Cathelicidin

Cathelicidin antimicrobial peptides (CAMP) LL-37 and FALL-39 are polypeptides that are primarily stored in the lysosomes of macrophages and polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs); in humans, the CAMP gene encodes the peptide precursor CAP-18 (18 kDa), which is processed by proteinase 3-mediated extracellular cleavage into the active forms LL-37 and FALL-39.[4][5]

Cathelicidins serve a critical role in mammalian innate immune defence against invasive bacterial infection.[6] The cathelicidin family of peptides are classified as antimicrobial peptides (AMPs). The AMP family also includes the defensins. Whilst the defensins share common structural features, cathelicidin-related peptides are highly heterogeneous.[6] Members of the cathelicidin family of antimicrobial polypeptides are characterized by a highly conserved region (cathelin domain) and a highly variable cathelicidin peptide domain.[6]

Cathelicidin peptides have been isolated from many different species of mammals. Cathelicidins are mostly found in neutrophils, monocytes, mast cells, dendritic cells and macrophages[7] after activation by bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites or the hormone 1,25-D, which is the hormonally active form of vitamin D.[8] They have been found in some other cells including epithelial cells and human keratinocytes.[9]

Mechanism of antimicrobial activity

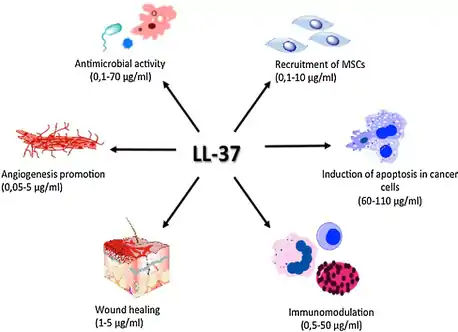

The general rule of the mechanism triggering cathelicidin action, like that of other antimicrobial peptides, involves the disintegration (damaging and puncturing) of cell membranes of organisms toward which the peptide is active.[10] Cathelicidin rapidly destroys the lipoprotein membranes of microbes enveloped in phagosomes after fusion with lysosomes in macrophages. Therefore, LL-37 can inhibit the formation of bacterial biofilms.[11]

Other activities

LL-37 plays role in the activation of cell proliferation and migration and it contributes to the wound closure process.[12] All these mechanisms together play an important role in tissue homeostasis and regenerative processes. Moreover, it has an agonistic effect on various pleiotropic receptors, for example, formyl peptide receptor like-1 (FPRL-1),[13] purinergic receptor P2X7, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)[14] or insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R).[15] These receptors play an important immunomodulatory role in, among other things, anti-tumor immune response.

Furthermore, it induces angiogenesis [16] and regulates apoptosis.[17] These processes are dysregulated during tumor development and thus LL-37 might be involved in pathogenesis of malignant tumors.

Characteristics

Cathelicidins range in size from 12 to 80 amino acid residues and have a wide range of structures.[18] Most cathelicidins are linear peptides with 23-37 amino acid residues, and fold into amphipathic α-helices. Additionally cathelicidins may also be small-sized molecules (12-18 residues) with beta-hairpin structures, stabilized by one or two disulphide bonds. Even larger cathelicidin peptides (39-80 amino acid residues) are also present. These larger cathelicidins display repetitive proline motifs forming extended polyproline-type structures.[6]

The cathelicidin family shares primary sequence homology with the cystatin[19] family of cysteine proteinase inhibitors, although amino acid residues thought to be important in such protease inhibition are usually lacking.

Non-human orthologs

Cathelicidin peptides have been found in humans, monkeys, mice, rats, rabbits, guinea pigs, pandas, pigs, cattle, frogs, sheep, goats, chickens, and horses. About 30 cathelicidin family members have been described in mammals.

