Phú Quốc

Phú Quốc (Vietnamese: [fǔ kǔə̯k]) is the largest island in Vietnam. Phú Quốc and nearby islands, along with the distant Thổ Chu Islands, are part of Kiên Giang Province as Phú Quốc City, the island has a total area of 574 km2 (222 sq mi) and a permanent population of approximately 179480.[1] Located in the Gulf of Thailand, the island city of Phú Quốc includes the island proper and 21 smaller islets. Dương Đông ward is located on the west coast, and is also the administrative and largest town on the island. The other ward is An Thới on the southern tip of the island.

Phú Quốc

Thành phố Phú Quốc | |

|---|---|

| Phú Quốc City | |

Phu Quoc island | |

Seal | |

Phú Quốc | |

Phú Quốc Phú Quốc | |

| Coordinates: VN 10°14′N 103°57′E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Kiên Giang |

| Area | |

| • Total | 589.27 km2 (227.52 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 179,480 |

| • Density | 305/km2 (790/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+7 (ICT) |

| Calling code | 855 |

| Website | phuquoc |

.jpg.webp)

Its primary industries are fishing, agriculture, and a fast-growing tourism sector. Phú Quốc has achieved fast economic growth due to its current tourism boom. Many infrastructure projects have been carried out, including several five-star hotels and resorts. Phú Quốc International Airport is the hub connecting Phú Quốc with mainland Vietnam and other international destinations.

From March 2014, Vietnam allowed all foreign tourists to visit Phú Quốc visa-free for a period of up to 30 days.[2][3] By 2017, the government of Vietnam planned to set up a Special Administrative Region which covered Phú Quốc Island and peripheral islets and upgrade it to a provincial city with special administration.

The historical Phú Quốc Prison was based here; the prison was built by French colonialists to detain captured Viet Cong and North Vietnamese soldiers.

Geography

Phú Quốc lies south of the Cambodian coast, south of Kampot, and 40 km (25 mi) west of Hà Tiên, the nearest coastal town in Vietnam. Roughly triangular in shape the island is 50 kilometres (31 mi) long from north to south and 25 kilometres (16 mi) from east to west at its widest. It is also located 17 nautical miles from Krong Kampot, 62 nautical miles (115 km; 71 mi) from Rạch Giá and nearly 290 nautical miles (540 km; 330 mi) from Laem Chabang, Thailand. A mountainous ridge known as "99 Peaks" runs the length of Phú Quốc, with Chúa Mountain being the tallest at 603 metres (1,978 ft).

Phú Quốc Island is mainly composed of sedimentary rocks from the Mesozoic and Cenozoic age, including heterogeneous conglomerate composition, layering thick, quartz pebbles, silica, limestone, rhyolite and felsite. The Mesozoic rocks are classified in Phú Quốc Formation (K pq). The Cenozoic sediments are classified in formations of Long Toàn (middle - upper Pleistocene), Long Mỹ (upper Pleistocene), Hậu Giang (lower - middle Holocene), upper Holocene sediments, and undivided Quaternary (Q).[4]

Administrative units

The city of Phu Quoc is officially divided into nine district-level sub-divisions, including two urban districts (Dương Đông, An Thới) and seven rural districts (Bãi Thơm, Cửa Cạn, Cửa Dương, Dương Tơ, Gành Dầu, Hàm Ninh, Thổ Châu).

Economy

Phú Quốc is famous for its two traditional products: fish sauce and black pepper. The rich fishing grounds offshore provides the anchovy catch from which the prized sauce is made. As widely agreed among the Vietnamese people, the best fish sauce comes from Phú Quốc. The island name is very coveted and abused in the fish sauce industry that local producers have been fighting for the protection of its appellation of origin.[5] Pepper is cultivated everywhere on the island, especially at Gành Dầu and Cửa Dương communes.[6] The pearl farming activity began more than 20 years ago when Australian and Japanese experts arrived to develop the industry with advanced technology. Some Vietnamese pearl farms were established at that time including Quốc An.[7]

Tourism plays an important role in the economy, with the beaches being the main attraction. Phú Quốc was served by Phú Quốc Airport with air links to Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) Tan Son Nhat International Airport, Hanoi (Noi Bai International Airport), Rạch Giá (Rạch Giá Airport) and Can Tho (Can Tho International Airport). Phú Quốc Airport was closed and replaced by the new Phú Quốc International Airport from December 2, 2012.[8] Phú Quốc is also linked with Rạch Giá and Hà Tiên by fast ferry hydrofoils.

