Cairns-to-Kuranda railway line

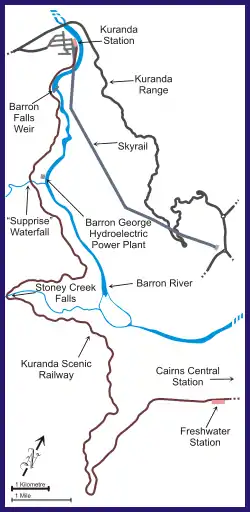

The Cairns-to-Kuranda Railway is a heritage-listed railway line from the Cairns Region to the Shire of Mareeba, both in Queensland, Australia. It commences at Redlynch, a suburb of Cairns and travels up the Great Dividing Range to Kuranda within the Shire of Mareeba on the Atherton Tableland. It was built from 1913 to 1915 by Queensland Railways. Components of it include Stoney Creek Bridge, the Rail Bridge over Christmas Creek, Kuranda railway station, and Surprise Creek Rail Bridge. It was added to the Queensland Heritage Register on 21 August 1992.[1] The railway is used to operate a tourist rail service, the Kuranda Scenic Railway. It forms part of the Tablelands railway line.

| Cairns-to-Kuranda railway | |

|---|---|

Map of the railway | |

| Location | Redlynch to Kuranda (4881), Redlynch, Cairns Region, Queensland, Australia |

| Coordinates | 16.8631°S 145.6631°E |

| Design period | 1914 - 1919 (World War I) |

| Built | 1913-1915 |

| Official name | Cairns Railway, Section from Redlynch to Crooked Creek Bridge, Cairns to Kuranda Railway, Stoney Creek Bridge, Rail Bridge over Christmas Creek, Kuranda Railway Station, Surprise Creek Rail Bridge |

| Type | state heritage (built) |

| Designated | 21 August 1992 |

| Reference no. | 600755 |

| Significant period | 1887-present |

| Significant components | signals, office/s, turntable, signal box/signal cabin/switch house/mechanical points (rail), garden - bed/s, toilet block/earth closet/water closet, shed - shelter, shed - goods, residential accommodation - station master's house/quarters, office/s, toilet block/earth closet/water closet, shed - shelter, ramp, shed - storage, drain - storm water, tank - water, shed - shelter |

| Builders | Queensland Railways |

Location of Cairns-to-Kuranda railway in Queensland  Cairns-to-Kuranda railway line (Australia) | |

History

The Redlynch to the Crooked Creek Bridge portion of the Cairns-to-Kuranda railway constitutes most of the second section (Redlynch to Myola) of a planned railway line to Herberton. It ascends the coastal range and travels around Stoney Creek Gorge and through the Barron Gorge, to a height of 327.7 metres (1,075 ft) at Barron Falls railway station. It proceeds through Kuranda railway station 21.7 kilometres (13.5 mi) from Redlynch, to Crooked Creek Bridge 23.2 kilometres (14.4 mi) from Redlynch. Built between April 1887 and June 1891 through a steep and slip-prone landscape, the section is a feat of engineering which in 2011 included 15 concrete-lined tunnels and 39 timber or steel bridges (from Redlynch up to and including Crooked Creek Bridge).[1]

Mining provided the original impetus for building a railway line up to the Atherton Tablelands from Cairns. Cooktown thrived as a port for the Palmer River goldfield, discovered in 1873, but it was too far from the Hodgkinson goldfield, discovered further south in early 1876. Trinity Bay was chosen as the port for the Hodgkinson; the first settlers arrived in October 1876 and Cairns became a port of entry on 1 November 1876.[2] However, the founding of Port Douglas in 1877 almost stifled Cairns, as the former provided an easier access route to the Hodgkinson. When tin was discovered on the Wild River in 1880, the road from Port Douglas to Herberton was also preferred to the pack tracks from Cairns.[1]

Cairns salvaged its economy after a heavy wet season in early 1882 closed the road from Port Douglas, resulting in calls for a railway from Herberton to the coast. Linking mining areas to ports by railway was already Queensland Government policy. In August 1877 the Queensland government had approved three railways to connect mining towns to their principal ports: Charters Towers to Townsville (Great Northern railway line); Mount Perry to Bundaberg (Mount Perry railway line); and Gympie to Maryborough (North Coast railway line).[1]

The Minister for Works, John Macrossan, commissioned the explorer Christie Palmerston to find a route from Herberton to Cairns or Port Douglas; but in August 1882 Palmerston reported that there was no natural route. The Johnstone Divisional Board commissioned Palmerston to find a route to Mourilyan Harbour during late 1882, but as the Board failed to pay him, Palmerston did not report his findings.[1]

The search for a rail route continued, with the Railway Department's surveyor, George William Monk, arriving in Cairns in April 1883. Surveys of the various possible routes to Cairns, Port Douglas and Mourilyan were carried out by Monk and other surveyors and in late 1884 Robert Ballard, the Railway Department's Chief Engineer (Central and Northern Railway Division) reported to the Commissioner for Railways the cost would be the same from any of the three rival termini, but Cairns was the better port.[3] The preferred route from Cairns was via the Barron Gorge, although the Mulgrave River had also been considered. The government's decision in favour of Cairns was announced, much to the outrage of Port Douglas residents, on 10 September 1884. The decision to build the railway from Cairns ensured that it became the preeminent town in far north Queensland; yet the Barron Gorge was chosen in ignorance of its unstable geology,[4] which later proved costly in both money and lives.[1]

Parliament approved plans for the first 24 miles (39 km) of the Cairns to Herberton railway in late 1885[5] but the contract let to Messrs PC Smith and Co. on 1 April 1886 was only for the first 8 miles (13 km). On 10 May 1886, the Premier Sir Samuel Griffith turned the first sod. Smith lacked the experience for even such a short section and McBride and Co took over the contract in November 1886. The government then had to take over from McBride in July 1887.[6] The first section opened on 8 October 1887 and the terminus was soon named Redlynch. In 1911 a deviation shortened the first section, meaning that Redlynch was no longer at the eight-mile mark from Cairns.[1]

When the railway line opened, there were a number of railway sidings along the line: Stratford (5 miles from Cairns), Lily Bank (6 miles from Cairns), and Richmond (7 miles from Cairns). Richmond Siding was renamed Freshwater Siding (later Freshwater railway station) in January 1890.[7] The development of the railway line had encouraged land developers to release a land subdivision called Richmond Park Estate near the railway line and Freshwater Creek, which was sold from 1886 with advertising featuring the forthcoming Richmond Park railway station and its ten minute rail journey to Cairns; this explains the original name of the siding.[8]

The ascent of the range to Kuranda began with the awarding of the 15 miles (24 km) second section of the contract (Redlynch to Myola) to John Robb of Melbourne in January 1887 for £290,984.[9] Robb was an experienced contractor, and brought hundreds of men to the job. Robb also had mining, rural and business interests in South Australia, New South Wales and Melbourne, where he was a founding director of the Federal Bank in 1881. The Kuranda ascent was his most significant work, but his company's other contracts included Tasmania's and Western Australia's first railways. He returned home to Toorak when he left Cairns, was declared insolvent in October 1894 and died in May 1896, aged 62.[1][10]