Currently identified cathelicidin peptides include the following:[6]

- Human: hCAP-18 (cleaved into LL-37 and FALL-39)

- Rhesus monkey: RL-37

- Mice:CRAMP-1/2, (Cathelicidin-related Antimicrobial Peptide[20]

- Rats: rCRAMP

- Rabbits: CAP-18

- Guinea pig: CAP-11

- Pigs: PR-39, Prophenin, PMAP-23,36,37

- Cattle: BMAP-27,28,34 (Bovine Myeloid Antimicrobial Peptides); Bac5, Bac7

- Frogs: cathelicidin-AL (found in Amolops loloensis)[21]

- Chickens: Four cathelicidins, fowlicidins 1,2,3 and cathelicidin Beta-1 [22]

- Tasmanian Devil: Saha-CATH5 [23]

- Salmonids: CATH1 and CATH2

Clinical significance

Patients with rosacea have elevated levels of cathelicidin and elevated levels of stratum corneum tryptic enzymes (SCTEs). Cathelicidin is cleaved into the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 by both kallikrein 5 and kallikrein 7 serine proteases. Excessive production of LL-37 is suspected to be a contributing cause in all subtypes of Rosacea.[24] Antibiotics have been used in the past to treat rosacea, but antibiotics may only work because they inhibit some SCTEs.[25]

Higher plasma levels of human cathelicidin antimicrobial protein (hCAP18) appear to significantly reduce the risk of death from infection in dialysis patients. Patients with a high level of this protein were 3.7 times more likely to survive kidney dialysis for a year without a fatal infection.[26] The production of cathelicidin is up-regulated by Vitamin D.[27][28]

SAAP-148 (a synthetic antimicrobial and antibiofilm peptide) is a modified version of LL-37 that has enhanced antimicrobial activities compared to LL-37. In particular, SAAP-148 was more efficient in killing bacteria under physiological conditions.[29]

LL-37 is thought to play a role in psoriasis pathogenesis (along with other anti-microbial peptides). In psoriasis, damaged keratinocytes release LL-37 which forms complexes with self-genetic material (DNA or RNA) from other cells. These complexes stimulate dendritic cells (a type of antigen presenting cell) which then release interferon α and β which contributes to differentiation of T-cells and continued inflammation.[30] LL-37 has also been found to be a common auto-antigen in psoriasis; T-cells specific to LL-37 were found in the blood and skin in two thirds of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.[30]

References

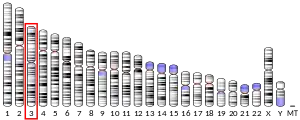

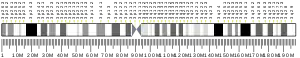

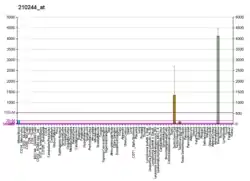

- GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000164047 - Ensembl, May 2017

- "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Entrez Gene: CAMP cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide".

- UniProt entry: P49913 Retrieved 29 November 2019

- Zanetti M (January 2004). "Cathelicidins, multifunctional peptides of the innate immunity". Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 75 (1): 39–48. doi:10.1189/jlb.0403147. PMID 12960280. S2CID 14902156.

- Vandamme D, Landuyt B, Luyten W, Schoofs L (November 2012). "A comprehensive summary of LL-37, the factotum human cathelicidin peptide". Cellular Immunology. 280 (1): 22–35. doi:10.1016/j.cellimm.2012.11.009. PMID 23246832.

- Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, Wenzel L, Tan BH, Krutzik SR, et al. (March 2006). "Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response". Science. 311 (5768): 1770–3. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1770L. doi:10.1126/science.1123933. PMID 16497887. S2CID 52869005.

- Bals R, Wang X, Zasloff M, Wilson JM (August 1998). "The peptide antibiotic LL-37/hCAP-18 is expressed in epithelia of the human lung where it has broad antimicrobial activity at the airway surface". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (16): 9541–6. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.9541B. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.16.9541. PMC 21374. PMID 9689116.

- Kościuczuk EM, Lisowski P, Jarczak J, Strzałkowska N, Jóźwik A, Horbańczuk J, et al. (December 2012). "Cathelicidins: family of antimicrobial peptides. A review". Molecular Biology Reports. 39 (12): 10957–70. doi:10.1007/s11033-012-1997-x. PMC 3487008. PMID 23065264.

- Dosler S, Karaaslan E (December 2014). "Inhibition and destruction of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms by antibiotics and antimicrobial peptides". Peptides. 62: 32–7. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2014.09.021. PMID 25285879. S2CID 207359996.

- Shaykhiev R, Beisswenger C, Kändler K, Senske J, Püchner A, Damm T, et al. (November 2005). "Human endogenous antibiotic LL-37 stimulates airway epithelial cell proliferation and wound closure". American Journal of Physiology. Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 289 (5): L842-8. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00286.2004. PMID 15964896.