Air Mekong used to have its headquarters in An Thới.[9][10]

Many domestic and international projects related to tourism have been carried out, including the latest direct flights from Bangkok to Phú Quốc by Bangkok Airways, which could make Phú Quốc a new tourist hub in Southeast Asia.

With the combination of Vinpearl Phú Quốc Resorts and the opening of the new Vinmec Phú Quốc International Hospital in June 2015, Phú Quốc will add an additional source of revenue to the local economy in terms of medical services, medical tourism, and medical education.[11]

History

The earliest Cambodian references to Phú Quốc (Koh Tral) are found in royal documents dated 1615, reflecting the allocation of the various governors’ authorities among the territories of the Khmer empire. [12]

Around 1680, one of Cambodian kings granted Chinese merchant and explorer Mạc Cửu the authority to settle and develop a large swath of unproductive Cambodian coast, a project that resulted in his establishing Hà Tiên and six other villages as trading centers, including one village on Phu Quoc.

Mạc Cửu later switched allegiance to the Nguyễn lords and recognized the authority of the Vietnamese sovereign.[12][13] He sent a tribute mission to the Nguyễn court in 1708, and in return received the title of Tong Binh of Hà Tiên[14] and the noble title Marquess Cửu Ngọc (Vietnamese: Cửu Ngọc hầu)

Mạc Cửu died in 1736, his son Mạc Thiên Tứ (Mo Shilin) succeeded. A Cambodian army invaded Hà Tiên in 1739 but was utterly defeated. From then on, Cambodia did not try to resume Hà Tiên, Hà Tiên enjoyed full independence from Cambodia thereafter.[15]

Mạc Thiên Tứ's reign saw the golden age of Hà Tiên. In 1758, Hà Tiên established Outey II as puppet king of Cambodia. After War of the second fall of Ayutthaya, Mạc Thiên Tứ tried to install Prince Chao Chui (เจ้าจุ้ย, Chiêu Thúy in Vietnamese) as the new Siamese king, but was defeated by Taksin.[16] Hà Tiên was completely devastated by Siamese troops in 1771, Mạc Thiên Tứ had flee to Trấn Giang (modern Cần Thơ). In there, he was sheltered by Nguyễn lord. Two years later, Siamese army withdrew from Hà Tiên, and Mạc Thiên Tứ retook his principality.[16]

The French missionary Pigneau de Behaine used the island as a base during the 1760s and 1780s to shelter Nguyễn Ánh, who was hunted by the Tây Sơn army.[17] Descriptions of this mission make reference to the local Vietnamese population of the island but not the Khmer.[12]

An 1810 description of the coastal route from Vietnam to Thailand prepared by court officials to Gia Long describes Phu Quoc as having a local (Vietnamese) administrative office and military officers, with a dense population devoted to a range of economic activities.[12]

The British envoy John Crawfurd en route to Siam from Singapore in 1822 made a stop at Phú Quốc which he transcribed as Phu-kok in March. His entry is as follows:

The place which we had now visited is called by the Cochinchinese, Phu-kok, and by the Siamese Koh-dud... In the Kambojan language it is called Koh-trol... It is the largest island on the east coast of the Gulf of Siam, being by our reckoning not less than thirty-four miles in length. It is commonly bold high land, the highest hills rising to seven or eight hundred feet. A few spots here and there on the coasts only are inhabited, -the rest being, as usual, covered with a great forest, which we were told, contained abundance of deer, hogs, wild buffaloes, and oxen, but no leopards or tigers... The inhabitants of Phu-kok were described to us as amounting to four to five thousand, all of the true Cochinchinese race, with the exception of a few occasional Chinese sojourners. They grow no species of corn and their husbandry is confined to a few coarse fruits and esculent green vegetables and farinaceous roots..."[18]

Western record in 1856 again mentioned the island: "... King Ang Duong (of Cambodia) apprise Mr. de Montigny, French envoy in visit to Bangkok, through the intermediary of Bishop Miche, his intention to yield Phu Quoc to France."[19] Such a proposition aimed to create a military alliance with France to avoid the threat of Vietnam on Cambodia. The proposal did not receive an answer from the French.[20] An 1856 publication by The Nautical Magazine describes Phu Quoc to still be part of Cambodia even though it was occupied by the Cochinchinese. The quote from the publication is:

The whole of the island is thickly wooded, and only the shore parts appear to be inhabited, principally by Cochinchinese, for although in the empire of Cambodia it has been seized upon by the unscrupulous inhabitants of Cancao."[21]