Work on the second section began in April 1887. To aid construction Robb built a 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) branch line from Redlynch to the main construction camp at Kamerunga beside the Barron River, and public trains extended to Kamerunga from 20 October 1888. Robb planned to work at various points along the line simultaneously, and tracks ran from Kamerunga to the sites for tunnels 2, 3, 6 and 9, to the Stoney Creek Bridge site and to The Springs.[1][11]

One feature of interest near the beginning of section two is Horseshoe Bend, located after the third timber bridge from Redlynch. In December 1888 the embankment at the bend was described as 51 feet (16 m) high, 15 feet (4.6 m) wide at the top, and 170 feet (52 m) wide at the base, and was sown with Couch grass (Cynodon dactylon) on the sides.[12] The embankment has since been widened using landslide material. Section two used Horseshoe Bend to gain height, followed by the line ascending to the top of Barron Falls. The section then followed the Barron River to Kuranda, terminating at Myola, almost 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) past Kuranda. Nineteen tunnels had been originally planned between Horseshoe Bend and Barron Falls Station, but four (two between Stoney Creek and Tunnel 14 and two at Red Bluff) were subsequently replaced by cuttings. Sand from the bed of the Barron River was used as the base material for concrete work on the second section; all the tunnels were concrete lined, and culverts and drains were also built in concrete.[1]

The Cairns Railway's range ascent tunnels represent the largest group of tunnels in Queensland and were the 24th to 38th of the 64 tunnels opened in Queensland from 1866 to 1996.[13] By 30 January 1889 tunnels 1 and 2 were finished; Tunnel 3 was in a forward state, while 4-9 and 12-13 were ready for lining. Tunnels 10 and 11 had headings through only, while tunnels 16 and 19 were not yet opened. Work was authorised on the redesigned and lengthened Tunnel 19 in December 1889. Due to the cancellation of four tunnels, tunnels 16 and 19 were renumbered as today's tunnels 14 and 15.[1]

As well as tunnels, bridgework was a major element of the construction work on the second section. The total length of steel required to complete the bridgework was around 800 feet (240 m). The steel work was all cut, fitted and partly riveted by Walkers Ltd of Maryborough. In 2011 the steel bridges between Redlynch and Kuranda included: six with lattice girders; plus Bridge 42 (1890), where fishbelly plate cross- girders have been reused as main span members; Bridge 50 over Mervyn Creek (which replaced an earlier timber bridge in the 1920s); and Jumrum Creek Bridge (Bridge 51), which although mainly timber has a steel central span (the bridge was reconstructed in 1962). There were also five very short steel bridges by 2011. About 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) past Kuranda is Crooked Creek Bridge, which in about 1900 reused (shortened) plate girders from the 1867 Bridge 51 on the Main Range. The bridge has been strengthened with new steel piers either side of the concrete pier, and its replacement steel cross girders also originally came from Bridge 51 on the Main Range.[1][14]

There were 24 timber trestle bridges extant in 2011, but none of these retain their original timber. The local scrub hickory originally used in the bridges was of poor quality, requiring replacement work in the 1890s to 1900s.[15] Components of the timber bridges are also gradually being replaced with steel, due to the scarcity of suitable hardwood, and over the years some bridges have been replaced with concrete culverts.[1]

The steel bridges have retained their integrity to a greater degree. The bridges with highest heritage significance are the steel lattice-girder bridges; all built during the construction of the second section. Three are located at Stoney Creek, Surprise Creek, and Christmas Creek. The other three are Bridge 21, the first steel bridge on the section, located between Tunnel 3 and Tunnel 4; Bridge 23, after Tunnel 9; and Bridge 29 between Stoney Creek Station and the Stoney Creek Bridge. The bridges have been renumbered since construction: for example, today's Bridge 21 was originally called Bridge 11.[1]

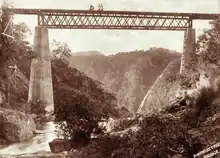

Stoney Creek Bridge

Stoney Creek Bridge (originally bridge number 26, now bridge 30), in front of Stoney Creek Falls, is built on a 4-chain (260 ft; 80 m) radius curve and was designed by the government engineer John Gwynneth.[16] The design is unique in Queensland, the curve being the only way to avoid tunnelling. By the end of 1887 the concrete foundations on which the wrought iron trestles (Phoenix columns) were erected were well underway.[17] It is one of only two Queensland railway bridges constructed with wrought iron trestles, the other being Christmas Creek Bridge, further up the line.[18] A visit to Cairns by the Governor of Queensland, Sir Henry Wylie Norman, in April 1890 was taken as an opportunity to inspect the construction works. A marquee, covering a banquet table and open to the waterfall, had been set up on the almost completed Stoney Creek Bridge with planks laid over the sleepers. There were no speeches due to the roar of the waterfall immediately behind the bridge.[19] The bridge passed load testing on 30 June 1890.[1]

In the period of the early 1900s large quantities of rock in the vicinity of the bridge were removed, due to the risk of rock falls. Work was carried out in 1916 to strengthen riveted connections, and in 1922 timber longitudinals were substituted for the ballast flooring of the original bridge, to reduce corrosion problems.[1]

Stoney Creek Bridge is one of the most photographed bridges in Australia due to the spectacular beauty of its location. Historian John Kerr called it "the best-known structure on a line with the most spectacular scenery on the Queensland Railways".[20] Trains would halt on the bridge and passengers could leave the train to walk along the bridge for a short period of time. In order to strengthen and improve the safety of the bridge, in the late 1990s new steel longitudinals were added under the bridge, the timber decking was replaced with steel grating and the walkways at the sides of the bridge were widened to improve maintenance access. The legs of the iron trestles were also reinforced.[1]

Surprise Creek Bridge

Surprise Creek Bridge (originally number 36, now number 46) was constructed in 1890-91. Originally the main span had timber approaches, but these were replaced in the late 1890s by pin-jointed steel lattice trusses recycled from an older bridge. New interior steel longitudinals were added under the bridge in the late 1990s.[1]

Christmas Creek Bridge (originally number 37, now 48) was built in 1891. Some cross girders have been replaced after they rusted out.[1]

The construction of the section's tunnels and bridges required a lot of labour. Queensland signed a special treaty with Italy in order to obtain indentured Italian workers, and many Irishmen were employed. At the height of construction up to 1500 workers were employed along the length of line.[1]

The tunnelling work was done by hand. The usual danger from the extensive use of explosives in the tunnels and cuttings was increased by the unstable nature of the rock and the steep drop down the side of the Barron Gorge. The average slope of the ground was 45 degrees, covered with a disjointed layer of decomposed soil and rock varying in depth from 5 to 8 metres (16 to 26 ft). Robb had to dig deep into hillsides to find solid ground, and multiple deviations from the original surveyed route also increased his costs. Red Bluff and Glacier Rock were exposed when earth, rocks and trees were removed,[21] again by hand, from above the line (escarpments had to be cleared and levelled back).[1]