- Chen Q, Schmidt AP, Anderson GM, Wang JM, Wooters J, Oppenheim JJ, Chertov O (October 2000). "LL-37, the neutrophil granule- and epithelial cell-derived cathelicidin, utilizes formyl peptide receptor-like 1 (FPRL1) as a receptor to chemoattract human peripheral blood neutrophils, monocytes, and T cells". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 192 (7): 1069–74. doi:10.1084/jem.192.7.1069. PMC 2193321. PMID 11015447.

- von Haussen J, Koczulla R, Shaykhiev R, Herr C, Pinkenburg O, Reimer D, et al. (January 2008). "The host defence peptide LL-37/hCAP-18 is a growth factor for lung cancer cells". Lung Cancer. 59 (1): 12–23. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.07.014. PMID 17764778.

- Girnita A, Zheng H, Grönberg A, Girnita L, Ståhle M (January 2012). "Identification of the cathelicidin peptide LL-37 as agonist for the type I insulin-like growth factor receptor". Oncogene. 31 (3): 352–65. doi:10.1038/onc.2011.239. PMC 3262900. PMID 21685939.

- Koczulla R, von Degenfeld G, Kupatt C, Krötz F, Zahler S, Gloe T, et al. (June 2003). "An angiogenic role for the human peptide antibiotic LL-37/hCAP-18". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 111 (11): 1665–72. doi:10.1172/JCI17545. PMC 156109. PMID 12782669.

- Ren SX, Shen J, Cheng AS, Lu L, Chan RL, Li ZJ, et al. (2013-05-20). Nie D (ed.). "FK-16 derived from the anticancer peptide LL-37 induces caspase-independent apoptosis and autophagic cell death in colon cancer cells". PLOS ONE. 8 (5): e63641. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...863641R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063641. PMC 3659029. PMID 23700428.

- Gennaro R, Zanetti M (2000). "Structural features and biological activities of the cathelicidin-derived antimicrobial peptides". Biopolymers. 55 (1): 31–49. doi:10.1002/1097-0282(2000)55:1<31::AID-BIP40>3.0.CO;2-9. PMID 10931440.

- Zaiou M, Nizet V, Gallo RL (May 2003). "Antimicrobial and protease inhibitory functions of the human cathelicidin (hCAP18/LL-37) prosequence". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 120 (5): 810–6. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12132.x. PMID 12713586.

- Gallo RL, Kim KJ, Bernfield M, Kozak CA, Zanetti M, Merluzzi L, Gennaro R (May 1997). "Identification of CRAMP, a cathelin-related antimicrobial peptide expressed in the embryonic and adult mouse". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (20): 13088–93. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.20.13088. PMID 9148921.

- Hao X, Yang H, Wei L, Yang S, Zhu W, Ma D, Yu H, Lai R (August 2012). "Amphibian cathelicidin fills the evolutionary gap of cathelicidin in vertebrate". Amino Acids. 43 (2): 677–85. doi:10.1007/s00726-011-1116-7. PMID 22009138. S2CID 2794908.

- Achanta M, Sunkara LT, Dai G, Bommineni YR, Jiang W, Zhang G (May 2012). "Tissue expression and developmental regulation of chicken cathelicidin antimicrobial peptides". Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology. 3 (1): 15. doi:10.1186/2049-1891-3-15. PMC 3436658. PMID 22958518.

- Peel E, Cheng Y, Djordjevic JT, Fox S, Sorrell TC, Belov K (October 2016). "Cathelicidins in the Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii)". Scientific Reports. 6: 35019. Bibcode:2016NatSR...635019P. doi:10.1038/srep35019. PMC 5057115. PMID 27725697.

- Reinholz M, Ruzicka T, Schauber J (May 2012). "Cathelicidin LL-37: an antimicrobial peptide with a role in inflammatory skin disease". Annals of Dermatology. 24 (2): 126–35. doi:10.5021/ad.2012.24.2.126. PMC 3346901. PMID 22577261.

- Yamasaki K, Di Nardo A, Bardan A, Murakami M, Ohtake T, Coda A, Dorschner RA, Bonnart C, Descargues P, Hovnanian A, Morhenn VB, Gallo RL (August 2007). "Increased serine protease activity and cathelicidin promotes skin inflammation in rosacea". Nature Medicine. 13 (8): 975–80. doi:10.1038/nm1616. PMID 17676051. S2CID 23470611.