While the war between Vietnam and France was about to begin, Ang Duong sent another letter, dated November 25, 1856, to Napoleon III to warn him on Cambodian claims on the lower Cochinchina region: the Cambodian king listed provinces and islands, including Phú Quốc, as being parts of Vietnam for several years or decades (in the case of Saigon some 200 years). Ang Duong asked the French emperor to not annex any part of these territories because, as he wrote, despite this relatively long Vietnamese rule, they remained Cambodian lands. In 1867, Phú Quốc's Vietnamese authorities pledged allegiance to French troops just conquering Hà Tiên.

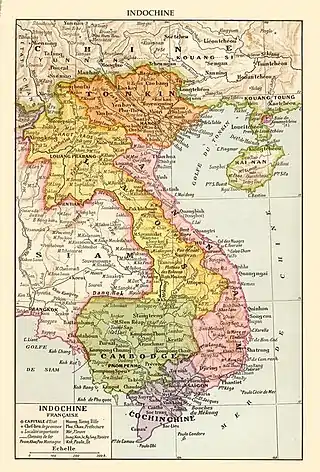

In 1939, Governor General of French Indochina, Jules Brévié, sent a letter to the Governor of Cochinchina about “the issue of the islands in the Gulf of Siam whose is a matter of controversy between Cambodia and Cochin-China”. In this letter,“for administrative purposes”, he drew a line which defined the border between the waters of Cambodia and Cochin-China: all the islands north of the line are under Cambodian sovereignty, all the islands south of the line are ruled by Cochin-China. [22] As a result, Phú Quốc remained under Cochinchina administration. In 1949, Cochin-China became part of Vietnam, an Associated State in the French Union within the Indochinese Federation. After the Geneva Accords, in 1954, Cochinchina's sovereignty was handed over to Vietnam.

After Mainland China fell under the control of the Chinese Communist Party in 1949, General Huang Chieh moved 33,000+ Republic of China Army soldiers mostly from Hunan Province to Vietnam and they were interned on Phú Quốc. Later, the army moved to Taiwan in June 1953.[23]

In 1964, then Head of State Prince Norodom Sihanouk proposed to the Vietnamese a map aimed at settling the issue. Cambodia offered to accept the colonial “Brévié Line” as the maritime boundary, thus abandoning its claim to Koh Trâl. That position of Cambodia was confirmed by maps given to the mission sent by the UN Security Council after the Chantrea incidents. On June 8, 1967, the Vietnamese issued a declaration that accepted the “Brévié Line” as the maritime border.

In 1969 Sihanouk renewed his claim on Koh Tral as did the Lon Nol administration which followed. The Vietnamese hardened their position and backed off their previous acceptance of the Brevie Line seeking more generous sea lanes around the islands.[12]

From 1953 to 1975, the island housed South Vietnam's largest prisoner camp (40,000 in 1973), known as Phú Quốc Prison.[24]

On May 1, 1975, a squad of Khmer Rouge soldiers raided and took Phú Quốc, but Vietnam soon recaptured it. This was to be the first of a series of incursions and counter-incursions that would escalate to the Cambodian–Vietnamese War in 1979. Cambodia dropped its claims to Phú Quốc in 1976.[25] But the bone of contention involving the island between the governments of the two countries continued, as both have a historical claim to it and the surrounding waters. A July 1982 agreement between Vietnam and The People's Republic of Kampuchea ostensibly settled the dispute; however, the island is still the object of irredentist sentiments.[26]

in 1999 the Cambodian representative to the Vietnam-Cambodia Joint Border Commission affirmed the state’s acceptance of the Brevie Line and Vietnamese sovereignty over Phu Quoc, a position reported to and accepted by the National Assembly.[12]

Climate

The island's monsoonal sub-equatorial climate is characterized by distinct rainy (April to November) and dry seasons (December to March). As is common in regions with this climate type, there is some rain even in the dry season. The annual rainfall is high, averaging 3,029 mm (9.938 ft). In the northern mountains up to 4,000 mm (13 ft) has been recorded. April and May are the hottest months, with temperatures reaching 35 °C (95 °F).

| Climate data for Duong Dong Airport, Phu Quoc | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 35.1 (95.2) |

