Cam Ranh Bay

Cam Ranh Bay (Vietnamese: Vịnh Cam Ranh) is a deep-water bay in Vietnam in Khánh Hòa Province. It is located at an inlet of the South China Sea situated on the southeastern coast of Vietnam, between Phan Rang and Nha Trang, approximately 290 kilometers (180 miles) northeast of Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon).

Cam Ranh is considered the finest deepwater shelter in Southeast Asia.[1] The continental shelf of Southeast Asia is relatively narrow at Cam Ranh Bay, bringing deep water close to land.

Since 2011-2014, Vietnamese authorities have hired Russian consultants and purchased Russian technologies to re-open Cam Ranh Bay (a former United States and later Soviet military base) as the site of a new naval maintenance and logistics facility for foreign warships.[2]

Overview

Historically, the bay has been significant from a military standpoint. The French used it as a naval base for their forces in Indochina. It was also used as a staging area for the 40-ship Imperial Russian fleet under Admiral Zinovy Rozhestvensky prior to the Battle of Tsushima in 1905,[3] and by the Japanese Imperial Navy in preparation for the invasion of British Malaya and British Borneo (today Malaysia) in 1942. In January 1945 U.S. Naval Task Force 38 destroyed most Japanese facilities in an action called Operation Gratitude,[4] after which the bay was abandoned.

In 1964, United States Seventh Fleet reconnaissance aircraft, the seaplane tender Currituck, and Mine Flotilla 1 units carried out hydrographic and beach surveys and explored sites for facilities ashore. This preparatory work proved fortuitous when a North Vietnamese trawler was discovered landing munitions and supplies at nearby Vũng Rô Bay in February 1965; the incident led the United States to develop Cam Ranh as a major base.

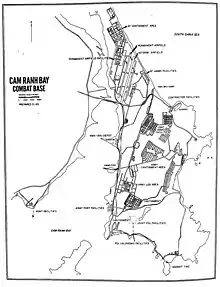

The United States Air Force operated a large cargo/airlift facility called Cam Ranh Air Base, which was also used as a tactical fighter base. It was one of three aerial ports where United States military personnel entered or departed South Vietnam for their 12-month tour of duty.

The United States Army operated a major port facility and depot at Cam Ranh. Vietnam War Handbook

The United States Navy flew various aircraft from Cam Ranh and other bases, conducting aerial surveillance of South Vietnam's coastal waters.

The APO for Cam Ranh Air Base was APO San Francisco 96326.

In May 1972, Cam Rahn facilities were turned over to the South Vietnam government.[5]

Construction

In 1963, Admiral Harry D. Felt, the U.S. Commander in Chief, Pacific (CINCPAC) foresaw that pier facilities at the natural deep-water bay at Cam Ranh might be useful in the future. At the direction of the Navy's Officer in Charge of Construction RVN (OICC RVN), the American construction consortium RMK was directed to begin construction of a 350-foot (110 m) long pier and causeway. This project was completed in mid-1964.[6]:145–6

In mid-1965, military engineers of the U.S. Army 35th Engineer Construction Group debarked at Cam Ranh Bay via LST's to set up camp and start building roads for the Cam Ranh Base. They started by establishing a quarry and then building a road leading from the quarry to the base through the desert sand using red laterite soil for a base and crushed granite rock for a topping. Once the roads were in place to carry heavy equipment, the engineers lengthened the existing pier to 600 feet (180 m) to provide an additional berth for deep-water freighters. By the end of the year, the Army engineers had added equipment storage platforms, a petrol-oil-lubricants storage area, and port cantonment and support facilities.[6]:140–2

Also in mid-1965, the American construction consortium RMK-BRJ and engineers of the Navy Officer in Charge of Construction RVN returned to construct a new airfield starting with a temporary 10,000-foot (3,000 m) runway with 2.2 million square feet (200,000 square meters) of AM-2 aluminum matting to accommodate jet fighter-bombers. By September, they had employed 1,800 Vietnamese workers for the work, over half of whom were women.[7] The Army engineers and the civilian constructors shared equipment and expertise. The runway was completed in 50 days, with Admiral U.S.G. Sharp, CINCPAC, laying the last AM-2 plank on 16 October 1965.[6]:143–6[7] A 1.3 million square feet (120,000 square meters) cargo apron using pierced steel planking, airport facilities and utilities, mess halls, and 25,000 square feet (2,300 square meters) of living quarters were also prepared for use by the U.S. Air Force.[6]:148

