Castle Howard

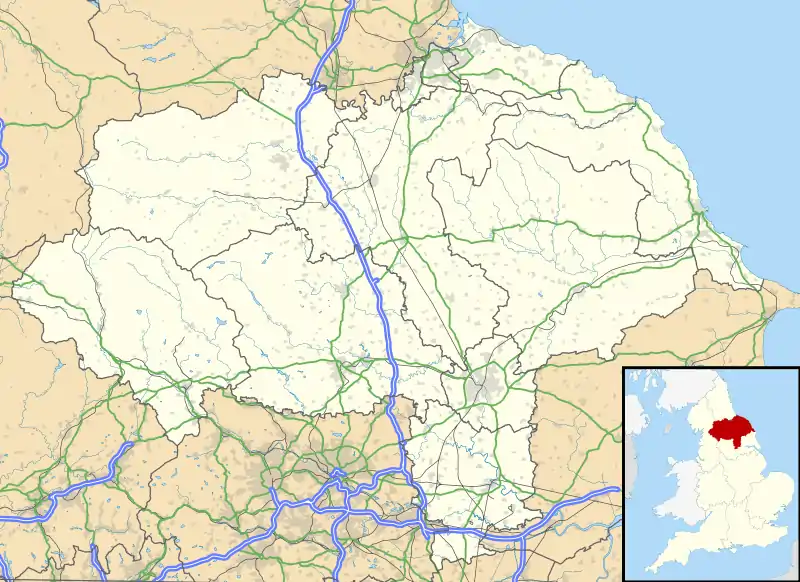

Castle Howard is a stately home in North Yorkshire, England, within the civil parish of Henderskelfe, located 15 miles (24 km) north of York. It is a private residence and has been the home of the Carlisle branch of the Howard family for more than 300 years. Castle Howard is not a fortified structure, but the term "castle" is sometimes used in the name of an English country house that was built on the site of a former castle.

| Castle Howard | |

|---|---|

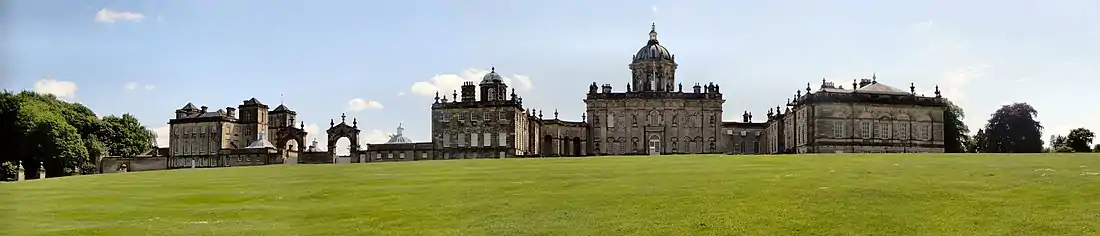

South (garden) face of Castle Howard | |

| Type | Stately home |

| Location | York, England |

| Coordinates | 54°7′17″N 0°54′21″W |

| OS grid reference | SE 71635 70088 |

| Built | 1701–1811 |

| Architect | John Vanbrugh |

| Architectural style(s) | English Baroque |

| Owner | Castle Howard Estate Limited[1] |

| Website | castlehoward.co.uk |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Castle Howard and East Court |

| Designated | 25 January 1954 |

| Reference no. | 1316030 |

| Official name | Castle Howard |

| Designated | 10 May 1984 |

| Reference no. | 1001059 |

Location of Castle Howard in North Yorkshire | |

The house is familiar to television and film audiences as the fictional "Brideshead", both in Granada Television's 1981 adaptation of Evelyn Waugh's Brideshead Revisited and in a two-hour 2008 remake for cinema. Today, it is part of the Treasure Houses of England group of heritage houses.