- Gombart AF, Bhan I, Borregaard N, Tamez H, Camargo CA, Koeffler HP, Thadhani R (February 2009). "Low plasma level of cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (hCAP18) predicts increased infectious disease mortality in patients undergoing hemodialysis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 48 (4): 418–24. doi:10.1086/596314. PMC 6944311. PMID 19133797.

- Zasloff M (January 2002). "Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms". Nature. 415 (6870): 389–95. Bibcode:2002Natur.415..389Z. doi:10.1038/415389a. PMID 11807545. S2CID 205028607.

- Kamen DL, Tangpricha V (May 2010). "Vitamin D and molecular actions on the immune system: modulation of innate and autoimmunity". Journal of Molecular Medicine. 88 (5): 441–50. doi:10.1007/s00109-010-0590-9. PMC 2861286. PMID 20119827.

- de Breij A, Riool M, Cordfunke RA, Malanovic N, de Boer L, Koning RI, et al. (January 2018). "The antimicrobial peptide SAAP-148 combats drug-resistant bacteria and biofilms". Science Translational Medicine. 10 (423): eaan4044. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aan4044. PMID 29321257.

- Rendon A, Schäkel K (March 2019). "Psoriasis Pathogenesis and Treatment". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 20 (6): 1475. doi:10.3390/ijms20061475. PMC 6471628. PMID 30909615.

Further reading

- Dürr UH, Sudheendra US, Ramamoorthy A (September 2006). "LL-37, the only human member of the cathelicidin family of antimicrobial peptides". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 1758 (9): 1408–25. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.03.030. PMID 16716248.

- Chromek M, Slamová Z, Bergman P, Kovács L, Podracká L, Ehrén I, Hökfelt T, Gudmundsson GH, Gallo RL, Agerberth B, Brauner A (June 2006). "The antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin protects the urinary tract against invasive bacterial infection". Nature Medicine. 12 (6): 636–41. doi:10.1038/nm1407. PMID 16751768. S2CID 20704807.

- Gombart AF, Borregaard N, Koeffler HP (July 2005). "Human cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) gene is a direct target of the vitamin D receptor and is strongly up-regulated in myeloid cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3". FASEB Journal. 19 (9): 1067–77. doi:10.1096/fj.04-3284com. PMID 15985530. S2CID 7563259.

- López-García B, Lee PH, Gallo RL (May 2006). "Expression and potential function of cathelicidin antimicrobial peptides in dermatophytosis and tinea versicolor". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 57 (5): 877–82. doi:10.1093/jac/dkl078. PMID 16556635.

- Lehrer RI, Ganz T (January 2002). "Cathelicidins: a family of endogenous antimicrobial peptides". Current Opinion in Hematology. 9 (1): 18–22. doi:10.1097/00062752-200201000-00004. PMID 11753073. S2CID 23575052.

- Niyonsaba F, Hirata M, Ogawa H, Nagaoka I (September 2003). "Epithelial cell-derived antibacterial peptides human beta-defensins and cathelicidin: multifunctional activities on mast cells". Current Drug Targets. Inflammation and Allergy. 2 (3): 224–31. doi:10.2174/1568010033484115. PMID 14561157.

- van Wetering S, Tjabringa GS, Hiemstra PS (April 2005). "Interactions between neutrophil-derived antimicrobial peptides and airway epithelial cells". Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 77 (4): 444–50. doi:10.1189/jlb.0604367. PMID 15591123. S2CID 8261526.

- Agerberth B, Gunne H, Odeberg J, Kogner P, Boman HG, Gudmundsson GH (January 1995). "FALL-39, a putative human peptide antibiotic, is cysteine-free and expressed in bone marrow and testis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 92 (1): 195–9. Bibcode:1995PNAS...92..195A. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.1.195. PMC 42844. PMID 7529412.

- Cowland JB, Johnsen AH, Borregaard N (July 1995). "hCAP-18, a cathelin/pro-bactenecin-like protein of human neutrophil specific granules". FEBS Letters. 368 (1): 173–6. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(95)00634-L. PMID 7615076. S2CID 3172761.

