter; Lee, Bu Sung (November 2011). "Flogger: A File-Centric Logger for Monitoring File Access and Transfers within Cloud Computing Environments". 2011IEEE 10th International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications. IEEE: 765–771. doi:10.1109/trustcom.2011.100. ISBN 9781457721359. S2CID 15858535.

- Suen, Chun Hui; Ko, Ryan K.L.; Tan, Yu Shyang; Jagadpramana, Peter; Lee, Bu Sung (July 2013). "S2Logger: End-to-End Data Tracking Mechanism for Cloud Data Provenance". 2013 12th IEEE International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications. IEEE: 594–602. doi:10.1109/trustcom.2013.73. ISBN 9780769550220. S2CID 504801.

- Bates, Adam; Tian, Dave; Butler, Kevin R. B.; Moyer, Thomas (2015). "Trustworthy Whole-system Provenance for the Linux Kernel". Proceedings of the 24th USENIX Conference on Security Symposium. USENIX Association: 319–334.

- "uf_sensei / redhat-linux-provenance-release – Bitbucket". bitbucket.org.

- Ko, Ryan K.L.; Will, Mark A. (June 2014). "Progger: An Efficient, Tamper-Evident Kernel-Space Logger for Cloud Data Provenance Tracking". 2014 IEEE 7th International Conference on Cloud Computing. IEEE: 881–889. doi:10.1109/cloud.2014.121. hdl:10289/9018. ISBN 9781479950638. S2CID 17536574.

- Taha, Mohammad M. Bany; Chaisiri, Sivadon; Ko, Ryan K. L. (August 2015). "Trusted Tamper-Evident Data Provenance". 2015 IEEE Trustcom/BigDataSE/ISPA. IEEE: 646–653. doi:10.1109/trustcom.2015.430. ISBN 9781467379526. S2CID 10720318.

- Garae, Jeffery; Ko, Ryan K.L.; Chaisiri, Sivadon (August 2016). "UVisP: User-centric Visualization of Data Provenance with Gestalt Principles". 2016 IEEE Trustcom/BigDataSE/ISPA. IEEE: 1923–1930. doi:10.1109/trustcom.2016.0294. hdl:10289/10996. ISBN 9781509032051. S2CID 11231512.

- "CROWLaboratory/Progger". GitHub. Retrieved 2018-08-04.

- Pasquier, Thomas; Singh, Jatinder; Eyers, David; Bacon, Jean (2015). "Camflow: Managed Data-Sharing for Cloud Services". IEEE Transactions on Cloud Computing. 5 (3): 472–484. arXiv:1506.04391. Bibcode:2015arXiv150604391P. doi:10.1109/TCC.2015.2489211. S2CID 11537746.

- Pasquier, Thomas; Han, Xueyuan; Goldstein, Mark; Moyer, Thomas; Eyers, David; Seltzer, Margo; Bacon, Jean (2017). "Practical Whole-system Provenance Capture". Proceedings of the 2017 Symposium on Cloud Computing. ACM: 405–418. arXiv:1711.05296. Bibcode:2017arXiv171105296P. doi:10.1145/3127479.3129249. ISBN 9781450350280. S2CID 4885447.

- Pasquier, Thomas; Han, Xueyuan; Moyer, Thomas; Bates, Adam; Hermant, Olivier; Eyers, David; Bacon, Jean; Seltzer, Margo (14 October 2018). "Runtime Analysis of Whole-System Provenance". 25th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security. arXiv:1808.06049. Bibcode:2018arXiv180806049P.

- "CamFlow: Practical Linux Provenance". camflow.org.

- Gould S. J.; Lewontin; R. C. (1979). "The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm: A Critique of the Adaptationist Programme". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B: Biological Sciences, 205: 581-598

- Gould & Lewontin 1979

- Willi Y, Van Buskirk J, Hoffmann AA (2006) Limits to the adaptive potential of small populations. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 37: 433-458.

- Parmesan C (2006) Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 37: 637-669.

- Frankham R, Ballou J, Eldridge M, Lacy R, Ralls K, et al. (2011) Predicting the probability of outbreeding depression. Conservation Biology.

- Konnert, M., Fady, B., Gömöry, D., A’Hara, S., Wolter, F., Ducci, F. Koskela, J., Bozzano, M., Maaten, T. and Kowalczyk, J. (2015). "Use and transfer of forest reproductive material in Europe in the context of climate change" (PDF). European Forest Genetic Resources Programme (EUFORGEN), Bioversity International, Rome, Italy: xvi and 75 p.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Pasquier, Thomas; Singh, Jatinder; Powles, Julia; Eyers, David; Seltzer, Margo; Bacon, Jean (1 April 2018). "Data provenance to audit compliance with privacy policy in the Internet of Things". Personal and Ubiquitous Computing. 22 (2): 333–344. doi:10.1007/s00779-017-1067-4. ISSN 1617-4909. S2CID 4594884.

- The Case of the Fake Picasso: Preventing History Forgery with Secure Provenance, Hasan et al., USENIX FAST 2009.

- Xinlei (Oscar) Wang, Kai Zeng, Kannan Govindan and Prasant Mohapatra. (2012). "Chaining for securing data provenance in distributed information networks". In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference for Military Communications. MILCOM '12. doi:10.1109/MILCOM.2012.6415609.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Bibliography

Provenance in book studies

- Adams, Frederick B (1969). The Uses of Provenance. Berkeley: University of California.

- Myers, Robin; Harris, Michael; Mandelbrote, Giles, eds. (2007). Books on the move: tracking copies through collections and the book trade. London: British Library. ISBN 978-0-7123-0986-8.

- Pearson, David (2019). Provenance Research in Book History: a Handbook. London: Bodleian Library. ISBN 978-0-7123-4598-9.

- Shaw, David J., ed. (2005). Books and Their Owners: Provenance Information and the European Cultural Heritage. London: Consortium of European Research Libraries. ISBN 978-0-9541535-3-3.

- Shaw, David J., ed. (2007). Imprints and Owners: Recording the Cultural Geography of Europe. London: Consortium of European Research Libraries. ISBN 978-0-9541535-6-4.

External links

| Look up provenance in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- The National Gallery of Art Washington gives brief provenances for most featured works

- EU Provenance Project - a technology project that sought to support the electronic certification of data provenance

- W3C Provenance Working Group

- W3C Provenance Outreach Information