At least 23 accidental deaths occurred during construction of the second section, the main causes being premature blasting, injuries from rock falls and cave-ins, and falling.[22] One man, Giovanni Zappa, fell 250 metres (820 ft) into the Barron Gorge in September 1888. Other deaths resulted from malaria, ticks, scrub typhus (mites), dysentery, fevers, and snakes. Hundreds of men were injured, but despite the existence of the Queensland Employers' Liability Act 1886, only one worker was compensated.[23] Other labour issues led to the formation of a trade union - the United Sons of Toil, which called a strike in late 1890.[1][24]

During construction navvies' camps were established at most of the cuttings and at each of the bridges or tunnels along the range section. The main townships other than Kamerunga included New Cairns (later Jungara); Rocky Creek Falls (between tunnels 8 and 9); Stoney Creek; The Springs (between tunnels 14 and 15); Red Bluff; and Camp Oven Creek (just past Tunnel 15).[25] There were also small towns at Tunnel 3, Surprise Creek, and Gray's Pocket on Rainbow Creek above the falls.[26] These small townships of tents and portable buildings usually had at least one hotel, a general store, and a boarding house for single men. At Stoney Creek Falls, Patrick Paton's hotel possessed a billiard room, dining room, bar, ballroom and 28 double rooms, while New Cairns below the Horseshoe Bend had a hotel, sawmill, and at least two general stores. In all 26 hotels were licensed to operate from Kamerunga and Redlynch to Kuranda from 1886 to 1888.[1][27]

Due to the difficulty of the project both the contract price and the completion date of 26 July 1888 were greatly exceeded. After a very wet season in 1891 there was major damage to the track; about 140 metres (460 ft) of ground slipped and an embankment at one tunnel collapsed and required the ground to be drained.[1]

When Tunnel 15 and Surprise Creek Bridge were completed by 14 March 1891, it marked the end of major works. The last rails were laid for the second section in May 1891 and the line opened for goods traffic to Myola on 15 June; and for passengers 10 days later.[1][28]

Despite the difficulties encountered during construction, the line proved to be well built, a tribute to Willoughby Hannam, Chief Engineer for Railways, Northern and Carpentaria Division (from 1885 to 1889), who had to survey many deviations when the original route proved impossible to construct. Hannam was succeeded by Chief Engineer Annett.[1][29]

In common with all railway contracts, the price was calculated by multiplying the quantity of each type of work required by the quoted price and summing up the individual amounts. If the survey was altered to require more excavation, the government paid for the extra at the schedule rate. The unstable nature of the terrain in the second section meant that the slopes of cuttings and banks had to be reduced. As Robb had to remove five times as much material as originally estimated for cuttings and tunnels, he was eventually paid £880,406. He claimed a further £262,311, but only received £20,807 of this after arbitration. With rails and other costs, the second section cost the Queensland Government £1,007,857; the most expensive line in Queensland.[1][30]

The huge cost overrun on the second section, along with the financial depression of the early 1890s, delayed the Cairns Railway's extension to Herberton. The contract for section three (Myola to Granite Creek/Mareeba) was awarded to Alexander McKenzie & Co. in early 1891 (Robb's tender failed) and this section was opened on 1 August 1893.[31] A lack of funding meant that the line stopped at Mareeba for some time. It did not open to Atherton until 1903 and to Herberton until October 1910. By this time timber and agriculture, rather than tin, drove the railway's extension and the line was extended past Herberton. It opened to Tumoulin in July 1911 and finally to Cedar Creek (Ravenshoe) in December 1916. Meanwhile, a branch line from Tolga opened to Yungaburra in March 1910, to Malanda in December 1910, and to Millaa Millaa in December 1921.[1][32]

.JPG.webp)

Kuranda railway station

By 1891 Kuranda Station was the most important station on the second section. It had also become a tourist destination due to its proximity to the Barron Falls. Kuranda was surveyed in 1888 in anticipation of development which would accompany the arrival of the railway and the first station buildings were relocated from Kamerunga after services to the latter location ended in 1891. The station master's house from Kamerunga was also moved to Kuranda, in 1908.[33] By 1913 Kuranda Station included (from north-west to south-east) the office, a separate refreshment room (operated by the proprietor of the Kuranda Hotel from 1894), men's and women's toilets and a goods shed. Construction of the Chillagoe Company's private railway lines from Mareeba to Chillagoe and Forsayth, during 1898-1901 and 1907-1910 respectively,[34] increased freight traffic through Kuranda, and tourist traffic was also increasing prior to World War I.[1]

.JPG.webp)

A 1910 report had recommended a new station building at Kuranda on an island platform that could be made ornamental by planting trees. Vincent Price was in charge of the architectural section of the Railway Department's Chief Engineer's Office when the passenger station block, described by the Chief Engineer as "after the style of a Swiss Chalet, the idea being to make Kuranda a show station",[35] was designed in 1911. Modified plans were drawn in 1913-14, and included the main station building (with booking lobby, booking office, waiting shed, ladies' toilets, passage, refreshment room, kitchen, pantry, scullery and kitchen yard); a signal cabin; and a utilities block (with men's toilet, porter's room, store room, and lamp room). Each of these three buildings was constructed of precast concrete units, in a Federation style with a Marseilles terracotta tile roof.[1]

Expansion of the station began in 1913 and continued into 1915. Changes involved the extension of the platform and yard, the signalling and interlocking of the station and the construction of a timber overbridge and new station buildings. The main station building was "nearing completion" by September 1914.[36] Its main spaces survive, although the former refreshment room and kitchen are now the gift shop and cafe, and the former kitchen yard is now a lean-to extension.[1]

One of the earliest stations to be built in Australia using standard precast concrete units, Kuranda is the second oldest remaining example of its type in Queensland. Two earlier examples at Northgate (1911–12) and Chelmer (1913) in Brisbane have both been demolished, while another example opened at Ascot (Eagle Farm Racecourse) in February 1914[37] survives. A luggage lift from the overbridge to the platform, installed in 1915, was demolished after 1939, but a new lift with a shed at its base has been built since 1994.[1]

The signal cabin included a fully interlocking McKenzie and Holland 37-lever mechanical signal frame (still extant). Before railway "safeworking" systems were computerised and centralised in Queensland, mechanical signals were controlled from signal cabins, which dealt with the traffic on a particular block of railway line. Signal cabins coordinated signals that indicated whether or not a section of track was clear of other traffic. Early signals were mechanical, while later signals were operated electrically. The most common form of mechanical signal was the semaphore signal. These consisted of a metal framed tower with one or more arms that could be inclined at different angles, with the arm at the horizontal signalling "danger", or do not proceed. Examples of this form of signalling system survive at Kuranda Station. At night, lights were necessary, and kerosene lamps with movable coloured spectacles displayed different colours, including green (proceed), yellow (prepare to find next signal red), and red (stop).[1]