In 1966, four DeLong piers were added to the port.[6]:238 In January 1966, the OICC RVN tasked RMK-BRJ with construction of the Army Ammunition and Logistic Support Facility, consisting of thirty 40-foot (12 m) by 220-foot (67 m) concrete slabs for warehouses and six 140-foot (43 m) by 220-foot (67 m) slabs, 122 ammunition hardstands, and 10 miles (16 km) of roads. This work was completed by June 1966, and then RMK-BRJ turned to construction of a new 10,000-foot (3,000 m) concrete runway and taxiway at the air base.[6]:277 Later in 1966, RMK-BRJ filled in swamp land with sand at the southern end of the peninsula and constructed a naval base for Operation Market Time coastal patrols.

On 1 January 1966, the 20th and 39th Engineer Battalions and the 572nd Light Equipment Company arrived at Cam Ranh Bay to construct another pier at the port, and added a DeLong pier to the causeway at the ammunition depot.[6]:277, 353

U.S. Air Force use of Cam Ranh Bay

Army use of Cam Ranh Bay

During the Vietnam War, the U.S. Army maintained the 6th Convalescent Center (6th CC) at Cam Ranh Bay enabling most wounded soldiers to be treated in country. Only those who required advanced treatment not available in Vietnam got sent out of country. Injured and wounded soldiers whose injuries had received initial treatment, usually at an evacuation hospital unit, but who could not immediately return to duty, were sent to the 6th CC where they could recover and, if needed, receive further treatment which did not require hospitalization. The "wards" were typical wooden US Army Vietnam-type barracks. Some patients, based on the status of their injuries, were initially admitted to an Intensive Care ward. They were nothing like what one would view as an Intensive Care ward in a regular hospital. They were the normal barracks type "wards," but the patients were more closely monitored. When well enough, patients were moved to a regular ward, from which they were ultimately discharged when recovered enough to return to duty with their units.

Shortly after midnight on 7 August 1969 a Viet Cong sapper attack on the base penetrated the north perimeter and the sappers threw Satchel charges into the 6th CC killing 2 Americans and wounding 98 and damaging 19 buildings for no VC losses.[8]

The Cam Ranh Support Command was the logistical organization controlling the port and depot at Cam Ranh.[9] As of 31 July 1970, its authorized strength was 7,927, assigned 7,848.[10] The 124th Transportation Command ran the port and truck transportation units.[11] The port had 5 piers, 4 for general cargo (including one with Sea-Land cranes) and one further north for ammunition, and one jetty for a tankers.[12] Sea-Land installed its cranes on pier 4 in 1967; the first Sea-Land ship arrived in November 1967.[13] In January 1970, the port received its first containerized shipment of ammunition on Sea-Land's "Azalea City".[14] The depot was operated by the 504th Army Depot.[9] Power ships anchored in the lower harbor provided electricity to the Support Command facilities.[15]

Looking south from Harbormaster's Office, Piers 1 - 4, 4 being the Sea-Land pier, August 1969

Looking south from Harbormaster's Office, Piers 1 - 4, 4 being the Sea-Land pier, August 1969 Looking north from Harbormaster's Office, Pier 5, ammo pier, August 1969

Looking north from Harbormaster's Office, Pier 5, ammo pier, August 1969 Pier 3 and 4 in operation, September 1969

Pier 3 and 4 in operation, September 1969

Naval use of Cam Ranh Bay

.JPEG.webp)

Cam Ranh Bay became the center of coastal air patrol operations with the establishment in April 1967 of the U.S. Naval Air Facility, Cam Ranh Bay, and the basing there of P-2 Neptune and P-3 Orion patrol aircraft. That summer, the commander of the coastal surveillance force and his staff moved their headquarters from Saigon to Cam Ranh Bay and set up operational command post to control the Operation Market Time effort. Country wide coordination also was enhanced with establishment of the Naval Communications Station.

In the beginning the shore facilities at Cam Ranh Bay were extremely limited, requiring interim measures to support assigned naval forces. Army depots provided common supplies, while Seventh Fleet light cargo ships USS Mark and USS Brule (AKL-28) delivered Navy-peculiar items from Subic Bay in the Philippines. Until mid-1966 when shore installations were prepared to take over the task, messing and quartering of personnel were handled by APL-55, anchored in the harbor. Also, a pontoon dock was installed to permit the repair of the coastal patrol vessels. Gradually the Naval Support Activity, Saigon, Detachment Cam Ranh Bay, improved the provision of maintenance and repair, supply, finance, communications, transportation, postal service, recreation, and security support.

