Burghley House

Burghley House (/ˈbɜːrli/[1]) is a grand sixteenth-century English country house near Stamford, Lincolnshire. It is a leading example of the Elizabethan prodigy house, built and still lived in by the Cecil family. The exterior largely retains its Elizabethan appearance, but most of the interiors date from remodellings before 1800. The house is open to the public on a seasonal basis[2] and displays a circuit of grand and richly furnished state apartments. Its park was laid out by Capability Brown.[3]

| Burghley House | |

|---|---|

The façade of Burghley House | |

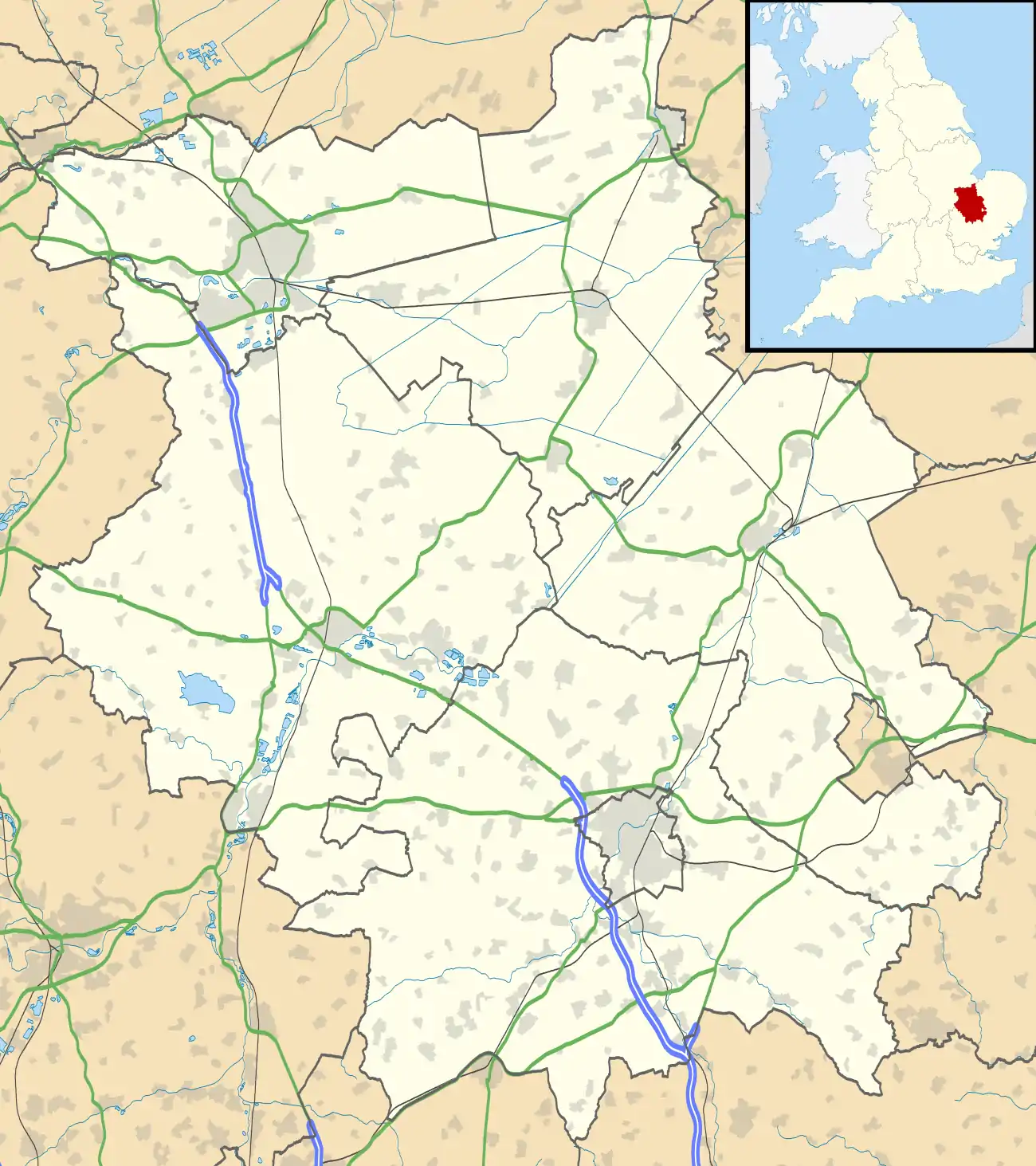

Location within Cambridgeshire | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Elizabethan |