History

The creation of Castle Howard began in 1699 with the destruction of the small village Henderskelfe and with the start of design work by John Vanbrugh for the 3rd Earl of Carlisle.[2] Construction began in 1701, and it took over 100 years to complete. The site was that of the ruined Henderskelfe Castle, which had come into the Howard family after the marriage of the 4th Duke of Norfolk to Elizabeth Leyburne, widow of the 4th Baron Dacre. In 1577, the 4th Duke of Norfolk's third son, Lord William Howard, had married his step-sister Elizabeth Dacre, youngest daughter of the 4th Baron Dacre. She brought with her the sizable estates of Henderskelfe and Naworth Castle. The 3rd Earl of Carlisle was a male-line descendant of Lord William Howard.

The house is surrounded by a large estate which, at the time of the 7th Earl of Carlisle, covered over 13,000 acres (5,300 ha) and included the villages of Welburn, Bulmer, Slingsby, Terrington and Coneysthorpe.[3] The estate was served by its own railway station, Castle Howard station, from 1845 to the 1950s.[4]

After the death of the 9th Earl of Carlisle in 1911, Castle Howard was inherited by his fifth son, Geoffrey Howard, with later earls having Naworth Castle as their northern country house. In 1952, Castle Howard was opened to the public by its then owner, Lord Howard of Henderskelfe, a younger son of Geoffrey Howard. It is now owned by a Howard family company, Castle Howard Estate Limited,[1] and managed by the Hon. Nicholas Howard (the second son of Lord Howard of Henderskelfe) and his wife, Victoria.

In 2003, the grounds were excavated over three days by Channel 4's Time Team, searching for evidence of a local village lost to allow for the landscaping of the estate.

House

The 3rd Earl of Carlisle first spoke to William Talman, a leading architect, but commissioned Vanbrugh, a fellow member of the Kit-Cat Club, to design the building. Castle Howard was that gentleman-dilettante's first foray into architecture, but he was assisted by Nicholas Hawksmoor.

Vanbrugh's design evolved into a Baroque structure with two symmetrical wings projecting to either side of a north-south axis. The crowning central dome was added to the design at a late stage, after building had begun. Construction began at the east end, with the East Wing constructed from 1701–03, the east end of the Garden Front from 1701–06, the Central Block (including dome) from 1703–06, and the west end of the Garden Front from 1707–09. All are exuberantly decorated in Baroque style, with coronets, cherubs, urns and cyphers, with Roman Doric pilasters on the north front and Corinthian on the south. Many interiors were decorated by Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini.

_-_north_west_view.JPG.webp)

The Earl then turned his energies to the surrounding garden and grounds. Although the complete design is shown in the third volume of Colen Campbell's Vitruvius Britannicus, published in 1725, the West Wing was not yet started when Vanbrugh died in 1726, despite his remonstration with the Earl. The house remained incomplete on the death of the 3rd Earl in 1738, but the remaining construction finally started at the direction of the 4th Earl. However, Vanbrugh's design was not completed: the West Wing was built in a contrasting Palladian style to a design by the 3rd Earl's son-in-law, Sir Thomas Robinson. The new wing remained incomplete, with no first floor or roof, at the death of the 4th Earl in 1758; although a roof had been added, the interior remained undecorated by the death of Robinson in 1777. Rooms were completed stage by stage over the following decades, but the whole was not completed until 1811 under Charles Heathcote Tatham.

A large part of the house was destroyed by a fire which broke out on 9 November 1940.[5] The dome, the central hall, the dining room and the state rooms on the east side were entirely destroyed. Antonio Pellegrini's ceiling decoration, the Fall of Phaeton, was lost when the dome collapsed. In total, twenty pictures (including two Tintorettos) and several valuable mirrors were lost. The fire took the Malton and York Fire Brigades eight hours to bring under control.

Some of the devastated rooms have been restored over the following decades. In 1960–61 the dome was rebuilt, and in the following couple of years Pellegrini's Fall of Phaeton was recreated on the underside of the dome.

Some first floor rooms were superficially restored for the 2008 filming, and now house an exhibition. The South East Wing remains a shell, although it has been restored externally. Castle Howard is one of the largest country houses in England, with a total of 145 rooms.