While the concentration at Cam Ranh Bay of Market Time headquarters and forces during the summer of 1967, the demand for base support became extraordinary. Accordingly, the Naval Support Activity Saigon, Detachment Cam Ranh Bay, was redesignated the Naval Support Facility, Cam Ranh Bay, a more autonomous and self-sufficient status. A greater allocation of resources and support forces to the shore installation resulted in an improved ability to cope with the buildup of combat units. In time, the Cam Ranh Bay facility accomplished major vessel repair and dispensed a greater variety of supply items to the anti-infiltration task force. In addition the naval contingent at the Joint Service Ammunition Depot issued ammunition to the coastal surveillance, river patrol and mobile riverine forces as well as to the Seventh Fleet's gunfire support destroyers and landing ships. Seabee Maintenance unit 302 provided public works assistance to the many dispersed Naval Support Activity, Saigon detachments.

As a vital logistic complex, Cam Ranh Bay continued to function long after the Navy's combat forces withdrew from South Vietnam as part of the Vietnamization of the war. However, between January and April 1972 the Naval Air Facility, and the Naval Communications Station turned over their installations to the Republic of Vietnam Navy and were duly disestablished.

Capture of Cam Ranh Bay

By the early spring of 1975 North Vietnam realized the time was right to conquer South Vietnam, so they launched a series of small ground attacks to test U.S. reaction.

With the fall of the Central Highlands and the northern provinces of South Vietnam, a general panic had set in. By 30 March, order in the city of Da Nang and in Da Nang harbor had completely broken down. Forward North Vietnamese forces fired on American vessels in Da Nang harbor and sent sappers ahead to destroy port facilities, and refugees sought to board any boat or craft afloat.

Initially, Cam Ranh Bay was chosen as the safe haven for these South Vietnamese troops and civilians transported by boat from Da Nang. But, even Cam Ranh Bay was soon in peril. Between 1 and 3 April, many of the refugees just landed at Cam Ranh reembarked for further passage south and west to Phú Quốc Island in the Gulf of Siam, and ARVN forces pulled out of the facility.

On 3 April 1975, North Vietnamese forces captured Cam Ranh Bay and all of its military facilities.

Soviet and Russian naval base

Four years after the fall of Saigon and the unification of North and South Vietnam, Cam Ranh Bay became an important Cold War naval base for the Soviet Pacific Fleet.

In 1979, the Soviet government signed an agreement with Vietnam for a 25-year lease of the base. Cam Ranh Bay was the largest Soviet naval base outside the Soviet Union, allowing it to project increased power in the East Sea. By 1987, they had expanded the base to four times its original size and often made mock attacks in the direction of the Philippines, according to intelligence of the United States Pacific Fleet. Analysts suggested that the Vietnamese side also saw the Soviet presence there as a counterweight against any potential Chinese threat. The Soviet Union and Vietnam officially denied any presence there.[16] However, as early as 1988, then-Soviet foreign minister Eduard Shevardnadze had discussed the possibility of a withdrawal from Cam Ranh Bay, and concrete naval reductions were realised by 1990.[17][18]

The Russian government continued the earlier 25-year arrangement in a 1993 agreement that allowed for the continued use of the base for signal intelligence, primarily on Chinese communications in the South China Sea. By this time, most personnel and naval vessels had been withdrawn, with only technical support for the listening station remaining. As the original 25-year lease was nearing its end, Vietnam demanded $200 million in annual rent for the continued operation of the base. Russia balked at this, and decided to withdraw all personnel. On May 2, 2002, the Russian flag was lowered for the last time. Vietnamese officials have considered turning the base into a civilian facility, similar to what the Philippines government did with the U.S.Subic Naval Base. On October 7, 2016 Russia indicated it was reconsidering its departure from naval facilities in Vietnam.[19]

Today

After the Russian withdrawal, the United States negotiated with Vietnam to open Cam Ranh Bay to calls by foreign warships, as it previously had done with the ports of Haiphong in northern Vietnam, and Ho Chi Minh City in the south. In a move that security commentators say is aimed at countering China's build-up of naval power in the South China Sea, Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung announced on October 31, 2010 that the bay would reopen to foreign navies after a three-year project to upgrade the port's facilities.[20][21] Vietnam has hired Russian consultants to direct the construction of new ship-repair facilities, which are scheduled to be available to foreign warships.[2]

