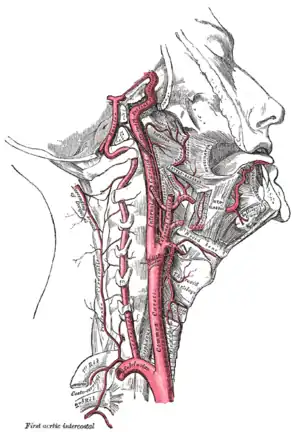

Carotid endarterectomy

Carotid endarterectomy (CEA) is a surgical procedure used to reduce the risk of stroke from carotid artery stenosis (narrowing the internal carotid artery).

| Carotid endarterectomy | |

|---|---|

Carotid endarterectomy specimen. The specimen is removed from within the lumen of the common carotid artery (bottom), and the internal carotid artery (left) and external carotid artery (right). | |

| ICD-9-CM | 38.1 |

| MeSH | D016894 |

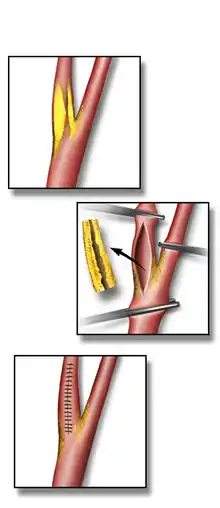

In endarterectomy, the surgeon opens the artery and removes the plaque. The plaque forms and enlarges in the inner layer of the artery, or endothelium, hence the name of the procedure which simply means removal of the endothelium of the artery.

An alternative procedure is carotid stenting, which can also reduce the risk of stroke for some patients.

Medical uses

Carotid endarterectomy is used to reduce the risk of strokes caused by carotid artery stenosis over time. Carotid stenosis can either have symptoms (ie, be symptomatic), or be found by a doctor in the absence symptoms (asymptomatic) - and the risk-reduction from endarterectomy is greater for symptomatic than asymptomatic patients.

Carotid endartectomy itself can cause strokes, so to be of benefit in preventing strokes over time, the risks for combined 30-day mortality and stroke risk following surgery should be < 3% for asymptomatic people and ≤ 6% for symptomatic people.[1]

Symptomatic

Symptomatic people have had either a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke.

In symptomatic patients with a 70–99% stenosis, for every six people treated, one major stroke would be prevented at two years (i.e. a number needed to treat (NNT) of six).[2]

Unlike asymptomatic patients, symptomatic people with mild carotid stenosis (50–69%) still benefit from endarterectomy, albeit to a lesser degree, with a NNT of 22 at five years. In addition, co-morbidity adversely affects the outcome: people with multiple medical problems have a higher post-operative mortality rate and hence benefit less from the procedure. For maximum benefit people should be operated on soon after a TIA or stroke, preferably within the first 2 weeks.[2]

Asymptomatic

Asymptomatic people have narrowing of their carotid arteries, but have not experienced a TIA or stroke. The annual risk of stroke in patients with asymptomatic carotid disease is between 1% and 2%, although some patients are considered to be at higher risk, such as those with ulcerated plaques. This low rate of stroke means that there is less potential stroke risk-reduction from endarterectomy for asymptomatic patients relative to symptomatic patients. However, carotid endarterectomy plus treatment with a statin medicine and anti-platelet therapy does reduces stroke risk further than medication alone in the five years following surgery for asymptomatic patients with severe carotid stenosis (80-99%).[3]

Complications

The most feared complication of carotid endarterectomy is stroke. Risks of stroke at the time of surgery are higher for symptomatic (3-5%) than asymptomatic patients (1-3%).[4]

Bleeding, infection, and cranial nerve injury are also risks at the time of surgery. Following surgery, a rare early complication is cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome, also known as reperfusion syndrome, which is associated with headache and high blood pressure following surgery.

Long term complications include restenosis of the endarterectomy bed, although the clinical significance of this is controversial in asymptomatic patients.

Reasons to avoid

The procedure should be avoided when:

- There is complete internal carotid artery occlusion

- The person has a previous complete hemispheric stroke on the ipsilateral and complete cerebrovascular territory side severe neurologic deficits (NIHSS>15), because there is no brain tissue at risk for further stroke damage.

- People deemed unfit for the operation by the surgeon or anesthesiologist due to comorbidities.

High risk criteria for CEA include the following:

- Age ≥80 years.

- Class III/IV congestive heart failure.