To coordinate signals so that it is impossible to give a "clear" signal to a train unless the route is actually clear, the signals could be interlocked. An interlocked yard is a railway yard where semaphore or coloured light signals are controlled in such a way that the signals will not allow a train to proceed unless the points that operate in conjunction with the signals are correctly set. A mechanical interlocking device, located under a mechanical signal frame, is a system of rods, sliding bars and levers that are configured so that points cannot be changed in conflict, thus preventing movements that may cause a collision or other accident.[1]

Although 169 Queensland railway stations had interlocking by 1918,[38] mechanical interlocking technology eventually became obsolete, as electrical interlocking or electro-pneumatic systems replaced it. Computerised Centralised Traffic Control (CTC) signalling systems now control most of the network.[1]

As well as the station buildings, signals and interlocking, the station was beautified. The ornamental planting proposed in the 1910 scheme was developed by George Wreidt and Bert Wickham, both station masters at Kuranda. The tropical vegetation in the platform's gardens and under the platform shelters helped to soften the lines of the station, which first won the Northern Division of the Railways' Annual Garden Competition in 1915 and was so often the winner in subsequent years that it became folklore that Kuranda won every year.[1]

By 1927 the station included a goods shed to the south-east of the main platform, and a turntable at the north-west end of the station. The current turntable is apparently smaller than the original, which was relocated to Port Douglas.[14] Elements that were present in 1932 which no longer exist include a motor shed by the turntable, and signalman's, ganger's and waitresses' quarters to the south of the station near Arara Street.[1]

Due to the position of the station at the top of the range climb the station played a key role in freight handling. Extra trains would usually run to Kuranda where their load was transferred, as trains operating west of Kuranda were able to haul double the load they could carry up the range.[1]

As well as freight services, tourist trains ran to Kuranda, although the tourist service was not a formal part of the public timetable of the Queensland Railways until the 1960s.[39] The tourist potential of the second section was recognised early on, with Cairns Alderman Macnamara in September 1887 calling it a great engineering feat, which "would prove a great attraction to tourists from all parts of the globe".[40] In 1893 local representatives from the Barron Divisional Board met with the Railway Commissioners to discuss a proposed viewing stop on the line for the Barron Falls.[1][41]

The growth of tourism in Kuranda was linked to the popularity of the passenger services of the Adelaide Steamship Company, the Australian United Steam Navigation Company and Australian Steamships (Howard Smith Ltd). Travellers from Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne came to Cairns by ship until the opening of the rail line to Brisbane in 1924. In the early 20th century Queensland Railways published a brochure called "Train Trips While the Steamer Waits" which urged tourists not to miss the unsurpassable natural beauty of the mountains, best seen by taking the train to Kuranda. Another early tourist booklet "The Glory of Kuranda" describes the station as the most picturesque in Queensland. In the late 1930s a "Grandstand Train" ran to Kuranda. This had special carriages with two rows of tiered seats both looking out the same side, through scenic windows.[1]

Tourist travel stopped during the World War II. However, Kuranda was one of the busiest stations at this time handling freight for the many troops which were stationed on the Atherton Tablelands from early 1943 for rest, rehabilitation and training in a malaria-free environment close to New Guinea. Traffic at this time was so great that the road from Cairns to Kuranda was constructed to relieve congestion.[1]

Diesel-electric locomotives were introduced onto the Cairns-Kuranda railway in 1959, and tourism recovered after World War II, with a 100 percent increase in passengers between 1965 and 1975.[42] During the 1960s Kuranda became an alternative lifestyle centre, and the Sunday Markets which began in the late 1970s boosted tourism to the town and the railway station, as did the building of the Skyrail Rainforest Cableway in the mid 1990s.[43] By 2003 some 500,000 people visited Barron Gorge National Park each year via the Kuranda Scenic Railway,[44] often returning on the Skyrail.[1]

The tiled roofs of the station buildings were replaced with plain iron sheet in 1961 which was in turn replaced by ribbed metal sheeting in 1989-90. The southern section of the foot bridge was rebuilt in steel in 1990, and the northern section has since also been replaced in steel. The station master's house survives just to the northwest of the railway station, although its verandahs have been enclosed.[1]

Over time, other stations between Redlynch and Myola have included Jungara, Stoney Creek, The Springs, Barron Falls, Hydro, and Fairyland. Only Redlynch, Stoney Creek, Barron Falls and Kuranda retain any built structures, and those at Barron Falls are modern.[1]

Redlynch railway station

%252C_2018_02.jpg.webp)

In 2011 the remaining infrastructure at Redlynch Station included a station building with garden area, a men's toilet, and a loading bank. The core of the station building existed by 1890, although it originally had a curved roof.[45] The building may date from the opening of the first section of the Cairns Railway in 1887, as in August 1888 plans were afoot to erect station buildings at Kamerunga "similar to those at Redlynch".[46] The Kamerunga station building also had a curved roof and was later moved to Kuranda when the second section was opened in 1891. The steel pipe framing under the current verandah at Redlynch was once used to hang pot plants.[1]

An 1899 plan of the Redlynch station building included a store (2.4 metres (7 ft 10 in)), waiting shed (3 metres (9.8 ft)) and an office (3 metres (9.8 ft)). Around this time the office was extended another 2.4 metres (7 ft 10 in) to the south-west, with a ladies room (3.7 metres (12 ft)) added at the south-west end of the building. There was a partition for a toilet in the latter, which seems to have survived when the ladies room was converted into a goods area c. 1954. At this time the store at the north-east end of the building became the new ladies room, and a separate men's room was constructed north-east of the station building.[1]

The wall between the office and the former ladies room has since been removed, and the roof is now gabled rather than curved. A World War II photo of the building shows weatherboard cladding at the north-east end. A goods shed present in the 1954 site plan, north-east of the shelter shed, is no longer extant. A timber stage was located west of the shelter shed at the end of a siding, on the site of the present car park. A station master's cottage was located within the turning triangle to the south-west of the shelter shed, but this has been replaced by modern buildings for a Queensland Rail (QR) maintenance gang.[1]

As at 2018, the station building still exists but is fenced off preventing public access.

Stoney Creek railway station

At Stoney Creek Station, a gatehouse was erected in 1909. By 1911 the complex included an open shelter shed with an enclosed office, plus a ladies' room with a curved roof to the east.[47] By 1936 the complex consisted of the shelter shed; ladies' room; a water tank for steam trains, supplied from Stoney Creek Falls and a sand shed (west end of station); plus two fettler's camping quarters and a trolley and tool shed (either side of track, east end of station). Only the shelter shed, the water tank and the sand shed survive. The latter was once used to refill sandboxes on trains, which enabled dry sand to be dropped onto the tracks to assist traction. In the 1980s a telephone line and its poles were removed. The siding is used by QR maintenance gangs to wait for tourist trains to pass, and the shelter shed is used when it is raining. Exotic plantings in the station's gardens have being replaced by natives, in keeping with the National Park, although mature mango trees of heritage significance have been retained.[1]

For many years, Stoney Creek was notable for its gardens of coloured tropical foliage. This site was always expected to have tourism value - during construction, a piano was laboriously brought up the range to the Stoney Creek Hotel. The owner optimistically expected that future tourists would stay at his hotel to view the falls.[48] The Kuranda Scenic Railway (running from Cairns to Kuranda) no longer stops at this station.[1]