The United States Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta visited Cam Ranh Bay in June 2012, the first visit by an American official of cabinet rank to Vietnam since the Vietnam War.[22]

On 2 October 2016, US Navy ships USS John S. McCain and USS Frank Cable made the first port visit to Cam Ranh Bay since 1975.[23]

Ba Ngoi Port

Ba Ngoi port is an international commercial port located within Cam Ranh Bay, which has advantageous natural conditions and potential for developing seaport services, such as: the depth of anchorage area, airtight and wide bay, nearby International Marine route (about 10 km), Cam Ranh Airport (about 25 km), National Highway No.1A (about 1.5 km) and National Railway (about 3 km). Therefore, it has been an important centre of marine traffic covering the economic zone of south Khanh Hoa and neighbouring provinces for a long time.

References

- "Cam Ranh Bay". Encyclopædia Britannica Article. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- "Vietnam's Cam Ranh base to welcome foreign navies". The Associated Press. 2010-11-02. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- Storey, Ian; Thayer, Carlyle A. (December 2002). "Cam Ranh Bay: Past Imperfect, Future Conditional". Contemporary Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. 23 (3): 452–473. doi:10.1355/CS23-3D. JSTOR 25798562. – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- "Operation GRATITUDE". mighty90.com. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- borntowander (11 November 2007). "Cam Ranh Bay: Ghost Town Part 1". Retrieved 10 April 2018 – via YouTube.

- Tregaskis, Richard (1975). Southeast Asia: Building the Bases; the History of Construction in Southeast Asia. Washington, DC: Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 952642951.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Myers, L. D.; McPartland, E. J. (March–April 1966). "Building An Interim Air Base". U.S. Navy Bureau of Yards & Docks. Navy Civil Engineer Magazine.

- Lipsman, Samuel; Doyle, Edward (1984). Fighting for Time (The Vietnam Experience). Boston Publishing Company. pp. 59-62. ISBN 9780939526079.

- The Vietnam War Handbook, Andrew Rawson, The History Press (2008), p. 155.

- Operational Report, Lessons Learned Headquarters US Army Support Command, period ending 31 July 1970, signed BG H. R. Del Mar, dated 31 July 1970 (http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/513746.pdf)

- The Vietnam War Handbook, Andrew Rawson, The History Press (2008), p. 157.

- Recollection, Stephen Knowlton, CPT, 124th Transportation Command, August 1969 - July 1970; The Vietnam War Handbook, ibid., p. 156; Senior Officer Debriefing Report, signed COL Frank Gleason, dated 28 July 1969, p. 7 (T-5 jetty upgrade in operation January 1969).

- The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger, by Marc Levinson, Princeton University Press (2016) p. 243.

- Recollection, ibid.

- The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger, p. 260; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xhkZWJKIsvk

- Trainor, Bernard E. (1987-03-01). "Russians in Vietnam: U.S. sees a threat". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

- Mydans, Seth (1988-12-23). "Soviets Hint at Leaving Cam Ranh Bay". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-01-04.

- Weisman, Steven R. (1990-06-04). "Japanese-U.S. Relations Undergoing a Redesign". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-01-04.

- "Russia 'considering military bases in Cuba and Vietnam'". BBC. London: British Broadcasting Corporation. 2016-10-07. Retrieved 2016-10-07.

- "Vietnam to reopen Cam Ranh Bay to foreign fleets: PM". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- Sharma, Amol; Page, Jeremy; Hookway, James; Pannett, Rachel (2011-02-12). "Asia's new arms race". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- https://news.yahoo.com/panetta-visit-former-us-vietnam-034326335.html (AFP via Yahoo News)

- "United States warships make first visit to Vietnam base in decades". South China Morning Post. 4 October 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

External links

- Cam Ranh Bay Photo Album

- Steve Lentz's Cam Ranh and Nha Trang Pictures 1968/1969

- Coastal bays in Vietnam and potential use. Publisher. Science & Technology. Hanoi. 295 pages

- Airport information for VVCR at World Aero Data. Data current as of October 2006.

- Media

- The short film STAFF FILM REPORT 66-1 (1966) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The short film STAFF FILM REPORT 66-10B (1966) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The short film STAFF FILM REPORT 66-21A (1966) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The short film STAFF FILM REPORT 66-28A (1966) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The short film STAFF FILM REPORT 66-29A (1966) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The short film STAFF FILM REPORT 66-30A (1966) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

Videos of Cam Rahn's development can be found at:

Ghost town