| Town or city | Peterborough |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 52.642393°N 0.452585°W |

| Construction started | 1555 |

| Completed | 1587 |

| Cost | c. £21,000 (1587) |

| Client | William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley |

| Technical details | |

| Structural system | Ashlar limestone |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley |

| Website | |

| www.burghley.co.uk | |

The house is on the boundary of the civil parishes of Barnack and St Martin's Without in the Peterborough unitary authority of Cambridgeshire. It was formerly part of the Soke of Peterborough, an historic area that was traditionally associated with Northamptonshire. It lies 0.9 miles (1.4 km) south of Stamford and 10 miles (16 km) northwest of Peterborough city centre.

The house is now run by the Burghley House Preservation Trust, which is controlled by the Cecil family.

History

Burghley was built for Sir William Cecil, later 1st Baron Burghley, who was Lord High Treasurer to Queen Elizabeth I of England, between 1555 and 1587, and modelled on the privy lodgings of Richmond Palace.[4][5][6] It was subsequently the residence of his descendants, the Earls, and since 1801, the Marquesses of Exeter. Since 1961, it has been owned by a charitable trust established by the family.[6][7]

Lady Victoria Leatham, antiques expert and television personality, followed her father, Olympic gold-medal winning athlete, IAAF President and MP, David Cecil, the 6th Marquess, by running the house from 1982 to 2007. The Olympic corridor commemorates her father.[8] Her daughter, Miranda Rock, is now the most active live-in trustee.[7][9] However, the Marquessate passed it in 1988 to Victoria's uncle, Martin Cecil, 7th Marquess of Exeter, and then to his son, William Michael Anthony Cecil, both Canadian ranchers on land originally bought by the 5th Marquess, who have not lived at Burghley.[10]

The house is one of the main examples of stonemasonry and proportion in sixteenth-century English Elizabethan architecture, reflecting the prominence of its founder, and the lucrative wool trade of the Cecil estates. It has a suite of rooms remodelled in the baroque style, with carvings by Grinling Gibbons.[4] The main part of the house has 35 major rooms, on the ground and first floors. There are more than 80 lesser rooms and numerous halls, corridors, bathrooms, and service areas.[6][11][12][13]

In the seventeenth century, the open loggias around the ground floor were enclosed. Although the house was built in the floor plan shape of the Letter E, in honour of Queen Elizabeth, it is now missing its north-west wing. During the period of the 9th Earl's ownership, and under the guidance of the famous landscape architect, Capability Brown, the south front was raised to alter the roof line, and the north-west wing was demolished to allow better views of the new parkland.[4][6][11][13] A chimney-piece after the design of Venetian printmaker Giovanni Battista Piranesi was also added during his tenure.[14]

The so-called "Hell Staircase" and its neighbour "The Heaven Room" has substantial ceiling paintings by Antonio Verrio, between 1697 and 1699. The walls to the "Hell Staircase" are by Thomas Stothard, who completed the work about a century later. The Bow Room is decorated with wall and ceiling paintings by Louis Laguerre.

Art collection

Although depleted of a number of important pieces by death duties in the 1960s, the Burghley art collections are otherwise mainly intact and are very extensive. The house still displays several hundred paintings, a large proportion of which are of the 17th century, bought in Italy by John Cecil, 5th Earl of Exeter (c. 1648–1700), and by Brownlow Cecil, the 9th Earl (1725–1793). They visited Italy eight times, bringing back large quantities of art. John Cecil purchased 300 works of art during his 22 years in Burghley and spent on his last visit to Europe £5,000 (c. £535,000 in 2017 currency[15]).