- Gudmundsson GH, Magnusson KP, Chowdhary BP, Johansson M, Andersson L, Boman HG (July 1995). "Structure of the gene for porcine peptide antibiotic PR-39, a cathelin gene family member: comparative mapping of the locus for the human peptide antibiotic FALL-39". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 92 (15): 7085–9. Bibcode:1995PNAS...92.7085G. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.15.7085. PMC 41476. PMID 7624374.

- Larrick JW, Hirata M, Balint RF, Lee J, Zhong J, Wright SC (April 1995). "Human CAP18: a novel antimicrobial lipopolysaccharide-binding protein". Infection and Immunity. 63 (4): 1291–7. doi:10.1128/IAI.63.4.1291-1297.1995. PMC 173149. PMID 7890387.

- Gudmundsson GH, Agerberth B, Odeberg J, Bergman T, Olsson B, Salcedo R (June 1996). "The human gene FALL39 and processing of the cathelin precursor to the antibacterial peptide LL-37 in granulocytes". European Journal of Biochemistry. 238 (2): 325–32. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0325z.x. PMID 8681941.

- Larrick JW, Lee J, Ma S, Li X, Francke U, Wright SC, Balint RF (November 1996). "Structural, functional analysis and localization of the human CAP18 gene". FEBS Letters. 398 (1): 74–80. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(96)01199-4. PMID 8946956. S2CID 35329283.

- Frohm M, Agerberth B, Ahangari G, Stâhle-Bäckdahl M, Lidén S, Wigzell H, Gudmundsson GH (June 1997). "The expression of the gene coding for the antibacterial peptide LL-37 is induced in human keratinocytes during inflammatory disorders". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (24): 15258–63. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.24.15258. PMID 9182550.

- Bals R, Wang X, Zasloff M, Wilson JM (August 1998). "The peptide antibiotic LL-37/hCAP-18 is expressed in epithelia of the human lung where it has broad antimicrobial activity at the airway surface". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (16): 9541–6. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.9541B. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.16.9541. PMC 21374. PMID 9689116.

- Chen Q, Schmidt AP, Anderson GM, Wang JM, Wooters J, Oppenheim JJ, Chertov O (October 2000). "LL-37, the neutrophil granule- and epithelial cell-derived cathelicidin, utilizes formyl peptide receptor-like 1 (FPRL1) as a receptor to chemoattract human peripheral blood neutrophils, monocytes, and T cells". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 192 (7): 1069–74. doi:10.1084/jem.192.7.1069. PMC 2193321. PMID 11015447.

- Agerberth B, Charo J, Werr J, Olsson B, Idali F, Lindbom L, Kiessling R, Jörnvall H, Wigzell H, Gudmundsson GH (November 2000). "The human antimicrobial and chemotactic peptides LL-37 and alpha-defensins are expressed by specific lymphocyte and monocyte populations". Blood. 96 (9): 3086–93. doi:10.1182/blood.V96.9.3086. PMID 11049988.

- Bals R, Lang C, Weiner DJ, Vogelmeier C, Welsch U, Wilson JM (March 2001). "Rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) mucosal antimicrobial peptides are close homologues of human molecules". Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology. 8 (2): 370–5. doi:10.1128/CDLI.8.2.370-375.2001. PMC 96065. PMID 11238224.

- Nagaoka I, Hirota S, Niyonsaba F, Hirata M, Adachi Y, Tamura H, Heumann D (September 2001). "Cathelicidin family of antibacterial peptides CAP18 and CAP11 inhibit the expression of TNF-alpha by blocking the binding of LPS to CD14(+) cells". Journal of Immunology. 167 (6): 3329–38. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3329. PMID 11544322.

- Hase K, Eckmann L, Leopard JD, Varki N, Kagnoff MF (February 2002). "Cell differentiation is a key determinant of cathelicidin LL-37/human cationic antimicrobial protein 18 expression by human colon epithelium". Infection and Immunity. 70 (2): 953–63. doi:10.1128/IAI.70.2.953-963.2002. PMC 127717. PMID 11796631.

- Giuliani A, Pirri G, Nicoletto S (2007). "Antimicrobial peptides: an overview of a promising class of therapeutics". Cent. Eur. J. Biol. 2 (1): 1–33. doi:10.2478/s11535-007-0010-5.

- Burton MF, Steel PG (December 2009). "The chemistry and biology of LL-37". Natural Product Reports. 26 (12): 1572–84. doi:10.1039/b912533g. PMID 19936387.