Since construction of the second section, the weather and geology have continued to impact on the line. There were landslides during 1894, 1896, 1904, 1909 and 1910, but the biggest disruption occurred in the summer of 1910-11. Slips in December 1910 resulted in a tramway being built to bypass Tunnel 10, which was blocked on the Kuranda side, and the line was closed for 10 weeks. There were more slips and washouts in late March 1911, with interruptions to traffic until the end of April 1911.[1]

In 1939 18 metres (59 ft) of the Cairns end of Tunnel 14 required reinforcing, and the thinner concrete formwork is visible. There were also serious disruptions in March–April 1954 due to a landslide. The continued threat of rock falls and slips have meant that rock anchors have been deployed on boulders above the Stoney Creek Falls, and large barrier fences have been erected in places above the line.[1]

The original rails were replaced in the 1990s, from 60 pounds (27 kg) per 1 yard (0.91 m)) weight, to 41 kilograms (90 lb) per 1 metre (3 ft 3 in). One in every four sleepers are now steel, with a one in two ratio on curves with a radius under 120 metres (390 ft). Some cuttings were also widened in the 1980s and 1990s. Most cuttings are in earth or rock, but some have concrete lining or stone pitching in parts. Some timber bridge components, such as the piles or headstocks of trestles, have been replaced by steel, or whole trestles have been replaced by concrete piers. There are a large number of small open concrete drains passing under the line. Early cast concrete pipes and culverts (not reinforced) along the line will be replaced with reinforced concrete pipes if the originals collapse.[1]

Description

The section of the Cairns Railway from Redlynch to Crooked Creek Bridge commences at Redlynch railway station, which is located to the north-west of the Cairns CBD, at a distance of 11.6 kilometres (7.2 mi) by rail from Cairns Railway Station.[1]

Redlynch railway station

Redlynch railway station is located at the intersection of Kamerunga Road and Redlynch Intake Road. The main station building (unused in 2011), north-east of the intersection, is adjacent to Kamerunga Road and faces away from the road towards the railway line. The building is elevated on steel poles from street level to the level of the platform, and is rectangular, timber framed and chamferboard clad. Its gabled roof extends on the railway side to form a verandah, which has extra support in the form of steel pipe framing.[1]

Inside, the walls are single skinned. The south-west end of the building contains the office and the former goods room, with a small walled cubicle at the south-west (goods room) end. The partition wall between the office and the goods room has been removed. There are two windows (one casement and one with timber louvres) at the south-west end of the space, along with a door to the platform and a casement window to the south-east (Kamerunga Road) elevation. The office space, which retains some timber counters, has a casement window and a modern sliding window on the south-east side, two sash windows on the north-west elevation, and a stable door and ticket window on the north-east side, through to the waiting shed. The waiting shed retains its bench seating, and has a glass-louvre window to the south-east elevation and a timber double folding door to the platform. North-east of the waiting shed is the ladies toilet, with a doorway to the platform and a small glass louvre window to the south-east. The remains of gardens, with concrete retaining walls to Kamerunga Road, are located south- west of the station building.[1]

Just north-east of the station building is a separate men's toilet block, timber framed and clad with chamferboard. It is elevated on concrete stumps and has a skillion roof. A doorway towards the platform is shielded by a corrugated iron clad entrance porch, and there is a glass louvre window on the south-east elevation.[1]

North-east of the station building and men's toilet block and north of the railway line, is an earth loading bank with a concrete retaining wall. To the south-west of the station building, past the railway crossing, the western arm of a turning triangle survives, with modern buildings within the triangle. These modern buildings are not of cultural heritage significance.[1]

From Redlynch Station, the railway line heads south past Jungara to Horseshoe Bend, before heading north along the eastern side of the Lamb Range and turning west into Stoney Creek Gorge. Between Redlynch and Stoney Creek Station there are 13 tunnels and 16 bridges. The first bridge (deck type) is located at a distance of 12.06 kilometres (7.49 mi) from Cairns. It uses timber girders on timber trestles (some trestle piles and headstocks have already been replaced with steel); this is the form used by the majority of timber bridges on the section, although some use single-span timber girders between concrete abutments. A second timber bridge, with a concrete pier, exists at 13.05 kilometres (8.11 mi). The site of Jungara Station is passed at 13.82 kilometres (8.59 mi), with a timber trestle bridge at 14.77 kilometres (9.18 mi), just before Horseshoe Bend, a 5 chains (330 ft; 100 m) curve with a large earth embankment. There are two more timber trestle bridges at 15.31 kilometres (9.51 mi) and 16.55 kilometres (10.28 mi), plus a single span timber girder bridge between concrete abutments at 16.95 kilometres (10.53 mi), before reaching the first tunnel at 17.12 kilometres (10.64 mi). Tunnel 1 is concrete lined (as are all the tunnels), straight and 66 metres (217 ft) long.[49] Tunnel 2, located at 18.42 kilometres (11.45 mi), is straight with a left curve at the uphill end and 76 metres (249 ft) long; while Tunnel 3 is at 19.11 kilometres (11.87 mi) (curve left, then straight, 109 metres (358 ft)).[1]

The bridge at 19.31 kilometres (12.00 mi) (Bridge 21) is a deck-type steel lattice girder bridge with timber trestles on the approach spans, and wrought iron piers.[50] It is immediately followed by Tunnel 4 at 19.39 kilometres (12.05 mi) (straight, 93 metres (305 ft)). Tunnel 5 is located at 19.64 kilometres (12.20 mi) (curve left, 92 metres (302 ft) long); Tunnel 6 at 19.91 kilometres (12.37 mi) (straight, 111 metres (364 ft)); and Tunnel 7 at 20.06 kilometres (12.46 mi) (curve left, 50 metres (160 ft)). There is a timber trestle bridge just before Tunnel 8, the latter being located at 20.25 kilometres (12.58 mi) (curve left, 103 metres (338 ft)), and Tunnel 9 is at 20.53 kilometres (12.76 mi) (straight then curve left, 179 metres (587 ft)). There is a high embankment between tunnels 8 and 9.[1]

Travelling west along the southern side of the Stoney Creek Gorge, at 20.72 kilometres (12.87 mi) there is a second steel lattice girder bridge (Bridge 23), with timber trestles on the approaches and two concrete piers, which is followed by two timber trestle bridges (the first also has one concrete pier) prior to Tunnel 10 at 21.06 kilometres (13.09 mi) (straight then curve left, 119 metres (390 ft)). Tunnel 11 is at 21.30 kilometres (13.24 mi) (curve left, 83 metres (272 ft)), and is followed by two very small single span steel bridges over concrete drains at 21.58 kilometres (13.41 mi) and 21.60 kilometres (13.42 mi). Kelly's Leap follows, where a modern rock fall barrier has been erected near an early open concrete drain. These are followed by timber trestle bridges at 21.76 kilometres (13.52 mi) and 21.92 kilometres (13.62 mi), and then Tunnel 12 at 22.04 kilometres (13.70 mi) (curve right then straight, 81 metres (266 ft)). There is a timber trestle bridge at 22.18 kilometres (13.78 mi), followed by Tunnel 13 at 22.47 kilometres (13.96 mi) (straight then curve left, 88 metres (289 ft)).[1]