The Chapel has a large altarpiece by Paolo Veronese and his workshop, and two large paintings by Johann Carl Loth, a German painter active in Venice with few works in British collections. There are in total seven works by Luca Giordano, including a self-portrait.[16]

In the Pagoda Room, there are portraits of the Cecil family, Elizabeth I, Henry VIII, and Oliver Cromwell. Many delicately painted walls and ceilings of the house were done by Antonio Verrio.[17] The Billiard Room displays six oval portraits of members of the Order of Little Bedlam, the 5th Earl’s drinking club.[18]

There are a number of outstanding pieces of furniture including work by celebrated 18th-century cabinet makers, Ince and Mayhew, in addition to silver, tapestry and collections of porcelain, much of this is on public display in the state rooms.

A new "Treasury" space in the Brewhouse displays annually changing exhibitions highlighting aspects of the collections.

Parkland

The avenues in the park were all laid out according to the 1755-1779 designs by Capability Brown,[19] paying due respect to pre-existing plantings, some of which were from the 16th century or earlier.[20][21]

Brown also created the park's man-made lake in 1775-80. He discovered a seam of waterproof "blue" clay in the grounds, and was able to enlarge the original nine-acre (36,000 m²) pond to the existing 26-acre (105,000 m²) lake. Its design gives the impression of a meandering river. Brown designed the Lion Bridge at a cost of 1,000 guineas (£1,050[nb 1][22]) in 1778. He was paid £23,000 in total of the park designs in Burghley. Brown's landscape has been conserved by planting 30,000 new trees between 2012 and 2016.

Originally, Coade-stone lions were used as ornamentation. After these weathered, the existing stone examples were made by local mason Herbert Gilbert in 1844. Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert planted two trees to commemorate their visit.[23]

As well as the annual Burghley Horse Trials,[24] the park plays host to the "Burghley Run" for Stamford School and an annual meet for the Cambridge University Draghounds.[25]

Recent developments have included starting a sculpture garden around the old ice house and, in 2007, a "garden of surprises" was created using traditional ideas of water traps, shell grottos and a mirror maze, but in a 21st-century style.[26] The Burghley House trust has commissioned contemporary artwork in the grounds from leading artists.[27]

The parkland and gardens of Burghley House are listed Grade II* on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.[28]

Today

The Lincolnshire county boundary crosses the park between the town of Stamford and the house. Burghley is located in the ancient Soke of Peterborough, once a part of Northamptonshire but now for ceremonial purposes in Cambridgeshire; for planning and other municipal functions the house is in the Peterborough unitary authority.[29]

The house is a Grade I listed building, with separately Grade I listed north courtyard and gate. The listing document for the House provided this summary: "C19 and C20 formal gardens and pleasure grounds, developed from those originally designed by Lancelot Brown, surrounded by a park of C16 origins for which Brown provided extensive plans between 1754 and 1777". [30][31]

The residents of the house since 2007 were Miranda Rock, director of the Burghley House Preservation Trust, granddaughter of the 6th Marquess of Exeter and daughter of Lady Victoria, Leathamn[32] with Orlando Rock (chairman of Christie’s UK) and their family. Data before the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom indicated that the number of visitors to the site each year had almost doubled during Miranda Rock's tenure, to 110,000.[33] As of early July 2020, only the gardens had reopened to visitors, with advance booking; because social distancing would not be practical indoors, the House was not expected to reopen until March 2021.[34]

Filming

Burghley House has been featured in several films. Its virtually unaltered Elizabethan façades and a variety of historic interiors make it an ideal location for historical and period movies.

Films and television programmes made at Burghley include:

- Treasure Houses of Britain – 1985 television documentary that shows the house and interviews Victoria Leatham

- Middlemarch

- The Da Vinci Code

- Pride & Prejudice[35]

- Elizabeth: The Golden Age

- BBC Two filmed a 15-part series about Burghley broadcast in the Castle in the Country programmes 2006.

- Featured in the 2007 BBC series How We Built Britain

- Burghley House was one of fifteen structures featured in the 2010 BBC series Climbing Great Buildings

- In 2011 Burghley House featured on the TV programme Royal Upstairs Downstairs.

