Cascades Park (Tallahassee)

Cascades Park is a 24-acre (97,000 m2) park along the stream known as the St. Augustine Branch in Tallahassee, Florida, south of the Florida State Capitol.[2][3] It is a Nationally Registered Historic Place because it influenced the territorial government's choice of the capital city's location.[3][4] It also contains Florida's Prime meridian marker monument which is the foundation point for most land mapping throughout Florida.[4]

Cascades Park | |

New park in 2015 | |

| |

| Location | Tallahassee, Florida |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 30°26′8″N 84°16′38″W |

| NRHP reference No. | 71000239 |

| Added to NRHP | 12 May 1971[1] |

The park as conceived in 1971 had a stream and shallow waterfalls but it closed because of soil contamination and toxic waste left buried by the gasification plant that once occupied the site.[2] It was cleaned up with Department of Environmental Protection funding in 2006 and construction on the new park was initiated in 2010 using money from the penny sales tax. The newly designed Cascades Park opened in 2014.[2] Features of the new park include the Capital City Amphitheater, a fountain with light, music, splash pads, and ponds, and boulder climbing, beachscape and outdoor classroom area known as Discovery at Cascade Park that was privately funded.[2]

History

In 1821, Spain ceded Florida to the United States. A territorial government was established, but the two largest cities, Pensacola and St. Augustine, were too far west and east, respectively, for either to make a good permanent capital. Territorial governor William Pope Duval appointed two commissioners, one from Pensacola and one from St. Augustine, to choose a location roughly halfway between them to build the new capital. When they saw a beautiful waterfall in what is now Cascades Park, they chose a nearby hill as the location for the future city of Tallahassee.[3]

John Lee Williams, the commissioner from Pensacola, wrote of the waterfall:

Doct. Simmons has agreed that the site should be fixed near the old fields abandoned by the Indians after Jackson's invasion, but has not yet determined whether between the ... old fields, or on a fine high lawn about a mile W. In both spots, the water is plenty and good ... Directly east of the old fields runs a ... stream of water which you must recollect. This stream, after running about a mile south, pitches about 20 or 30 feet (9.1 m) into an immense chasm, in which it runs 60 or 70 rods to the base of a high hill which it enters among clefts of Amorphous argilaceous ... rocks full of shells and other fossils.

— John Lee Williams[5]

The Florida State Capitol stands approximately a quarter mile northwest of where the waterfall and sinkhole were located. The area was used as a meeting place in the earlier portion of the 19th century for hunters and travelers. During the early 20th century, it was home to Centennial Field, formerly used to play minor league baseball and football, as well as a Korean War memorial. In 1971, Governor Reubin Askew and the Florida Cabinet recognized the park's significance in a resolution.

Contamination

The city operated a manufactured gas plant in the southwest of the park from 1895 to the late 1950s, when they switched to natural gas and propane.[6] As part of its normal operation, the MGP produced coal tar which was not valuable enough to be sold or reused, so it was simply discarded.[7] Potentially harmful components of this coal tar, in particular polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and BTEX (benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes), have been detected in the soil and groundwater.[6] A downward hydraulic gradient prevented the contaminants from spreading, but at the site itself, there was "a current or potential threat to public health and the environment".[6]

In addition, a landfill on the southern edge of the park was used to dispose of municipal solid waste.[8] The landfill was originally intended for biodegradable lawn waste such as tree limbs, but later it was reportedly used for other trash including construction and automobile waste and ash from the city incinerator on the east side of the park.[6]

Remediation project

In September 2005, the city made an agreement with WRS Infrastructure & Environment to clean up the site for $7.8 million.[9] The plan was to excavate over 70,000 tons of contaminated soil and transport it to an EPA-approved landfill in Valdosta, Georgia, to remove three inches (76 mm) of sediment from 950 feet (290 m) of the stream and install a protective liner, and to place a clay cap over 5,750 square yards of the landfill.[7][10]

The project was completed in 2014. The park now includes an outdoor amphitheater, biking and walking trails, and historical monuments. A privately funded children's play area contains an outdoor classroom. Other features of the park are an interactive fountain, a waterfall, and several ponds, masking the park's other function, to serve as drainage for storm water, intended to reduce local flooding.[11]

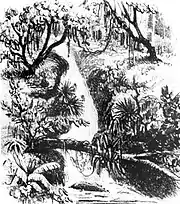

Postcard of Cascades Park (1912)

Postcard of Cascades Park (1912) Remediation in progress May 2006

Remediation in progress May 2006 Remediation completed 2014

Remediation completed 2014 Capital City Amphitheater May 2015

Capital City Amphitheater May 2015

See also

References

- "National Register Information System – Cascades Park (#71000239)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 9 July 2010.

- Dixon, Wendy (June 2014). "Tickle-down effect; City leaders call Tallahassee's Cascades Park a game-changer". Florida Trend.

- Castille, Colleen M. (Secretary FDEP) (11 Feb 2005). "State Deeds Downtown Tallahassee Park to City". The Post. 5 (6). Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP). Archived from the original on 12 Apr 2005. Retrieved 25 Aug 2006.

- Evans, Mary K.; Nimnicht, Randy F. (12 May 1971). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: or Registration:". National Park Service. with 1 photo from 1951

- Hauserman, Julie (2004). "Florida's Lost Waterfall: Cascades Park" (PDF). Between Two Rivers: Stories from the Red Hills to the Gulf. pp. 157–9. ISBN 0-9759339-0-6. Retrieved 25 Aug 2006.

- "Cascade Park Gasification Plant/Cascade Landfill Removal Action Memorandum" (PDF). Superfund Proposed Plan Fact Sheet. Evironmental Protection Agency (EPA). March 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 Jun 2003. Retrieved 25 Aug 2006.

- "Frequently Asked Questions" (PDF). Cascades Park Remediation Project. City of Tallahassee. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 Nov 2006. Retrieved 25 Aug 2006.

- "Sites in Reuse: Cascade Park Gasification Plant Superfund Site" (PDF). EPA Region 4 Site Reuse Fact Sheets. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). December 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 Nov 2006. Retrieved 25 Aug 2006.

- Bono, M. Michelle (Asst. to the City Manager) (26 September 2005). "City Reaches Agreement on Cascades Park Cleanup" (Press release). City of Tallahassee. Archived from the original on 7 Feb 2006. Retrieved 25 Aug 2006.

- "Cascades Park Clean Up: Get The Facts" (PDF). City of Tallahassee, WRS Infrastructure & Environment. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 Feb 2006. Retrieved 25 Aug 2006.

- Dixon, Wendy (28 May 2014). "Tallahassee's Cascades Park finally opens". Florida Trend. Retrieved 9 Feb 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cascades Park (Tallahassee). |

- "Florida's Office of Cultural and Historical Programs"

- "Leon County listings". Archived from the original on 11 Aug 2006

- "Cascade Park Development Site". Archived from the original on 27 Feb 2013

- The History of the Tallahassee Cascades. OCLC 43839659

- "Capital Cascades Park stormwater management and flood mitigation efforts". Archived from the original on 22 Feb 2014

- "National study for The Nature Conservancy features Capital Cascades Trail as model for urban greening"