Stoney Creek railway station

Soon after Tunnel 13, Stoney Creek Station is reached, at 22.53 kilometres (14.00 mi). Within a cutting a siding branches off the main line and runs parallel and to the south of the main line, rejoining at the west end of the station. A shelter shed with an enclosed office in its south-east corner is located between the siding and the main line. The shed has an earth floor and a hipped roof, and the timber walls and posts are mounted on concrete wall and post bases. The timber framed walls of the office section are single skinned, and are clad with chamferboards. The office has open window frames on the south and west sides, a pivoting timber window to the east side and a timber door on the north side. The main open space of the shed has a single skinned timber wall (with a gap above the concrete wall base) on the south side, which has an open window frame.[1]

South of the siding, at either end of the station, are large stone-pitched open drains. At the west end of the station, uphill of where the siding rejoins the main line, is a water tower, with a sand shed to its west. The two-tier cast iron square water tank stands on timber supports, with its disconnected jib lying underneath. The skillion- roofed sand shed is clad in corrugated iron, with two doors at the front, and stands on concrete base walls.[1]

Stoney Creek bridge

Between Stoney Creek Station and Kuranda there are another two tunnels, and 22 bridges. After leaving Stoney Creek Station there is a steel lattice girder bridge (Bridge 29) with wrought iron piers on concrete bases at 22.92 kilometres (14.24 mi). This is followed by Stoney Creek Bridge (Bridge 30) at 23.15 kilometres (14.38 mi), with seven spans of steel lattice girders supported by wrought iron trestles on concrete footings. A concrete pier and two timber trestles support the uphill approach spans. This bridge has a total length of 88.4 metres (290 ft), with a curved track.[1]

After Stoney Creek Bridge the line proceeds north-east along the northern side of the Stoney Creek Gorge, over two timber trestle bridges at 23.39 and 23.78 kilometres (14.53 and 14.78 mi), plus a single span timber bridge at 23.89 kilometres (14.84 mi) and a single span steel bridge at 24.54 kilometres (15.25 mi), before entering Tunnel 14 at 24.69 kilometres (15.34 mi) (curve left, 85 metres (279 ft)). Glacier Rock looms to the north of the line at this point. The line then passes the site of The Springs Station before cutting alongside The Red Bluff and entering the Barron Gorge. There is a single span steel bridge at 25.49 kilometres (15.84 mi), and a modern footbridge over the line (Douglas Track) before two timber trestle bridges at 25. km and 25.95 kilometres (16.12 mi). By this point the line has turned to the north-west.[1]

Another timber trestle bridge is encountered at 26.27 kilometres (16.32 mi), before Tunnel 15 at (in its middle) 26.55 kilometres (16.50 mi) (curve left, straight, curve right, straight, curve left, 430 metres (1,410 ft)). There is a timber trestle bridge at 26.98 kilometres (16.76 mi), followed by a timber bridge with a concrete pier at 27.55 kilometres (17.12 mi). At 27.72 kilometres (17.22 mi) is a small steel deck-type bridge using fishbelly plate girders (Bridge 42) supported mid span by a concrete pier; this is followed by a single span steel bridge at 27.86 kilometres (17.31 mi) and two single span timber bridges at 28.22 and 28.53 kilometres (17.54 and 17.73 mi).[1]

Surprise Creek bridge

The Surprise Creek Bridge, at 28.7 kilometres (17.8 mi), is a 72.54 metres (238.0 ft) long steel lattice girder bridge set on tall concrete piers at the head of a waterfall. The approach spans are pin jointed. This is followed by a timber trestle bridge at 29.16 kilometres (18.12 mi), and then Christmas Creek Bridge at 29.23 kilometres (18.16 mi). The sixth and final steel lattice girder bridge on the section, the Christmas Creek Bridge is 39.6 metres (130 ft) long, with wrought iron trestles.[1]

The line continues north past Forwards Lookout and then passes Robb's Monument, a stone monolith east of the track. There is a timber trestle bridge at 29.93 kilometres (18.60 mi), before Bridge 50 over Mervyn Creek at 30.18 kilometres (18.75 mi), with steel girders on concrete piers. Barron Falls Station, between 30.65 kilometres (19.05 mi) and 30.82 kilometres (19.15 mi), includes a modern platform, shelter shed and lookout over the Barron Falls, as well as a footbridge over the line at the south end of the station. The shelter shed has a similar timber roof frame to the shelter at Stoney Creek Station, although it uses steel posts. The line continues along the west bank of the Barron River past the site of Hydro Station, to Jumrum Creek Bridge at 32.54 kilometres (20.22 mi). This bridge has timber trestles at each end, with a central span of steel broad flanged beams between concrete piers.[1]

Kuranda railway station

The line continues along the west bank of the Barron River to Kuranda Station, at 33.23 kilometres (20.65 mi). The northernmost operating station in Queensland, Kuranda Station is aligned north-west to south-east, on the north-east boundary of the town of Kuranda.[1]

Built on a raised island platform (one track southwest of Platform 1, three tracks to the northeast of Platform 2), the station consists of a number of detached buildings, the largest being the passenger station building.[1]

The Federation style station building is a single storeyed rectangular structure with a hipped gable roof. The building, centrally located on the island platform, has two cantilevered upswept awnings with bullnose leading edges, supported on steel lattice trusses, covering the adjacent platform areas. The roof has three metal Boyle's ventilators mounted along the ridge, with hipped gables protruding from the slope to either side of each ventilator. The building houses a semi-enclosed booking lobby at the northwest end, a station master's office, a waiting shed open to platforms 1 and 2, ladies toilets, a passage between platforms 1 and 2, and at the easternmost end a gift shop and cafe, with an attached kitchen in a lean-to extension.[1]

Concrete walls to window sill height support the precast concrete planking above. The passenger station building, signal cabin and utilities block are all constructed using a precast concrete system consisting of reinforced concrete planks slotted horizontally into a concrete frame, supported on concrete walls. Their timber framed roofs are clad in ribbed metal sheeting.[1]

Openings in the station building are fitted with timber framed doors and double hung windows. The ticket windows between the booking lobby and the office are of double hung casements with decorative steel grilles. A crafted timber World War I Roll of Honour commemorating Kuranda School Past Pupils is located between the ticket windows. Entrances into the booking lobby, waiting shed and passage are ornamented with timber valances which form arches. Internal finishes in the station building are generally painted concrete walls, concrete floors and timber boarded ceilings. The building is enhanced by potted palms, ferns and hanging baskets of tropical rainforest plants.[1]

Subsidiary structures located on the island platform south-east of the main station building include: a modern shade structure (not of cultural heritage significance); a signal cabin; and a utilities block containing men's toilets, accessible toilet (former lamp room) and two store rooms.[1]