35.3 (95.5) |

38.1 (100.6) |

37.5 (99.5) |

37.0 (98.6) |

33.7 (92.7) |

33.3 (91.9) |

33.4 (92.1) |

33.3 (91.9) |

34.5 (94.1) |

33.2 (91.8) |

34.6 (94.3) |

38.1 (100.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.4 (86.7) |

31.1 (88.0) |

32.1 (89.8) |

32.3 (90.1) |

31.4 (88.5) |

30.0 (86.0) |

29.5 (85.1) |

29.2 (84.6) |

29.2 (84.6) |

29.9 (85.8) |

30.3 (86.5) |

30.0 (86.0) |

30.5 (86.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 25.6 (78.1) |

26.5 (79.7) |

27.6 (81.7) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.4 (83.1) |

27.8 (82.0) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.0 (80.6) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.0 (78.8) |

27.1 (80.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 22.5 (72.5) |

23.5 (74.3) |

24.6 (76.3) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.0 (75.2) |

22.9 (73.2) |

24.4 (75.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 16.0 (60.8) |

16.0 (60.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

21.0 (69.8) |

22.1 (71.8) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

22.0 (71.6) |

20.8 (69.4) |

16.0 (60.8) |

17.1 (62.8) |

16.0 (60.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 34 (1.3) |

29 (1.1) |

54 (2.1) |

149 (5.9) |

298 (11.7) |

413 (16.3) |

418 (16.5) |

546 (21.5) |

473 (18.6) |

387 (15.2) |

169 (6.7) |

59 (2.3) |

3,029 (119.3) |

| Average precipitation days | 5.3 | 3.9 | 5.7 | 11.5 | 19.5 | 21.8 | 22.5 | 24.4 | 22.5 | 21.6 | 13.3 | 6.2 | 178.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76.3 | 77.6 | 77.6 | 80.5 | 83.8 | 85.8 | 86.6 | 87.1 | 88.0 | 86.9 | 79.6 | 73.9 | 82.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 251 | 230 | 255 | 246 | 196 | 146 | 151 | 134 | 139 | 168 | 208 | 242 | 2,364 |

| Source: Vietnam Institute for Building Science and Technology[27] | |||||||||||||

Protections

Phú Quốc has both a terrestrial national park and a marine protection.

Phú Quốc National Park was established in 2001 as an upgrade of a former conservation zone. The park covers 336.57 km2 (129.95 sq mi) of the northern part of the island.[28][29]

Phú Quốc Marine Protected Area, or just Phú Quốc MPA, was established in 2007 at the northern and southern end of the island and covers 187 km2 (72 sq mi) of marine area. The sea around Phú Quốc is one of the richest fishing grounds in all of Vietnam, and the aim of the protected area is to secure coral reef zones, seagrass beds, and mangrove forests, all key spawning and nursery grounds for aquatic species, including blue swimming crabs. Among the aquatic animals in the protected area are green turtle, leather back turtles, dolphin and dugong.[30][31]

Plastic waste is a growing problem in Phú Quốc, and the local community has organised clean-up efforts.[32]

Gallery

Suối Tranh Cascades

Suối Tranh Cascades Phú Quốc's sandy beaches

Phú Quốc's sandy beaches Fishermen's village

Fishermen's village Bãi Sao beach

Bãi Sao beach Shellfish for sale by the roadside

Shellfish for sale by the roadside Phú Quốc coastline

Phú Quốc coastline Phú Quốc coastline

Phú Quốc coastline Fishing boat with its collection of basket boats (thuyền thúng)

Fishing boat with its collection of basket boats (thuyền thúng) Manufacture of fish sauce

Manufacture of fish sauce A beach in Phú Quốc

A beach in Phú Quốc A bridge on Dương Đông river

A bridge on Dương Đông river Dương Đông river's mouth

Dương Đông river's mouth Hotel in Phú Quốc

Hotel in Phú Quốc Hotel in Phú Quốc

Hotel in Phú Quốc Dương Đông market

Dương Đông market Fish stalls at Dương Đông market

Fish stalls at Dương Đông market Sùng Hưng pagoda

Sùng Hưng pagoda.jpg.webp) Bãi Sao beach

Bãi Sao beach Dương Đông river

Dương Đông river Nguyễn Trung Trực's temple

Nguyễn Trung Trực's temple

See also

References

- "Phú Quốc chính thức là thành phố đảo đầu tiên của Việt Nam". December 9, 2020.

- "Visa no longer needed to enter Phu Quoc by sea". Archived from the original on 2014-05-12. Retrieved 2014-05-09.

- vietnamnet.vn. "Phu Quoc giving free 30-day visas - News VietNamNet".