- Class III/IV angina pectoris.

- Left main or multi vessel coronary artery disease.

- Need for open heart surgery within 30 days.

- Left ventricular ejection fraction of ≤30%.

- Recent (≤30-day) heart attack.

- Severe lung disease or COPD.

- Severe renal disease.

- High cervical (C2) or intrathoracic lesion.

- Prior radical neck surgery or radiation therapy.

- Contralateral carotid artery occlusion.

- Prior ipsilateral CEA.

- Contralateral laryngeal nerve injury.

- Tracheostoma.

Carotid artery stenting is an alternative to carotid endarterectomy in cases where endarterectomy is considered too risky.

Procedure

An incision is made on the midline side of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The incision is between 5 and 10 cm in length. The internal, common and external carotid arteries are carefully identified, controlled with vessel loops, and clamped. The lumen of the internal carotid artery is opened, and the atheromatous plaque substance removed. The artery is closed using suture and a patch to increase the size of the lumen. Hemostasis is achieved, and the overlying layers closed with suture. The skin can be closed with suture which may be visible or invisible (absorbable). Many surgeons place a temporary shunt to ensure blood supply to the brain during the procedure. The procedure may be performed under general or local anaesthesia. The latter allows for direct monitoring of neurological status by intra-operative verbal contact and testing of grip strength. With general anaesthesia, indirect methods of assessing cerebral perfusion must be used, such as electroencephalography (EEG), transcranial doppler analysis, carotid artery stump pressure monitoring, or routine shunt use. At present there is no good evidence to show any major difference in outcome between local and general anaesthesia, nor between methods of determining the need for a shunt.[2]

History

The endarterectomy procedure was developed and first done by the Portuguese surgeon Joao Cid dos Santos in 1946, when he operated an occluded superficial femoral artery, at the University of Lisbon. In 1951 an Argentinian surgeon repaired a carotid artery occlusion using a bypass procedure. The first endarterectomy was successfully performed by Michael DeBakey around 1953, at the Methodist Hospital in Houston, TX, although the technique was not reported in the medical literature until 1975.[5] The first case to be recorded in the medical literature was in The Lancet in 1954;[5][6] the surgeon was Felix Eastcott, a consultant surgeon and deputy director of the surgical unit at St Mary's Hospital, London, UK.[7] Eastcott's procedure was not strictly an endarterectomy as we now understand it; he excised the diseased part of the artery and then resutured the healthy ends together. Since then, evidence for its effectiveness in different patient groups has accumulated. In 2003 nearly 140,000 carotid endarterectomies were performed in the USA.

References

- White CJ, Beckman JA, Cambria RP, Comerota AJ, Gray WA, Hobson RW, Iyer SS (2008). "Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease Symposium II: controversies in carotid artery revascularization". Circulation. 118 (25): 2852–2859. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.108.191175. PMID 19106407.

- Rerkasem, Amaraporn; Orrapin, Saritphat; Howard, Dominic Pj; Rerkasem, Kittipan (12 September 2020). "Carotid endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9: CD001081. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001081.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 32918282.

- Moresoli, P; Habib, B; Reynier, P; Secrest, MH; Eisenberg, MJ; Filion, KB (August 2017). "Carotid Stenting Versus Endarterectomy for Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Stroke. 48 (8): 2150–2157. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.016824. PMID 28679848.

- Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, et al. (2011). "ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS Guideline on the Management of Patients With Extracranial Carotid and Vertebral Artery Disease: Executive Summary A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American Stroke Association, American Association of Neuroscience Nurses, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, American College of Radiology, American Society of Neuroradiology, Congress of Neurological Surgeons, Society of Atherosclerosis Imaging and Prevention, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery, Society for Vascular Medicine, and Society for Vascular Surgery Developed in Collaboration With the American Academy of Neurology and Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography". J Am Coll Cardiol. 57 (8): 1002–44. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.005. PMID 21288680.

- Friedman, SG (December 2014). "The first carotid endarterectomy". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 60 (6): 1703–8.e1–4. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2014.08.059. PMID 25238726.

- Eastcott, HH; Pickering, GW; Rob, CG (13 November 1954). "Reconstruction of internal carotid artery in a patient with intermittent attacks of hemiplegia". Lancet. 267 (6846): 994–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(54)90544-9. PMID 13213095.

- "Felix Eastcott, arterial surgeon". The Times. London. 2009-12-31.