The signal cabin is a small rectangular single-roomed building with a timber framed gabled hipped roof. Timber casement windows are continuous on three elevations. On the north-west elevation there is only a centrally positioned timber panelled door. The building has a suspended timber floor elevated above the platform level. Concrete walls to floor level support the concrete plank walls above. The single internal space has a painted timber ceiling and contains a McKenzie and Holland 37-lever mechanical signal frame. Significant elements of the interlocked signalling system include the signal frame and its mechanism, plus all linkages, points, points indicators and signal towers located around the station yard.[1]

The utilities block has double hung windows with concrete walls to sill height, with concrete planks above. The gabled hipped roof has a small hipped extension on the western corner over the entrance to the men's toilets.[1]

North-west of the station building is a steel-framed pedestrian overbridge and a luggage lift, both replacements for the original items, which are not of cultural heritage significance. North-west of the luggage lift is a 2005 stone cairn memorial to the building of the Kuranda Range Railway. A series of large garden beds continue along the platform to the north-west. An old steel telephone pole is located near the overbridge, on the town side. The former station master's residence is located north-west of the station platform, on the west side of the line. It is a timber building, clad in chamferboard with enclosed front and side verandahs and a hipped metal roof. A railway turntable is located further north-west.[1]

At the south-east end of the main station platform is another garden. Further south-east to the west of the line is a corrugated iron clad goods shed with a gabled roof. It stands on timber stumps, although its timber loading platform is supported on steel poles. Opposite the goods shed, east of the line, is a modern driver's quarters (not of cultural heritage significance). Further to the south-east, east of the line, are located: an old steel carriage used for storage (not of cultural heritage significance); a skillion-roofed three-bay trolley shed (pre 1982) clad in corrugated iron; plus a two-lever ground frame with attached signals and points.[1]

Four semaphore signal towers, which include kerosene lanterns with coloured lenses, are located south-east of the station platform, including one at the south-east elevation of the goods shed and a three arm tower near the trolley shed. There is another signal tower outside the station towards Cairns. There are also two semaphore towers north-west of the station, including a second three arm tower.[1]

Crooked Creek bridge

On leaving Kuranda Station, the line continues to follow the Barron River, reaching the Crooked Creek Bridge at 34.75 kilometres (21.59 mi). This consists of deck-type steel plate girders, supported on a concrete pier with later steel piers near the abutments.[1]

Modern features of no cultural heritage significance located at the railway stations and along the line between Redlynch and Crooked Creek Bridge include: modern QR buildings and sheds; bitumen access points to rails for vehicles; modern fencing; weather stations; helipads; fire fighting water tanks; solar powered telecommunication units; rock fall barriers (large stones in mesh cages and large steel-ring fences); rock anchors in high outcrops above Stoney Creek Bridge; modern footbridges over the line; and modern elements at Barron Falls Station.[1]

Heritage listing

The section from Redlynch to Crooked Creek Bridge on the Cairns railway was listed on the Queensland Heritage Register on 21 August 1992 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the evolution or pattern of Queensland's history.

The portion of the Cairns Railway between Redlynch and Crooked Creek Bridge was built 1887-91 as part of a railway to the tin-mining town of Herberton. The railway's ascent of the coastal range demonstrates the Queensland Government's policy of building railways from ports to inland mining centres to promote economic growth.[1]

The Cairns Railway is closely associated with the economic development of Cairns and the surrounding region. As a result of its selection as Herberton's port, Cairns became the largest town in Far North Queensland. Although the railway did not reach Herberton until 1910, the ascent of the range facilitated timber getting and then farming on the Atherton Tableland.[1]

The place is also closely associated with the development of tourism in Far North Queensland. From 1891 the second section of the Cairns Railway facilitated visits to Stoney Creek Falls and the Barron Falls, and Stoney Creek Station and Kuranda Station became important stops for visitors. The township of Kuranda and Kuranda Railway Station remain major tourist attractions.[1]

Redlynch Railway Station is significant as it contains early infrastructure located at the end of the first section of the Cairns Railway (built 1886-1887), and is the start of the ascent to Kuranda.[1]

The place demonstrates rare, uncommon or endangered aspects of Queensland's cultural heritage.

Kuranda Railway Station includes three early (c.1914) surviving Queensland examples of pre-cast concrete railway station buildings, and has one of the few mechanically interlocked signal cabins still commissioned in Queensland. The complex is also a rare surviving resort station, comparable with those at Spring Bluff (Main Range Railway) and Yeppoon railway station.[1]

Stoney Creek Station has a rare combination of scenic beauty and evidence of its past role as a service point for steam trains climbing the coastal range. The water tank provides rare surviving evidence of the age of steam trains in Queensland, and the sand shed is also rare.[1]

The design of the curved, steel lattice girder Stoney Creek Bridge is unique in Queensland's railways. It and Christmas Creek Bridge are also the only two Queensland railway bridges constructed with wrought iron trestles.[1]

Bridge 42 employs reused fishbelly plate cross-girders as its main span members, which is rare.[1]

Surprise Creek Bridge is one of a small group of bridges extant in Queensland with pin jointed spans.[1]

Christmas Creek Bridge is a rare example using both lattice girder and lattice truss span members.[1]

The place has potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of Queensland's history.

The sites of former camps and townships within the railway reserve between Redlynch and Crooked Creek Bridge have the archaeological potential to reveal information on the organisation and domestic life of 1880s railway camps in Queensland.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a particular class of cultural places.

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a railway range crossing, incorporating 15 tunnels, 15 steel bridges and 24 timber bridges. The line's tight curves, embankments, cuttings, culverts and drains are also characteristic of the engineering techniques needed to traverse steep, unstable terrain. The culverts and drains are vital in a tropical climate with a high rainfall.[1]

Kuranda Railway Station is an intact station complex and is an excellent example of the work of the architectural section of the Railway Department's Chief Engineer's Office under Vincent Price.[1]

The main elements of Kuranda Station which contribute to an understanding of the how the complex functioned include the concrete main station building, its platform and garden beds; the concrete male toilet block; the concrete signal cabin with its associated mechanical signal frame, linkages, semaphore signal towers, points, and points indicators; the goods shed; the trolley shed; the Station Master's residence; and the turntable.[1]

Stoney Creek Bridge has remained substantially unchanged since it was built and is an important example of large metal truss bridges, which played an important role in creating the Queensland rail transport network.[1]

The plate girder main spans of Crooked Creek Bridge are the oldest of their type still in use in Queensland, being a reuse of girders from an original 1867 bridge on the Main Range (Ipswich to Toowoomba line).[1]

The place is important because of its aesthetic significance.

The train trip through the Barron Falls National Park is a highly popular tourist attraction, due to the rugged beauty of the terrain, the many bridges and tunnels, and the views from the railway.[1]

Stoney Creek Station is a location of scenic beauty where day trippers once stopped to view Stoney Creek Falls and Stoney Creek Bridge. The latter is one of the most photographed railway bridges in Australia due to its remarkable location across a deep ravine with a waterfall backdrop. Photographs of the falls and the bridge have featured in railway advertising over many decades.[1]

Kuranda Railway Station is renowned for its dramatic setting, established gardens and showpiece station buildings. Harmoniously combined, these elements create a picturesque aesthetic effect.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating a high degree of creative or technical achievement at a particular period.