According to figures released by the Association of Leading Visitor Attractions, over 269,000 people visited Castle Howard in 2019.[6]

In 2009 an underwater ground-source heat recovery system was installed under the castle's lake that halved the heating bill.[7]

Gardens

Castle Howard has extensive and diverse gardens.[8] There is a large formal garden immediately behind the house. The house is prominently situated on a ridge and this was exploited to create an English landscape park, which opens out from the formal garden and merges with the park. The gardens are Grade I listed on the National Register of Historic Parks and Gardens. [9]

Two major garden buildings are set into this landscape: the Temple of the Four Winds at the end of the garden, and the Mausoleum in the park. There is also a lake on either side of the house. There is a woodland garden, Ray Wood, and the walled garden contains decorative rose and flower gardens. Further buildings outside the preserved gardens include Hawksmoor's Pyramid, restored in 2015, an obelisk, and several follies and eyecatchers in the form of fortifications which have been restored in recent years. In nearby Pretty Wood there are two more monuments, The Four Faces and a smaller pyramid by Hawksmoor. The grounds of Castle Howard are also used as part of at least two charity running races during the year. Additionally a free, weekly, 5 km parkrun takes place every Saturday morning at 9 am in the gardens. This is jointly hosted by the local community and members of staff at Castle Howard.

Located on the estate, but operating separately from the house and gardens and run by an entirely independent charitable trust, is the 127 acres (51 ha) Yorkshire Arboretum.[10] Originally created through the enthusiasm and partnership of George Howard (Lord Howard of Henderskelfe) and James Russell, over a period of eighteen years, from 1975 to 1992, it was opened to the public for the first time in 1999 and a new Visitor Centre opened in 2006. The arboretum's extensive and important collection of 6,000 trees and plants from across the world is set in a beautiful landscape of parkland, lakes and ponds. The charitable trust that runs the Yorkshire Arboretum also manages Ray Wood.

Listed status

The house is Grade I listed and there are many other listed structures on the estate, several of which are on the Heritage at Risk Register. [11]

Castle Howard as film location

In addition to its most famous appearances in film as Brideshead in both the 1981 television serial and 2008 film adaptations of Evelyn Waugh's novel Brideshead Revisited, Castle Howard has been used as a backdrop for a number of other cinematic and television settings.

In recent years, the castle has featured in the 1995 mini-series The Buccaneers. It was notable in Peter Ustinov's 1965 film Lady L and as the exterior set for Lady Lyndon's estate in Stanley Kubrick's 1975 film Barry Lyndon. It has even featured as the Kremlin, in Galton and Simpson's 1966 film The Spy with a Cold Nose. Rooms (Great Hall Entrance, Turquoise Drawing Room) were used for indoor scenes in Death Comes to Pemberley (TV series 2013).

In 2003, a Time Team episode tried to discover traces of the old settlement of Henderskelf that had been demolished to make way for the castle.

The castle and its grounds were used as the setting for the Bollywood film Shaandar and the 2006 film Garfield: A Tail of Two Kitties.

The castle and mausoleum were used as the setting for the 2018 Arctic Monkeys video Four Out of Five.

The castle is used as the setting for Clyvedon House, family seat of the Duke of Hastings, in the Netflix series Bridgerton (2020).

Gallery

Monument to 7th Earl of Carlisle, 1869-70 by Frederick Pepys Cockerell

Monument to 7th Earl of Carlisle, 1869-70 by Frederick Pepys Cockerell Approach with Carrmire Gate c.1730 by Nicholas Hawksmoor and Pyramid Gate 1719 by Vanburgh, wings added 1756 by Daniel Garrett

Approach with Carrmire Gate c.1730 by Nicholas Hawksmoor and Pyramid Gate 1719 by Vanburgh, wings added 1756 by Daniel Garrett The Great Obelisk 1714 by Vanburgh