- "Biển đảo Việt Nam - Tài nguyên vị thế và những kỳ quan địa chất, sinh thái tiêu biểu (Vietnamese sea and islands – position resources, and typical geological and ecological wonders)".

- Wan, Julie (21 April 2010). "The best of Vietnamese fish sauce comes from Phu Quoc". Washington Post. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- "Pepper cultivation area halved on Phu Quoc - Pepper cultivation area halved on Phu Quoc - News from Saigon Times". The Saigon Times. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Tran, Ngoc. "Pearl farming on Phu Quoc Island - Pearl farming on Phu Quoc Island - News from Saigon Times". The Saigon Times. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- "Vietnam Airlines capitalises on new Phu Quoc airport". Voice of Vietnam. 2012-12-03. Retrieved 2012-12-03.

- "About Us." Air Mekong. Retrieved on December 21, 2010. "Headquarters: Hamlet 3, Village 7, An Thoi Town, Phu Quoc Island, Kiên Giang Province, Vietnam..."

- "Website usage terms and conditions Archived 2011-09-03 at the Wayback Machine." Air Mekong. Retrieved on December 21, 2010

- "Phu Quoc Island Vietnam Official Travel Guide - 2017 - 2018".

- "Cambodia's Impossible Dream: Koh Tral". The Diplomat. June 17, 2014.

- Coedes, George (1966), The making of South East Asia, University of California Press, p. 213, ISBN 978-0-520-05061-7

- Cooke, Nola; Li, Tana (2004), Water frontier: commerce and the Chinese in the Lower Mekong Region, 1750-1880, Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 43–44, ISBN 978-0-7425-3083-6

- Cooke, Nola; Li, Tana (2004), Water frontier: commerce and the Chinese in the Lower Mekong Region, 1750-1880, Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 43–46, ISBN 978-0-7425-3083-6

- Dai, Kelai; Yang, Baoyun (1991), Ling nan zhi guai deng shi liao san zhong (in Chinese), Zhengzhou: Zhongzhou gu ji chu ban she, pp. 313–319, ISBN 7534802032

- Nick Ray, Wendy Yanagihara. Vietnam. Retrieved 2015-10-09. p.445

- Crawfurd, John. Journal of an Embassy to the Courts of Siam and Cochinchina. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1967. p64-5

- "Le Second Empire en Indo-Chine (Siam-Cambodge-Annam): l'ouverture de Siam au commerce et la convention du Cambodge”, Charles Meyniard, 1891, Bibliothèque générale de géographie

- "La Politique coloniale de la France au début du second Empire (Indo-Chine, 1852-1858)", Henri Cordier, 1911, Ed. E.J. Brill

- Remarks on the East Side of the Gulf of Siam. (1856). In The Nautical Magazine: A Journal of Papers on Subjects Connected with Maritime Affairs (p. 693). Brown, Son and Ferguson. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Nautical_Magazine/aoQEAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=koh+tron+cambodian+empire&pg=PA693&printsec=frontcover

- Polomka, Peter. Ocean Politics in Southeast Asia. Retrieved 2015-10-09. p.20

- 2009年03月31日, 抗日名将黄杰与最后一支离开大陆的国民党部队, 凤凰资讯. There is currently a small island in Kaohsiung, Taiwan's Chengcing Lake that was constructed in November 1955 and named Phu Quoc Island in memory of the Nationalist Chinese loyal soldiers who was detained from 1949-1953.

- Ngo Cong Duc, deputy of the Vinh Binh province, quoted in "Le régime de Nguyen Van Thieu à travers l'épreuve", Etude Vietnamienne, 1974, pp. 99–131

- Hanns Jürgen Buchholz. Law of the Sea Zones in the Pacific Ocean. Retrieved 2015-10-09. p.41

- Amer, Ramses. 2002. Claims and Conflict Situations in "War or Peace in the South China Sea?" edited by Timo Kivimaki. Nordic Institute of Asian Studies (NIAS), Copenhagen, Denmark

- "Vietnam Building Code Natural Physical & Climatic Data for Construction" (PDF) (in Vietnamese). Vietnam Institute for Building Science and Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- National parks

- Phu Quoc National Park

- Phu Quoc in Viet Nam

- Vietnam Marine Protected Area Management Effectiveness Evaluation (2015)

- Community cleanup efforts and local government commitment underway to tackle the mounting plastic waste issue on Phu Quoc Island

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Phu Quoc. |