The ascent to a height of 327.7 metres (1,075 ft) at Barron Falls Station is an outstanding engineering achievement in a tropical environment, cut through unstable and rugged terrain. It demonstrates the nature of the challenge surmounted by John Robb, his workers and government engineers such as Willoughby Hannam and John Gwynneth. There were numerous deviations to the surveyed line during construction, and the railway utilises cuttings, embankments, tight curves, and multiple bridges, tunnels, culverts and drains.[1]

The place contains the largest collection of late nineteenth century tunnels and timber and metal span bridges of any other section of railway in Queensland of comparable length.[1]

Stoney Creek Bridge is a spectacular feat of civil engineering, with an 80 metres (260 ft) radius curve, mounted on wrought iron trestles, passing in front of a waterfall. It is of technical significance for its degree of complexity on a difficult site.[1]

The place has a strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

The train trip from Cairns to Kuranda, in particular the ascent past Redlynch, is a socially significant scenic railway attracting thousands of local, national and international visitors each year.[1]

Stoney Creek Bridge and its accompanying waterfall has been an attraction for tourists visiting north Queensland since the 1890s, while Kuranda Railway Station is one of Australia's most popular tourist destinations and is known worldwide.[1]

References

- "Cairns Railway, Section from Redlynch to Crooked Creek Bridge (entry 600755)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- Hudson, A. 2003. Tracks of Triumph: A tribute to the pioneers who built the famous Kuranda Scenic Railway, p. 9. Also 'Telegraphic Despatches', Rockhampton Bulletin 4 October 1876, p.2.

- 'The Herberton Railway', Brisbane Courier, 13 September 1884, p.3.

- Kerr, J.D. July 1993. Queensland Rail Heritage Report, Final Report July 1993, Part 2 Section 4.9-Index, Pages 4-153 to 9-2. p.4-293

- Brisbane Courier, 18 November 1885.

- Maconachie, G. 'Blood on the Rails: the Cairns-Kuranda Railway Construction and the Queensland Employers' Liability Act', Labour History, Number 73, November 1997. p.82; also see Hudson, p.28.

- "The Cairns Range Railway". Stratford History Trail. Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- "Advertising". Cairns Post. III (152). Queensland, Australia. 8 April 1886. p. 3. Retrieved 24 September 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- Broughton, AD. 1991. A pictorial history of the construction of the Cairns Range Railway, 1886-1891. Historical Society of Cairns, p.5.

- Hudson, p.61.

- Broughton, p.5.

- 'Cairns-Herberton Railway', Cairns Post 12 December 1888, p.2.

- Webber, B. 1997. Railway Tunnels in Queensland. Australian Railway Historical Society, Brisbane, p.6.

- Personal Communication, Wayne Harisson, QR.

- Hudson, p.109

- 'Cairns-Herberton Railway', Cairns Post, 12 December 1888, pp 2-3.

- Kerr, , Final Report July 1993, Part 2, p.4-295

- Ward, A and Milner, P. April 1997. Queensland Railway Heritage Places Study: Stage 2, Volume 8. Queensland Department of Environment and Queensland Rail, p.86.

- Much to the relief of journalists present, who were thus able to concentrate on drinking rather than writing. 'With the Governor in the North', The Queenslander, 7 June 1890, pp.1074-1075.

- Kerr, J. 1990. Triumph of the Narrow Gauge: a history of Queensland Railways. Boolarong, Brisbane, p.53.

- Hudson, p.31.

- Hudson, p.75 (regarding causes of death). Hudson counted 26 accidental deaths, including one snakebite victim. Other sources put the accidental deaths as high as 32 men, including 7 supposedly killed (unconfirmed) in a collapse of Tunnel 15 in April 1889.

- Maconachie, p.77.

- 'The Strike on the Second Section', Cairns Post, 6 September 1890, p.2

- Hudson, p.81.

- Collinson, JW. 1954. 'Building the Cairns Range Railway', Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, Volume 5 issue 3. p.1074.

- Hudson, p.93.

- 'Better Late than Never', Cairns Post 17 June 1891, p.2.

- 'The late Mr Willoughby Hannam', Cairns Post 8 March 1893, p.2.

- Kerr, Final Report July 1993, Part 2, p.4-293.

- Kerr, Triumph of the Narrow Gauge, p.53.

- Kerr, Triumph of the Narrow Gauge, pp.121-122.

- Ward and Milner, p.106.

- 'Etheridge Railway', QHR 601637.

- Gunton, C. July 1993. Kuranda Railway Station Conservation Plan. Queensland Railways. pp.4, 7.

- 'By the Way', Cairns Post 1 September 1914, p.4.

- 'Improvements at Ascot Railway Station', Brisbane Courier, 21 February 1914, p.4.

- 'Signals, Crane and Subway, Charters Towers Railway Station', QHR 602627.

- Hallam, Greg. 'The Kuranda Scenic Railway: an Historical Overview', QR heritage, p.5

- 'The Cairns Herberton Railway' Cairns Post 28 September 1887, p.3.

- Hallam, p.4.

- Hallam, p.6.

- EPA 2001. Heritage Trails of the Tropical North. Queensland Environmental Protection Agency, Brisbane, p.93.

- Hudson, p.141.

- Hudson, p. 40. Photo of Redlynch station building in 1890.

- 'Divisional Board', Cairns Post 29 August 1888, p.2.

- Ward and Milner, p.76.

- Buchanan Architects, 'Cairns to Kuranda, Section 2, Individual places', in Volume 1, Far North Queensland Lines. Report for QR, 2002, p.12.

- Tunnel lengths as given by QR staff during site visit, 20 April 2011. These vary slightly from the figures for each tunnel's length given in Webber's Railway Tunnels in Queensland.

- For more detailed descriptions of the section's steel bridges, see Ward and Milner, Queensland Railway Heritage Places Study: Stage 2, Volume 8.

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on "The Queensland heritage register" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 7 July 2014, archived on 8 October 2014). The geo-coordinates were originally computed from the "Queensland heritage register boundaries" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 5 September 2014, archived on 15 October 2014).

This Wikipedia article was originally based on "The Queensland heritage register" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 7 July 2014, archived on 8 October 2014). The geo-coordinates were originally computed from the "Queensland heritage register boundaries" published by the State of Queensland under CC-BY 3.0 AU licence (accessed on 5 September 2014, archived on 15 October 2014).

Further reading

- Kennedy, Victor, 1895-1952, The glory of Kuranda, Cairns Daily Times, retrieved 9 April 2016CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

![]() Media related to Cairns-Herberton Railway at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cairns-Herberton Railway at Wikimedia Commons

- Queensland Railways (1910), Queensland railways : train trips while steamer waits, Dept. of Railways, retrieved 9 April 2016 — digitisation available online

- Building the Kuranda railway : history in pictures John Oxley Library Blog