- Housefull 2: The Dirty Dozen Indian Movie 2012

- Antiques Roadshow, Season 20, Episode 18[36]

- The Crown - filmed in season 4 of the Netflix series to depict Windsor Castle[37]

- Top Gear – Series 25, Episode 6

Lost village

The medieval settlement of Burghley, mentioned in Domesday, was abandoned by 1450. Failure to locate its site leads to the supposition that the settlement was near Burghley House, and perhaps lies below the estate.[38][39]

See also

- Burghley Nef, a silver-gilt salt cellar now in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum

- Cecil House, 16th- and 17th-century demolished London residences

- Theobalds House, second house half-way to London, built by the founder in Hertfordshire

Notes

- Brown's works costs equate to between £135000 (auto-generated on minimum basis) or £138,000 (2011) (Bank of England calculator).

References

- "Burghley or Burleigh". Collins Dictionary. n.d. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- Covid-19 outbreak

- Turner, Roger (1999). Capability Brown and the Eighteenth Century English Landscape (2nd ed.). Chichester: Phillimore. pp. 110–112.

- Historic England. "Burghley House (347962)". PastScape. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- Alford, Stephen (2008). Burghley: William Cecil at the Court of Elizabeth I.

- Leatham, Lady Victoria (1992). Burghley:The life of a great house. Herbert Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1-871569-47-6.

- "Charity commission summary for charity 258489 Burghley House Preservation Trust Limited".

- "Great Houses". Daily Telegraph.

- "Burghley House Preservation Trust Limited". Archived from the original on 24 August 2010. at Burghley's web site

- "Martin Cecil mural fills missing piece of 100 Mile House history". BC Local News. 21 September 2011. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- Pevsner, Nicholas. The Buildings of England. Northamptonshire.

- Leaflet published by the Trust

- Leatham, Lady Victoria (2000). Great Houses of Britain. Burghley House (3 ed.). Heritage House Group Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85101-351-0.

- Lowe, Adam. "Messing About With Masterpieces: New Work by Giambattista Piranesi (1720-1778)," Art in Print Vol. 1 No. 1 (May-June 2011), p.17

- Archives, The National. "The National Archives - Currency converter: 1270–2017". Currency converter. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- Burghley collections, search on Luca Giordano

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1127501)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- Historic England. "The park, describing stages of remodelling (868212)". PastScape. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- Historic England. "Original park (348156)". PastScape. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- "The Deer Park". Burghley. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- Bank of England Inflation Calculator, see below Archived 5 February 2014 at WebCite

- "South Gardens". Burghley Trust. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- "Burghley Horse trials".

- "Cambridge University Draghounds meeting calendar, showing run at Burghley". Archived from the original on 12 March 2010.

- "Burghley's web page for the Garden of Surprises". Archived from the original on 23 August 2010.

- "Fresh Take". Burghley Trust. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- Historic England, "Burghley House (garden) (1000359)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 11 January 2017

- Historic England. "Burghley House (1000359)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1331234)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- NORTH FORECOURT AREA RAILINGS AND GATES AT BURGHLEY HOUSE

- The Guardians of Burghley House

- Burghley House: The 500-year story of one of the very greatest houses in Britain

- COVID-19 (Coronavirus) Update

- "Pride and Prejudice". The Castles and Manor Houses of Cinema's Greatest Period Films. Architectural Digest. January 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- "Burghley House". TV.com. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- "The Crown returns with Burghley House as Windsor Castle". The Lincolnite.

- Historic England. "The deserted medieval village of Burghley (348033)". PastScape. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- 25 of Britain’s best stately homes

- Lewis, Samuel, ed. (1848). A Topographical Dictionary of England. pp. 266–269, 'Marston-Maisey – Martin-Hussingtree'. Retrieved 1 January 2011. description of the St Martin's parish, with mention the visits of Queens Elisabeth & Victoria to Burghley House

Further reading

- Gifford, Gerald (2002). A Descriptive Catalogue of the Music Collection at Burghley House, Stamford. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-0460-0.

- Raffaele De Giorgi, "Couleur, couleur!". Antonio Verrio: un pittore in Europa tra Seicento e Settecento (Edifir, Firenze 2009). ISBN 9788879704496

Video clips

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Burghley House. |

- Official website

- Burghley House entry from The DiCamillo Companion to British & Irish Country Houses

- Eventful.com: Burghley House page

- Horse trials summarised

- Panoramic view of house and grounds

- Images of England entry for Burghley House

- Photos of Burghley House and parklands on geograph

- Review of Gardens of Surprise