The Great Obelisk 1714 by Vanburgh North front across great lake

North front across great lake The west wing 1753-59 by Sir Thomas Robinson

The west wing 1753-59 by Sir Thomas Robinson The south front

The south front "Four Faces" statue, Pretty Wood c.1727 by Hawksmoor

"Four Faces" statue, Pretty Wood c.1727 by Hawksmoor Ruins

Ruins Temple of the Four Winds 1724-1726 by Vanburgh

Temple of the Four Winds 1724-1726 by Vanburgh The Pyramid 1728 by Nicholas Hawksmoor

The Pyramid 1728 by Nicholas Hawksmoor The Atlas Fountain 1850, designed by William Andrews Nesfield sculpted by John Thomas (sculptor)

The Atlas Fountain 1850, designed by William Andrews Nesfield sculpted by John Thomas (sculptor) The Bridge 1744, by Daniel Garrett

The Bridge 1744, by Daniel Garrett The Pyramid Gate 1719 by Vanburgh wings added 1756 by Daniel Garrett

The Pyramid Gate 1719 by Vanburgh wings added 1756 by Daniel Garrett The Mausoleum designed by Hawksmoor in 1728-29, started in 1731 completed in 1742

The Mausoleum designed by Hawksmoor in 1728-29, started in 1731 completed in 1742 The Stables courtyard, 1781-84 by John Carr (architect)

The Stables courtyard, 1781-84 by John Carr (architect) The Mausoleum

The Mausoleum Castle Howard Turquoise Drawing Room

Castle Howard Turquoise Drawing Room Castle Howard The Great Hall by Vanbrugh, paintings by Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini, the dome recreated in 1961 after its destruction by fire in 1940 and painted by Scott Ackerman Medd

Castle Howard The Great Hall by Vanbrugh, paintings by Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini, the dome recreated in 1961 after its destruction by fire in 1940 and painted by Scott Ackerman Medd Castle Howard Lady Georgiana's Dressing Room

Castle Howard Lady Georgiana's Dressing Room Castle Howard Lady Georgiana's Bedroom

Castle Howard Lady Georgiana's Bedroom Castle Howard Crimson Dining Room

Castle Howard Crimson Dining Room Castle Howard Bedroom

Castle Howard Bedroom Castle Howard Chapel altered and redecorated in the 1875-78 by William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones

Castle Howard Chapel altered and redecorated in the 1875-78 by William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones Castle Howard Antique Passage by Vanbrugh

Castle Howard Antique Passage by Vanbrugh The Octagon, in the Long Gallery 1802 by Charles Heathcote Tatham

The Octagon, in the Long Gallery 1802 by Charles Heathcote Tatham The Long Gallery 1802 by Charles Heathcote Tatham

The Long Gallery 1802 by Charles Heathcote Tatham Castle Howard from the lake in c. 1910

Castle Howard from the lake in c. 1910 The Carrmire Gate on the approach in c. 1910

The Carrmire Gate on the approach in c. 1910.jpg.webp) South Lake

South Lake

See also

- Hampton National Historic Site, an 18th-century US mansion said to have been inspired by Castle Howard.

- Castle Howard railway station

- A more detailed architectural appraisal of Castle Howard is at John Vanbrugh.

- List of Baroque residences

References

- Castle Howard Estate Limited

- "The Building of Castle Howard". www.castlehoward.co.uk. Archived from the original on 15 April 2010. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- 'The Pride of Yorkshire' exhibition leaflet, Castle Howard, 2010

- Butt, R. V. J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations: details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-508-7. OCLC 60251199.

- Hull Daily Mail, Monday 11 November 1940 p. 3

- "ALVA - Association of Leading Visitor Attractions". www.alva.org.uk. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- "'Brideshead' house Castle Howard goes green". The Daily Telegraph. 31 August 2010. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- Edward W. Leeuwin: Echoes of Arcadia. Rituals in the Arcadian Landscape of Castle Howard. In: Die Gartenkunst 16 (1/2004), p. 73–84. ISSN 0935-0519

- Historic England. "Castle Howard (1001059)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- "Home". Yorkshire Arboretum. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- Historic England. "Castle Howard and East Court (1316030)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Castle Howard. |